Is the Administration Ignoring the Dangers of Training Libyan Pilots and Nuclear Scientists?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B6 Report During the Afternoon of March 3, Advisers to Muammar

UNCLASSIFIED STATE DEPT. - PRODUCED TO HOUSE SELECT BENGHAZI COMM. U.S. Department of State SUBJECT TO AGREEMENT ON SENSITIVE INFORMATION & REDACTIONS. NO FOIA WAIVER. Case No. F-2015-04841 Doc No. C05739546 Date: 05/13/2015 RELEASE IN PART B6 From: B6 Sent: Thursday, March 3, 2011 9:45 PM To: Subject: H: Latest How Syria is aiding Qaddafi and more... Sid Attachments: hrc memo syria aiding libya 030311.docx; hrc memo syria aiding libya 030311.docx CONFIDENTIAL March 3, 2011 For: Hillary From: Sid Re: Syria aiding Qaddafi This memo has two parts. Part one is the report that Syria is providing air support for Qaddafi. Part two is a note to Cody from Lord David Owen, former UK foreign secretary on his views of an increasingly complex crisis. It seems that the situation is developing into a protracted civil war with various nations backing opposing sides with unforeseen consequences. Under these circumstances the crucial challenge is to deprive Qaddafi of his strategic depth—his support both financial and military. I. Report During the afternoon of March 3, advisers to Muammar Qaddafi stated privately that the Libyan Leader has decided that civil war is inevitable, pitting troops and mercenary troops loyal to him against the rebel forces gathering around Benghazi. Qaddafi is convinced that these rebels are being supported by the United States, Western Europe and Israel. On March 2 Qaddafi told his son Saif al-Islam that he believes the intelligence services of the United States, Great Britain, Egypt, and France have deployed paramilitary officers to Benghazi to assist in organizing, training, and equipping opposition forces. -

World Air Forces Flight 2011/2012 International

SPECIAL REPORT WORLD AIR FORCES FLIGHT 2011/2012 INTERNATIONAL IN ASSOCIATION WITH Secure your availability. Rely on our performance. Aircraft availability on the flight line is more than ever essential for the Air Force mission fulfilment. Cooperating with the right industrial partner is of strategic importance and key to improving Air Force logistics and supply chain management. RUAG provides you with new options to resource your mission. More than 40 years of flight line management make us the experienced and capable partner we are – a partner you can rely on. RUAG Aviation Military Aviation · Seetalstrasse 175 · P.O. Box 301 · 6032 Emmen · Switzerland Legal domicile: RUAG Switzerland Ltd · Seetalstrasse 175 · P.O. Box 301 · 6032 Emmen Tel. +41 41 268 41 11 · Fax +41 41 260 25 88 · [email protected] · www.ruag.com WORLD AIR FORCES 2011/2012 CONTENT ANALYSIS 4 Worldwide active fleet per region 5 Worldwide active fleet share per country 6 Worldwide top 10 active aircraft types 8 WORLD AIR FORCES World Air Forces directory 9 TO FIND OUT MORE ABOUT FLIGHTGLOBAL INSIGHT AND REPORT SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES, CONTACT: Flightglobal Insight Quadrant House, The Quadrant Sutton, Surrey, SM2 5AS, UK Tel: + 44 208 652 8724 Email:LQVLJKW#ÁLJKWJOREDOFRP Website: ZZZÁLJKWJOREDOFRPLQVLJKt World Air Forces 2011/2012 | Flightglobal Insight | 3 WORLD AIR FORCES 2011/2012 The French and Qatari air forces deployed Mirage 2000-5s for the fight over Libya JOINT RESPONSE Air arms around the world reacted to multiple challenges during 2011, despite fleet and budget cuts. We list the current inventories and procurement plans of 160 nations. -

Operation Odyssey Dawn (Libya): Background and Issues for Congress

Operation Odyssey Dawn (Libya): Background and Issues for Congress Jeremiah Gertler, Coordinator Specialist in Military Aviation March 30, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41725 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Operation Odyssey Dawn (Libya): Background and Issues for Congress Summary This report provides an overview of military operations in Libya under U.S. command from March 19 to March 29, 2011, and the most recent developments with respect to the transfer of command of military operations from the United States to NATO on March 30. The ongoing uprising in Libya against the government of Muammar al Qadhafi has been the subject of evolving domestic and international debate about potential international military intervention, including the proposed establishment of a no-fly zone over Libya. On March 17, 2011, the United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 1973, establishing a no-fly zone in Libyan airspace, authorizing robust enforcement measures for the arms embargo established by Resolution 1970, and authorizing member states “to take all necessary measures … to protect civilians and civilian populated areas under threat of attack in the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, including Benghazi, while excluding a foreign occupation force of any form on any part of Libyan territory.” In response, the United States established Operation Odyssey Dawn, the U.S. contribution to a multilateral military effort to enforce a no-fly zone and protect civilians in Libya. Military operations under Odyssey Dawn commenced on March 19, 2011. U.S. and coalition forces quickly established command of the air over Libya’s major cities, destroying portions of the Libyan air defense network and attacking pro-Qadhafi forces deemed to pose a threat to civilian populations. -

The North African Military Balance Have Been Erratic at Best

CSIS _______________________________ Center for Strategic and International Studies 1800 K Street N.W. Washington, DC 20006 (202) 775 -3270 Access Web: ww.csis.org Contact the Author: [email protected] The No rth African Military Balance: Force Developments in the Maghreb Anthony H. Cordesman Center for Strategic and International Studies With the Assistance of Khalid Al -Rodhan Working Draft: Revised March 28, 2005 Please note that this documen t is a working draft and will be revised regularly. To comment, or to provide suggestions and corrections, please e - mail the author at [email protected] . Cordesman: The Middle East Military Ba lance: Force Development in North Africa 3/28/05 Page ii Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION ................................ ................................ ................................ ................................ .................... 5 RESOURCES AND FORCE TRENDS ................................ ................................ ................................ ............................... 5 II. NATIONAL MILITAR Y FORCES ................................ ................................ ................................ .................... 22 THE MILITARY FORCES OF MOROCCO ................................ ................................ ................................ ...................... 22 Moroccan Army ................................ ................................ ................................ ................................ ................... 22 Moroccan Navy ............................... -

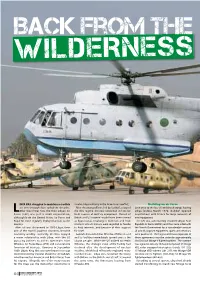

Back from the Wilderness Back from the Wilderness

Back from the Wilderness Back from the Wilderness IBYA HAS struggled to maintain a credible involve Libya militarily in the Arab-Israeli conflict. Building an air force air arm through four turbulent decades. After the young officers, led by Gaddafi, usurped Even prior to the last US and British troops leaving LAfter World War Two, the then Libyan Air the Idris regime, the new rulers had to look for Libya, before March 1970, Gaddafi opened Force (LAF) was just a small organisation, fresh sources of military equipment. Pursuit of negotiations with France for large amounts of although both the United States Air Force and British and US materiel would have been viewed new equipment. Royal Air Force regularly deployed aircraft to the as hypocritical, resulting in domestic and Arab The LAF was subsequently renamed Libyan Arab country. criticism as both nations were regarded as hostile Republic Air Force (LARAF), and then came a deal with After oil was discovered in 1959 Libya, then to Arab interests...and because of their support the French Government for a considerable amount one of the world’s poorest countries, became for Israel. of aircraft, support equipment, spares and weapons extremely wealthy. Generally, the West enjoyed Gaddafi demanded that Wheelus AFB be closed were purchased. The largest and most important of a warm relationship with Libya, with the US and its facilities immediately turned over to the these agreements was the order for approximately pursuing policies to aid its operations from Libyan people. While the US wished to retain 110 Dassault Mirage V fighter-bombers. -

Washington Watch by John A

Washington Watch By John A. Tirpak, Executive Editor March 19 dawns on Libya; Protecting our assets; Going offboard with the bomber. .... No Flies oN libya Washington, D.C., MarCh 21, 2011 The UN has implemented a no-fly zone over Libya, respond- ing to Muammar Qaddafi’s attempts put down a popular uprising by using mercenaries and air strikes on rebels and civilians alike. The March 17 authorization followed weeks of debate, DOD photo CHerieby Cullen during which it became clear that many US government and opinion leaders seemingly aren’t aware of the enormous com- mitment of resources such an operation requires. A no-fly zone is an aerial blockade that prevents a country from flying aircraft to attack its own citizens, and prevents weapons resupply by air. Such a military step was taken against Iraq after the first Gulf War in 1991—and persisted for nearly 12 years—and another was applied in the Balkans in the 1990s. The UN Security Council resolution demanded an immedi- ate cease-fire in Libya, a halt to all attacks on civilians, a halt Gortney: Targets included Qaddafi’s ground forces. of airlift of mercenaries into the ground fight, and authorized member states to use “all necessary measures” to enforce The attacks began on March 19. Air Force B-2 bombers the edict. It directed the establishment of “a ban on all flights struck Libyan Air Force hardened aircraft shelters while the in the airspace” of Libya to “help protect” civilians but granted Navy fired some 120 Tomahawk cruise missiles from ships safe passage to humanitarian flights. -

America's Secret Migs

THE UNITED STATES AIR FORCE SECRET COLD WAR TRAINING PROGRAM RED EAGLES America’s Secret MiGs STEVE DAVIES FOREWORD BY GENERAL J. JUMPER © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com RED EAGLES America’s Secret MiGs OSPREY PUBLISHING © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS DEDICATION 6 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 7 FOREWORD 10 INTRODUCTION 12 PART 1 ACQUIRING “THE ASSETS” 15 Chapter 1: HAVE MiGs, 1968–69 16 Chapter 2: A Genesis for the Red Eagles, 1972–77 21 PART 2 LAYING THE GROUND WORK 49 Chapter 3: CONSTANT PEG and Tonopah, 1977–79 50 Chapter 4: The Red Eagles’ First Days and the Early MiGs 78 Chapter 5: The “Flogger” Arrives, 1980 126 Chapter 6: Gold Wings, 1981 138 PART 3 EXPANDED EXPOSURES AND RED FLAG, 1982–85 155 Chapter 7: The Fatalists, 1982 156 Chapter 8: Postai’s Crash 176 Chapter 9: Exposing the TAF, 1983 193 Chapter 10: “The Air Force is Coming,” 1984 221 Chapter 11: From Black to Gray, 1985 256 PART 4 THE FINAL YEARS, 1986–88 275 Chapter 12: Increasing Blue Air Exposures, 1986 276 Chapter 13: “Red Country,” 1987 293 Chapter 14: Arrival Shows, 1988 318 POSTSCRIPT 327 ENDNOTES 330 APPENDICES 334 GLOSSARY 342 INDEX 346 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com DEDICATION In memory of LtCdr Hugh “Bandit” Brown and Capt Mark “Toast” Postai — 6 — © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This is a story about the Red Eagles: a group of men, and a handful of women, who provided America’s fighter pilots with a level of training that was the stuff of dreams. It was codenamed CONSTANT PEG. -

The Rise of Arab Air Power

26 November 2014 The Rise of Arab Air Power After decades of irrelevance, are the air forces of the Arab world on the mend? Florence Gaub has no doubts. The strategic threat posed by Iran has prompted a number of Arab states to overhaul and expand their air arms. By Florence Gaub for ISN When pictures of Mariam Al Mansouri – the first female fighter pilot in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) – traveled around the world in September, it symbolized the changing role of women in the Arab world and the collective fight against the Islamic state. But it also captured a new military phenomenon: after decades of strategic irrelevance, Arab air power is on the rise. In 2014, as Syria, Egypt, and Libya face strategic challenges for which their traditionally large air forces appear to be ill-suited, Gulf states such as Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Qatar have significantly expanded their aerial capabilities, largely as a means of balancing against Iran. Although building up air power makes sense, especially for small states like Qatar and the UAE, their task is now to ensure that it is deployed in tandem with other tools, rather than becoming a substitute for a broader strategy. A new balance of power in the air Until recently, Arab air forces played no role in the strategic landscape of the Middle East. Although Egypt and Syria had numerically strong fleets, neither had seen combat in three decades. Famously, both air forces were destroyed within a few hours by Israel during the Six Day War in 1967. -

Libya's Proxy Battlefield

Oxford Research Group | January 2015 Oxford Research Group Briefing – JANUARY 2014 LIBYA’S PROXY BATTLEFIELD Richard Reeve Summary Less than four years since NATO-led military intervention helped to unseat the 42-year Gaddafi dictatorship Libya is a failing state on the borders of Europe. Since last summer the country has been divided between two rival national governments and a series of sub-states controlled by loosely aligned tribal, militia and jihadist groups. Almost all European embassies have been evacuated and oil production has fallen by about 80% in response to the fighting. The rulers of Derna, a coastal city 300 km south of Crete, have declared their territory an exclave of the Islamic State. Jihadist groups based in Libya have raided into Tunisia, Algeria, Niger and Egypt and for almost a year controlled northern Mali. Hundreds of thousands of desperate African and Middle Eastern refugees and migrants are attempting to cross illegally into Italy, Malta and Greece from Libya’s coast. If the momentum seems to have been lost for consolidating the revolutionary transition, calls have inevitably risen for renewed foreign intervention to secure Libya and to protect its people and neighbours. The House of Representatives, elected in June 2014 by just 18% of eligible Libyans, retreated to Tobruk in far eastern Libya in August, issuing a call for UN intervention to protect civilians and institutions. This month it has refocused its appeals on the Cairo-based Arab League, which supports it against its Tripoli-based rivals. Speaking on behalf of Libya’s southern neighbours in the Sahel, Mali also appealed to the UN Security Council to intervene in Libya on 6 January. -

Libyan-American Relations, 1951-1959: the Decade of Weakness

LIBYAN-AMERICAN RELATIONS, 1951-1959: THE DECADE OF WEAKNESS by Hasan Karayam A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Public History Middle Tennessee State University December 2018 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Amy L. Sayward, Chair Dr. C. Brendan Martin Dr. Rebecca Conard Dr. Moses Tesi To the spirit of my pure mother who died while waiting for this moment. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study would not been possible without the support of my family, Sirte University, professors, Middle Tennessee State University (MTSU), and other institutions. First of all, I would like to express my deep gratitude to my parents for their unlimited support at all levels: to my mother, who died while encouraging and waiting on me for this moment, and to my father, who gave support to me to help me achieve my goals. Special thanks to my wife, who stood with me in every detail in this journey, who supported and encouraged me emotionally and psychologically. I must thank my university, Sirte University, which gave me a great opportunity by nominating me for a scholarship for a doctoral degree abroad so that I could return to enrich the university. Unfortunately, the events following the Arab Spring derailed our original plans, but my gratitude remains. My great gratitude goes to my dissertation committee members. I am in debt of acknowledgment to Dr. Amy Sayward for her invaluable support in every detail of my journey since the first meeting with her in May 2010 until this moment; thank you for your guidance, teaching, advice, full kindness, and sympathizing. -

Libya: Background and U.S

Libya: Background and U.S. Relations Christopher M. Blanchard Analyst in Middle Eastern Affairs August 3, 2009 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL33142 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Libya: Background and U.S. Relations Summary Libyan-U.S. rapprochement has unfolded gradually since 2003, when the Libyan government accepted responsibility for the actions of its personnel in regard to the 1988 bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 and announced its decision to eliminate its weapons of mass destruction and long- range missile programs. In response, U.S. sanctions were gradually removed, and, on May 15, 2006, the Bush Administration announced its intention to restore full diplomatic relations with Libya and to rescind Libya’s listing as a state sponsor of terrorism. Full diplomatic relations were restored on May 31, 2006 when the United States upgraded its Liaison Office in Tripoli to an Embassy. Libya was removed from the lists of state sponsors of terrorism and states not fully cooperating with U.S. counterterrorism efforts in June 2006. Until late 2008, U.S.-Libyan re-engagement was hindered by lingering disagreements over outstanding legal claims related to U.S. citizens killed or injured in past Libyan-sponsored or supported terrorist attacks. From 2004 onward, Bush Administration officials argued that broader normalization of U.S.-Libyan relations would provide opportunities for the United States to address specific issues of concern to Congress, including the outstanding legal claims, political and economic reform, the development of Libyan energy resources, and human rights. However, some Members of Congress took steps to limit U.S.-Libyan re-engagement as a means of encouraging the Libyan government to settle outstanding terrorism cases in good faith prior to further normalization. -

Air University Review: March-April 1975, Volume XXVI, No. 3

UNITED STATES AI R FORCE AIR UNIVERSITY Al R reviewU N I VE R S IT Y T H E PROFESSIONAl JOURNAL OF THE UNITED STATES AIR FORCE CONGRESS AND NATIONAL S E C U R IT Y ...................................................................................................................... * The Honorable William L. Dickinson, Member United States House of Representatives T he Dec isio n to Respond: W hat Forces Do We Need in a Crisis? .... 16 Lewis A. Frank COUNTERFORCE IN AN E r .A OF ESSENTIAL EQUIVALENCE......................................................... 27 Capt. D. J. Alberts, USAF N ew Waves in the South Atlantic: A S trategy Needed?............................................. 38 Dr. Richard E. Bissell Acquisition: A Dynamic Process...................................................................................................... 45 Lt. Col. David N. Burt. USAF Air Force Review T he New USAF F ighter Lead-In Program A Fir st Year’s Progress Report......................................................................................... 55 Lawrence R. Benson In My Opinion Program Management and Major Mo d if ic a t io n s ...................................................67 Lt. Col. George R. Hennigan, USAF C risis around the Air po r t ...................................................................................................... 75 Capt. John G. Terino, USAF Books and Ideas T he Metrics Are Coming! ............................................................................................................ 82 Dr. James