Libya's Proxy Battlefield

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B6 Report During the Afternoon of March 3, Advisers to Muammar

UNCLASSIFIED STATE DEPT. - PRODUCED TO HOUSE SELECT BENGHAZI COMM. U.S. Department of State SUBJECT TO AGREEMENT ON SENSITIVE INFORMATION & REDACTIONS. NO FOIA WAIVER. Case No. F-2015-04841 Doc No. C05739546 Date: 05/13/2015 RELEASE IN PART B6 From: B6 Sent: Thursday, March 3, 2011 9:45 PM To: Subject: H: Latest How Syria is aiding Qaddafi and more... Sid Attachments: hrc memo syria aiding libya 030311.docx; hrc memo syria aiding libya 030311.docx CONFIDENTIAL March 3, 2011 For: Hillary From: Sid Re: Syria aiding Qaddafi This memo has two parts. Part one is the report that Syria is providing air support for Qaddafi. Part two is a note to Cody from Lord David Owen, former UK foreign secretary on his views of an increasingly complex crisis. It seems that the situation is developing into a protracted civil war with various nations backing opposing sides with unforeseen consequences. Under these circumstances the crucial challenge is to deprive Qaddafi of his strategic depth—his support both financial and military. I. Report During the afternoon of March 3, advisers to Muammar Qaddafi stated privately that the Libyan Leader has decided that civil war is inevitable, pitting troops and mercenary troops loyal to him against the rebel forces gathering around Benghazi. Qaddafi is convinced that these rebels are being supported by the United States, Western Europe and Israel. On March 2 Qaddafi told his son Saif al-Islam that he believes the intelligence services of the United States, Great Britain, Egypt, and France have deployed paramilitary officers to Benghazi to assist in organizing, training, and equipping opposition forces. -

Analýza Zapojenia Zahraničných Aktérov V Kontexte Druhej Občianskej Vojny V Líbyi

FAKULTA SOCIÁLNÍCH STUDIÍ Analýza zapojenia zahraničných aktérov v kontexte druhej občianskej vojny v Líbyi Diplomová práca BC. TOMÁŠ MIČÍK Vedúci práce: Mgr. Josef Kraus, Ph.D. Katedra politologie odbor Bezpečnostní a strategická studia Brno 2021 Bibliografický záznam Autor: Bc. Tomáš Mičík Fakulta sociálních studií Masarykova univerzita Katedra politologie Název práce: Analýza zapojenia zahraničných aktérov v kontexte druhej občianskej vojny v Líbyi Studijní program: Bezpečnostní a strategická studia Studijní obor: Bezpečnostní a strategická studia Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Josef Kraus, Ph.D. Rok: 2021 Počet stran: 136 Klíčová slova: Líbya, líbyjská občianska vojna, Haftar, Sarraj, zahraniční aktéri, GNA, HoR, Arabská jar 2 Bibliographic record Author: Bc. Tomáš Mičík Faculty of Social Studies Masaryk University Department of Political Science Title of Thesis: Analysis of Foreign Actors‘ Involvement in the Context of Libyan Civil War Degree Programme: Security & Strategic Studies Field of Study: Security & Strategic Studies Supervisor: Mgr. Josef Kraus, Ph.D. Year: 2021 Number of Pages: 136 Keywords: Libya, Libyan civil war, Haftar, Sarraj, foreign actor, GNA, HoR, Arab spring 3 Abstrakt Tato diplomová práce se zabývá analýzou zahraničních aktérů v kontextu druhé občanské války v Libyi. Libye se v porevolučním období stala prostředím mocensko-politického, nábožensko-ideologického a ekonomického soupeření mnoha regionálních, evropských i globálních aktérů. Cílem této práce je podrobně zanalyzovat roli, zájmy, motivace a rozsah působení těchto zahraničních aktérů v rámci současně probíhající druhé libyjské občanské války. 4 Abstract This diploma thesis deals with the analysis of foreign actors in the context of the second civil war in Libya. In the post-revolutionary period, Libya became an environment of power-political, religious-ideological and economic rivalry between many regional, European and global actors. -

Of International Journal Euro-Mediterranean Studies

Euro-Mediterranean University Kidričevo nabrežje 2 SI-6330 Piran, Slovenia International Journal www.ijems.emuni.si [email protected] 1 of Euro-Mediterranean NUMBER Studies VOLUME 1 4 2021 NUMBER 1 2021 EDITORIAL A defining moment: Can we predict the future of higher education? Abdelhamid El-Zoheiry 14 SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE Security sector reform by intergovernmental organisations in Libya Anna Molnár, Ivett Szászi, Lili Takács VOLUME SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE Interpreting the Mediterranean archaeological landscape through stakeholders’ participation – the case of Vrsar, Croatia Kristina Afrić Rakitovac, Nataša Urošević, Nikola Vojnović REVIEW ARTICLE Olive oil tourism in the Euro-Mediterranean area José Manuel Hernández-Mogollón, Elide Di-Clemente, Ana María Campón-Cerro, José Antonio Folgado-Fernández SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE What ever happened to the EU’s ‘science diplomacy’? The long mission of effective EU-Mediterranean cooperation in science and research Jerneja Penca BOOK REVIEW Transnational Islam and regional security: Cooperation and diversity between Europe and North Africa, by Frédéric Volpi (ed.) Georgi Asatryan EVENT REVIEW Capacity building for healthy seas: Summer school on sustainable blue economy in the Euro-Mediterranean Jerneja Penca Abstracts Résumés Povzetki International Journal The International Journal of Euro- EdITOR-IN-CHIEF Advisory board of Euro-Mediterranean Studies Mediterranean Studies is published in Prof. Dr. Abdelhamid El-Zoheiry, Prof. Dr. Samia Kassab-Charfi, English with abstracts in Slovenian, ISSN 1855-3362 (printed) Euro-Mediterranean University, Slovenia University of Tunis, Tunisia French and Arabic language. The Prof. Dr. Abeer Refky, Arab Academy ISSN 2232-6022 (online) journal is free of charge. managing Editor: for Science, Technology and Maritime Transport, Egypt COPYRIGHT NOTICE Dr. -

World Air Forces Flight 2011/2012 International

SPECIAL REPORT WORLD AIR FORCES FLIGHT 2011/2012 INTERNATIONAL IN ASSOCIATION WITH Secure your availability. Rely on our performance. Aircraft availability on the flight line is more than ever essential for the Air Force mission fulfilment. Cooperating with the right industrial partner is of strategic importance and key to improving Air Force logistics and supply chain management. RUAG provides you with new options to resource your mission. More than 40 years of flight line management make us the experienced and capable partner we are – a partner you can rely on. RUAG Aviation Military Aviation · Seetalstrasse 175 · P.O. Box 301 · 6032 Emmen · Switzerland Legal domicile: RUAG Switzerland Ltd · Seetalstrasse 175 · P.O. Box 301 · 6032 Emmen Tel. +41 41 268 41 11 · Fax +41 41 260 25 88 · [email protected] · www.ruag.com WORLD AIR FORCES 2011/2012 CONTENT ANALYSIS 4 Worldwide active fleet per region 5 Worldwide active fleet share per country 6 Worldwide top 10 active aircraft types 8 WORLD AIR FORCES World Air Forces directory 9 TO FIND OUT MORE ABOUT FLIGHTGLOBAL INSIGHT AND REPORT SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES, CONTACT: Flightglobal Insight Quadrant House, The Quadrant Sutton, Surrey, SM2 5AS, UK Tel: + 44 208 652 8724 Email:LQVLJKW#ÁLJKWJOREDOFRP Website: ZZZÁLJKWJOREDOFRPLQVLJKt World Air Forces 2011/2012 | Flightglobal Insight | 3 WORLD AIR FORCES 2011/2012 The French and Qatari air forces deployed Mirage 2000-5s for the fight over Libya JOINT RESPONSE Air arms around the world reacted to multiple challenges during 2011, despite fleet and budget cuts. We list the current inventories and procurement plans of 160 nations. -

Operation Odyssey Dawn (Libya): Background and Issues for Congress

Operation Odyssey Dawn (Libya): Background and Issues for Congress Jeremiah Gertler, Coordinator Specialist in Military Aviation March 30, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41725 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Operation Odyssey Dawn (Libya): Background and Issues for Congress Summary This report provides an overview of military operations in Libya under U.S. command from March 19 to March 29, 2011, and the most recent developments with respect to the transfer of command of military operations from the United States to NATO on March 30. The ongoing uprising in Libya against the government of Muammar al Qadhafi has been the subject of evolving domestic and international debate about potential international military intervention, including the proposed establishment of a no-fly zone over Libya. On March 17, 2011, the United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 1973, establishing a no-fly zone in Libyan airspace, authorizing robust enforcement measures for the arms embargo established by Resolution 1970, and authorizing member states “to take all necessary measures … to protect civilians and civilian populated areas under threat of attack in the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, including Benghazi, while excluding a foreign occupation force of any form on any part of Libyan territory.” In response, the United States established Operation Odyssey Dawn, the U.S. contribution to a multilateral military effort to enforce a no-fly zone and protect civilians in Libya. Military operations under Odyssey Dawn commenced on March 19, 2011. U.S. and coalition forces quickly established command of the air over Libya’s major cities, destroying portions of the Libyan air defense network and attacking pro-Qadhafi forces deemed to pose a threat to civilian populations. -

Is the Administration Ignoring the Dangers of Training Libyan Pilots and Nuclear Scientists?

OVERTURNING 30 YEARS OF PRECEDENT: IS THE ADMINISTRATION IGNORING THE DANGERS OF TRAINING LIBYAN PILOTS AND NUCLEAR SCIENTISTS? JOINT HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON IMMIGRATION AND BORDER SECURITY OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY AND THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON NATIONAL SECURITY OF THE COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION APRIL 3, 2014 Serial No. 113–72 (Committee on the Judiciary) Serial No. 113–96 (Committee on Oversight and Government Reform) ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.fdsys.gov http://judiciary.house.gov http://www.house.gov/reform U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 87–425 PDF WASHINGTON : 2014 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY BOB GOODLATTE, Virginia, Chairman F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, JR., JOHN CONYERS, JR., Michigan Wisconsin JERROLD NADLER, New York HOWARD COBLE, North Carolina ROBERT C. ‘‘BOBBY’’ SCOTT, Virginia LAMAR SMITH, Texas ZOE LOFGREN, California STEVE CHABOT, Ohio SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas SPENCER BACHUS, Alabama STEVE COHEN, Tennessee DARRELL E. ISSA, California HENRY C. ‘‘HANK’’ JOHNSON, JR., J. RANDY FORBES, Virginia Georgia STEVE KING, Iowa PEDRO R. PIERLUISI, Puerto Rico TRENT FRANKS, Arizona JUDY CHU, California LOUIE GOHMERT, Texas TED DEUTCH, Florida JIM JORDAN, Ohio LUIS V. GUTIERREZ, Illinois TED POE, Texas KAREN BASS, California JASON CHAFFETZ, Utah CEDRIC RICHMOND, Louisiana TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania SUZAN DelBENE, Washington TREY GOWDY, South Carolina JOE GARCIA, Florida RAU´ L LABRADOR, Idaho HAKEEM JEFFRIES, New York BLAKE FARENTHOLD, Texas DAVID N. -

Origins of the Libyan Conflict and Options for Its Resolution

ORIGINS OF THE LIBYAN CONFLICT AND OPTIONS FOR ITS RESOLUTION JONATHAN M. WINER MAY 2019 POLICY PAPER 2019-12 CONTENTS * 1 INTRODUCTION * 4 HISTORICAL FACTORS * 7 PRIMARY DOMESTIC ACTORS * 10 PRIMARY FOREIGN ACTORS * 11 UNDERLYING CONDITIONS FUELING CONFLICT * 12 PRECIPITATING EVENTS LEADING TO OPEN CONFLICT * 12 MITIGATING FACTORS * 14 THE SKHIRAT PROCESS LEADING TO THE LPA * 15 POST-SKHIRAT BALANCE OF POWER * 18 MOVING BEYOND SKHIRAT: POLITICAL AGREEMENT OR STALLING FOR TIME? * 20 THE CURRENT CONFLICT * 22 PATHWAYS TO END CONFLICT SUMMARY After 42 years during which Muammar Gaddafi controlled all power in Libya, since the 2011 uprising, Libyans, fragmented by geography, tribe, ideology, and history, have resisted having anyone, foreigner or Libyan, telling them what to do. In the process, they have frustrated the efforts of outsiders to help them rebuild institutions at the national level, preferring instead to maintain control locally when they have it, often supported by foreign backers. Despite General Khalifa Hifter’s ongoing attempt in 2019 to conquer Tripoli by military force, Libya’s best chance for progress remains a unified international approach built on near complete alignment among international actors, supporting Libyans convening as a whole to address political, security, and economic issues at the same time. While the tracks can be separate, progress is required on all three for any of them to work in the long run. But first the country will need to find a way to pull back from the confrontation created by General Hifter. © The Middle East Institute The Middle East Institute 1319 18th Street NW Washington, D.C. -

The North African Military Balance Have Been Erratic at Best

CSIS _______________________________ Center for Strategic and International Studies 1800 K Street N.W. Washington, DC 20006 (202) 775 -3270 Access Web: ww.csis.org Contact the Author: [email protected] The No rth African Military Balance: Force Developments in the Maghreb Anthony H. Cordesman Center for Strategic and International Studies With the Assistance of Khalid Al -Rodhan Working Draft: Revised March 28, 2005 Please note that this documen t is a working draft and will be revised regularly. To comment, or to provide suggestions and corrections, please e - mail the author at [email protected] . Cordesman: The Middle East Military Ba lance: Force Development in North Africa 3/28/05 Page ii Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION ................................ ................................ ................................ ................................ .................... 5 RESOURCES AND FORCE TRENDS ................................ ................................ ................................ ............................... 5 II. NATIONAL MILITAR Y FORCES ................................ ................................ ................................ .................... 22 THE MILITARY FORCES OF MOROCCO ................................ ................................ ................................ ...................... 22 Moroccan Army ................................ ................................ ................................ ................................ ................... 22 Moroccan Navy ............................... -

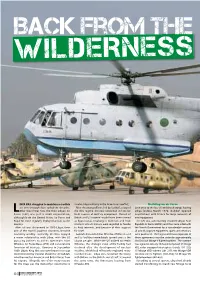

Back from the Wilderness Back from the Wilderness

Back from the Wilderness Back from the Wilderness IBYA HAS struggled to maintain a credible involve Libya militarily in the Arab-Israeli conflict. Building an air force air arm through four turbulent decades. After the young officers, led by Gaddafi, usurped Even prior to the last US and British troops leaving LAfter World War Two, the then Libyan Air the Idris regime, the new rulers had to look for Libya, before March 1970, Gaddafi opened Force (LAF) was just a small organisation, fresh sources of military equipment. Pursuit of negotiations with France for large amounts of although both the United States Air Force and British and US materiel would have been viewed new equipment. Royal Air Force regularly deployed aircraft to the as hypocritical, resulting in domestic and Arab The LAF was subsequently renamed Libyan Arab country. criticism as both nations were regarded as hostile Republic Air Force (LARAF), and then came a deal with After oil was discovered in 1959 Libya, then to Arab interests...and because of their support the French Government for a considerable amount one of the world’s poorest countries, became for Israel. of aircraft, support equipment, spares and weapons extremely wealthy. Generally, the West enjoyed Gaddafi demanded that Wheelus AFB be closed were purchased. The largest and most important of a warm relationship with Libya, with the US and its facilities immediately turned over to the these agreements was the order for approximately pursuing policies to aid its operations from Libyan people. While the US wished to retain 110 Dassault Mirage V fighter-bombers. -

Washington Watch by John A

Washington Watch By John A. Tirpak, Executive Editor March 19 dawns on Libya; Protecting our assets; Going offboard with the bomber. .... No Flies oN libya Washington, D.C., MarCh 21, 2011 The UN has implemented a no-fly zone over Libya, respond- ing to Muammar Qaddafi’s attempts put down a popular uprising by using mercenaries and air strikes on rebels and civilians alike. The March 17 authorization followed weeks of debate, DOD photo CHerieby Cullen during which it became clear that many US government and opinion leaders seemingly aren’t aware of the enormous com- mitment of resources such an operation requires. A no-fly zone is an aerial blockade that prevents a country from flying aircraft to attack its own citizens, and prevents weapons resupply by air. Such a military step was taken against Iraq after the first Gulf War in 1991—and persisted for nearly 12 years—and another was applied in the Balkans in the 1990s. The UN Security Council resolution demanded an immedi- ate cease-fire in Libya, a halt to all attacks on civilians, a halt Gortney: Targets included Qaddafi’s ground forces. of airlift of mercenaries into the ground fight, and authorized member states to use “all necessary measures” to enforce The attacks began on March 19. Air Force B-2 bombers the edict. It directed the establishment of “a ban on all flights struck Libyan Air Force hardened aircraft shelters while the in the airspace” of Libya to “help protect” civilians but granted Navy fired some 120 Tomahawk cruise missiles from ships safe passage to humanitarian flights. -

How Sirte Became a Hotbed of the Libyan Conflict Sirte: a New Frontline (June 2020) Cover

How Sirte Became a Hotbed of Issue 2021/05 the Libyan Conflict February 2021 Omar Al-Hawari1 Abstract The birthplace and former stronghold of the late Muammar Qadhafi, the coastal city of Sirte, was stigmatised and marginalised following the fall of the regime in October 2011. However, since 2019 it has again become the epicentre of Libya’s domestic and international conflict. How can this sudden change in the strategic importance of the city be explained? Based on numerous interviews with key actors from Sirte and on both warring sides, this paper analyses how the strategic importance of Sirte has evolved since Haftar’s LAAF military offensive on Tripoli in April 2019 and how the city has now become central to the Libyan conflict and its resolution through international diplomatic efforts. Introduction The city of Sirte, located in the middle of the Libyan littoral and at the western edge of the ‘Oil Crescent,’ was the theatre of the final battle of the 2011 civil war, but after being ‘liberated’ by the revolutionary forces in October it faded into the margins of Libya’s transition. The city was military defeated, socially marginalised and politically excluded. However, since 2019 it has again become the epicentre of Libya’s domestic and international conflict. How can this sudden BRIEF change in the strategic importance of the city be explained? The birthplace and former stronghold of the late Muammar Qadhafi, Sirte, and its inhabitants were marginalised and stigmatised following the fall of the regime in October 2011. Left devastated after weeks of shelling and street fighting, the city was still regarded by the new authorities as a stronghold of former regime supporters and the symbol of the ‘defeated’ in the civil war. -

America's Secret Migs

THE UNITED STATES AIR FORCE SECRET COLD WAR TRAINING PROGRAM RED EAGLES America’s Secret MiGs STEVE DAVIES FOREWORD BY GENERAL J. JUMPER © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com RED EAGLES America’s Secret MiGs OSPREY PUBLISHING © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS DEDICATION 6 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 7 FOREWORD 10 INTRODUCTION 12 PART 1 ACQUIRING “THE ASSETS” 15 Chapter 1: HAVE MiGs, 1968–69 16 Chapter 2: A Genesis for the Red Eagles, 1972–77 21 PART 2 LAYING THE GROUND WORK 49 Chapter 3: CONSTANT PEG and Tonopah, 1977–79 50 Chapter 4: The Red Eagles’ First Days and the Early MiGs 78 Chapter 5: The “Flogger” Arrives, 1980 126 Chapter 6: Gold Wings, 1981 138 PART 3 EXPANDED EXPOSURES AND RED FLAG, 1982–85 155 Chapter 7: The Fatalists, 1982 156 Chapter 8: Postai’s Crash 176 Chapter 9: Exposing the TAF, 1983 193 Chapter 10: “The Air Force is Coming,” 1984 221 Chapter 11: From Black to Gray, 1985 256 PART 4 THE FINAL YEARS, 1986–88 275 Chapter 12: Increasing Blue Air Exposures, 1986 276 Chapter 13: “Red Country,” 1987 293 Chapter 14: Arrival Shows, 1988 318 POSTSCRIPT 327 ENDNOTES 330 APPENDICES 334 GLOSSARY 342 INDEX 346 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com DEDICATION In memory of LtCdr Hugh “Bandit” Brown and Capt Mark “Toast” Postai — 6 — © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This is a story about the Red Eagles: a group of men, and a handful of women, who provided America’s fighter pilots with a level of training that was the stuff of dreams. It was codenamed CONSTANT PEG.