DUO Complete Version of Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An International Journal of English Studies 25/1 2016 EDITOR Prof

ANGLICA An International Journal of English Studies 25/1 2016 EDITOR prof. dr hab. Grażyna Bystydzieńska [[email protected]] ASSOCIATE EDITORS dr hab. Marzena Sokołowska-Paryż [[email protected]] dr Anna Wojtyś [[email protected]] ASSISTANT EDITORS dr Katarzyna Kociołek [[email protected]] dr Magdalena Kizeweter [[email protected]] ADVISORY BOARD GUEST REVIEWERS Michael Bilynsky, University of Lviv Dorota Babilas, University of Warsaw Andrzej Bogusławski, University of Warsaw Teresa Bela, Jagiellonian University, Cracow Mirosława Buchholtz, Nicolaus Copernicus University, Toruń Maria Błaszkiewicz, University of Warsaw Xavier Dekeyser University of Antwerp / KU Leuven Anna Branach-Kallas, Nicolaus Copernicus University, Toruń Bernhard Diensberg, University of Bonn Teresa Bruś, University of Wrocław, Poland Edwin Duncan, Towson University, Towson, MD Francesca de Lucia, independent scholar Jacek Fabiszak, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań Ilona Dobosiewicz, Opole University Jacek Fisiak, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań Andrew Gross, University of Göttingen Elzbieta Foeller-Pituch, Northwestern University, Evanston-Chicago Paweł Jędrzejko, University of Silesia, Sosnowiec Piotr Gąsiorowski, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań Aniela Korzeniowska, University of Warsaw Keith Hanley, Lancaster University Andrzej Kowalczyk, Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, Lublin Christopher Knight, University of Montana, Missoula, MT Barbara Kowalik, University of Warsaw Marcin Krygier, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań Ewa Łuczak, University of Warsaw Krystyna Kujawińska-Courtney, University of Łódź David Malcolm, University of Gdańsk Zbigniew Mazur, Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, Lublin Dominika Oramus University of Warsaw Znak ogólnodostępnyRafał / Molencki,wersje University językowe of Silesia, Sosnowiec Marek Paryż, University of Warsaw John G. Newman, University of Texas at Brownsville Anna Pochmara, University of Warsaw Michal Jan Rozbicki, St. -

The New Selection for Oprah's Book Club 2.0! RUBY a Novel by Cynthia Bond

The New Selection for Oprah’s Book Club 2.0! RUBY A Novel By Cynthia Bond Select Praise for RUBY “Bond proves to be a powerful literary force, a writer whose unflinching yet lyrical prose is reminiscent of Toni Morrison’s.” —O, The Oprah Magazine “Channeling the lyrical phantasmagoria of early Toni Morrison and the sexual and racial brutality of the 20th century east Texas, Cynthia Bond has created a moving and indelible portrait of a fallen woman ... Bond traffics in extremely difficult subjects with a grace and bigheartedness that makes for an accomplished, enthralling read.” —San Francisco Chronicle “In Ruby, Bond has created a heroine worthy of the great female protagonists of Toni Morrison … and Zora Neale Hurston … Bond’s style of writing is as magical as an East Texas sunrise, with phrases so deftly carved, the reader is often distracted from the brutality described by the sheer beauty of the language.” —Dallas Morning News An Indie Next Pick, Barnes & Noble “Discover Great New Writers” Selection, Library Journal “Breakout Literary Fiction” Pick, and a Southern Living Book Club Selection! In describing her debut novel, RUBY (Hogarth; February 10, 2015), Cynthia Bond has said “there are moments, spices, that have been stirred in slowly—from my life and from the stories of others.” She has drawn upon her own experiences, her family’s history, and the heartbreaking tales she’s heard through the years working with homeless and at-risk youth, including the brutal devastation of human trafficking, and woven these threads together to create a story that is truly unforgettable. -

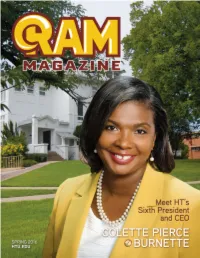

Vision a Connected World Where Diversity of Thought Matters

Mission HT nurtures a legacy of leadership and excellence in education, connecting knowledge, power, passion, and values. Vision A connected world where diversity of thought matters. Accreditation Huston-Tillotson University is accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges to award associate, baccalaureate and masters degrees. Contact the Commission on Colleges at 1866 Southern Lane, Decatur, Georgia 30033-4097 or call 404-679-4500 for questions about the accreditation of Huston-Tillotson University. From the President Everyday presents new opportunities to tell the world about this historic jewel in the heart of Austin, Texas— Huston-Tillotson University. I have met extraordinary students, passionate faculty and staff, proud alumni, and supportive community leaders. Thank you for making my transition a smooth one. was particularly moved by the motto that the leaders of the Samuel Huston College and Tillotson College crafted after merging the two institutions into one: In Union, Strength! These words are a testament to the hopefulness that the Ileaders envisioned. HT flourishes as a result of the combined strength of those who hold it dear, and I am proud to be a part of this great legacy. This edition of the Ram Magazine highlights the progress of the University and promotes the successes of faculty and students. It is the culminating work of President Emeritus Dr. Larry L. Earvin. I recognize the plateau of this labor of devotion to HT as my platform to continue moving the University forward. His culminating work is my platform to continue the progress of HT. As you read through these pages, take a minute to note many HT accomplishments. -

Art, Artist, and Witness(Ing) in Canada's Truth and Reconciliation

Dance with us as you can…: Art, Artist, and Witness(ing) in Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Journey by Jonathan Robert Dewar A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Indigenous and Canadian Studies Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2017, Jonathan Robert Dewar Abstract This dissertation explores, through in-depth interviews, the perspectives of artists and curators with regard to the question of the roles of art and artist – and the themes of community, responsibility, and practice – in truth, healing, and reconciliation during the early through late stages of the 2008-2015 mandate of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC), as its National Events, statement taking, and other programming began to play out across the country. The author presents the findings from these interviews alongside observations drawn from the unique positioning afforded to him through his professional work in healing and reconciliation-focused education and research roles at the Aboriginal Healing Foundation (2007-2012) and the Shingwauk Residential Schools Centre (2012-2016) about the ways art and artists were invoked and involved in the work of the TRC, alongside it, and/or in response to it. A chapter exploring Indigenous writing and reconciliation, with reference to the work of Basil Johnston, Jeannette Armstrong, Tomson Highway, Maria Campbell, Richard Wagamese, and many others, leads into three additional case studies. The first explores the challenges of exhibiting the legacies of Residential Schools, focusing on Jeff Thomas’ seminal curatorial work on the archival photograph-based exhibition Where Are the Children? Healing the Legacy of Residential Schools and Heather Igloliorte’s curatorial work on the exhibition ‘We were so far away…’: The Inuit Experience of Residential Schools, itself a response to feedback on Where Are the Children? Both examinations draw extensively from the author’s interviews with the curators. -

Making a Way out of No Way: Zora

ABSTRACT “‘Making a Way Out of No Way’: Zora Neale Hurston’s Hidden Discourse of Resistance” explores how Hurston used techniques she derived from the trickster tradition of African American folk culture in her narratives in order to resist and undermine the racism of the dominant discourse found in popular literature published during her lifetime. Critics have condemned her perceived willingness to use racist stereotypes in her work in order to pander to a white reading audience. This project asserts that Hurston did, indeed, don a “mask of minstrelsy” to play into her reading public’s often racist expectations in order to succeed as an academic and as a creative writer. At the same time, however, she crafted her narratives in a way that destabilized those expectations through use of sometimes subtle and sometimes blatant points of resistance. In this way, she was able to participate in a system that was rigged against her, as a woman and as an African American, by playing into the expectations of her audiences for economic and professional advantages while simultaneously undermining aspects of those expectations through rhetorical “winks,” exaggeration, sarcasm, and other forms of humor that enabled her to stay true to her personal values. While other scholars have examined Hurston’s discourse of resistance, this project takes a different approach by placing Hurston’s material in relation to the publishing climate at the time. Chapter One examines Mules and Men in the context of the revisions Hurston made to her scholarly work to transform her collection of folktales into a cohesive book marketed to a popular reading audience. -

Thomas Harris Cold Mountain

Revenge of the Radioactive Lady- Invisible City - Julia Dahl Elizabeth Stuckey-French The Wicked Girls - Alex Marwood The Spellman Files-Lisa Lutz Bridget Jones’s Diary - Afterwards - Rosamund Lupton Helen Fielding Ellen Foster - Kaye Gibbons Once Upon a River - Bonnie Jo Campbell The Devil She Knows - Demolition Angel - Robert Crais Bill Loehfelm Me Before You - Jojo Moyes The Sweetness at the Bottom of The Silence of the Lambs - the Pie - Alan Bradley Before I Go to Sleep - Thomas Harris S.J. Watson In the Woods - Tana French Cold Mountain - Charles Frazier Maya’s Notebook - The Likeness - Tana French Isabel Allende The Outlander - Gil Adamson These is My Words - Ruby - Cynthia Bond Winter’s Bone - Daniel Woodrell Nancy E. Turner The Untold - Courtney Collins Where'd You Go, Bernadette - A Tree Grows in Brooklyn - Maria Semple Betty Smith Lucky Us - Amy Bloom One Kick - Chelsea Cain Rebecca - Daphne du Maurier Falling From Horses - Molly Gloss Longbourn - Jo Baker Bury Me Deep - Megan Abbott The Silver Star - Sharp Objects - Gillian Flynn The Fever - Megan Abbott Jeannette Walls The Joy Luck Club - Amy Tan Beloved - Toni Morrison The Perfect Ghost - Linda Barnes Remarkable Creatures - Prayers for Sale - Sandra Dallas Tracy Chevalier The Midwife’s Tale - Shanghai Girls - Lisa See Samuel Thomas The Boston Girl - The Siege Winter - Anita Diamant Ariana Franklin Leaving Berlin The Son by Joseph Kanon by Philipp Meyer An atmospheric novel of postwar East Berlin, a Eli McCullough is kidnapped at age 13 by city caught between political idealism and the Comanches, and from then on his life becomes a harsh realities of Soviet occupation. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Representations of Transnational Violence

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Representations of Transnational Violence: Children in Contemporary Latin American Film, Literature, and Drawings A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Hispanic Languages and Literatures by Cheri Marie Robinson 2017 © Copyright by Cheri Marie Robinson 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Representations of Transnational Violence: Children in Contemporary Latin American Film, Literature, and Drawings by Cheri Marie Robinson Doctor of Philosophy in Hispanic Languages and Literatures University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor Adriana J. Bergero, Chair In this study, I examine representational strategies revolving around extreme violence and child/adolescent protagonists in films, literature, children’s drawings, and legal/political discourses in contemporary Latin American culture from an interdisciplinary approach. I analyze the mobilizing potential and uses of representations of child protagonists affected by violence and the cultures of impunity that facilitate its circulation. Within the works selected, I explore ways in which children can become sites of memory and justice through acts of witnessing, empathy, and the universal claim of natural law, with a primary focus on transnational and multidirectional depictions of violence (i.e. a violence in circulation) in extra-juridical, politicized, or aberrant environments in Latin American works. The historical periods contextualizing this study include the Argentine military dictatorship (1976-1983) and its interconnectedness to the violence of WWII and the Holocaust in Reina Roffé’s “La noche en blanco” (Chapter 1), the impact of ii transnational trajectories of genocidal violence in Argentine South Patagonia in 1959-1960 as depicted by Lucía Puenzo’s novel Wakolda (Chapter 2), Argentina’s transition to democracy (1990s) and the critical questions it raised regarding appropriated children and amnesty/justice in Dir. -

Spring 2015 a P U B L I C a T I O N O F T H E a M E R I C a N S O C I E T Y O F M a R I N E a R T I S T S

American Society of Marine Artists Spring 2015 A P u b l i c A t i o n o f t h e A m e r i c A n S o c i e t y o f m A r i n e A r t i S t S DeDicAteD to the Promotion of AmericAn mArine Art AnD the free exchAnge of iDeAS between ArtiStS Visit our Web Site at: www.americansocietyofmarineartists.com From The President Russ Kramer A Word About The American Society of Mystic, CT Marine Artists The American Society of Marine Artists is a non-profit organization whose purpose is to recognize and promote marine art and maritime Recently I had the opportunity - and honor - to speak to history. We seek to encourage cooperation a large group of folks gathered for a ‘Day of Learning’ at among artists, historians, marine enthusiasts the New Britain (Connecticut) Museum of American Art. and others engaged in activities relating to The museum is a treasure; it can trace its roots to 1853, and marine art and maritime history. Since its founding in 1978, the Society has brought over the ensuing century-and-a-half grew into one of the together some of America’s most talented most prestigious institutions featuring works by our nation’s artists. With contemporary artists in the marine art field. an impressive survey of the Hudson River School (Copley, Church, Cole), ✺ to Regionalism (O’Keeffe, Benton) to American Impressionism (Cassatt, Chase, Hassam) there is something to delight everyone. There’s also a great FELLOWS OF THE SOCIETY illustration collection, complete with a personal favorite of mine, a large Managing Fellow original canvas by N.C. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Ruby by Cynthia Bond Ruby by Cynthia Bond Review – a Survivor's Story of Love, Madness and Satanism

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Ruby by Cynthia Bond Ruby by Cynthia Bond review – a survivor's story of love, madness and Satanism. “H ell, ain’t nothing strange when Colored go crazy. Strange is when we don’t,” remarks a character in Cynthia Bond’s new novel, Ruby. And yet the people of Liberty Township in east Texas attribute the “howling, half-naked” madness of the title character to her own sins and travels, both a comeuppance for her preternatural beauty and an active choice. The locals never for a second stop to consider that Ruby Bell, the haunted, fatherless child of a light-skinned, red-haired woman, might have been shaped by the grinding weight of history. As Bond constructs that history over the 330 pages, we feel just how heavy it is. Before Ruby is even born, her aunt is shot and killed by the sheriff’s deputies for relenting to a married white man’s demands. As soon as Ruby is born, Ruby’s mother leaves her caramel-skinned baby girl and flees the rapes and ropes of the south to reinvent herself as a white woman in New York City. As a young child, with no adult protectors and only her friend Maggie to watch over her, Ruby is sent away and made to do horrifying things for pocket change. She keeps her lips numb and her eyes empty. Ruby by Cynthia Bond. In 1950, Ruby makes her escape to New York, “where Colored girls and White pretended to be equal”, to look for her mother. -

The Monstrous in Shakespeare by Patricia Richardson

The Monstrous in Shakespeare by Patricia Richardson A Thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the Degree of Master of Letters The Shakespeare Institute School of English The University of Birmingham June 2003 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Acknowledgements My thanks are due to John Jowett and Russell Jackson of the Shakespeare Institute for their advice, guidance and always-constructive criticism. I am also deeply indebted to Victoria Stec, Pat O'Neill and Hazell Bedell for all their help, support and encouragement. Any remaining errors, omissions and other weaknesses are entirely my own. Abstract This thesis argues that the view of human nature which emerges from Shakespeare's plays is essentially hybrid, protean and metamorphic. Chapter I discusses various early modem theories of the self and subsequent chapters explore the transforming power of love, twins and other doubles, transvestite heroines, the relationship between actor and role and the various forms of the monstrous in The Tempest. The plays considered include early, middle and late works and examples of comedy, tragedy, history and romance. -

Appendix Viii | 501

APPENDIX VIII | 501 APPENDIX VIII: TEXTS ASSIGNED, 2007/2008–2017/2018 Text Assignments "Introduction" and "Welcome to Crisis Ministry" 1 from Scratch Beginnings: Me, $25, and the Search for the American Dream (2008) / Adam W. Shepard "Lisa and American Anti-Intellectualism" from 1 The Simpsons and Philosophy: The D'oh! of Homer (2001) / Aeon J. Skoble "Only Connect…" The Goals of a Liberal 2 Education (1998) / William Cronan "What Is Service Learning?" from Learning 1 through Serving: A Student Guidebook for Service-Learning Across the Disciplines (2013) / Christine M. Cress $2.00 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in 2 America (2015) / H. Luke Shaefer and Kathryn Edin “They Say, I Say": The Moves That Matter in 1 Academic Writing (Third Edition) (2014) / Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein “Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in 4 the Cafeteria?” and Other Conversations About Race (1997) / Beverly Daniel Tatum 1 Dead in Attic: After Katrina (2007) / 3 Chris Rose 1000 Dollars and an Idea: Entrepreneur to 1 Billionaire (2009) / Sam Wyly 127 Hours Between a Rock and a Hard Place 1 (2004) / Aron Ralston 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before 2 Columbus (2005) / Charles Mann 1984 (1949) / George Orwell 2 29 Gifts: How a Month of Giving Can Change 1 Your Life (2009) / Cami Walker 31 Hours (2009) / Masha Hamilton 1 365 Days, 365 Plays (2006) / Suzan-Lori Parks 1 420 Characters (2011) / Lou Beach 1 A Backpack, a Bear, and Eight Crates of Vodka 2 (2014) / Lev Golinkin 502 | TEXTS ASSIGNED, 2007/2008–2017/2018 Text Assignments A Call to Action: Women, Religion, Violence, and 1 Power (2014) / Jimmy Carter A Chance in the World: An Orphan Boy, A 3 Mysterious Past, and How He Found a Place Called Home (2012) / Steve Pemberton A Chant to Soothe Wild Elephants (2008) / 2 Jaed Coffin A Companion for Owls: Being the Commonplace 1 Book of D. -

C:\Dokumente Und Einstellungen\Besitzer\Eigene

Allerliebst Lieber Klaus Schulze! Schreiben wollte ich Ihnen schon lange...jetzt bin ich seit drei Monaten wieder online TTHEHE KSKS CCIRCLEIRCLE und...hier ist meine kleine Story: Im Jahre 1980, Sie hatten dieses Auftragswerk in Linz, hatte ich einen Job als Sicherheitsorgan im Linzer Brucknerhaus. Auf Grund der mir selber auferlegten 16th Year April! April! 2011 Issue no. 170 lockeren Arbeitsdisziplin genehmigte ich mir einen nervenschonenden Schlaf so zwischen ein und vier Uhr nachts, ausgeführt auf den hierfür wunderbar geeigneten weichen Bänken des Foyers. In der nämlichen Nacht wurde ich in einer nie vergessenen Weise geweckt: von den mystisch-sphärischen Synth-Klängen von Ihnen Bom dia! Bonjour. ¡Buenos días! Ciao! Dag! Dzie ½ Dobry. Hei. Hello. Ola. Privet! im großen Saal des Brucknerhauses! Diese Stimmung... das abgedunkelte ΓΣΙά σας . Servus & Guten Tag. Brucknerhaus... verschlafen-übernächtig... Ihre Musik... dies alles hat sich unauslöschlich eingebrannt! Zudem war ich ja schon jahrelang Fan der elektronischen Musik und selbst auch Freizeitmusiker in div. Bands. Also, das ging N ATIONALITY ? echt tief und ich erinnere mich nach nunmehr über dreißig Jahren noch gerne daran, Hi Klaus, vor allem, wenn ich Ihre Musik mir zu Gemüte führe, die ich bis heute auch aktuell verfolge (Großartig das Konzert in der Loreley und Big in Japan). Thank you for your time in reading this e-mail question. Sehr geehrter Herr Klaus Schulze, abschließend ein spätes Dankeschön für I've been a long time fan of Klaus Schulze and German electronica since the mid 70s. dieses geschilderte inspirierende nächtliche Erlebnis und ich verbleibe in der and would like to ask your opinion as to why electronic music found such fertile Hoffnung, daß Ihre Gesundheit noch so manchen kreativen Output zuläßt..