Contemporary Queer Theatre As Utopic Activism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

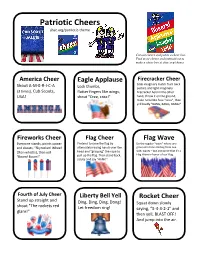

Patriotic Cheers Shac.Org/Patriotic-Theme

Patriotic Cheers shac.org/patriotic-theme Cut out cheers and put in a cheer box. Find more cheers and instructions to make a cheer box at shac.org/cheers. America Cheer Eagle Applause Firecracker Cheer Shout A-M-E-R-I-C-A Grab imaginary match from back Lock thumbs, pocket, and light imaginary (3 times), Cub Scouts, flutter fingers like wings, firecracker held in the other USA! shout "Cree, cree!" hand, throw it on the ground, make noise like fuse "sssss", then yell loudly "BANG, BANG, BANG!" Fireworks Cheer Flag Cheer Flag Wave Everyone stands, points upward Pretend to raise the flag by Do the regular “wave” where one and shouts, “Skyrocket! Whee!” alternately raising hands over the group at a time starting from one (then whistle), then yell head and “grasping” the rope to side, waves – but announce that it’s a Flag Wave in honor of our Flag. “Boom! Boom!” pull up the flag. Then stand back, salute and say “Ahhh!” Fourth of July Cheer Liberty Bell Yell Rocket Cheer Stand up straight and Ding, Ding, Ding, Dong! Squat down slowly shout "The rockets red Let freedom ring! saying, “5-4-3-2-1” and glare!" then yell, BLAST OFF! And jump into the air. Patriotic Cheer Mount New Citizen Cheer To recognize the hard work of Shout “U.S.A!” and thrust hand learning in order to pass the test with doubled up fist skyward Rushmore Cheer to become a new citizen, have while shouting “Hooray for the Washington, Jefferson, everyone stand, make a salute, Red, White and Blue!” Lincoln, Roosevelt! and say “We salute you!” Soldier Cheer Statue of Liberty USA-BSA Cheer Stand at attention and Cheer One group yells, “USA!” The salute. -

HOW the CAST of TINA GETS INSPIRED by the Legend Herself SPRING HAS ARRIVED on BROADWAY!

SHANDON TRAVEL | SPRING 2020 HOW THE CAST OF TINA GETS INSPIRED by the Legend Herself SPRING HAS ARRIVED ON BROADWAY! SPRING 2020 - BROADWAY SPOTLIGHT BOOK YOUR BROADWAY TICKETS before you fly! Online booking facility now available! Buy great value Broadway tickets before you fly. Enjoying a Broadway show has never been easier! Don’t waste your valuable sight-seeing time waiting in long queues in Times Square or on Broadway. Many shows sell out and you may be disappointed if you wait until the last minute. Book in advance to guarantee the seat of your choice. Check our current schedule for the shows you would like to see by visiting our website at https://www.shandontravel.ie/broadway-tickets You can also call us at 021 4277094 or email [email protected] for ticket information and reservations. Let us help you enjoy the perfect Broadway experience that only Broadway can offer! 021 427 7094 • www.shandontravel.ie/broadway-tickets 76 Grand Parade, Cork, T12 WPV2 Ireland HOW THE CAST OF TINA GETS INSPIRED BY THE LEGEND HERSELF WHAT'S LOVE GOT TO DO WITH IT? Well, everything! Since it opened on ... 2020 SPRING ISSUE 1 BROADWAY SPOTLIGHT Holli’ Conway (Ikette) HOW HAS TINA TURNER INSPIRED OR INFLUENCED YOU? Tina has inspired me because her ... story has no end. From her journey Broadway in November 2019, with Ike, her solo career, her works we’ve loved Tina – The Tina as an author, to this musical. She has Turner Musical. Full disclosure, taught me that as long as you’re alive we loved it when we got a sneak you have space to continue writing peek of it when the show was in your story. -

A Strange Loop

A Strange Loop / Who we are Our vision We believe in theater as the most human and immediate medium to tell the stories of our time, and affirm the primacy and centrality of the playwright to the form. Our writers We support each playwright’s full creative development and nurture their unique voice, resulting in a heterogeneous mix of as many styles as there are artists. Our productions We share the stories of today by the writers of tomorrow. These intrepid, diverse artists develop plays and musicals that are relevant, intelligent, and boundary-pushing. Our plays reflect the world around us through stories that can only be told on stage. Our audience Much like our work, the 60,000 people who join us each year are curious and adventurous. Playwrights is committed to engaging and developing audiences to sustain the future of American theater. That’s why we offer affordably priced tickets to every performance to young people and others, and provide engaging content — both onsite and online — to delight and inspire new play lovers in NYC, around the country, and throughout the world. Our process We meet the individual needs of each writer in order to develop their work further. Our New Works Lab produces readings and workshops to cultivate our artists’ new projects. Through our robust commissioning program and open script submission policy, we identify and cultivate the most exciting American talent and help bring their unique vision to life. Our downtown programs …reflect and deepen our mission in numerous ways, including the innovative curriculum at our Theater School, mutually beneficial collaborations with our Resident Companies, and welcoming myriad arts and education not-for-profits that operate their programs in our studios. -

2019 Silent Auction List

September 22, 2019 ………………...... 10 am - 10:30 am S-1 2018 Broadway Flea Market & Grand Auction poster, signed by Ariana DeBose, Jay Armstrong Johnson, Chita Rivera and others S-2 True West opening night Playbill, signed by Paul Dano, Ethan Hawk and the company S-3 Jigsaw puzzle completed by Euan Morton backstage at Hamilton during performances, signed by Euan Morton S-4 "So Big/So Small" musical phrase from Dear Evan Hansen , handwritten and signed by Rachel Bay Jones, Benj Pasek and Justin Paul S-5 Mean Girls poster, signed by Erika Henningsen, Taylor Louderman, Ashley Park, Kate Rockwell, Barrett Wilbert Weed and the original company S-6 Williamstown Theatre Festival 1987 season poster, signed by Harry Groener, Christopher Reeve, Ann Reinking and others S-7 Love! Valour! Compassion! poster, signed by Stephen Bogardus, John Glover, John Benjamin Hickey, Nathan Lane, Joe Mantello, Terrence McNally and the company S-8 One-of-a-kind The Phantom of the Opera mask from the 30th anniversary celebration with the Council of Fashion Designers of America, designed by Christian Roth S-9 The Waverly Gallery Playbill, signed by Joan Allen, Michael Cera, Lucas Hedges, Elaine May and the company S-10 Pretty Woman poster, signed by Samantha Barks, Jason Danieley, Andy Karl, Orfeh and the company S-11 Rug used in the set of Aladdin , 103"x72" (1 of 3) Disney Theatricals requires the winner sign a release at checkout S-12 "Copacabana" musical phrase, handwritten and signed by Barry Manilow 10:30 am - 11 am S-13 2018 Red Bucket Follies poster and DVD, -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. Adam Ant=English musician who gained popularity as the Amy Adams=Actress, singer=134,576=68 AA lead singer of New Wave/post-punk group Adam and the Amy Acuff=Athletics (sport) competitor=34,965=270 Ants=70,455=40 Allison Adler=Television producer=151,413=58 Aljur Abrenica=Actor, singer, guitarist=65,045=46 Anouk Aimée=Actress=36,527=261 Atif Aslam=Pakistani pop singer and film actor=35,066=80 Azra Akin=Model and actress=67,136=143 Andre Agassi=American tennis player=26,880=103 Asa Akira=Pornographic act ress=66,356=144 Anthony Andrews=Actor=10,472=233 Aleisha Allen=American actress=55,110=171 Aaron Ashmore=Actor=10,483=232 Absolutely Amber=American, Model=32,149=287 Armand Assante=Actor=14,175=170 Alessandra Ambrosio=Brazilian model=447,340=15 Alan Autry=American, Actor=26,187=104 Alexis Amore=American pornographic actress=42,795=228 Andrea Anders=American, Actress=61,421=155 Alison Angel=American, Pornstar=642,060=6 COMPLETEandLEFT Aracely Arámbula=Mexican, Actress=73,760=136 Anne Archer=Film, television actress=50,785=182 AA,Abigail Adams AA,Adam Arkin Asia Argento=Actress, film director=85,193=110 AA,Alan Alda Alison Armitage=English, Swimming=31,118=299 AA,Alan Arkin Ariadne Artiles=Spanish, Model=31,652=291 AA,Alan Autry Anara Atanes=English, Model=55,112=170 AA,Alvin Ailey ……………. AA,Amedeo Avogadro ACTION ACTION AA,Amy Adams AA,Andre Agasi ALY & AJ AA,Andre Agassi ANDREW ALLEN AA,Anouk Aimée ANGELA AMMONS AA,Ansel Adams ASAF AVIDAN AA,Army Archerd ASKING ALEXANDRIA AA,Art Alexakis AA,Arthur Ashe ATTACK ATTACK! AA,Ashley -

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

Blacks Reveal TV Loyalty

Page 1 1 of 1 DOCUMENT Advertising Age November 18, 1991 Blacks reveal TV loyalty SECTION: MEDIA; Media Works; Tracking Shares; Pg. 28 LENGTH: 537 words While overall ratings for the Big 3 networks continue to decline, a BBDO Worldwide analysis of data from Nielsen Media Research shows that blacks in the U.S. are watching network TV in record numbers. "Television Viewing Among Blacks" shows that TV viewing within black households is 48% higher than all other households. In 1990, black households viewed an average 69.8 hours of TV a week. Non-black households watched an average 47.1 hours. The three highest-rated prime-time series among black audiences are "A Different World," "The Cosby Show" and "Fresh Prince of Bel Air," Nielsen said. All are on NBC and all feature blacks. "Advertisers and marketers are mainly concerned with age and income, and not race," said Doug Alligood, VP-special markets at BBDO, New York. "Advertisers and marketers target shows that have a broader appeal and can generate a large viewing audience." Mr. Alligood said this can have significant implications for general-market advertisers that also need to reach blacks. "If you are running a general ad campaign, you will underdeliver black consumers," he said. "If you can offset that delivery with those shows that they watch heavily, you will get a small composition vs. the overall audience." Hit shows -- such as ABC's "Roseanne" and CBS' "Murphy Brown" and "Designing Women" -- had lower ratings with black audiences than with the general population because "there is very little recognition that blacks exist" in those shows. -

Pirate and Hacking Speak Because Your Communicating with the World, Tell Them What You Think

Pirate and Hacking Speak Because your communicating with the world, tell them what you think.... ----------------------------------------------------------------------- Afrikaans Poes / Doos - Pussy Fok jou - Fuck you Jy pis my af - You're pissing me off Hoer - Whore Slet - Slut Kak - Shit Poephol - Asshole Dom Doos - Dump Pussy Gaan fok jouself - Go fuck yourself ------------------------------------------------------------------------ Arabic Koos - cunt. nikomak - fuck your mother sharmuta - whore zarba - shit kis - vagina zib - penis Elif air ab tizak! - a thousand "dicks" in your ass! kisich - pussy Elif air ab dinich - A thousand dicks in your religion Mos zibby! - Suck my dick! Waj ab zibik! - An infection to your dick! kelbeh - bitch (lit a female dog) Muti - jackass Kanith - Fucker Kwanii - Faggot Bouse Tizi - Kiss my ass Armenian Aboosh - Stupid Dmbo, Khmbo - Idiot Myruht kooneh - Fuck your mother Peranuht shoonuh kukneh - The dog should shit in your mouth Esh - Donkey Buhlo (BUL-lo) - Dick Kuk oudelic shoon - Shit eating dog Juge / jugik - penis Vorig / vor - ass Eem juges bacheek doer - Kiss my penis Eem voriga bacheek doer - Kiss my ass Toon vor es - You are an ass Toon esh es - You are a jackass Metz Dzi-zik - Big Breasts Metz Jugik - Big penis ------------------------------------------------------------------------ Bengali baing chood - sister fucker chood - fuck/fucker choodmarani - mother fucker haramjada - bastard dhon - dick gud - pussy khanki/maggi - whore laewra aga - dickhead tor bapre choodi - fuck your dad ------------------------------------------------------------------------ -

ROMA (To Williamson) You Stupid Fucking Cunt. You, Williamson...I'm Talking to You, Shithead...You Just Cost Me Six Thousand Dollars

ROMA (to Williamson) You stupid fucking cunt. You, Williamson...I'm talking to you, shithead...You just cost me six thousand dollars. (pause) Six thousand dollars. And one Cadillac. That's right. What are you going to do about it? What are you goin to do about it, asshole. You fucking shit. Where did you learn your trade. You stupid fucking cunt. You idiot. Whoever told you you could work with men? BAYLEN Could I... ROMA I'm going to have your job, shithead. I'm going downtown and talk to Mitch and Murrray, and I'm going to Lemkin. I don't care whose nephew you are, who you know, whose dick you're sucking on. You're going out, I swear to you, you're going... BAYLEN Hey, fella, let's get this done... ROMA Anyone in this office lives on their wits... (to Baylen) I'm going to be with you in a second. (to Williamson) What you're hired for is to help us--does that seem clear to you? To help us. Not to fuck us up...to help men who are going out there to try to earn a living. You fairy. You company man...I'll tell you something else. I hope you knocked the joint off, I can tell our friend here something might help him catch you. (starts into the room) You want to learn the first rule you'd know if you ever spent a day in your life...you never open your mouth till you know what the shot is. -

Press Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Summer L. Williams Phone #: 617.448.5780 Email: [email protected] www.companyone.org Company One Theatre, in CollaBoration with Suffolk University, Presents THE FLICK High resolution photos availaBle here: http://www.companyone.org/Season15/The_Flick/photos_videos.shtml Boston, MA (FeBruary 2014) — Company One Theatre (C1), recently named "Boston's Best Theatre Company" By The Improper Bostonian, in collaBoration with Suffolk University, present the New England premiere of THE FLICK, By OBIE award winning playwright, Annie Baker. Performances take place FeBruary 20‐March 15, 2014 at the Suffolk University Modern Theatre (525 Washington Street, Boston, MA 02111). Tickets, from $20‐$38 , are onsale now at www.companyone.org. THE FLICK welcomes you to a run‐down movie theatre in Worcester County, MA, where Sam, Avery and Rose are navigating lives as sticky as the soda under the seats. The movies on the Big screen are no match for the tiny Battles and not‐so‐tiny heartBreaks that play out in the empty aisles. Annie Baker (THE ALIENS) and C1 Artistic Director Shawn LaCount reunite with this hilarious and heart‐rending cry for authenticity in a fast‐changing world. With this production, the artists of C1 answer the call from New England fans of one of America’s most celeBrated contemporary playwrights. Boston’s relationship with Annie Baker Began with the C1 award‐winning production of THE ALIENS as part of the Shirley, VT Plays Festival. Annie Baker (who grew up in Amherst, Massachusetts) recently won Both an OBIE for playwriting, and the Susan Smith BlackBurn Prize for THE FLICK. -

O Afastamento Entre Cena E Música, Corpo E Voz No Teatro Musical O

O Afastamento Entre Cena e Música, Corpo e Voz no Teatro Musical: O diluir através dos Viewpoints Larissa Felipe de Melo Cintra Dissertação de Mestrado em Artes Cénicas Versão corrigida e melhorada após defesa pública Junho 2020 Dissertação apresentada para o cumprimento dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de Mestre em Artes Cénicas, realizada sob a orientação científica do Professor Doutor Paulo Filipe Monteiro. Aos meus pais. Agradecimentos Em primeiro lugar, gostaria de agradecer à minha família. Ao Célio e à Margareth, por serem desde sempre os meus maiores apoiantes e companheiros. Por terem sido os meus exemplos vivos de caráter, força e amor; e mais, por mostrarem desde muito cedo, a mim e aos meus irmãos, a importância do conhecimento como nosso legado. Agradeço à Marina e ao Marcel, que sempre abriram os caminhos para mim, tornando possível esse trajeto. Obrigada pela parceria e amor depositados em mim nesta jornada. Sem eles, nada disso seria possível. Agradeço por se fazerem presentes, mesmo a um oceano de distância, e me ensinarem todos os dias um pouco mais de humanidade. Agradeço à Sofia e ao Mateus, por serem os melhores amigos e porto seguro que eu poderia ter. Agradeço por cada palavra de conforto, videochamadas em horários complicados, risadas em dias difíceis e amor imensurável. Agradeço por terem sido ombro e casa, mesmo que de longe. Agradeço a todos os meus colegas de mestrado e faculdade, que vivenciaram essa aventura ao meu lado. Especialmente, à Inês, Mariana, Fábio, Miriam, Gustavo, Júlia e António. Obrigada por todos os momentos que partilhámos, as dores e alegrias, conselhos e descobertas. -

Broadway Theaters

Name Owner Capacity Address City State Al Hirschfeld Theatre Jujamcyn Theaters 1,424 302 W. 45th Street New York NY Ambassador Theatre Shubert Organization 1,125 219 W. 49th Street New York NY American Airlines Theatre Roundabout Theatre Company 740 227 W. 42nd Street New York NY August Wilson Theatre Jujamcyn Theaters 1,228 245 W. 52nd Street New York NY Belasco Theatre Shubert Organization 1,018 111 W. 44th Street New York NY Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre Shubert Organization 1,078 242 W. 45th Street New York NY Booth Theatre Theatre Shubert Organization 766 222 W. 45th Street New York NY Broadhurst Theatre Shubert Organization 1,186 235 W. 44th Street New York NY Broadway Theatre Shubert Organization 1,761 Broadway at 53rd Street New York NY Brooks Atkinson Theatre Nederlander Organization 1,094 256 W. 47th Street New York NY Circle in the Square Theatre Independent 840 1633 Broadway New York NY Cort Theatre Shubert Organization 1,048 138 W. 48th Street New York NY Ethel Barrymore Theatre Shubert Organization 1,096 243 W. 47th Street New York NY Eugene O'Neill Theatre Jujamcyn Theaters 1,066 230 W. 49th Street New York NY Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre Shubert Organization 1,079 236 W. 45th Street New York NY Gershwin Theatre Nederlander Organization 1,933 222 W. 51st Street New York NY Helen Hayes Theatre Second Stage Theatre 597 240 W. 44th Street New York NY Imperial Theatre Shubert Organization 1,433 249 W. 45th Street New York NY John Golden Theatre Shubert Organization 805 252 W. 45th Street New York NY Longacre Theatre Shubert Organization 1,091 220 W.