Making a Way out of No Way: Zora

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Survivors After Suicide Newsletter, Spring 2018

SurvivorSurvivorssAfterSuicideAfterSuicide Your Path Toward Healing Erasing the Stigma – Suicide is Preventable A Program of Didi Hirsch Mental Health Services Spring 2018 A Silver Lining By Sharon Wells Our friendship began where many do, in the continued to meet to share a meal and catch ladies room. up with one another on a fairly regular basis. It was Fall 2007, week three of the eight-week We have few people in our lives that we can Survivors After Suicide (SAS) group at Didi talk with about our losses the way we talk with Hirsch Mental Health Services in Culver City. each other. Others have been supportive but The 90-minute sessions were filled with grief, can’t come close to having the understanding anguish, many tissues and many, many more that comes with experiencing the suicide of tears. We would go to the meetings and then a loved one and going through the support silently and sadly go our separate ways feeling group together. I know that 11 years after the broken beyond repair, trying to process our death of my brother, I can talk about him with feelings about loved ones choosing to end them and if tears or anger appear, I’ll never their lives. be judged, and more importantly to me, he’ll never be judged. Throughout our journey, I was there because a year earlier, my baby we’ve come to terms with the likely fact that Sharon Wells remembers her brother Jerry brother Jerry decided he had enough of his the pain will revisit us throughout our lives, yet and the healing bonds of friendship. -

Sweat: the Exodus from Physical and Mental Enslavement to Emotional and Spiritual Liberation

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2007 Sweat: The Exodus From Physical And Mental Enslavement To Emotional And Spiritual Liberation Aqueelah Roberson University of Central Florida Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Roberson, Aqueelah, "Sweat: The Exodus From Physical And Mental Enslavement To Emotional And Spiritual Liberation" (2007). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 3319. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/3319 SWEAT: THE EXODUS FROM PHYSICAL AND MENTAL ENSLAVEMENT TO EMOTIONAL AND SPIRITUAL LIBERATION by AQUEELAH KHALILAH ROBERSON B.A., North Carolina Central University, 2004 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in the Department of Theatre in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2007 © 2007 Aqueelah Khalilah Roberson ii ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is to showcase the importance of God-inspired Theatre and to manifest the transformative effects of living in accordance to the Word of God. In order to share my vision for theatre such as this, I will examine the biblical elements in Zora Neale Hurston’s short story Sweat (1926). I will write a stage adaptation of the story, while placing emphasis on the biblical lessons that can be used for God-inspired Theatre. -

Jonah's Gourd Vine and South Moon Under As New Southern Pastoral

Re-Visioning Nature: Jonah’s Gourd Vine and South Moon Under as New Southern Pastoral Kyoko Shoji Hearn Introduction Despite their well-known personal correspondence, few critical studies read the works of two Southern women writers, Zora Neale Hurston and Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings together. Both of them began to thrive in their literary career after they moved to Florida and published their first novels, Jonah’s Gourd Vine (1934) and South Moon Under (1933). When they came down to central Florida (Hurston, grown up in Eatonville, and coming back as an anthropological researcher, Rawlings as an owner of citrus grove property) in the late 1920s, the region had undergone significant social and economic changes. During the 1920s, Florida saw massive influx of people from varying social strata against the backdrop of the unprecedented land boom, the expansion of the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad, the statewide growth of tourism, and the development of agriculture including the citrus industry in central Florida.1 Hurston’s and Rawlings’s relocation was a part of this mobility. Rawlings’s first visit to Florida occurred in March 1928, when she and her husband Charles had a vacation trip. Immediately attracted by the region’s charm, the couple migrated from Rochester, New York, to be a part of booming citrus industry.2 Hurston was aware of the population shift taking place in her home state and took it up in her work. At the opening of Mules and Men (1935), she writes: “Dr. Boas asked me where I wanted to work and I said, ‘Florida,’ and gave, as my big reason, that ‘Florida is a place that draws people—white people from all over the world, and Negroes from every Southern state surely and some from the North and West.’ So I knew that it was possible for me to get a cross section of the Negro South in the one state” (9). -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Dianne Mcintyre

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Dianne McIntyre Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: McIntyre, Dianne Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Dianne McIntyre, Dates: June 18, 2004 Bulk Dates: 2004 Physical 7 Betacame SP videocasettes (3:23:08). Description: Abstract: Choreographer and dancer Dianne McIntyre (1946 - ) founded her own dance company, Sounds in Motion, which was active during the 1970s and 1980s. McIntyre's special interest in history and culture as it relates to dance had led to many projects for her in the areas of concert dance, theatre, film and television. McIntyre was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on June 18, 2004, in Cleveland, Ohio. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2004_085 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Choreographer, dancer, and director Dianne McIntyre was born in 1946 in Cleveland, Ohio to Dorothy Layne McIntyre and Francis Benjamin McIntyre. She attended Cleveland Public Schools and graduated from John Adams High School in 1964. As a child, she studied ballet with Elaine Gibbs and modern dance with Virginia Dryansky and earned a BFA degree in dance from The Ohio State University. Following her move to New York City in 1970, McIntyre founded her own company, Sounds in Motion, in 1972. McIntyre and her company toured and performed in concert with Olu Dara, Lester Bowie, Cecil Taylor, Max Roach, Butch Morris, David Murray, Hamiet Bluiett, Ahmed Abdullah, Don Pullen, Anthony Davis, Abbey Lincoln, Sweet Honey in the rock, Hannibal, Oliver Lake, and countless others musicians until 1988, when she closed it to have more time to explore new areas of creative expression. -

Alien Love- Passing, Race, and the Ethics of the Neighbor in Postwar

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Alien Love: Passing, Race, and the Ethics of the Neighbor in Postwar African American Novels, 1945-1956 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy In English By Hannah Wonkyung Nahm 2021 © Copyright by Hannah Wonkyung Nahm 2021 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Alien Love: Passing, Race, and the Ethics of the Neighbor in Postwar African American Novels, 1945-1956 by Hannah Wonkyung Nahm Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Los Angeles, 2021 Professor King-Kok Cheung, Co-Chair Professor Richard Yarborough, Co-Chair This dissertation examines Black-authored novels featuring White (or White-passing) protagonists in the post-World War II decade (1945-1956). Published during the fraught postwar political climate of agitation for integration and the continual systematic racism, many novels by Black authors addressed the urgent topic of interracial relationality, probing the tabooed question of whether Black and White can abide in love and kinship. One of the prominent—and controversial—literary strategies sundry Black novelists used in this decade was casting seemingly raceless or ambiguously-raced characters. Collectively, these novels generated a mixture of critical approval and dismissal in their time and up until recently, marginalized from the African American literary tradition. Even more critically overlooked than the ostensibly raceless project was the strategic mobilization of the trope of passing by some midcentury Black ii writers to imagine the racial divide and possible reconciliation. This dissertation intersects passing with postwar Black fiction that features either racially-anomalous or biracial central characters. Examining three novels from this historical period as my case studies, I argue that one of the ways in which Black writers of this decade have imagined the possibility of interracial love—with all its political pitfalls and ethical imperatives —is through the trope of passing. -

The New Selection for Oprah's Book Club 2.0! RUBY a Novel by Cynthia Bond

The New Selection for Oprah’s Book Club 2.0! RUBY A Novel By Cynthia Bond Select Praise for RUBY “Bond proves to be a powerful literary force, a writer whose unflinching yet lyrical prose is reminiscent of Toni Morrison’s.” —O, The Oprah Magazine “Channeling the lyrical phantasmagoria of early Toni Morrison and the sexual and racial brutality of the 20th century east Texas, Cynthia Bond has created a moving and indelible portrait of a fallen woman ... Bond traffics in extremely difficult subjects with a grace and bigheartedness that makes for an accomplished, enthralling read.” —San Francisco Chronicle “In Ruby, Bond has created a heroine worthy of the great female protagonists of Toni Morrison … and Zora Neale Hurston … Bond’s style of writing is as magical as an East Texas sunrise, with phrases so deftly carved, the reader is often distracted from the brutality described by the sheer beauty of the language.” —Dallas Morning News An Indie Next Pick, Barnes & Noble “Discover Great New Writers” Selection, Library Journal “Breakout Literary Fiction” Pick, and a Southern Living Book Club Selection! In describing her debut novel, RUBY (Hogarth; February 10, 2015), Cynthia Bond has said “there are moments, spices, that have been stirred in slowly—from my life and from the stories of others.” She has drawn upon her own experiences, her family’s history, and the heartbreaking tales she’s heard through the years working with homeless and at-risk youth, including the brutal devastation of human trafficking, and woven these threads together to create a story that is truly unforgettable. -

Single Handed Sailing Ahead

October 1, 2014: The latest edition of this book has now been published on real paper and Kindle e-book by McGraw-Hill. The book is available from Amazon, Chapters-Indigo and other quality booksellers. The new edition has several new chapters and major additions, including: Extended interviews with Craig Horsfield (Mini 6.50), Joe Harris (Class 40) and Ryan Breymaier (IMOCA 60) about sailing their performance racers. A whole chapter on keels, keeping the boat upright and reducing leeway, including water ballast, canting keels, dagger boards and the DSS wing. A big section and lessons from Jessica Watson’s collision with a freighter, including the report from The Australian Transportation Safety Bureau. A long interview and photos from Ruben Gabriel on every singlehander’s dream; what it’s like to break a mast and repair it – half way to Hawaii. Dealing with hull punctures in real life (not the movie version). A long talk with 3-time circumnavigator Jeanne Socrates on living aboard. Discussions with singlehanders about their real life medical emergencies. Dan Alonso’s story of rescuing another singlehander in horrible weather. The good way and not-so-good way to hit a rock, from my own experience. And of course the whole book has now been professionally edited and printed. Enjoy! Thoughts, Tips, Techniques & Tactics For Singlehanded Sailing Andrew Evans ThirdThird EditionEdition Foreword by Bruce Schwab This book is only available as a free download from The Singlehanded Sailing Society at www.sfbaysss.org/tipsbook Front and back covers by Andrew Madding, club photographer for the Royal Victoria Yacht Club. -

Enacting Cultural Identity : Time and Memory in 20Th-Century African-American Theater by Female Playwrights

Enacting Cultural Identity: Time and Memory in 20th-Century African-American Theater by Female Playwrights Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades des Doktors der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) vorgelegt von Simone Friederike Paulun an der Geisteswissenschaftliche Sektion Fachbereich Literaturwissenschaft Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 13. Februar 2012 Referentin: Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. Aleida Assmann Referentin: PD Dr. Monika Reif-Hülser Konstanzer Online-Publikations-System (KOPS) URL: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:352-0-269861 Acknowledgements 1 Acknowledgements This dissertation would not have been possible without the guidance and support of several individuals who in one way or another contributed to the writing and completion of this study. It gives me a great pleasure to acknowledge the help of my supervisor Prof Dr. Aleida Assmann who has supported me throughout my thesis and whose knowledge, guidance, and encouragement undoubtedly highly benefited my project. I would also like to thank PD Dr. Monika Reif-Hülser for her sustained interest in my work. The feedback that I received from her and the other members of Prof. Assmann’s research colloquium was a very fruitful source of inspiration for my work. The seeds for this study were first planted by Prof. David Krasner’s course on African- American Theater, Drama, and Performance that I attended while I was an exchange student at Yale University, USA, in 2005/2006. I am immensely grateful to him for introducing me to this fascinating field of study and for sharing his expert knowledge when we met again in December 2010. A further semester of residence as a visiting scholar at the African American Department at Yale University in 2010 enabled me to receive invaluable advice from Prof. -

Grammy® Awards 2018

60th Annual Grammy Awards - 2018 Record Of The Year Childish Gambino $13.98 Awaken My Love. Glassnote Records GN 20902 UPC: 810599021405 Contents: Me and Your Mama -- Have Some Love -- Boogieman -- Zombies -- Riot -- Redbone -- California -- Terrified -- Baby Boy -- The Night Me and Your Mama Met -- Stand Tall. http://www.tfront.com/p-449560-awaken-my-love.aspx Luis Fonsi $20.98 Despacito & Mis Grandes Exitos. Universal Records UNIV 5378012 UPC: 600753780121 Contents: Despacito -- Despacito (Remix) [Feat. Justin Bieber] -- Wave Your Flag [Feat. Luis Fonsi] -- Corazón en la Maleta -- Llegaste TÚ [Feat. Juan Luis Guerra] -- Tentación -- Explícame -- http://www.tfront.com/p-449563-despacito-mis-grandes-exitos.aspx Jay-Z. $13.98 4:44. Roc Nation Records ROCN B002718402 UPC: 854242007583 Contents: Kill Jay-Z -- The Story of O.J -- Smile -- Caught Their Eyes -- (4:44) -- Family Feud -- Bam -- Moonlight -- Marcy Me -- Legacy. http://www.tfront.com/p-449562-444.aspx Kendrick Lamar $13.98 Damn [Explicit Content]. Aftermath / Interscope Records AFTM B002671602 UPC: 602557611755 OCLC Number: 991298519 http://www.tfront.com/p-435550-damn-explicit-content.aspx Bruno Mars $18.98 24k Magic. Atlantic Records ATL 558305 UPC: 075678662737 http://www.tfront.com/p-449564-24k-magic.aspx Theodore Front Musical Literature, Inc. ● 26362 Ruether Avenue ● Santa Clarita CA 91350-2990 USA Tel: (661) 250-7189 Toll-Free: (844) 350-7189 Fax: (661) 250-7195 ● [email protected] ● www.tfront.com - 1 - 60th Annual Grammy Awards - 2018 Album Of The Year Childish Gambino $13.98 Awaken My Love. Glassnote Records GN 20902 UPC: 810599021405 Contents: Me and Your Mama -- Have Some Love -- Boogieman -- Zombies -- Riot -- Redbone -- California -- Terrified -- Baby Boy -- The Night Me and Your Mama Met -- Stand Tall. -

Vision a Connected World Where Diversity of Thought Matters

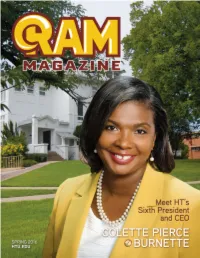

Mission HT nurtures a legacy of leadership and excellence in education, connecting knowledge, power, passion, and values. Vision A connected world where diversity of thought matters. Accreditation Huston-Tillotson University is accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges to award associate, baccalaureate and masters degrees. Contact the Commission on Colleges at 1866 Southern Lane, Decatur, Georgia 30033-4097 or call 404-679-4500 for questions about the accreditation of Huston-Tillotson University. From the President Everyday presents new opportunities to tell the world about this historic jewel in the heart of Austin, Texas— Huston-Tillotson University. I have met extraordinary students, passionate faculty and staff, proud alumni, and supportive community leaders. Thank you for making my transition a smooth one. was particularly moved by the motto that the leaders of the Samuel Huston College and Tillotson College crafted after merging the two institutions into one: In Union, Strength! These words are a testament to the hopefulness that the Ileaders envisioned. HT flourishes as a result of the combined strength of those who hold it dear, and I am proud to be a part of this great legacy. This edition of the Ram Magazine highlights the progress of the University and promotes the successes of faculty and students. It is the culminating work of President Emeritus Dr. Larry L. Earvin. I recognize the plateau of this labor of devotion to HT as my platform to continue moving the University forward. His culminating work is my platform to continue the progress of HT. As you read through these pages, take a minute to note many HT accomplishments. -

Vol. II. Issue. II June 2011 C O N T E N

www.the-criterion.com The Criterion: An International Journal in English ISSN 0976-8165 Vol. II. Issue. II June 2011 C O N T E N T S Articles From Ignorance to knowledge: A Study of J. M. Synge’s The Well of the Saints [PDF] Arvind M. Nawale An Exploration of Narrative Technique in Gita Mehta’s A River Sutra [PDF] Mrs. Madhuri Bite De’s fiction: A Protest Against Malist Culture [PDF] Nishi Bala Chauhan Role of the English Language/Literature in Quality Education and Teacher Development [PDF] Baby Pushpa Sinha Feminist Concerns in Verginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own [PDF] Sachin Vaman Londhe Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London (1933) : A Documentary on Hunger, Starvation and Poverty [PDF] N. R. Sawant Chetan Bhagat: A Libertarian [PDF] R. A. Vats, Rakhi Sharma Postmodern Trends in the Novels of Amitav Ghosh [PDF] Prof. R. Chenniappan, R. Saravana Suresh Translating Amrit Lal Nagar’s Nachyo Bahut Gopal: Some Considerations—Casteist and Linguistic. [PDF] Sheeba Rakesh Vol.II Issue II 1 June 2011 www.the-criterion.com The Criterion: An International Journal in English ISSN 0976-8165 Salman Rushdie as a Children’s Writer: Reading Haroun And The Sea Of Stories (1990) and Luka And The Fire Of Life (2010) [PDF] Ved Mitra Shukla When Mr.Pirzada Creates Anuranan: A Study of Home Through the Bong Connection [PDF] Dhritiman Chakraborty Using Internet in Improving One’s English Language Skills: 50 Informative, Educative & Entertaining Websites [PDF] Vangeepuram Sreenathachary Critical Review on the MLA Handbook (7th Edition) [PDF] Shahila Zafar, -

Zora Neale Hurston Daryl Cumber Dance University of Richmond, [email protected]

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository English Faculty Publications English 1983 Zora Neale Hurston Daryl Cumber Dance University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/english-faculty-publications Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Literature Commons, Caribbean Languages and Societies Commons, Literature in English, North America, Ethnic and Cultural Minority Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Dance, Daryl Cumber. "Zora Neale Hurston." In American Women Writers: Bibliographical Essays, edited by Maurice Duke, Jackson R. Bryer, and M. Thomas Inge, 321-51. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1983. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the English at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 12 DARYL C. DANCE Zora Neale Hurston She was flamboyant and yet vulnerable, self-centered and yet kind, a Republican conservative and yet an early black nationalist. Robert Hemenway, Zora Neale Hurston. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1977 There is certainly no more controversial figure in American literature than Zora Neale Hurston. Even the most common details, easily ascertainable for most people, have been variously interpreted or have remained un resolved issues in her case: When was she born? Was her name spelled Neal, Neale, or Neil? Whom did she marry? How many times was she married? What happened to her after she wrote Seraph on the Suwanee? Even so immediately observable a physical quality as her complexion sparks con troversy, as is illustrated by Mary Helen Washington in "Zora Neale Hurston: A Woman Half in Shadow," Introduction to I Love Myself When I Am Laughing .