Bialik in the Ghettos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peter Black Odilo Globocnik, Nazi Eastern Policy, and the Implementation of the Final Solution

www.doew.at – Dokumentationsarchiv des österreichischen Widerstandes (Hrsg.), Forschungen zum Natio- nalsozialismus und dessen Nachwirkungen in Österreich. Festschrift für Brigitte Bailer, Wien 2012 91 Peter Black Odilo Globocnik, Nazi Eastern Policy, and the Implementation of the Final Solution During the spring of 1943, while on an inspection tour of occupied Poland that included a briefing on the annihilation of the Polish Jews, SS Personnel Main Office chief Maximilian von Herff characterized Lublin District SS and Police Leader and SS-Gruppenführer Odilo Globocnik, in the following way: “A man fully charged with all possible light and dark sides. Little concerned with ap- pearances, fanatically obsessed with the task, [he] engages himself to the limit without concern for health or superficial recognition. His energy drives him of- ten to breach existing boundaries and to forget the boundaries established for him within the [SS-] Order – not out of personal ambition, but much more for the sake of his obsession with the matter at hand. His success speaks unconditionally for him.”1 Von Herff’s analysis of Globocnik’s reflected a consistent pattern in the ca- reer of the Nazi Party organizer and SS officer, who characteristically atoned for his transgressions of the National Socialist code of behavior by fanatical pursuit and implementation of core Nazi goals.2 Globocnik was born to Austro-Croat parents on April 21, 1904 in multina- tional Trieste, then the principal seaport of the Habsburg Monarchy. His father’s family had come from Neumarkt (Tržič), in Slovenia. Franz Globocnik served as a Habsburg cavalry lieutenant and later a senior postal official; he died of pneumonia on December 1, 1919. -

Lublin Ghetto

Coordinates: 51°15′11″N 22°34′18″E Lublin Ghetto The Lublin Ghetto was a World War II ghetto created by Lublin Ghetto Nazi Germany in the city of Lublin on the territory of General Government in occupied Poland.[1] The ghetto inmates were mostly Polish Jews, although a number of Roma were also brought in.[2] Set up in March 1941, the Lublin Ghetto was one of the first Nazi-era ghettos slated for liquidation during the most deadly phase of the Holocaust in occupied Poland.[3] Between mid-March and mid-April 1942 over 30,000 Jews were delivered to their deaths in cattle trucks at the Bełżec extermination camp and additional 4,000 at Majdanek.[1][4] Two German soldiers in the Lublin Ghetto, May 1941 Contents Also known as German: Ghetto Lublin or Lublin Reservat History Liquidation of the Ghetto Location Lublin, German-occupied Poland See also Incident type Imprisonment, forced labor, References starvation, exile External links Organizations Nazi SS Camp deportations to Belzec extermination camp and Majdanek History Victims 34,000 Polish Jews Already in 1939–40, before the ghetto was officially pronounced, the SS and Police Leader Odilo Globocnik (the SS district commander who also ran the Jewish reservation), began to relocate the Lublin Jews further away from his staff headquarters at Spokojna Street,[5] and into a new city zone set up for this purpose. Meanwhile, the first 10,000 Jews had been expelled from Lublin to the rural surroundings of the city beginning in early March.[6] The Ghetto, referred to as the Jewish quarter (or Wohngebiet der Juden), was formally opened a year later on 24 March 1941. -

Index of Subjects

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-83875-7 - Jewish Forced Labor Under the Nazis: Economic Needs and Racial Aims, 1938-1944 Wolf Gruner Index More information Index of Subjects Aktion Erntefest, 271 Autobahn camps, 286 Aktion Hase, 96 acceptance/rejection of Jews for, 197, Aktion Mitte B, 97 198 Aktion Reinhard, 258 administration of by private companies, Aktion T4, 226 203 Allgemeine Ortskrankenkasse (AOK). See closing of, 208, 209, 211 General Local Health Insurance control of by Autobahn authorities, 199, Provider. 203, 213, 219 Annexation of Austria. See Anschluss. control of by SS (Schmelt), 214, 223 Anschluss (annexation of Austria), xvi, xxii, employing Polish Jews, 183, 198, 203, 3, 105, 107, 136, 278 217, 286 Anti-Jewish policy locations of, 203, 212, 219, 220 before 1938, xx, xxii, xxiv redesignation of as “Zwangsarbeitslager,” central measures in, xxi, xxii, xxiii 223 consequences of for Jews, xvi, 107, 109, regulations for, 199, 200, 203, 212 131, 274 See also Fuhrer’s¨ road and Schmelt forced contradiction in, 109 labor camps. diminished SS role in, 240, 276 Autobahn construction management division of labor principle in, xvii, xviii, headquarters (Oberste Bauleitung der xxiv, 30, 112, 132, 244, 281, 294 Reichsautobahnen) effect of war on, 8, 9, 126, 141, 142 in Austria, 127 forced labor as element of, x, xii, xiii, 3, 4, in Berlin, 199, 200, 202, 203, 204, 205, 177, 276 206 in Austria, 136 in Breslau, 204, 205, 211, 212, 220, local-central interaction in, xx, xxi, xxii 222 local measures in, xxi, xxii, xxiii, 150, in Cologne, 205 151 in Danzig, 203, 204, 205 measures implementing, 151, 172, 173, See also Reich Autobahn Directorates. -

German Economic Policy and Forced Labor of Jews in the General Government, 1939–1943 Witold Wojciech Me¸Dykowski

Macht Arbeit Frei? German Economic Policy and Forced Labor of Jews in the General Government, 1939–1943 Witold Wojciech Me¸dykowski Boston 2018 Jews of Poland Series Editor ANTONY POLONSKY (Brandeis University) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: the bibliographic record for this title is available from the Library of Congress. © Academic Studies Press, 2018 ISBN 978-1-61811-596-6 (hardcover) ISBN 978-1-61811-597-3 (electronic) Book design by Kryon Publishing Services (P) Ltd. www.kryonpublishing.com Academic Studies Press 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA P: (617)782-6290 F: (857)241-3149 [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com This publication is supported by An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-1-61811-907-0. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. To Luba, with special thanks and gratitude Table of Contents Acknowledgements v Introduction vii Part One Chapter 1: The War against Poland and the Beginning of German Economic Policy in the Ocсupied Territory 1 Chapter 2: Forced Labor from the Period of Military Government until the Beginning of Ghettoization 18 Chapter 3: Forced Labor in the Ghettos and Labor Detachments 74 Chapter 4: Forced Labor in the Labor Camps 134 Part Two Chapter -

The Holocaust (Shoah) (1939-1945)

The Holocaust (Shoah) (1939-1945) This essay is not meant to be comprehensive. Rather, this is a narrative summary of my presentation. Holocaust historian Karl Schleunes wrote about the “Twisted Road to Auschwitz” that explored how the Nazis ended up building camps of mass murder. It is a useful description as it allows us to blend together some of the myriad forces acting together to create a “perfect storm.” As survivor Emil Fackenheim writes, “The murder camp was not an accidental by-product of the Nazi empire. It was its essence.” Nazi Germany was on a trajectory of mass murder and atrocity from its onset. The unfolding of genocides in Europe is a complex phenomenon, but for our purposes we will focus on: Nazi “ideology” and the bureaucratic, competitive, feudal nature of the Nazi state; process and innovation; Hitler’s function as leader and individual initiatives of “working towards the Führer”; the influence of the unfolding wartime situation; and the influence of location, specifically Eastern Europe. Ideology is not something that can be imposed “from the top.” Rather, ideology is a packaged expression of cultural symbols, desires, and perspectives that “make sense” to a public at large. Holocaust historian Doris Bergen sums up Nazi ideology with the phrase, “Race and Space.” Nazism was rooted in racial theory that had become popular within professional circles by the turn of the twentieth century. For the Nazis, “racial” survivor was predicated on a social Darwinist view of natural competition and survival. Not only was it necessary to weed out “threatening” gene pools from the “Aryan” it was also necessary for the “Aryan” to find living space or lebensraum. -

Military History Anniversaries 0316 Thru 033119

Military History Anniversaries 16 thru 31 MAR Events in History over the next 15 day period that had U.S. military involvement or impacted in some way on U.S military operations or American interests Mar 16 1802 – West Point: U.S. Military Academy established » The United States Military Academy–the first military school in the United States–is founded by Congress for the purpose of educating and training young men in the theory and practice of military science. Located at West Point, New York, the U.S. Military Academy is often simply known as West Point. Located on the high west bank of New York’s Hudson River, West Point was the site of a Revolutionary-era fort built to protect the Hudson River Valley from British attack. In 1780, Patriot General Benedict Arnold, the commander of the fort, agreed to surrender West Point to the British in exchange for 6,000 pounds. However, the plot was uncovered before it fell into British hands, and Arnold fled to the British for protection. Ten years after the establishment of the U.S. Military Academy in 1802, the growing threat of another war with Great Britain resulted in congressional action to expand the academy’s facilities and increase the West Point corps. Beginning in 1817, the U.S. Military Academy was reorganized by superintendent Sylvanus Thayer–later known as the “father of West Point”–and the school became one of the nation’s finest sources of civil engineers. During the Mexican-American War, West Point graduates filled the leading ranks of the victorious U.S. -

A Tangled Web

REVISED JANUARY 2016 A TANGLED WEB Polish-Jewish Relations in Wartime Northeastern Poland and the Aftermath (PART TWO) Mark Paul PEFINA Press Toronto 2016 © Mark Paul and Polish Educational Foundation in North America (Toronto), 2016 A Tangled Web is a revised and expanded version of an article that appeared in The Story of Two Shtetls, Brańsk and Ejszyszki, Part Two published by The Polish Educational Foundation in North America, 1998 Table of Contents Part Two: Partisan Relations and Warfare Polish Partisans, Jewish Partisans, Soviet Partisans …3 An Overview of Polish-Soviet Wartime Relations …20 Soviet Designs …60 The Spiral Begins …64 Acting on Orders to Eliminate the Polish Partisans …84 Jewish Historiography ..102 Jewish Partisans Join in Soviet Operations Against Polish Partisans ..126 German Raids, the Soviet Peril, and Inhospitable Jews ..160 Local Help, Food Forays and Pillaging ..206 Procuring Arms and Armed Raids ..248 Villagers Defend Themselves Against Raids ..272 The Raids Intensify ..282 2 Part Two: Partisan Relations and Warfare “One should not close one’s eyes to the fact that Home Army units in the Wilno area were fighting against the Soviet partisans for the liberation of Poland. And that is why the Jews who found themselves on the opposing side perished at the hands of Home Army soldiers —as enemies of Poland, and not as Jews.” Yisrael Gutman Historian, Yad Vashem Institute Polish Partisans, Jewish Partisans, Soviet Partisans According to Holocaust historians, the Jews who escaped the Nazi ghettos in northeastern -

The Holocaust in Historical Perspective Yehuda Bauer

The Holocaust The Historicalin Perspective Bauer Yehuda The Holocaust in Historical The Holocaust Perspective Yehuda Bauer in Historical Between 1941 and 1945, the Nazi regime em barked on a deliberate policy of mass murder that resulted in the deaths of nearly six million Jews. What the Nazis attempted was nothing less than the total physical annihilation of the Perspective Jewish people. This unprecedented atrocity has come to be known as the Holocaust. In this series of four essays, a distinguished his torian brings the central issues of the holocaust to the attention of the general reader. The re sult is a well-informed, forceful, and eloquent work, a major contribution to Holocaust histo Yehuda Bauer riography. The first chapter traces the background of Nazi antisemitism, outlines the actual murder cam paign, and poses questions regarding the reac tion in the West, especially on the part of American Jewish leadership. The second chap ter, “Against Mystification,” analyzes the vari ous attempts to obscure what really happened. Bauer critically evaluates the work of historians or pseudohistorians who have tried to deny or explain away the Holocaust, as well as those who have attempted to turn it into a mystical experience. Chapter 3 discusses the problem of the “by stander.” Bauer examines the variety of re sponses to the Holocaust on the part of Gen tiles in Axis, occupied, Allied, and neutral lands. He attempts to establish some general (continued on back flap) The Holocaust The Historicalin Perspective Bauer Yehuda The Holocaust in Historical The Holocaust Perspective Yehuda Bauer in Historical Between 1941 and 1945, the Nazi regime em barked on a deliberate policy of mass murder that resulted in the deaths of nearly six million Jews. -

Ordinary Men, Extraordinary Photos by Judith Levin and Daniel Uziel

Ordinary Men, Extraordinary Photos by Judith Levin and Daniel Uziel Photographs from the Holocaust era are among the most horrifying visual documents produced since the invention of photography. Several famous photos taken during the Holocaust have become its symbols and are widely displayed in exhibitions, films, and albums. Despite the wide dissemination of photographs from the Holocaust, historical research has hardly availed itself of them, and little has been written about the methodology of their use.1 Re-examination of photographs from the Holocaust, coupled with the knowledge accrued in the past few years, may give us a new perspective on the importance of these photographs as a historical source. This article illuminates the intrinsic research potential of the photographs by presenting and examining photos taken by German soldiers and police in their service postings in Eastern Europe. Many such photos, appropriated from German prisoners or lifted from the pockets of German soldiers and prisoners who had been killed, made their way to various private collections and archives after the war. These photos document, inter alia, the life of Jews in the ghettos and the abuse and murder to which they were subjected.2 The private collections of soldiers and policemen also include photos that portray them together with their victims before, after, and during abuse or murder. The collections also 1 See, for example, Sybil Milton, "Images of the Holocaust," in Holocaust and Genocide Studies, 1:1 (1986), pp. 27-61; 1:2 (1986), pp. 193-216; Frank Daba Smith, Photography and the Holocaust, unpublished dissertation., (London, Leo Baeck College, 1994); Asthetik der Fotografie, Heft 55 (1995). -

Yad-Vashem-Holocaust-Timeline.Pdf

Timeline Jump to: 1914-1933 1934-1939 1940-1945 View as timeline 8/1/1914 World War I Begins Following the crisis touched off by the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand of Austria in Sarajevo, Germany declared war on Russia and additional countries joined the war within several days. The Central Powers (Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire) fought against the Allied powers (Great Britain, France, and Russia). In November 1914, Turkey sided with the Central Powers; in 1915, Italy joined the Allies. 4/24/1915 The Armenian Genocide In the first year of World War I, in the course of war between Turkey and Russia in the Armenian provinces of Turkey, the Turks questioned the Armenians' loyalties and drove them out of their homes. At least 1 million Armenians, about half of the Armenian population in Turkey, were murdered in the expulsion by the Turks. 11/2/1917 Balfour Declaration The British Foreign Secretary, Lord Arthur James Balfour, proclaimed Britain's support of the creation of a national home for the Jews in Palestine. This declaration, given after British forces had already taken control of the southern part of Palestine and were about to occupy its north, transformed the Zionist vision into a political program that seemed attainable. 11/7/1917 Communist Revolution in Russia In response to Russia's defeat on the front, Czar Nicholas II was dethroned in a revolution in March 1917 and a new government of mixed liberal-conservative complexion came into being. As political deadlock and defeats on the front continued, the socialists gained in popularity and their radical wing, the Bolshevik party, under Lenin, called for immediate peace and apportionment of land to the peasants. -

The Program for the Tour

TRIP TO POLAND, MAY 2015 THE PROGRAM OF THE TOUR Foto: Ewa Held Day 1: Warsaw Arrival in Warsaw - transfer to the hotel Depending on the arrival time - short afternoon tour of historic Warsaw If arrival on Wednesday-start of the tour on Thursday morning- tour of historic Warsaw and the Museum of the History of Polish Jews Accommodation in Warsaw - to be confirmed Dinner at the hotel or city restaurant Theatre performance or Concert? Foto: Renata Zawadzka-Ben Dor Day 2: Warsaw After breakfast - full day tour: “The Warsaw Ghetto” (the former area of the Warsaw ghetto - remains of the ghetto walls, synagogue, monuments and historical sites including the Monument to the Heroes of the Warsaw Ghetto, the Remembrance Path, Mila 18 Monument and Umschlagplatz Monument, Jewish cemetery, Optional – Jewish Historical Institute (exhibition and film), Optional – the Museum of the History of Polish Jews (note one optional admission possible – according to your choice, the second one can be scheduled on the first day depending on the arrival time) During the day free time for lunch Accommodation in Warsaw – to be confirmed Shabbat Dinner Treblinka Concentration Camp sign by David Shankbone CC BY-SA 3.0 szylt znajduje sie w Yed Vashem Day 3: Tykocin - Lopuchowo - Treblinka After breakfast – departure for full day tour by bus: Tykocin: once an important trade centre owned by Polish kings, by 1800 became a typical Jewish shtetl. Before WW2, the town had 5,000 inhabitants, half of them Jewish. All of the 2,500 Jewish residents of Tykocin were taken to the nearby Lopuchowo forest and shot by the Nazis in the Summer of 1941. -

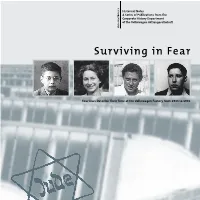

Surviving in Fear

Historical Notes A Series of Publications from the Corporate History Department of the Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft Historical Notes 3 Surviving in Fear Four Jews Describe Their Time at the Volkswagen Factory from 1943 to 1945 The authors Moshe Shen, born 1930 · Julie Nicholson, born 1922 · Sara Frenkel, born 1922 · Sally Perel, born 1925 · Susanne Urban, born 1968 Imprint Editors Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft Corporate History Department: Manfred Grieger, Ulrike Gutzmann Translation SDL Multilingual Services Design con©eptdesign, Günter Illner, Bad Arolsen Print Druckerei E. Sauerland, Langenselbold ISSN 1615-1593 ISBN 978-3-935112-22-2 © Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft Wolfsburg 2005 New edition 2013 Surviving in Fear Four Jews Describe Their Time at the Volkswagen Factory from 1943 to 1945 With a contribution by Susanne Urban Jewish Remembrance. Jewish Forced Labourers and Jews with False Papers at the Volkswagen Factory Susanne Urban _____ P. 6 Moshe Shen _____ P. 18 Julie Nicholson _____ P. 30 Jewish Remembrance. For Concentration Camp Inmates like us, Survival To Preserve History and Learn its Lessons is an Jewish Forced Labourers and Jews with False Papers was a Question of Time Essential Task at the Volkswagen Factory I. Forced labour at the Volkswagen factory Childhood and a strict father Sheltered childhood II. Structures of remembrance Too late to flee Arrested in Budapest III. Four lifelines Auschwitz Auschwitz The selection of prisoners for the Volkswagen factory Everyday life in Auschwitz Isolation and work on the “secret