SFU Library Thesis Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mode of Flow of Saskatchewan Glacier Alberta, Canada

Mode of Flow of CO Saskatchewan Glacier t-t Alberta, Canada GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 351 OJ be o PQ 1960 Mode of Flow of Saskatchewan Glacier Alberta, Canada By MARK F. MEIER GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 351 Measurement and analysis of ice movement, deformation, and structural features of a typical valley glacier UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON: 1960 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRED A. SEATON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director The U.S. Geological Survey Library has catalogued this publication as follows: Meier, Mark Frederick, 1925 Mode of flow of Saskatchewan Glacier, Alberta, Canada. Washington, U.S. Govt. Print. Off., 1959. ix, 70 p. illus. (1 col.) maps, diagrs., profiles, tables. 30 cm. (U.S. Geological Survey. Professional paper 351) Part of illustrative matter folded in pocket. Measurement and analysis of ice movement, deformation, and structural features of a typical valley glacier. Bibliography: p. 67-68. 1. Glaciers Alberta. 2. Saskatchewan Glacier, Canada. I. Title. (Series) For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. PREFACE This report deals with principles of glacier flow that are applicable to the many glaciers in Alaska and other parts of the United States. Permission to work in Canada was extended by the Canadian Department for External Affairs, and access to the National Park was arranged by Mr. J. R. B. Coleman, then supervisor of Banff National Park. Saskatchewan Glacier was chosen for study because it is readily accessible and affords an unusually good opportunity to obtain data and develop principles that have a direct bearing on studies being made in the United States. -

Banff National Park Offers Many More Helen Katherine Backcountry Opportunities Than Those Lake Lake PARK Trail Shelters Berry River Described Here

BACKCOUNTRY CAMPGROUNDS JASPER CAMPGR OUND TOPO MAP NO . GRID REF . CAMPGR OUND TOPO MAP NO . GRID REF . WHITE GOAT NATIONAL Nigel Ba15 Wildflower Creek 82 N/8 686-003 * Lm20 Mount Costigan 82 0/3 187-783 Pass Bo1c Bow River/canoe 82 0/4 802-771 * Lm22 The Narrows 82 0/6 200-790 PARK * Br9 Big Springs 82 J/14 072-367 Lm31 Ghost Lakes 82 0/6 210-789 Sunwapta WILDERNESS AREA ◊ Br13 Marvel Lake 82 J/13 043-387 ◊ Ml22 Mystic Valley 82 0/5 886-824 Mount Pass Abraham Snowdome Lake Br14 McBride’s Camp 82 J/13 041-396 Mo5 Mosquito Creek 82 N/9 483-240 Mount Br17 Allenby Junction 82 J/13 016-414 * Mo16 Molar Creek 82 N/9 555-154 BIA Athabasca * Bw10 Brewster Creek 82 0/4 944-600 ◊ Mo18 Fish Lakes 82 N/9 556-217 NORTH * Cr6 Cascade Bridge 82 0/5 022-827 * No5 Norman Lake 83 C/2 071-706 * Cr15 Stony Creek 82 0/5 978-896 ◊ Pa8 Paradise Valley 82 N/8 528-898 * Cr31 Flints Park 82 0/5 862-958 * Re6 Lost Horse Creek 82 0/4 784-714 COLUM Glacier 93 Saskatchewan * Cr37 Block Lakes Junction 82 0/5 815-935 Re14 Shadow Lake 82 0/4 743-691 Cs Castleguard 82 C/3 857-703 * Re16 Pharaoh Creek 82 0/4 768-654 ICE FIELD Pinto Lake Mount E5 Healy Creek 82 0/4 825-608 Re21 Ball Pass Junction 82 0/4 723-652 Mount Sunset Coleman ◊ ◊ Sk5 Hidden Lake 82 N/8 626-029 Saskatchewan Pass E13 Egypt Lake 82 0/4 772-619 Ek13 Elk Lake Summit 82 0/5 951-826 ◊ Sk11 Baker Lake 82 N/8 672-049 Cs Fm10 Mount Cockscomb 82 0/4 923-766 ◊ Sk18 Merlin Meadows 82 N/9 635-093 No 5 ◊ SASKATCHEWAN 11 * Fm19 Mystic Junction 82 0/5 897-834 Sk19 Red Deer Lakes 82 N/9 667-098 River * Fm29 Sawback Lake 82 0/5 868-904 Sf Siffleur 82 N/16 441-356 Mount Gl 9 Glacier Lake 82 N/15 114-528 ◊ Sp6 Mount Rundle 82 0/4 030-647 Amery Alexandra He5 Hector Lake 82 N/9 463-144 Sp16 Rink’s Camp 82 0/4 040-555 Mount Jo9 Larry’s Camp 82 0/5 820-830 * Sp23 Eau Claire 82 J/14 067-505 Wilson * Jo18 Johnston Creek 82 0/5 771-882 * Sp35 Mount Fortune 82 J/14 123-425 ◊ Jo19 Luellen Lake 82 0/5 764-882 Su8 Howard Douglas Lake 82 0/4 880-546 Ta6 Taylor Lake 82 N/8 636-832 SASKATCHEWAN RIVER Jo29 Badger Pass Junction 82 0/5 737-932 N. -

Bergretter | Ausgabe 40 | Juni 2019 Alpinerettungschweiz INHALT 6 3 Editorial

bergretter | ausgabe 40 | juni 2019 alpinerettungschweiz INHALT 6 3 Editorial 3 Neue Datenbank GLETSCHERARCHÄOLOGIE Das eisige Archiv taut auf 4 Klimaerwärmung 6 Gletscherarchäologie 8 Fachtagung Drohnen 10 Rettung anderswo 12 Jahresbericht 2018 Personelle Wechsel 10 14 16 Kulturprojekt SAC 16 Kongress Höhlenforschung 8 BERGRETTUNG IN KANADA Schweizer Know-how in kanadischen Pärken FACHTAGUNG Wie weiter mit den Drohnen? 12 IMPRESSUM Bergretter: Magazin für Mitglieder und Partner der Alpinen Rettung Schweiz Herausgeber: Alpine Rettung Schweiz, Rega-Center, Postfach 1414, CH-8058 Zürich-Flughafen, Tel. +41 (0)44 654 38 38, Fax +41 (0)44 654 38 42, www.alpinerettung.ch, [email protected] Redaktion: Elisabeth Floh Müller, stv. Geschäftsführerin, floh.mueller@ alpinerettung.ch; Andreas Minder, [email protected] Bildnachweis: VBS/DDPS: Titelbild, S. 2, 7; zvg: S. 2, 3, 10, 11, 14, 15; Andreas Minder: S. 2, 8; ARS: S. 2, (Front Jahresbericht), 12, 13 (Grafiken); G. Jouvet, M. Huss, ETH Zürich: S. 4 (Grafik); Andreas Linsbauer, Universität Zürich: S. 5 (Grafik); Marco Cadonau: S. 6; Archäologischer Dienst des Kantons Bern: S. 6; Kantonspolizei Graubünden: S. 6; Rega: S. 9; Jean Odermatt: S. 16; Georg Taffet Crew: S 16. Auflage: 3500 Deutsch, 1000 Französisch, 800 Italienisch Adressänderungen: Alpine Rettung Schweiz, [email protected] Gesamtherstellung: Stämpfli AG, Bern Titelbild: Auf schmelzenden Gletschern tauchen Dinge wieder auf, die vor langer Zeit im Eis versunken sind. So wie das US- JAHRESBERICHT Militärflugzeug, das im Jahr 1946 auf dem Gauligletscher bruch- Mehr Einsätze als je zuvor landete (siehe Seite 7). 2 bergretter | ausgabe 40 | juni 2019 NEUE DATENBANK EDITORIAL Jetzt registrieren! Die ARS erfasst Adressen und Einsatz- tungschef Bescheid. -

Intoduction to SNOW PASS - GMC 2003

Intoduction to SNOW PASS - GMC 2003 Welcome to Snow Pass. This is the first GMC to be held at this location, and as far as we can ascertain, you are only the second group to have ever camped amongst this group of lakes. Many GMC’s are situated in valleys; however, this site is unusual as you are on the Continental Divide at an E-W “pass” between the Sullivan and Athabasca rivers, this is the arbitrary division between the Columbia Icefield to the south and the Chaba/Clemenceau Icefields to the north. But, you are also at a N-S pass between the Wales and “Watershed” glaciers, so you are at a “four way intersection” and from Base Camp you can access seven (7) different glacier systems. An intriguing local feature is the snout of the “Watershed” glacier, which actually divides so that it flows both west to join the Wales Glacier and thus drains to the Pacific and also turns east and feeds to the Arctic, which is why it is called the “Watershed” Glacier. In 2003, it may not be too obvious why in 1919 the Alberta/British Columbia Interprovincial Survey called this location “Snow Pass” but in the 1930’s (and even ? the early 1950’s) your Base Camp was still completely ice covered! There was permanent ice/snow from the “Aqueduct” to the “Watershed” to the “Toronto” Glaciers, an area of snow 5 km E-W and 10km N-S. Thus, in 1919, it really was a “snow pass”. See the appended “deglaciation” map. There is a wonderful photograph taken from the summit of Sundial peak in 1919 in the A/BC Volume, p. -

1955 Number 13

Organized 1906 Incorporated 1913 The Mountaineer Volume 48 December 28, 1955 Number 13 Editor Boa KOEHLER Dear Mountaineer, This is your Annual. You-the Tacoma Editor climbers, viewfinders, trail trippers, BRUNHILDE WISLICENUS campcra£ters, skiers, photographers -made it possible because of your extensive programs throughout Everett Editors 1955. And some of you even took KE ' CARPENTER time to report your activities and GAIL CRUMMETT to prepare articles of general in GERTRUDE SCHOCK terest. To all of you, thanks a lot. There are a number of Moun Editorial Assistant taineers who, although their names MORDA c. SLAUSO do not appear on the masthead, contributed significantly to this Climbing Adviser yearbook. They are, of course, too DICK MERRITT numerous to mention. We hope you like our idea of issu Membership Editor ing the Annual after the hustle and LORETT A SLATER bustle of tl1e holiday season has passed. Membership Committee: Winifred A. Smith, Tacoma; Violet Johnson, Everett; If your yef1r of mountaineering Marguerite Bradshaw, Elenor Buswell, has been as rewarding as ours, Ruth Hobbs, Lee Snider, typists and then we know it has indeed been proofreaders. most successful. B. K. Advertising Typist: Shirley Cox COPYRIGHT 1955 BY THE MOUNTAINEERS, Inc. (1) CONTENTS General Articles CONQUERING THE WISHBONE ARETE-by Don Claunch .... .....................·-················-··· 7 ADVENTURING IN LEBANO -by Elizabeth Johriston ····-···············-··········-·······-····· 11 MouNT RAINIER IN I DIAN LEGE TDRY-by Ella E. Clark···········-······-·····-·-·······-··- 14 SOME CLIMBS IN THE TETONS-by Maury Muzzy·····--··-····--·-··-····-···--········-- 17 Wu,TER FuN FOR THE WEn-FooTED--by Everett Lasher_···-·····-··-··-····-··········-- 18 MIDSUMMER MAD rEss- an "Uncle Dudley". editorial .......·--······· ···-····--······--···-- 21 GLACIAL ADVANCES IN THE CASCADES-by Kermit Bengston and A. -

The Mountain Life of Glen Boles Alpine Artistry the Mountain Life of Glen Boles

Alpine Artistry The Mountain Life of Glen Boles Alpine Artistry The Mountain Life of Glen Boles From anApisi test ratur aut quia que veriaectam volupta eperrum doluptat rem etur, sitatus enimi, el id quos imolor sit omnihiciae velliquas erovitius nossi rehendi cuptates niant lab intias moluptatessi ut est quunt, simi, conemoluptae voluptatiis dem dicietur? Nis sunt modit, occae sunt aliciis itatemperia quatiam facea consequid quam repudam ut lat. On pe volupta sanducid expe nesti blaborpore et, aute perovid ullaborit, quis eatibus tinctur? Tem quo omnim quo maion conesci atureriaeria nes es a susande pliquodipsum simporpora as et plabo. Namet reprendit eius evellat iasperr oriatur alignient.Ectaspis esercimus perum quod que cus autatusantur si dolupide il eosam, solupti dolorehende essi di repe conet aut anda int fugia voluptatium cullamus. Ut fuga. Nem nonsed ut odit dento etur, te omnihicae. Evenis estibus ducideris resto voluptatem cusae labores For further information regarding the Summit Series of mountaineering biographies, please contact the National Office of the Alpine Club of Canada. www.alpineclubofcanada.ca Nineteenth in the SUMMIT SERIES Biographies of people who have made a difference in Canadian mountaineering by Lynn Martel Alpine Artistry The Mountain Life of Glen Boles by Lynn Martel CANADIAN CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATIONS DATA Martel, Lynn. Alpine Artistry: The Mountain Life of Glen Boles Design by Suzan Chamney, Glacier Lily Productions. ISBN: 978-0-920330-53-1 © 2014, The Alpine Club of Canada All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be copied or reproduced without the permission of the author or the subject. The Alpine Club of Canada P.O. -

University of Alberta the Backcountry

University of Alberta The Backcountry as Home: Park Wardens, Families, and Jasper National Park’s District Cabin System, 1952-1972 by Nicole Eckert-Lyngstad A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Anthropology ©Nicole Eckert-Lyngstad Spring 2013 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Abstract This research examines home life as experienced by single and married National Park Wardens, their partners and children who resided year-round in the backcountry of Jasper National Park (JNP) between 1952 and 1972. Since the establishment of JNP in 1907, park wardens were responsible for maintaining, monitoring and patrolling large backcountry districts, and used cabins as home bases and overnight shelters. Although the district system officially ended in 1969 and no wardens have lived year-round in the backcountry since 1972, these historic cabins remain in the park and are maintained for use by current park personnel. -

Ecology & Wonder in the Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks World Heritage Site

Ecology & Wonder Ecology & Wonder in the Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks World Heritage Site Robert William Sandford Frontispiece: The © 2010 Robert W. Sandford Grand Sentinel The Grand Sentinel is a great Published by AU Press, Athabasca University stone tower located just below 1200, 10011 – 109 Street the summit of Sentinel Pass in Edmonton, AB T5J 3S8 Banff National Park. Were it located outside of the dense cluster of astounding natural Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication features contained within Canada’s mountain parks, it Sandford, Robert W. would be one of the wonders of Ecology & wonder in the Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks World Heritage the world. As it is, it is just one Site / Robert William Sandford. more landscape miracle that can be seen from the summit Includes bibliographical references and index. of the pass. Issued also in electronic format (978-1-897425-58-9). Photograph by R.W. Sandford. ISBN 978-1-897425-57-2 1. Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks World Heritage Site (Alta. and B.C.)--Environmental conditions. 2. National parks and reserves--Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks World Heritage Site (Alta. and B.C.)--Management. 3. Environmental protection--Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks World Heritage Site (Alta. and B.C.). I. Title. II. Title: Ecology and wonder. QH106.2.R6S26 2010 333.7’209712332 C2010-900473-6 Cover and book design by Virginia Penny, Interpret Design, Inc. Printed and bound in Canada by Marquis Book Printing. This publication is licensed under a Creative Commons License, Attribution- Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 2.5 Canada, see www.creativecommons.org. The text may be reproduced for non-commercial purposes, provided that credit is given to the original author. -

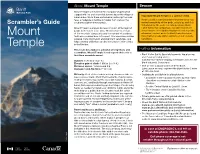

09-Atemple Bro

12. Rockfall. One of the leading causes of accidents on this Lake Climbing and Safety Tips Mount Temple and You Louise scramble route is people being struck by human-generated Difficulty: 1. Tell someone where you are going. Always leave a detailed rockfall, (see some of the Xs on the route photo). You can minimize Most of the climb is a steep, strenuous hike on loose scree Haddo or on worn, intermittent footpaths. Careful route finding minimizes Peak Sheol description of your plans with a reliable person. Include where your exposure to this hazard. Travel in a cluster with other A Climber’s Guide to your exposure to mountain hazards (rockfall, cornices, etc.) and Mount Mountain you are going, when you expect to return, your vehicle scramblers so any dislodged rocks do not gather speed and hit Aberdeen leads you through weaknesses in three cliff bands that require description, plate number and location where parked. A people below, or wait until the party is no longer directly MOUNT TEMPLE Creek climbing up short steps of rock, using your hands as needed for Voluntary Safety Registration service is available at park under/above you. Travel more slowly on descent to avoid causing Valley balance or climbing. Cairns along the route can help guide you, but information centres in Banff, Lake Louise and Field. rockfall. Tell others in your party if you see people below so you not all cairns mark the safest ascent/descent line. Route finding can be extra diligent and not cause any rockfall. Protect yourself by decisions will still be required. -

VARIOUS NOTES 117 but Evidently Not Previously Climbed

VariousNotes EDITED BY H. ADAMS CARTER UNITED STATES Tetons, Wyoming. In the past summer several new routes were made in the Tetons. A few of the more important climbs follow. Travsre between Bivouac and Rapold’s Peaks. Lying between Moran and Snowshoe Canyons is one of the most spectacularly pinnacled ridges of the Teton Range, which Leigh Ortenburger has labeled as “terrific.” After Bill Buckingham and I had reached the summit of Bivouac Peak by the ordinary route by midmorning on September 4, we started for Ray- nold’s Peak far to the west. Lying between us and our goal was a twisting, crumbling, knife-ridge, which lived up to Ortenburger’s evaluation. The actual climbing of the ridge proved not too difficult, it being clearly a problem of endurance and extreme care on the decomposed rock. Bill and I climbed all the major pinnacles, at times even rocking back and forth the summits of the smaller spires. Our greatest problem was water, and toward the end of the ridge a nearby lake was so tempting that we happily descended for refreshment. After this brief respite we took once again to the ridge and soon found ourselves on top of Raynold’s Peak. In all we took 11 hours for the traverse and all night for the return to Jackson Lake via Moran Canyon. JOHN FONDA West Ridge of the Middle Teton. The long west ridge of the Middle Teton was ascended for the first time on August 4, 1955, by William Buckingham and Mary Lou Nohr. From the south fork of Cascade Can- yon we followed a broad couloir into the lower end of the basin between the west ridges of the Grand and Middle Tetons. -

Day Hiking Lake Louise, Castle Junction and Icefields Parkway Areas

CASTLE JUNCTION AREA ICEFIELDS PARKWAY AREA LAKE LOUISE AREA PLAN AHEAD AND PREPARE Remember, you are responsible for your own safety. 1 Castle Lookout 7 Bow Summit Lookout 14 Wilcox Pass MORAINE LAKE AREA • Get advice from a Parks Canada Visitor Centre. Day Hiking 3.7 km one way; 520 m elevation gain; 3 to 4 hour round trip 2.9 km one way; 245 m elevation gain; 2.5 hour round trip 4 km one way; 335 m elevation gain; 3 to 3.5 hour round trip • Study trail descriptions and maps before starting. Trailhead: 5 km west of Castle Junction on the Bow Valley Parkway Trailhead: Highway 93 North, 40 km north of the Lake Louise junction, Trailhead: Highway 93 North, 47 km north of Saskatchewan Crossing, • Check the weather forecast and current trail conditions. Lake Louise, Castle Junction (Highway 1A). at the Peyto Lake parking lot. or 3 km south of the Icefield Centre at the entrance to the Wilcox Creek Trailheads: drive 14 km from Lake Louise along the Moraine Lake Road. • Choose a trail suitable for the least experienced member in campground in Jasper National Park. Consolation Lake Trailhead: start at the bridge near the Rockpile at your group. In the mid-20th century, Banff erected numerous fire towers From the highest point on the Icefields Parkway (2070 m), Moraine Lake. Pack adequate food, water, clothing, maps and gear. and Icefields Parkway Areas where spotters could detect flames from afar. The Castle Lookout hike beyond the Peyto Lake Viewpoint on the upper self-guided • Rise quickly above treeline to the expansive meadows of this All other trails: begin just beyond the Moraine Lake Lodge Carry a first aid kit and bear spray. -

Scrambler's Guide Mount Temple

About Mount Temple Season Mount Temple is the prominent triangular-shaped peak capped with ice and snow that towers above the village of Important! Mount Temple is a summer climb. Lake Louise. While there are technical routes up the main face, a moderate scramble is hidden from view on the Route conditions are best after the winter snow has Scrambler’s Guide southwest side of the mountain. melted completely off the peak, usually by mid-July. Unfortunately, the route can only be viewed from Mount Temple is popular because it is one of the highest Larch Valley. For comparison, consider how much peaks in the Lake Louise area. This brochure is a result snow remains on neighbouring high-elevation peaks; of the mountain’s popularity and the number of accidents otherwise, contact or visit a Banff, Lake Louise or Mount that have occurred here in the past. This brochure provides Field Parks Canada visitor centre to check on route detailed route information and important safety tips, and conditions. helps develop skills that can also be used on other climbs Temple in the Rockies. This route description is aimed at strong hikers and Further Information scramblers. Mount Temple is not a good choice for a first-time scramble ascent. • Banff Visitor Safety Specialists provide trip planning and mountaineering advice. Summit: 3 543 m (11 621 ft.) Call 403-762-1470 or drop by the Warden Office in the Elevation gain of climb: 1 690 m (5 543 ft.) Banff Industrial Compound. Distance: approx. 16 km round trip • Visit a Parks Canada visitor centre in Banff, Average round-trip time: 7-12 hours Lake Louise or Field, or phone the Banff Visitor Centre at 403-762-1550.