The Mountain Life of Glen Boles Alpine Artistry the Mountain Life of Glen Boles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploration in the Rocky Mountains North of the Yellowhead Pass Author(S): J

Exploration in the Rocky Mountains North of the Yellowhead Pass Author(s): J. Norman Collie Source: The Geographical Journal, Vol. 39, No. 3 (Mar., 1912), pp. 223-233 Published by: geographicalj Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1778435 Accessed: 12-06-2016 07:31 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wiley, The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Geographical Journal This content downloaded from 155.69.24.171 on Sun, 12 Jun 2016 07:31:04 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms EXPLORATION IN THE ROCKY MOUNTAINS. 223 overtures to Bhutan and Nepal, which have been rejected by these states, and I am very glad they have been. The Chinese should not be allowed on the Indian side of the Himalayas. The President : We will conclude with a vote of thanks to Mr. Rose for his excellent paper. EXPLORATION IN THE ROCKY MOUNTAINS NORTH OF THE YELLOWHEAD PASS.* By J. NORMAN OOLLIE, Ph.D., LL.D., F.R.S., F.R.G.S., etc. The part of the Koeky mountains, that run north through what is now the Dominion of Canada, have only in the last twenty-five years been made accessible to the ordinary traveller. -

Road Biking Guide

SUGGESTED ITINERARIES QUICK TIP: Ride your bike before 10 a.m. and after 5 p.m. to avoid traffic congestion. ARK JASPER NATIONAL P SHORT RIDES HALF DAY PYRAMID LAKE (MAP A) - Take the beautiful ride THE FALLS LOOP (MAP A) - Head south on the ROAD BIKING to Pyramid Lake with stunning views of Pyramid famous Icefields Parkway. Take a right onto the Mountain at the top. Distance: 14 km return. 93A and head for Athabasca Falls. Loop back north GUIDE Elevation gain: 100 m. onto Highway 93 and enjoy the views back home. Distance: 63 km return. Elevation gain: 210 m. WHISTLERS ROAD (MAP A) - Work up a sweat with a short but swift 8 km climb up to the base MARMOT ROAD (MAP A) - Head south on the of the Jasper Skytram. Go for a ride up the tram famous Icefields Parkway, take a right onto 93A and or just turn back and go for a quick rip down to head uphill until you reach the Marmot Road. Take a town. Distance: 16.5 km return. right up this road to the base of the ski hill then turn Elevation gain: 210 m. back and enjoy the cruise home. Distance: 38 km. Elevation gain: 603 m. FULL DAY MALIGNE ROAD (MAP A) - From town, head east on Highway 16 for the Moberly Bridge, then follow the signs for Maligne Lake Road. Gear down and get ready to roll 32 km to spectacular Maligne Lake. Once at the top, take in the view and prepare to turn back and rip home. -

North America: Physical Geography by National Geographic, Adapted by Newsela Staff on 09.22.17 Word Count 681 Level 610L

North America: Physical geography By National Geographic, adapted by Newsela staff on 09.22.17 Word Count 681 Level 610L Valley of the Ten Peaks and Moraine Lake, Banff National Park, Canada. Mountains (from left to right) Tonsa (3,057 meters), Mount Perren (3,051 m), Mount Allen (3,310 m), Mount Tuzo (3,246 m), Deltaform Mountain (3,424 m), Neptuak Mountain (3,233 m). North America is the third-largest continent. It includes Canada, the United States, and Mexico. It also includes smaller countries in Central America. Below it sits South America. North America is made up of five main areas. They are the mountainous west, the Great Plains, the Canadian Shield, the eastern region, and the Caribbean. Each area includes different types of biomes. A biome is a type of environment where plants and animals live. North America includes many biomes. It has deserts, grasslands, tundras, coral reefs, and more. Western Region North America's western region is famous for its mountains and deserts. The Rocky Mountains are found there. They are North America's largest mountain chain. The Rockies are part of a system of mountains called the Cordilleras. They include the Sierra Madre Mountains. They stretch from the southwestern United States, through Mexico, and all the This article is available at 5 reading levels at https://newsela.com. way south to Honduras. The mountains include a rare biome called a temperate rainforest. These areas get much rain. This helps them support a large mix of life forms. Black bears are found there. Some trees grow up to 300 feet tall. -

Day Hiking Lake Louise, Castle Junction and Icefields Parkway Areas

CASTLE JUNCTION AREA ICEFIELDS PARKWAY AREA LAKE LOUISE AREA PLAN AHEAD AND PREPARE Remember, you are responsible for your own safety. 1 7 14 Castle Lookout Bow Summit Lookout Wilcox Pass MORAINE LAKE AREA • Get advice from a Parks Canada Visitor Centre. Day Hiking 3.7 km one way; 520 m elevation gain; 3 to 4 hour round trip 2.9 km one way; 245 m elevation gain; 2.5 hour round trip 4 km one way; 335 m elevation gain; 3 to 3.5 hour round trip • Study trail descriptions and maps before starting. Trailhead: 5 km west of Castle Junction on the Bow Valley Parkway Trailhead: Highway 93 North, 40 km north of the Lake Louise junction, Trailhead: Highway 93 North, 47 km north of Saskatchewan Crossing, • Check the weather forecast and current trail conditions. (Highway 1A). at the Peyto Lake parking lot. or 3 km south of the Icefield Centre at the entrance to the Wilcox Creek Trailheads: drive 14 km from Lake Louise along the Moraine Lake Road. • Choose a trail suitable for the least experienced member in Lake Louise, Castle Junction campground in Jasper National Park. Consolation Lake Trailhead: start at the bridge near the Rockpile at your group. In the mid-20th century, Banff erected numerous fire towers From the highest point on the Icefields Parkway (2070 m), Moraine Lake. Pack adequate food, water, clothing, maps and gear. and Icefields Parkway Areas where spotters could detect flames from afar. The Castle Lookout hike beyond the Peyto Lake Viewpoint on the upper self-guided • Rise quickly above treeline to the expansive meadows of this All other trails: begin just beyond the Moraine Lake Lodge Carry a first aid kit and bear spray. -

Field Townsite

T HE G R E PHONE NUMBERS A T D YOHO area code (250) IV WAPTA ICEFIELD ID Amiskwi E EMERGENCY NUMBERS Pass YOHO GLACIER Gordon Ambulance 344-6226 Fire 343-6028 Des Poilus Kilometres0510 Miles R.C.M.Police 344-2221 Balfour Pass 0 5 WARDENS GLACIER (403) 762-4506 (24 hours) DES POILUS Yoho Balfour Peak OTHER NUMBERS to Jasper Yoho Information Centre 343-6783 Twin Falls Yoho National Park WAPUTIK Yoho Park Administration 343-6324 (see pages I Isolated Peak Laughing ICEFIELD C McArthur 20/21) E Falls F I Amiskwi E Daly L Yoho River River D le S Litt DALY P Niles Yoho Valley Road A GLACIER R K only open Mid-June W British A The President Takakkaw to Mid-October Y Kwetinook Pass Falls Columbia Alberta O EMERALD 5 t 4 Left-hand turns to GLACIER C Yoho Pass on the Trans-Canada Jasper re Highway are 93 ek Bosworth permitted at signed Banff Yoho Carnarvon Emerald Paget Peak intersections only. JASPER Kootenay Basin Sherbrooke Wapta Lake 1 NATIONAL Hamilton PARK Lake Ogden 2 Horsey Emerald 1A LAKE 6 LOUISE Lake Burgess Jasper Amiskwi River Field Wapta Ross to Town of Banff Pass APM Lake Lake Tocher Ridge Hamilton 3 (85 km from Falls 4 Field) and Spike Peak Narao Peak Kootenay National Emerald River Emerald 3 Park (see pages Burgess 24/25) 1 ? Stephen ALBERTA Cathedral O FIELD Cataract Brook tt er APM Lake O'Hara Fire Road BRITISH he ad BANFF R Victoria COLUMBIA i 5 Duchesnay Van Horne Range ve Abbot NATIONAL r Dennis Basin Pass PARK BANFF Duchesnay Lefroy Lake (p. -

CANADA's MOUNTAIN Rocky Mountain Goats

CANADA'S MOUNTAIN Rocky Mountain Goats CANADA'S MOUNTAIN PLAYGROUNDS BANFF • JASPER • WATERTON LAKES • YOHO KOOTENAY ° GLACIER • MOUNT REVELSTOKE The National Parks of Canada ANADA'S NATIONAL PARKS are areas The National Parks of Canada may, for C of outstanding beauty and interest that purposes of description, be grouped in three have been set apart by the Federal Govern main divisions—the scenic and recreational ment for public use. They were established parks in the mountains of Western Canada; the to maintain the primitive beauty of the land scenic, recreational, wild animals, and historic scape, to conserve the native wildlife of the parks of the Prairie Provinces; and the scenic, country, and to preserve sites of national his recreational, and historic parks of Eastern Can toric interest. As recreational areas they pro ada. In these pages will be found descriptions vide ideal surroundings for the enjoyment of of the national parks in the first group—areas outdoor life, and now rank among Canada's which lie within the great mountain regions outstanding tourist attractions. of Alberta and British Columbia. Canada's National Park system teas estab * * * lished in 1SS5, when a small area surrounding mineral hot springs at Banff in the Rocky This publication is compiled in co-operation Mountains was reserved as a public posses with the National Parks Branch, Department sion. From this beginning has been developed of Northern Affairs and National Resources. the great chain of national playgrounds note Additional information concerning these parks stretching across Canada from the Selkirk may be obtained from the Park Superintend Mountains in British Columbia to the Atlantic ents, or from the Canadian Government Travel Coast of Nova Scotia. -

22 Canada Year Book 1980-81 1.2 Principal Heights in Each Province

22 Canada Year Book 1980-81 1.2 Principal heights in each province (concluded) Province and height Elevation Province and height ALBERTA (concluded) BRITISH COLUMBIA (concluded) Mount Temple 3 544 Mount Ball 3312 Mount Lyel! 3 520 Bush Mountain 3 307 Mount Hungabee 3 520 Mount Geikie 3 305 Snow Dome 3 520 Mount Sir Alexander 3 274 Mount Kitchener 3 505 Fresnoy Mountain 3 271 Mount Athabasca 3 491 Mount Gordon 3216 Mount King Edward 3 475 Mount Stephen 3 199 Mount Brazeau 3 470 Cathedral Mountain 3 189 Mount Victoria 3 464 Odaray Mountain 3 155 Stutfield Peak 3 450 The President 3 139 Mount Joffre 3 449 Mount Laussedat 3 059 Deltaform Mountain 3 424 Mount Lefroy 3 423 YUKON Mount Alexandra 3418 St. Elias Mountains Mount Sir Douglas 3 406 Mount Woolley Mount Logan 5 951 3 405 Mount St. Elias 5 489 Lunette Peak 3 399 Mount Hector Mount Lucania 5 226 Diadem Peak 3 398 King Peak 5 173 Mount Edith Cavell 3371 Mount Steele 5 073 Mount Fryatt 3 363 Mount Wood 4 842 Mount Chown 3 361 Mount Vancouver 4 785 Mount Wilson 3 331 Mount Hubbard 4 577 Clearwater Mountain 3 261 Mount Walsh 4 505 Mount Coleman 3 176 Mount Alverstone 4439 Eiffel Peak 3 135 McArthur Peak 4 344 Pinnacle Mountain 3 079 Mount Augusta 4 289 3 067 Mount Kennedy 4 238 4212 BRITISH COLUMBIA Mount Strickland Mount Newton 4210 Vancouver island Ranges Mount Cook 4 194 Golden Hinde 2 200 Mount Craig 4 039 Mount Albert Edward 2081 Mount Malaspina 3 886 Mount Arrowsmith 1 817 Mount Badham 3 848 Coast Mountains Mount Seattle 3 073 Mount Waddington 3 994 St. -

THE COLUMBIA ICE FIELDS by A

30 CANADIAN SKI ANNUAL for the different kinds of snow which you to the end. The one who lagged behind will meet. believed that the other had some secret for I may have conveyed the impression that waxing, .but I am convinced it was simply the matter is more complicated than it that his ski were better and in better con really is in practice. My experience is that dition, so that the damp did not penetrate you cannot say, for instance, that if you and there was less strain on the wax. Also put on four layers of different wax the last he had laid a good foundation-coating so as layer will apply for the first hundred metres thoroughly to impregnate the ski. Moreover, and so on. he had certainly applied the wax on the day For a descent over varying kinds of snow before the run, rubbing it in well with his all that is necessary is to ensure that the hand. This makes an enormous difference. wax shall not be absolutely unfitted for the It is also a good thing to add a little various kinds of snow you meet, so thatyou paraffin as the last layer, especially if the do not, for instance, run into powder snow snow is wet, or if the temperatUl'e is at with fresh Klister, for in that case you will zero, or if snow is falling. This may prevent stop dead. In other words, you want a small bits of ice from forming under the ski. wax which does not directly conflict with the If you really want to wax conscientiously, quality of the snow and which will last to vou should not omit to wax the sides of the the end of the run. -

Banff National Park Offers Many More Helen Katherine Backcountry Opportunities Than Those Lake Lake PARK Trail Shelters Berry River Described Here

BACKCOUNTRY CAMPGROUNDS JASPER CAMPGR OUND TOPO MAP NO . GRID REF . CAMPGR OUND TOPO MAP NO . GRID REF . WHITE GOAT NATIONAL Nigel Ba15 Wildflower Creek 82 N/8 686-003 * Lm20 Mount Costigan 82 0/3 187-783 Pass Bo1c Bow River/canoe 82 0/4 802-771 * Lm22 The Narrows 82 0/6 200-790 PARK * Br9 Big Springs 82 J/14 072-367 Lm31 Ghost Lakes 82 0/6 210-789 Sunwapta WILDERNESS AREA ◊ Br13 Marvel Lake 82 J/13 043-387 ◊ Ml22 Mystic Valley 82 0/5 886-824 Mount Pass Abraham Snowdome Lake Br14 McBride’s Camp 82 J/13 041-396 Mo5 Mosquito Creek 82 N/9 483-240 Mount Br17 Allenby Junction 82 J/13 016-414 * Mo16 Molar Creek 82 N/9 555-154 BIA Athabasca * Bw10 Brewster Creek 82 0/4 944-600 ◊ Mo18 Fish Lakes 82 N/9 556-217 NORTH * Cr6 Cascade Bridge 82 0/5 022-827 * No5 Norman Lake 83 C/2 071-706 * Cr15 Stony Creek 82 0/5 978-896 ◊ Pa8 Paradise Valley 82 N/8 528-898 * Cr31 Flints Park 82 0/5 862-958 * Re6 Lost Horse Creek 82 0/4 784-714 COLUM Glacier 93 Saskatchewan * Cr37 Block Lakes Junction 82 0/5 815-935 Re14 Shadow Lake 82 0/4 743-691 Cs Castleguard 82 C/3 857-703 * Re16 Pharaoh Creek 82 0/4 768-654 ICE FIELD Pinto Lake Mount E5 Healy Creek 82 0/4 825-608 Re21 Ball Pass Junction 82 0/4 723-652 Mount Sunset Coleman ◊ ◊ Sk5 Hidden Lake 82 N/8 626-029 Saskatchewan Pass E13 Egypt Lake 82 0/4 772-619 Ek13 Elk Lake Summit 82 0/5 951-826 ◊ Sk11 Baker Lake 82 N/8 672-049 Cs Fm10 Mount Cockscomb 82 0/4 923-766 ◊ Sk18 Merlin Meadows 82 N/9 635-093 No 5 ◊ SASKATCHEWAN 11 * Fm19 Mystic Junction 82 0/5 897-834 Sk19 Red Deer Lakes 82 N/9 667-098 River * Fm29 Sawback Lake 82 0/5 868-904 Sf Siffleur 82 N/16 441-356 Mount Gl 9 Glacier Lake 82 N/15 114-528 ◊ Sp6 Mount Rundle 82 0/4 030-647 Amery Alexandra He5 Hector Lake 82 N/9 463-144 Sp16 Rink’s Camp 82 0/4 040-555 Mount Jo9 Larry’s Camp 82 0/5 820-830 * Sp23 Eau Claire 82 J/14 067-505 Wilson * Jo18 Johnston Creek 82 0/5 771-882 * Sp35 Mount Fortune 82 J/14 123-425 ◊ Jo19 Luellen Lake 82 0/5 764-882 Su8 Howard Douglas Lake 82 0/4 880-546 Ta6 Taylor Lake 82 N/8 636-832 SASKATCHEWAN RIVER Jo29 Badger Pass Junction 82 0/5 737-932 N. -

The Journal of the Fell & Rock Climbing Club

THE JOURNAL OF THE FELL & ROCK CLIMBING CLUB OF THE ENGLISH LAKE DISTRICT Edited by W. G. STEVENS No. 47 VOLUME XVI (No. Ill) Published bt THE FELL AND ROCK CLIMBING CLUB OF THE ENGLISH LAKE DISTRICT 1953 CONTENTS PAGE The Mount Everest Expedition of 1953 ... Peter Lloyd 215 The Days of our Youth ... ... ...Graham Wilson 217 Middle Alps for Middle Years Dorothy E. Pilley Richards 225 Birkness ... ... ... ... F. H. F. Simpson 237 Return to the Himalaya ... T. H. Tilly and /. A. ]ac\son 242 A Little More than a Walk ... ... Arthur Robinson 253 Sarmiento and So On ... ... D. H. Maling 259 Inside Information ... ... ... A. H. Griffin 269 A Pennine Farm ... ... ... ... Walter Annis 275 Bicycle Mountaineering ... ... Donald Atkinson 278 Climbs Old and New A. R. Dolphin 284 Kinlochewe, June, 1952 R. T. Wilson 293 In Memoriam ... ... ... ... ... ... 296 E. H. P. Scantlebury O. J. Slater G. S. Bower G. R. West J. C. Woodsend The Year with the Club Muriel Files 303 Annual Dinner, 1952 A. H. Griffin 307 'The President, 1952-53 ' John Hirst 310 Editor's Notes ... ... ... ... ... ... 311 Correspondence ... ... ... ... ... ... 315 London Section, 1952 316 The Library ... ... ... ... ... ... 318 Reviews ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 319 THE MOUNT EVEREST EXPEDITION OF 1953 — AN APPRECIATION Peter Lloyd Everest has been climbed and the great adventure which was started in 1921 has at last been completed. No climber can fail to have been thrilled by the event, which has now been acclaimed by the nation as a whole and honoured by the Sovereign, and to the Fell and Rock Club with its long association with Everest expeditions there is especial reason for pride and joy in the achievement. -

Draft October

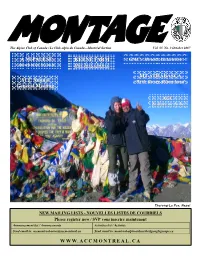

MONTAGEThe Alpine Club of Canada / Le Club Alpin du Canada—Montréal Section Vol. 65 No. 3 October 2007 A NEPALESE KEENE FARM GMC - Mount Alexandra mountain lesson Our last chance MT ATHABASCA ACC Annual With Barry Blanchard General Meeting ACC To have or to be Thorong-La Pas, Nepal NEW MAILING LISTS - NOUVELLES LISTES DE COURRIELS Please register now / SVP vous inscrire maintenant Announcement list / Annoncements Activities list / Activités Send email to: [email protected] Send email to: [email protected] WWW.ACCMONTREAL.CA IMPLIQUEZ-VOUS GET INVOLVED Faites du club ce que vous voulez qu'il soit. Make the club what you want it to be Ceci est votre chance de faire partie de l’exécutif du club! This is your chance to be part of the club’s executive Comme fait chaque année, le club ouvre toutes les positions dans As is done every year, the club is opening all positions in the exec l'exécutif pour tout membre désirant compétitionner pour ces for any member to compete for it. places. Join the exec team, it's a very fulfilling and rewarding adventure! Joignez-vous a l'équipe de l'exécutif, c'est une expérience enrichissante et valorisante. Please let us know what position you would be interested in. Positions in the executive are: SVP nous faire savoir quelle position vous intéresserait. • Chair En voici la liste: • Secretary • Président • Treasurer • Secrétaire • Membership coordinator • Trésorier • Winter house representative • Coordonnateur des membres • Keene Farm representative • Représentant du chalet -

Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) Summits on the Air

Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) Summits on the Air Canada (Alberta – VE6/VA6) Association Reference Manual (ARM) Document Reference S87.1 Issue number 2.2 Date of issue 1st August 2016 Participation start date 1st October 2012 Authorised Association Manager Walker McBryde VA6MCB Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged Page 1 of 63 Document S87.1 v2.2 Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) 1 Change Control ............................................................................................................................. 4 2 Association Reference Data ..................................................................................................... 7 2.1 Programme derivation ..................................................................................................................... 8 2.2 General information .......................................................................................................................... 8 2.3 Rights of way and access issues ..................................................................................................... 9 2.4 Maps and navigation .......................................................................................................................... 9 2.5 Safety considerations ..................................................................................................................