VARIOUS NOTES 117 but Evidently Not Previously Climbed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report on the Mountain Legacy Project

Mountain Legacy Project Report on the Mountain Legacy Project Alberta Environment and Sustainable Resources Management | April 2014 Overview The Mountain Legacy Project (MLP) is the world’s largest systematic repeat photography project. Since 2006 Alberta Environment and Sustainable Resources Development has invested in the success of this project, and this support has been decisive in digitizing and repeating more than 3,500 high resolution images along the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains, providing critical historical and change data for on-the-ground management, creating a sophisticated digital infrastructure and web services, supporting new techniques and tools for image analysis, engaging innovative research, and broadcasting to a wider public. Much more is possible. In this report, which surveys longer-term contributions but especially the funding provided by ESRD in 2012-13, we assess accomplishments and deliverables and lean forward to the next phase of work. We include a detailed overview (Appendix 1) of the repeat photography process. There are more than 10,000 historical survey images unexamined and unrepeated in Alberta. Innovative management and decision support tools can be built atop digital tools such as the custom-built ImageLabeler software and MEAT (digital inventory and web services). There is a rich opportunity for public engagement through crowdsourcing repeat images and digital and in situ exhibitions. There is certainly a book in the offing that tells the distinctive story of the mountain surveys and changes over the last century. There are multiple research projects underway that are attracting the next generation of talented graduate students. At the heart of the Mountain Legacy Project Photographs are at the heart of the Mountain Legacy Project. -

Mountain Ear MONTHLY NEWSLETTER of the ROCKY MOUNTAINEERS

Mountain Ear MONTHLY NEWSLETTER OF THE ROCKY MOUNTAINEERS wandMeetings are held on the second Wednesday of each month at 7:30 in the County Commissioner's meeting room on the second floor of the Armex (new portion) ofthe thesoula County Courthouse. Enter the building through the north door. 'Ihis month's meeting will be held on Wednesday, November 9, , i 111 Paul Jason will present a slide show entitled "Backcountry Skiing in Westem Montana, the Canadian Rockies, and the Tetons." Paul will show slides from the Bitterroots, Swans, and Mission Mountains as well as the Canadian Rockies and the Tetons, TRIPCATANTXR 11-13.. Wee day mmountainep-ing trip to 10,052-foot Mount Jackson in Glacier Park. The fmt day will be a pleasant hike/ski to Gunsight Lake where base camp will be made. ?he standard route up the peak is just a scramble, but with a heavy fresh snow cover, it should bi interesting, Other routes also exist. This will be an opportunity to experience some brisk weather in beautiful co~try.Depending on inmest and time ccmstraints,another location or a two-day trip may be substituted. Call Gerald Olbu at 549-4769 for more information, November Ski to 9351-foot St Mary's Peak in the Bitterroots near Florence, This will be a moderate ski trip, Most likely it will be possible to drive to the trailhead, so the trip will be about 4-5 miles and 2800 feet elevation gain to the peak. There is a lookout tower, open to the public, on the summit. -

Robert Wood Dissertation Final(1)

PSYCHO-SPIRITUAL TRANSFORMATION EXPERIENCED BY PARTICIPANTS OF MODERN WILDERNESS RITES OF PASSAGE QUESTS: AN INTUITIVE INQUIRY by Robert Wood A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Psychology Institute of Transpersonal Psychology Palo Alto, California March 7, 2010 I certify that I have read and approved the content and presentation of this dissertation: ________________________________________________ ____________ Nancy Rowe, Ph.D., Committee Chairperson Date ________________________________________________ ____________ Charles Fisher, Ph.D., Committee Member Date ________________________________________________ ____________ John Davis, Ph.D., Committee Member Date UMI Number: 3397618 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3397618 Copyright 2010 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 Copyright © Robert Wood 2010 All Rights Reserved ii Abstract Psycho-Spiritual Transformation Experienced by Participants of Modern Wilderness Rites of Passage Quests: An Intuitive Inquiry by Robert Wood This study investigates and reports the quest experiences of modern wilderness rites of passage questers that prompted psycho-spiritual transformation, the nature of those psycho-spiritual transformations, and the context of questers’ lives when called to quest. Intuitive Inquiry provided the method for the research that relied on the researcher’s intuitive impressions of interviews with 12 questers who believed they experienced psycho-spiritual transformation as the result of a quest. -

Getting Around Yoho National Park

2016-2017 Getting Around Yoho National Park What’s Inside • Top 10 Things to Do • Suggested Itineraries • Maps Également offert en français • Where to Camp • Safety Information P. Zizka P. Connect With Nature K. Smtih K. Smtih OUR STORY During a celebrated expedition to explore the West, Dr. James Hector travelled ahead of the group, and became the rst European to discover a steep mountain pass in 1858. After the surgeon’s trusty steed knocked him over with a blow to the chest, the spectacular route was dubbed Kicking Horse Pass. Later, the Canadian Pacic Railway, whose transcontinental route travelled through the pass, set up restaurants at the base of Mount Stephen to avoid pushing heavy dining cars up the mountain. This laid the groundwork for creating the Mount Stephen Reserve, renamed in 1901 as Yoho National Park. Eight years later, a visiting scientist, Dr. Charles Doolittle Walcott, discovered the Burgess Shale fossils on Mount Wapta. These exquisitely preserved marine organisms offer a glimpse back more than 505 million years ago. With fossils designated as part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site, 36 peaks soaring above 3 000 m, the rambunctious Kicking Horse River and numerous breathtaking waterfalls, it is no surprise Yoho was named after a Cree expression meaning “awe and wonder.” A UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE SITE Four of the mountain national parks—Banff, Jasper, Yoho and Kootenay—are recognized by the United Nations Educational, Scientic and Cultural Organization as part of the Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks World Heritage Site, for the benet and enjoyment of all nations. Among the attributes that warranted this designation were vast wilderness, diversity of ora and fauna, outstanding natural beauty and features such as Lake Louise, Maligne Lake, the Columbia Iceeld and the Burgess Shale. -

Mode of Flow of Saskatchewan Glacier Alberta, Canada

Mode of Flow of CO Saskatchewan Glacier t-t Alberta, Canada GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 351 OJ be o PQ 1960 Mode of Flow of Saskatchewan Glacier Alberta, Canada By MARK F. MEIER GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 351 Measurement and analysis of ice movement, deformation, and structural features of a typical valley glacier UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON: 1960 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRED A. SEATON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director The U.S. Geological Survey Library has catalogued this publication as follows: Meier, Mark Frederick, 1925 Mode of flow of Saskatchewan Glacier, Alberta, Canada. Washington, U.S. Govt. Print. Off., 1959. ix, 70 p. illus. (1 col.) maps, diagrs., profiles, tables. 30 cm. (U.S. Geological Survey. Professional paper 351) Part of illustrative matter folded in pocket. Measurement and analysis of ice movement, deformation, and structural features of a typical valley glacier. Bibliography: p. 67-68. 1. Glaciers Alberta. 2. Saskatchewan Glacier, Canada. I. Title. (Series) For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. PREFACE This report deals with principles of glacier flow that are applicable to the many glaciers in Alaska and other parts of the United States. Permission to work in Canada was extended by the Canadian Department for External Affairs, and access to the National Park was arranged by Mr. J. R. B. Coleman, then supervisor of Banff National Park. Saskatchewan Glacier was chosen for study because it is readily accessible and affords an unusually good opportunity to obtain data and develop principles that have a direct bearing on studies being made in the United States. -

Banff National Park Offers Many More Helen Katherine Backcountry Opportunities Than Those Lake Lake PARK Trail Shelters Berry River Described Here

BACKCOUNTRY CAMPGROUNDS JASPER CAMPGR OUND TOPO MAP NO . GRID REF . CAMPGR OUND TOPO MAP NO . GRID REF . WHITE GOAT NATIONAL Nigel Ba15 Wildflower Creek 82 N/8 686-003 * Lm20 Mount Costigan 82 0/3 187-783 Pass Bo1c Bow River/canoe 82 0/4 802-771 * Lm22 The Narrows 82 0/6 200-790 PARK * Br9 Big Springs 82 J/14 072-367 Lm31 Ghost Lakes 82 0/6 210-789 Sunwapta WILDERNESS AREA ◊ Br13 Marvel Lake 82 J/13 043-387 ◊ Ml22 Mystic Valley 82 0/5 886-824 Mount Pass Abraham Snowdome Lake Br14 McBride’s Camp 82 J/13 041-396 Mo5 Mosquito Creek 82 N/9 483-240 Mount Br17 Allenby Junction 82 J/13 016-414 * Mo16 Molar Creek 82 N/9 555-154 BIA Athabasca * Bw10 Brewster Creek 82 0/4 944-600 ◊ Mo18 Fish Lakes 82 N/9 556-217 NORTH * Cr6 Cascade Bridge 82 0/5 022-827 * No5 Norman Lake 83 C/2 071-706 * Cr15 Stony Creek 82 0/5 978-896 ◊ Pa8 Paradise Valley 82 N/8 528-898 * Cr31 Flints Park 82 0/5 862-958 * Re6 Lost Horse Creek 82 0/4 784-714 COLUM Glacier 93 Saskatchewan * Cr37 Block Lakes Junction 82 0/5 815-935 Re14 Shadow Lake 82 0/4 743-691 Cs Castleguard 82 C/3 857-703 * Re16 Pharaoh Creek 82 0/4 768-654 ICE FIELD Pinto Lake Mount E5 Healy Creek 82 0/4 825-608 Re21 Ball Pass Junction 82 0/4 723-652 Mount Sunset Coleman ◊ ◊ Sk5 Hidden Lake 82 N/8 626-029 Saskatchewan Pass E13 Egypt Lake 82 0/4 772-619 Ek13 Elk Lake Summit 82 0/5 951-826 ◊ Sk11 Baker Lake 82 N/8 672-049 Cs Fm10 Mount Cockscomb 82 0/4 923-766 ◊ Sk18 Merlin Meadows 82 N/9 635-093 No 5 ◊ SASKATCHEWAN 11 * Fm19 Mystic Junction 82 0/5 897-834 Sk19 Red Deer Lakes 82 N/9 667-098 River * Fm29 Sawback Lake 82 0/5 868-904 Sf Siffleur 82 N/16 441-356 Mount Gl 9 Glacier Lake 82 N/15 114-528 ◊ Sp6 Mount Rundle 82 0/4 030-647 Amery Alexandra He5 Hector Lake 82 N/9 463-144 Sp16 Rink’s Camp 82 0/4 040-555 Mount Jo9 Larry’s Camp 82 0/5 820-830 * Sp23 Eau Claire 82 J/14 067-505 Wilson * Jo18 Johnston Creek 82 0/5 771-882 * Sp35 Mount Fortune 82 J/14 123-425 ◊ Jo19 Luellen Lake 82 0/5 764-882 Su8 Howard Douglas Lake 82 0/4 880-546 Ta6 Taylor Lake 82 N/8 636-832 SASKATCHEWAN RIVER Jo29 Badger Pass Junction 82 0/5 737-932 N. -

Draft October

MONTAGEThe Alpine Club of Canada / Le Club Alpin du Canada—Montréal Section Vol. 65 No. 3 October 2007 A NEPALESE KEENE FARM GMC - Mount Alexandra mountain lesson Our last chance MT ATHABASCA ACC Annual With Barry Blanchard General Meeting ACC To have or to be Thorong-La Pas, Nepal NEW MAILING LISTS - NOUVELLES LISTES DE COURRIELS Please register now / SVP vous inscrire maintenant Announcement list / Annoncements Activities list / Activités Send email to: [email protected] Send email to: [email protected] WWW.ACCMONTREAL.CA IMPLIQUEZ-VOUS GET INVOLVED Faites du club ce que vous voulez qu'il soit. Make the club what you want it to be Ceci est votre chance de faire partie de l’exécutif du club! This is your chance to be part of the club’s executive Comme fait chaque année, le club ouvre toutes les positions dans As is done every year, the club is opening all positions in the exec l'exécutif pour tout membre désirant compétitionner pour ces for any member to compete for it. places. Join the exec team, it's a very fulfilling and rewarding adventure! Joignez-vous a l'équipe de l'exécutif, c'est une expérience enrichissante et valorisante. Please let us know what position you would be interested in. Positions in the executive are: SVP nous faire savoir quelle position vous intéresserait. • Chair En voici la liste: • Secretary • Président • Treasurer • Secrétaire • Membership coordinator • Trésorier • Winter house representative • Coordonnateur des membres • Keene Farm representative • Représentant du chalet -

Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) Summits on the Air

Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) Summits on the Air Canada (Alberta – VE6/VA6) Association Reference Manual (ARM) Document Reference S87.1 Issue number 2.2 Date of issue 1st August 2016 Participation start date 1st October 2012 Authorised Association Manager Walker McBryde VA6MCB Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged Page 1 of 63 Document S87.1 v2.2 Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) 1 Change Control ............................................................................................................................. 4 2 Association Reference Data ..................................................................................................... 7 2.1 Programme derivation ..................................................................................................................... 8 2.2 General information .......................................................................................................................... 8 2.3 Rights of way and access issues ..................................................................................................... 9 2.4 Maps and navigation .......................................................................................................................... 9 2.5 Safety considerations .................................................................................................................. -

Elizabeth Parker Hut

Alpine Club of Canada Backcountry Huts Elizabeth Parker Hut Index Booking, Payment and Cancellation Policy . 2 Rates . 2 Getting There . 2 Summer . 2 Winter . 2 Portering Services . 2 Trailhead location . 2 Summer approach . 2 Winter approach . 3 Summer Bus Information . 3 Maps and Guidebooks . 3 Map and GPS references . 3 Maps . 4 Guidebooks and general interest books . 4 Website Links . 4 Current conditions . 4 Area information . 4 Elizabeth Parker Hut by Nancy Hansen Parks Canada Info . 5 Wilderness Passes in National Parks . 5 Vehicle Permits . 5 Maximum Group Size . 5 Voluntary Hazardous Activities Registration . 5 What Is At the Hut . 5 Summary . 5 The buildings . 5 Sleeping arrangements . 6 Capacity . 6 Kitchen . 6 Lighting . 6 Heat . 6 Tools . 6 Drinking Water . 6 Grey Water . 6 Human Waste . 6 Garbage . 6 What You Need to Bring . 7 Hut Rules . 7 While at the hut: . 7 When leaving a hut: . 7 Things To Do Around the Hut . 8 Hiking . 8 Climbing and scrambling . 8 Backcountry Skiing . 8 Ice climbing . 8 History . 8 Page 1 Elizabeth AlpineParker ClubHut of Canada Backountry Huts Booking, Payment and Cancellation Policy Elizabeth ParkerName Hut is very popular in the summer of and therefore Hut a lottery system has been put in place . For infomation on the summer booking policies visit: http://www .alpineclubofcanada .ca/facility/ep .html#bookings View the Booking, Payment and Cancellation Policies at: www .alpineclubofcanada .ca/facility/reservations .html Rates Visit www .alpineclubofcanada .ca/facility/rates .html for current hut and wilderness pass prices . Getting There The Elizabeth Parker Hut sits at the edge of a small subalpine meadow near Lake O’Hara in Yoho National Park, amid some of the most spectacular mountain scenery in the Rockies . -

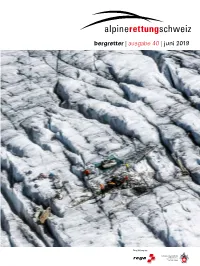

Bergretter | Ausgabe 40 | Juni 2019 Alpinerettungschweiz INHALT 6 3 Editorial

bergretter | ausgabe 40 | juni 2019 alpinerettungschweiz INHALT 6 3 Editorial 3 Neue Datenbank GLETSCHERARCHÄOLOGIE Das eisige Archiv taut auf 4 Klimaerwärmung 6 Gletscherarchäologie 8 Fachtagung Drohnen 10 Rettung anderswo 12 Jahresbericht 2018 Personelle Wechsel 10 14 16 Kulturprojekt SAC 16 Kongress Höhlenforschung 8 BERGRETTUNG IN KANADA Schweizer Know-how in kanadischen Pärken FACHTAGUNG Wie weiter mit den Drohnen? 12 IMPRESSUM Bergretter: Magazin für Mitglieder und Partner der Alpinen Rettung Schweiz Herausgeber: Alpine Rettung Schweiz, Rega-Center, Postfach 1414, CH-8058 Zürich-Flughafen, Tel. +41 (0)44 654 38 38, Fax +41 (0)44 654 38 42, www.alpinerettung.ch, [email protected] Redaktion: Elisabeth Floh Müller, stv. Geschäftsführerin, floh.mueller@ alpinerettung.ch; Andreas Minder, [email protected] Bildnachweis: VBS/DDPS: Titelbild, S. 2, 7; zvg: S. 2, 3, 10, 11, 14, 15; Andreas Minder: S. 2, 8; ARS: S. 2, (Front Jahresbericht), 12, 13 (Grafiken); G. Jouvet, M. Huss, ETH Zürich: S. 4 (Grafik); Andreas Linsbauer, Universität Zürich: S. 5 (Grafik); Marco Cadonau: S. 6; Archäologischer Dienst des Kantons Bern: S. 6; Kantonspolizei Graubünden: S. 6; Rega: S. 9; Jean Odermatt: S. 16; Georg Taffet Crew: S 16. Auflage: 3500 Deutsch, 1000 Französisch, 800 Italienisch Adressänderungen: Alpine Rettung Schweiz, [email protected] Gesamtherstellung: Stämpfli AG, Bern Titelbild: Auf schmelzenden Gletschern tauchen Dinge wieder auf, die vor langer Zeit im Eis versunken sind. So wie das US- JAHRESBERICHT Militärflugzeug, das im Jahr 1946 auf dem Gauligletscher bruch- Mehr Einsätze als je zuvor landete (siehe Seite 7). 2 bergretter | ausgabe 40 | juni 2019 NEUE DATENBANK EDITORIAL Jetzt registrieren! Die ARS erfasst Adressen und Einsatz- tungschef Bescheid. -

Intoduction to SNOW PASS - GMC 2003

Intoduction to SNOW PASS - GMC 2003 Welcome to Snow Pass. This is the first GMC to be held at this location, and as far as we can ascertain, you are only the second group to have ever camped amongst this group of lakes. Many GMC’s are situated in valleys; however, this site is unusual as you are on the Continental Divide at an E-W “pass” between the Sullivan and Athabasca rivers, this is the arbitrary division between the Columbia Icefield to the south and the Chaba/Clemenceau Icefields to the north. But, you are also at a N-S pass between the Wales and “Watershed” glaciers, so you are at a “four way intersection” and from Base Camp you can access seven (7) different glacier systems. An intriguing local feature is the snout of the “Watershed” glacier, which actually divides so that it flows both west to join the Wales Glacier and thus drains to the Pacific and also turns east and feeds to the Arctic, which is why it is called the “Watershed” Glacier. In 2003, it may not be too obvious why in 1919 the Alberta/British Columbia Interprovincial Survey called this location “Snow Pass” but in the 1930’s (and even ? the early 1950’s) your Base Camp was still completely ice covered! There was permanent ice/snow from the “Aqueduct” to the “Watershed” to the “Toronto” Glaciers, an area of snow 5 km E-W and 10km N-S. Thus, in 1919, it really was a “snow pass”. See the appended “deglaciation” map. There is a wonderful photograph taken from the summit of Sundial peak in 1919 in the A/BC Volume, p. -

Naturalist Pocket Reference

Table of Contents Naturalist Phone Numbers 1 Park info 5 Pocket GRTE Statistics 6 Reference Timeline 8 Name Origins 10 Mountains 12 Things to Do 19 Hiking Trails 20 Historic Areas 23 Wildlife Viewing 24 Visitor Centers 27 Driving Times 28 Natural History 31 Wildlife Statistics 32 Geology 36 Grand Teton Trees & Flowers 41 National Park Bears 45 revised 12/12 AM Weather, Wind Scale, Metric 46 Phone Numbers Other Emergency Avalanche Forecast 733-2664 Bridger-Teton Nat. Forest 739-5500 Dispatch 739-3301 Caribou-Targhee NF (208) 524-7500 Out of Park 911 Grand Targhee Resort 353-2300 Jackson Chamber of Comm. 733-3316 Recorded Information Jackson Fish Hatchery 733-2510 JH Airport 733-7682 Weather 739-3611 JH Mountain Resort 733-2292 Park Road Conditions 739-3682 Information Line 733-2291 Wyoming Roads 1-888-996-7623 National Elk Refuge 733-9212 511 Post Office – Jackson 733-3650 Park Road Construction 739-3614 Post Office – Moose 733-3336 Backcountry 739-3602 Post Office – Moran 543-2527 Campgrounds 739-3603 Snow King Resort 733-5200 Climbing 739-3604 St. John’s Hospital 733-3636 Elk Reduction 739-3681 Teton Co. Sheriff 733-2331 Information Packets 739-3600 Teton Science Schools 733-4765 Wyoming Game and Fish 733-2321 YELL Visitor Info. (307) 344-7381 Wyoming Highway Patrol 733-3869 YELL Roads (307) 344-2117 WYDOT Road Report 1-888-442-9090 YELL Fill Times (307) 344-2114 YELL Visitor Services 344-2107 YELL South Gate 543-2559 1 3 2 Concessions AMK Ranch 543-2463 Campgrounds - Colter Bay, Gros Ventre, Jenny Lake 543-2811 Campgrounds - Lizard Creek, Signal Mtn.