Evans, Gordon W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Faith Morgan

75 Years of Pragmatic Idealism 1940 – 2015 Arthur Morgan Institute for Community Solutions Photo courtesy of Antiochiana, Antioch College. Antioch Antiochiana, of courtesy Photo New Solutions Number 22 • Spring, 2016 CONTENTS Our Work – Susan Jennings 1 Power of Community Film 20 Philosophy of Community – Arthur Morgan 2 Passive House Revolution Film 21 Back to Yellow Springs – Scott Sanders 4 Current Program Areas of Focus 25 Fruits of Vision: 5 The Answer to Energy Poverty is Antioch Student Inspired – Ralph Keyes 5 Community Richness – Peter Bane 26 75 Years of Publications and Films 6 100 Year Plan – Jim Merkel 27 World War II Correspondence Course on Beyond Too Little Too Late – Peter Bane 28 Community – Stephanie Mills 7 Community Assessment Questions – Don Hollister 30 Mitraniketan in India – Lee Morgan 8 Life in Yellow Springs 31 Community Land Trust Pioneer – Emily Seibel 9 A Shared Adventure – Arthur Morgan 31 Ferment of the 1960’s Distilled – Don Hollister 11 Energy Navigators Program – Jonna Johnson 32 A Griscom Passion — Demurrage Economics Environmental Dashboard – Rose Hardesty 33 vs. Compound Interest – John Morgan 12 Tools for Transition – 2015 conference report 34 Jane Morgan Years and Conferences 1975 – 1997 14 Arthur Morgan Award 2015 to Stephanie Mills 36 Marianne MacQueen Reflections 15 Arthur Morgan Award 2014 – William Beale 37 The Community Journal – Krista Magaw 16 Our People, Members, and Supporters Community Solutions to Climate Change Fellows and Board 39 – 40 and Peak Oil – Don Hollister 17 Donors 41 Curtailment and Community – Pat Murphy 17 Sponsors 44 Fossil Fuels vs. Community – Megan Bachman 19 Our 63rd Conference – Charting a New Course 45 New Solutions No. -

Arthur Ernest Morgan and the Moraine Park School, 1916-1927

Arthur Ernest Morgan and the Moraine Park School, 1916-1927 Joseph Watras Beginning in 1916, Arthur E. Morgan, an engineer, and several business leaders in Dayton, Ohio created the Moraine Park School to allow students to engage in small business enterprises so they could learn how to apply academic subject matter, to be practical, to maintain industrious- ness, and to become socially responsible. With few variations, Morgan ap- plied this curriculum in schools he built as part of his efforts for labor reform while he constructed dams in Dayton. Educational reformers such as Stanwood Cobb pointed to the Mo- raine Park School as one of the first, most important progressive schools.1 Although the schools that joined the Progressive Education Association followed widely different curriculums, the founders of these schools shared concern for students’ full and free development.2 Even among these in- novative schools, Moraine Park School was unique in that the teachers helped the students start their own small businesses. The hope was that the students would increase their understanding of democracy, refine their moral qualities, and improve their entrepreneurial skills by engaging in their own profit making activities. Although this paper focuses on Morgan’s connection with Moraine Park School, this relationship was brief. In 1921, Morgan moved from Day- ton to Yellow Springs, Ohio to become president of Antioch College. About twelve years later, in 1933, he resigned the presidency of Antioch College to become chairperson of the board and chief engineer the Tennessee Val- ley Authority. He did not remain with the TVA for long. -

Florida Libraries

The information in this publication represents only a small sample of all the archival and special environment-related collections available online or at south Florida (and beyond) libraries, museums and organizations. Researchers, students and the general public should note the names of institutions possessing the original materials and contact these organizations directly for information on reproductions, copyright, research assistance, and reading room hours. I speak for the trees, for the trees have no tongues. Dr. Seuss (1904 - 1991), The Lorax Gail Donovan, Librarian, New College of Florida, Jane Bancroft Cook Library (As of February 2014, Mote’s Archivist) Mote Marine Laboratory, Arthur Vining Davis Library & Archives Susan Stover, Library & Archives Director and Erin Mahaney, Archivist Daniel Newsome and Marissa Brady, Mote Library interns Kay Hale, Mote Library volunteer We are grateful to our many library and archives colleagues throughout Florida for sharing their information and ideas. Mote Marine Laboratory Technical Report No. 1722 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 2 Trends in Environmentalism 10 a) Naturalists/Early Conservationists b) Conservationists/Preservationists c) Environmentalists Key Events in Florida’s Environmental History 14 e.g. The Swamp and Overflowed Lands Act of 1850 Great Giveaway-Reclamation Act Archival and Special Collections ….mainly print 18 Digital Collections (non-government) 73 Government Agencies (local, state, federal) 77 Plants and Herbariums 92 Facilities and Organizations 100 … whose mission -

Interview with Gordon W. Evans

Library of Congress Interview with Gordon W. Evans United States Foreign Assistance Oral History Program Foreign Assistance Oral History Collection Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training An interview with Gordon W. Evans Interviewed by Barbara S. Evans Initial interview date: December 9, 1998 Q: I am Barbara Evans, the spouse of Gordon Evans, who I will be interviewing for the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training at their request. My first question is, how did your educational background prepare you for the Foreign Service? Early years and education EVANS: My entrance into the Foreign Service was pure serendipity, but I will explain my background. It started out by growing up in western New York State with a father who was an educator and a mother who was also an educator, although she died at 43 years of age. I did my high schooling in Rochester, New York, at Monroe High for those from Rochester, a very fine public school. I went off to Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio, in 1950. It had a work-study program that was introduced by Arthur Ernest Morgan in 1920. He had retired to Yellow Springs in his 80s and was a mentor of mine. He had in early 1950 gone to India to visit President Dr. Rajendra Prasad. In fact, he was invited at his request. The Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan Commission established the Indian Institutes of Technology and also proposed the Land Grant Agricultural University involvement in India's agriculture. In Yellow Springs, in addition to a liberal arts college of about 1,200 students, there was the Fels Institute of Behavioral Studies. -

Libraries Very Internested in Sharing (LVIS) by OCLC Symbol

Libraries Very Interested In Sharing (LVIS) Listing of Members Arranged Alphabetically by OCLC Symbol * added in last 30 days A1T Coastal Pines Technical College AJR Arkansas School for Mathematics, Sciences and the Arts A2A Anne Arundel County Public Library AKC University of Central Arkansas A3E Prescott College Library AKD Central Arkansas Library System A7U American University of Sharjah AKH Henderson State University AA3 Port Townsend Public Library AKK John Brown University Library AAI Amridge University AKP Arkansas Tech University AAL Anne Arundel Community College Library AKR University of Akron AAN Albuquerque Academy AKU University of Arkansas, Little Rock AAU Air University Library AL5CW Baldwin County Library Cooperative AB0 Danbury Hospital ALGPU Alger Public Library ABF Samford University Library ALK Alaska State Library ABI Albright College ALOHA Aloha Community Library ABJ Birmingham-Jefferson Public Library ALR University of Arkansas, Little Rock - Bowen School of Law Library AC4 Ashe County Public Library ALT The University of West Alabama AC6 Lane County Library AMH Amherst College ACT Peace Corps, Information Service AML K.O. Lee Aberdeen Public Library ACY American Chemical Society AMN University of Montevallo AD# Naval Postgraduate School AMO Alamogordo Public Library AEI US Army Corps of Engineers, Mobile District AMP Mobile Public Library AEJ Enterprise State Community College ANC Antioch College AEK US Army Corps of Engineers, Rock Island District ANG Angelo State University AEU Saint Louis District ACOE Technical Library and Information Center ANM Artesia Public Library AEZ US Army Corps of Engineers, Nashville District ANO University of North Alabama AF3 US Air Force, Wright-Patterson, Fl 2300 ANTCH Antioch University Library AFB US Army Corps of Engineers, Saint Paul District Library AP5 Hanson Professional Services, Inc. -

Foundations of Modern American City Planning

FOUNDATIONS OF MODERN AMERICAN CITY PLANNING Most historians agree that modern American city planning began in the late 1800s. Some affix the date to 1893 and the Columbian Exposition in Chicago, though there is less orthodoxy regarding this moment than 15 years ago. In contrast to the earlier Colonial planning period (Philadelphia, Savannah, Williamsburg, etc.) wherein plans preceded development, planning in the 1800s generally responded to the urbanization stimulated by the industrial revolution in existing and haphazardly developing cities. The American Industrial Revolution occurred in two waves, the first in 1820-1870 and the second in 1870-1920. The U.S. grew from 7% urban in 1820 to 25% urban in 1870 and 50% urban in 1920. Three social movements categorized as precursors to modern American city planning (public health/sanitary reform, settlement house and housing reform, and parks planning) responded to the challenges and consequences of chaotic urbanization prior to modern planning's beginnings. The City Beautiful movement was a fourth response at about the same time that modern planning began. The Garden Cities Movement simultaneously commenced in England and was imported soon after. American planning grew out of and hoped to provide a broader, more comprehensive vision to these movements. Five interrelated and overlapping 1. Sanitary Reform Movement movements of the 19th Century had 2. Parks Planning/Parks Systems Movement significant effects on the first half of 3. Settlement House/Housing Reform Movement the 20th Century and helped initiate 4. Garden City Movement modern American city planning. 5. City Beautiful Movement Movement Attributes Sanitary Reform (extensive overlap An outgrowth and response to the with and sometimes referred to as accelerating urbanization of the U.S. -

Appendix: AES: Advisory Council and Board, 19Pb-194O.0

306 0Appendix: AES: Advisory Council and Board, 19pB-194O.0 The following appendix includes aIl mernbers of the AES Advisory council from 19e3 to 1935 plus all members of the Board of Directors of the Society from 1ge3 to 1940 for whom biographical data could be found, The biographies focus on elernents that relate to the individuals activities as a Ieader in the Arnerican eugenics rnovement. I have I isted membership in professional organizationE which were clearly related to eugenics such as the American Social Hygiene Association or the American Genetics Association. I have also listed other organizational affiliation where the individual served as an officer. I have also concentrated more effort on those who are less we1 I known than those who are prorninent in the historical l iterature. Thusr I have a shorter entry for Charles Davenport than for Frank Babbott. Information on Davenport is available in numerous studies of eugenicsr while very littIe is available on Frank Babbott. Inforrnation for these biographies was collected from the _p_3*o.g;sp-bJ._._.end_.._-9en_ee.l_"o-gy*j!-B-F*t3J*..Ln.C_e_x ( Pnd ed i t i on r Detroit 19AO) and the 1981-1985 cu{nulation of the Index (De,troit 19AS). Further inforrnEtion was gathered from the Eg.qgn-l-g-*1._Neglaas well as other sources. The primary source rnaterial for this appendix was originally gathered into two three ring binders. Copies of this material will be deposited with the American Philosophical Society and will be available to scholars interested in the American Eugenics Society. -

![The American Legion Monthly [Volume 16, No. 5 (May 1934)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4980/the-american-legion-monthly-volume-16-no-5-may-1934-7734980.webp)

The American Legion Monthly [Volume 16, No. 5 (May 1934)]

Night at Kinderhook By Leonard H. Nason MANHATTAN COCKTAI 1 part Italian Vermouth 3 parts Spring Garden Rye T Shake, strain and add Cherry At the fashionable places today, the Manhattan cocktail is again the cor- rect aperitif, just as it was in the days of Martin's, Sherry's and the old Beaux Arts when it was made with authentic Spring Garden Rye. Aging for you through all the slow years in charred white oak barrels, this fine whiskey now comes to you in a mel- low blend which has taken on added character and distinction. PENN-MARYLAND COMPANY, INC. 52 William St., New York Rye Back through the gen- erations, the name of SPRING GARDEN has been known and highly cherished among Rye whiskies. And now its 'f fine flavor and quality come to you in a rich blend eminently worth its price "Mine Host's Handbook," 32 pages of information about the use, traditions, and service of fine spirits, with time-honored recipes. Send 10c to Room 1219, Penn-Maryland Company, Always ask to see the bottle and look for this emblem. It signifies Inc., 52 William Street, that the whiskey on which it appears has its quality and purity New York safeguarded from the distillery to you by one watchful ownership ertisement is not intended to offer alcoholic beverages for sale or delivery in any state or community wherein the advertising, sale or use thereof is unlawful. » . WADMIMPfrfHnninu EVERY YEAR THOUSANDS ARE KILLED OR INJURED : when blow-outs throw cars out of control . HFTfTP: GET THE TIRE WITH THE PROVED 3 TIMES SAFER FROM BLOW-OUTS ANYBODY that escapes injury from a out. -

Introduction 1 Studying the Palestine Arab Refugee

N o t e s INTRODUCTION 1 . United Nations General Assembly Resolution 302 (IV) of 8 December 1949. 2 . United Nations General Assembly. Resolution 212 (III), para. 12, of 19 November 1948. 1 STUDYING THE PALESTINE ARAB REFUGEE PROBLEM 1 . For example, J. C. Hurewitz’s fundamental, The Struggle for Palestine (New York: Schocken Books, 1976), treats the questions of UNRPR and UNRWA in less than three paragraphs (see pages 321 and 326). A recent book on Palestinian refugees in Egypt only mentions UNRPR or AFSC in passing. See Oroub El-Abed, Unprotected: Palestinians in Egypt since 1948 (Washington, DC: Institute for Palestine Studies, 2009). 2. Marta Rieker, “Uses of Refugee Archives for Research and Policy Analysis. Reinterpreting the Historical Record,” in The Use of Palestinian Refugee Archives for Social Science Research and Policy Analysis , ed. S. Tamari, and E. Zureik (Jerusalem: Institute of Jerusalem Studies, 2001), 11–23. 3 . M i c h a e l R . F i s c h b a c h , Records of Dispossession: Palestinian Refugee Property and the Arab-Israeli Conflict , (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003). 4 . St é phanie L. Abdallah, “Regards, visibilit é historique et politique des images sur les r é fugié s palestiniens depuis 1948,” Le Mouvement social no. 219–220 (2007): 65–91. 5 . Channing B. Richardson, “The United Nations and Arab Refugee Relief, 1948–1950; a Case Study in International Organization and Administration” (doctoral dissertation, Columbia University, 1951). 6. Robert Simon, “Channing Richardson, Professor of International Relations (1952–1983),” Hamilton College, last accessed June 12, 2013.: www. -

Sample NHPRC Digitizing Historical Records Proposal

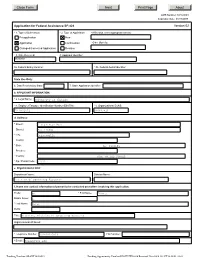

Close Form Next Print Page About OMB Number: 4040-0004 Expiration Date: 01/31/2009 Application for Federal Assistance SF-424 Version 02 * 1. Type of Submission: * 2. Type of Application: * If Revision, select appropriate letter(s): Preapplication New Application Continuation * Other (Specify) Changed/Corrected Application Revision * 3. Date Received: 4. Applicant Identifier: 05/27/2008 5a. Federal Entity Identifier: * 5b. Federal Award Identifier: State Use Only: 6. Date Received by State: 7. State Application Identifier: 8. APPLICANT INFORMATION: * a. Legal Name: University of Florida * b. Employer/Taxpayer Identification Number (EIN/TIN): * c. Organizational DUNS: 59-6002052 969663814 d. Address: * Street1: 219 Grinter Hall Street2: Box 115500 * City: Gainesville County: * State: FL: Florida Province: * Country: USA: UNITED STATES * Zip / Postal Code: 32611 e. Organizational Unit: Department Name: Division Name: Division of Sponsored Research f. Name and contact information of person to be contacted on matters involving this application: Prefix: Mr. * First Name: Thomas Middle Name: E. * Last Name: Walsh Suffix: Title: Director, Division of Sponsored Research Organizational Affiliation: * Telephone Number: 352-392-3516 Fax Number: * Email: [email protected] !"# "$ Close Form Previous Next Print Page About OMB Number: 4040-0004 Expiration Date: 01/31/2009 Application for Federal Assistance SF-424 Version 02 9. Type of Applicant 1: Select Applicant Type: H: Public/State Controlled Institution of Higher Education Type of Applicant 2: Select Applicant Type: Type of Applicant 3: Select Applicant Type: * Other (specify): * 10. Name of Federal Agency: National Archives and Records Administration 11. Catalog of Federal Domestic Assistance Number: 89.003 CFDA Title: National Historical Publications and Records Grants * 12. -

UF Historical Everglades Project Summary - 1

America's Swamp: The Historical Everglades Project Purposes and Goals of the Project: The University of Florida proposes a 3-year project that will use cost- effective methods to digitize approximately 99,690 pages in six archival collections that document the despoiling of the Everglades and the development of South Florida in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The collections selected for this project document early plans for draining the Everglades in the 1880s and 1890s, the dredging of canals and subsequent development of the destroyed wetlands at the start of the 20th century, as well as early attempts by conservationists to preserve the natural resources of the Everglades. The six Everglades collections are existing holdings of UF. All six collections will be digitized in their entirety, although a small number of boxes will be excluded because they are not within the chronological scope of the project. The collections date from 1854 to 1963, but the bulk of the materials included in this project will date from 1877 to 1929. The year 1929 was selected as an end date because it marks the end of the South Florida land boom and the onset of the Great Depression. The project will reproduce approximately 99,690 page images. Collection Extent Exclusions Pages Napoleon B. Broward Papers, 1879-1818 10.75 ln. ft. (14 11,465 boxes; 4 vol.) William Sherman Jennings Papers, 1877- 13.5 ln. ft. (29 32,575 1928 boxes; 16 vol.) May Mann Jennings Papers, 1889-1963 8 ln. ft. (23 boxes) 2 boxes dated 22,500 1930-1963 Thomas E. -

National Planning Pioneers, 1986-2015

National Planning Pioneers, 1986-2015 Charles Abrams As an international housing consultant, Charles Abrams had a major impact on housing policy after World War II. He was a longtime adviser to the United Nations and, in the 1950s, he chaired the New York State Commission Against Discrimination. In the mid-l 960s, he headed a task force that recommended consolidating New York's housing activities, a proposal that led to the creation of the New York City Housing and Development Administration. Designated a National Planning Pioneer in 1993. Frederick J. Adams Frederick J. Adams (1901-1980) founded the city and regional planning department at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1932. Adams insisted that the planning program should be interdisciplinary while also making sure that the field maintained its own identity. His students helped to create university planning programs at the University of California at Berkeley, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, Ohio State University, and Pennsylvania State University at State College. Designated a National Planning Pioneer in 1996. Thomas Adams British-born planner Thomas Adams supervised work on the 1929 Regional Plan of New York and Environs. Adams was a prolific designer of low-density residential developments that were commonly referred to as "garden suburbs." Upon returning to Great Britain, he served as one of the early presidents of the Institute of Landscape Architects, which became the Landscape Institute. Designated a National Planning Pioneer in 1989. Sherry Arnstein Sherry Arnstein became a household name among planners in 1969 when she published her ground-breaking article "A Ladder of Citizen Participation" about the hierarchy of public involvement.