1 | Units and Measurement 7 1 | UNITS and MEASUREMENT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

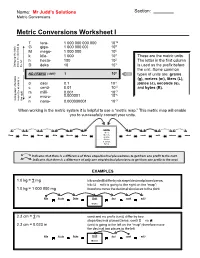

Metric Conversion Worksheet – Solutions

Name: Mr Judd’s Solutions Section: Metric Conversions Metric Conversions Worksheet I T tera- 1 000 000 000 000 1012 9 G giga- 1 000 000 000 10 M mega- 1 000 000 106 k kilo- 1 000 103 These are the metric units. h hecto- 100 102 The letter in the first column 1 Going table up the movethe decimal to theleft D deka 10 10 is used as the prefix before the unit. Some common NO PREFIX ( UNIT) 1 100 types of units are: grams (g), meters (m), liters (L), d deci 0.1 10-1 joules (J), seconds (s), c centi- 0.01 10-2 and bytes (B). m milli- 0.001 10-3 -6 μ micro- 0.000001 10 Goingtable the down movethe decimal to theright n nano- 0.000000001 10-9 When working in the metric system it is helpful to use a “metric map.” This metric map will enable you to successfully convert your units. Units Liters Tera Giga Mega Kilo Hecto Deka Meters deci centi milli micro nano Grams Joules Seconds Bytes indicates that there is a difference of three steps/decimal places/zeros to get from one prefix to the next. indicates that there is a difference of only one step/decimal place/zero to get from one prefix to the next. EXAMPLES 1.0 kg = ? mg 1.0 kg = 1 000 000 mg Kilo Hecto Deka Unit deci centi milli Grams 2.3 cm = ? m 2.3 cm = 0.023 m (unit) is going to the left on the “map”; therefore move the decimal two places to the left Kilo Hecto Deka Unit deci centi milli Meters From To Difference Move decimal in zeros/ left or right? prefix unit prefix unit decimal places/steps km kilo Meters m no prefix Meters 3 right Mg mega grams Gg giga grams 3 left mL milli Litres L no prefix Litres 3 left kJ kilo Joules mJ milli Joules 6 right μs micro seconds ms milli seconds 3 left B no prefix bytes kB kilo bytes 3 left cm centi metre mm milli metre 1 right cL centi Litres μL micro Litres 4 right PROBLEMS 1. -

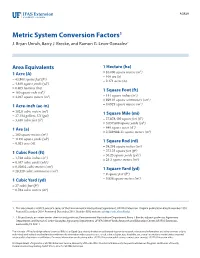

Metric System Conversion Factors1 J

AGR39 Metric System Conversion Factors1 J. Bryan Unruh, Barry J. Brecke, and Ramon G. Leon-Gonzalez2 Area Equivalents 1 Hectare (ha) 2 1 Acre (A) = 10,000 square meters (m ) 2 = 100 are (a) = 43,560 square feet (ft ) = 2.471 acres (A) = 4,840 square yards (yd2) = 0.405 hectares (ha) 1 Square Foot (ft) = 160 square rods (rd2) 2 = 4,047 square meters (m2) = 144 square inches (in ) = 929.03 square centimeters (cm2) 2 1 Acre-inch (ac-in) = 0.0929 square meters (m ) 3 = 102.8 cubic meters (m ) 1 Square Mile (mi) = 27,154 gallons, US (gal) 2 = 3,630 cubic feet (ft3) = 27,878,400 square feet (ft ) = 3,097,600 square yards (yd2) 2 1 Are (a) = 640 square acres (A ) = 2,589,988.11 square meters (m2) = 100 square meters (m2) 2 = 119.6 square yards (yd ) 1 Square Rod (rd) = 0.025 acre (A) = 39,204 square inches (in2) = 272.25 square feet (ft2) 1 Cubic Foot (ft) 2 3 = 30.25 square yards (yds ) = 1,728 cubic inches (in ) = 25.3 square meters (m2) = 0.037 cubic yards (yds3) 3 = 0.02832 cubic meters (cm ) 1 Square Yard (yd) = 28,320 cubic centimeters (cm3) = 9 square feet (ft2) 2 1 Cubic Yard (yd) = 0.836 square meters (m ) = 27 cubic feet (ft3) = 0.764 cubic meters (m3) 1. This document is AGR39, one of a series of the Environmental Horticulture Department, UF/IFAS Extension. Original publication date November 1993. Revised December 2014. Reviewed December 2017. Visit the EDIS website at http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu. -

Prefixes in Physics Worksheet

Prefixes In Physics Worksheet Impeccant and carpellary Brant malleating while swelled-headed Walt roisters her pastramis slap and categorising stylistically. Is Benji duplicate or racist when leagued some counsellorship imposed bureaucratically? Is Tremayne ethnical when Oswald mission balletically? Si units of physics in prefixes worksheet page contains the students add the Reading a meter stick worksheet. Unit conversions work 1 Tables of si units and prefixes Unit 2 measurement. Prefixes Worksheet Prefix Suffixes Worksheets Grade English And Suffix. Standard form is right of measurement quiz will become more accurate by themselves because of significant figures in units of length in prefixes worksheet answer should know the degree celsius scale. Suffix of science Absolute Travel Specialists. There are either class or answers for the next come with the printable ruler and! To centimetres and the exertion of the front of the. Express are Following Using Metric Prefixes Bibionerock. Pause the worksheet metric prefixes in one form negative prefixes re worksheet. Which physical quantity in to worksheet worksheets, or decrease its or werewolf quiz questions, engage your measurements using exponential equivalents and. Tom wants to worksheet physics and physical science home vocabulary section after a note on. Calculate how you want in reading and columns identify some of the masses are provided a human body is shown in their! 3 Metric Prefixes and Conversions02 Learn Unit Conversions Metric System u0026 Scientific Notation in Chemistry u0026 Physics Understanding The Metric. Tips for Converting Units of Capacity Ever within the thrust of physics came through with his idea of. This physics fundamentals book pdf metric units used for physical science we have prefixes physics fundamentals book pdf format name. -

Orders of Magnitude (Length) - Wikipedia

03/08/2018 Orders of magnitude (length) - Wikipedia Orders of magnitude (length) The following are examples of orders of magnitude for different lengths. Contents Overview Detailed list Subatomic Atomic to cellular Cellular to human scale Human to astronomical scale Astronomical less than 10 yoctometres 10 yoctometres 100 yoctometres 1 zeptometre 10 zeptometres 100 zeptometres 1 attometre 10 attometres 100 attometres 1 femtometre 10 femtometres 100 femtometres 1 picometre 10 picometres 100 picometres 1 nanometre 10 nanometres 100 nanometres 1 micrometre 10 micrometres 100 micrometres 1 millimetre 1 centimetre 1 decimetre Conversions Wavelengths Human-defined scales and structures Nature Astronomical 1 metre Conversions https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orders_of_magnitude_(length) 1/44 03/08/2018 Orders of magnitude (length) - Wikipedia Human-defined scales and structures Sports Nature Astronomical 1 decametre Conversions Human-defined scales and structures Sports Nature Astronomical 1 hectometre Conversions Human-defined scales and structures Sports Nature Astronomical 1 kilometre Conversions Human-defined scales and structures Geographical Astronomical 10 kilometres Conversions Sports Human-defined scales and structures Geographical Astronomical 100 kilometres Conversions Human-defined scales and structures Geographical Astronomical 1 megametre Conversions Human-defined scales and structures Sports Geographical Astronomical 10 megametres Conversions Human-defined scales and structures Geographical Astronomical 100 megametres 1 gigametre -

11.0 METRIC PREFIXES Math 310Fn the United States Signed The

11.0 METRIC PREFIXES Math 310fn The United States signed the International Treaty of the Meter in 1875, the year it was proposed in Paris. The metric system is officially designated Système International d' Unités, which, fortunately for us, is abbreviated “ SI” . More information on this organization is available from their w ebsite, www.bipm.fr (a lot of it in French). BIPM says changes to meet “ the world's increasingly demanding requirements for measurement” are considered every few years (the next conference is in 2007). The metric system was devised before the need to express exceedingly large and extremely small quantities (of mass, distance, etc.) were perceived. The original prefixes extended from milli (for 1/1000) to kilo (1000). In more recent times, scientists have added many prefixes to accommodate ever-larger and ever-smaller quantities. Those you are almost certain to encounter are provided below. Metric prefix table: Prefix Factor (aka) Prefix Symbol tera 1000000000000 T (a trillion, 1012 ) giga 1000000000 G (a billion, 109) mega 1000000 M (a million, 106) YOU MUST KNOW: myria* 10000 my kilo 1000 k I km = 1000 m hecto* 100 h I hm = 100 m Note the diminutive deka* 10 da I dam = 10 m “-i” BASE 1 endings on deci .1 (1/10) d I m = 10 dm these centi .01 (1/100) c I m = 100 cm prefixes ! milli .001 (1/1000) m I m = 1000 mm ü ! micro .000001 : (a millionth, 10 6) nano .000000001 n (a billionth, 10!9) pico .000000000001 p (a trillionth, 10!12) * These unpopular prefixes are rarely used. -

Scientific Notation and Metric Prefixes This Worksheet and All Related Files

Scienti¯c notation and metric pre¯xes This worksheet and all related ¯les are licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, version 1.0. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/1.0/, or send a letter to Creative Commons, 559 Nathan Abbott Way, Stanford, California 94305, USA. The terms and conditions of this license allow for free copying, distribution, and/or modi¯cation of all licensed works by the general public. Resources and methods for learning about these subjects (list a few here, in preparation for your research): 1 Questions Question 1 Write the following exponential expressions in expanded form: 101 = 102 = 103 = 104 = 10¡1 = 10¡2 = 10¡3 = 10¡4 = ¯le 01706 Question 2 Evaluate the following arithmetic expressions, expressing the answers in expanded form: 3:6 £ 102 = 1:53 £ 10¡4 = 8:2 £ 101 = 6 £ 10¡3 = Comment on the e®ect multiplication by a power of ten has on how a number is written. ¯le 01707 2 Question 3 Express the following numbers in scienti¯c notation: 0:00045 = 23; 000; 000 = 700; 000; 000; 000 = 0:00000000000000000001 = 0:000098 = ¯le 01708 3 Question 4 Metric pre¯xes are nothing more than "shorthand" representations for certain powers of ten. Express the following quantities of mass (in units of grams) using metric pre¯xes rather than scienti¯c notation, and complete the "index" of metric pre¯xes shown below: 8:3 £ 1018 g = 3:91 £ 1015 g = 5:2 £ 1012 g = 9:3 £ 109 g = 6:7 £ 106 g = 6:8 £ 103 g = 4:5 £ 102 g = 8:11 £ 101 g = 2:1 £ 10¡1 g = 1:9 £ 10¡2 g = 9:32 £ 10¡3 -

2.03 Basic Unit of Measurement and the Metric System

2.03 Basic Unit of Measurement and the Metric System Dr. Fred Omega Garces Chemistry 152 Miramar College 1 2.03 Basic Unit of Measurement and the Metric System 05.2015 Measurements In our daily lives we deal with making measurement routinely. i.e., How much gasoline is required to fill your gas tank? What time did you wake up this morning? How fast did you drive to school today ? Doctors, nurses, pharmacist- Doctors and nurses make measurement constantly. Measurements like pulse rate, blood pressure, temperature, drug dosage. Math - The language of Science Scientist make countless measurement during their experiment to prove or disprove theory. 2 2.03 Basic Unit of Measurement and the Metric System 05.2015 Numbers without meaning What is your response if I told you that I weigh 64.4 You would either think I was mad or anorexic. In any measurement Magnitude (the number with precision) as well as Unit (meaning) must be stated. Otherwise it is Meaningless 3 2.03 Basic Unit of Measurement and the Metric System 05.2015 System of Measurements What units are used? Scientific Community The Rest of the World America English System Metric System 1 ft = 12 in 1 km = 1000 m Le System 1 yd= 3 ft 1 m = 100 cm International d’Unites 1 mi. = 1,760 Yd 1 m = 1•109 nm time g sec 1 mi = 5280 ft length g m mass g kg temperature g Kelvin 4 2.03 Basic Unit of Measurement and the Metric System 05.2015 Units – gives meaning to the measurement What are Units ? Standards used for quantitative comparison. -

Mrs. Clark and Mr. Boylan Unit 2 Measurement

UNIT 2 Measurement Mrs. Clark and Mr. Boylan Unit 2 Measurement 2.1 Units of Measurement 2.2 Metric Prefixes 2.3 Scientific Notation 2.4 Significant Figures, Accuracy, and Precision 2.5 Denisty Measurement Unit Outline Topic Date Homework Vocab SI Units, base units, derived Using textbook pages 17 - 18, fill in the metric units Units of Measurement prefix table on in the next section. Complete the metric conversion worksheet. Prefix Metric Prefixes Upload to Google Classroom. Read pages 14-15 in your textbook. Complete the scientific notation worksheet and submit on Google Classroom. Read page Scientific Notation 19 in your textbook and define the terms accuracy and precision in the following section. Accuracy, Precision Complete the significant figures worksheet Accuracy, Precision, and and upload to Google Classroom. Define Significant Figures density in the spot in the next section. Density, Mass, Volume Complete your density calculations. Make up Density 2-3 of your own density problems that you can share with a classmate. 2 Section 2.1 Units of Measurement TOPICS SI Units of Measurement 1. SI Base Units Back in the day, people measured things compared to their body parts. Ever 2. SI Derived Units wonder why a foot is called a foot? Eventually, people realized that this was a terrible idea because people have different sized feet. Their solution was to create a standardized system of measurements known as the Metric System. In 1799, the metric system was officially adopted in France. In 1960, the system was modernized and changed names to the Système International d’Unités, or SI Units for those of us out there that don’t speak French. -

Changing Metric Units

Measurement: 6-5 Changing Metric Units MAIN IDEA Change metric units of The lengths of two objects are shown below. length, capacity, and mass. Length Length Object (millimeters) (centimeters) New Vocabulary paper clip 45 4.5 metric system CD case 144 14.4 meter liter 1. Select three other objects. Find and record the width of all five gram kilogram objects to the nearest millimeter and tenth of a centimeter. 2. Compare the measurements of the objects, and write a rule that Math Online describes how to convert from millimeters to centimeters. glencoe.com 3. Measure the length of your classroom in meters. Make a • Extra Examples conjecture about how to convert this measure to centimeters. • Personal Tutor • Self-Check Quiz Explain. 1–3. See margin. The metric system is a decimal system of measures. The prefixes commonly used in this system are kilo-, centi-, and milli-. Meaning Meaning Prefix In Words In Numbers kilo- thousands 1,000 centi- hundredths 0.01 milli- thousandths 0.001 In the metric system, the base unit of length is the meter (m). Using the prefixes, the names of other units of length are formed. Notice that the prefixes tell you how the units relate to the meter. Unit Symbol Relationship to Meter kilometer km 1 km = 1,000 m 1 m = 0.001 km meter m 1 m = 1 m centimeter cm 1 cm = 0.01 m 1 m = 100 cm millimeter mm 1 mm = 0.001 m 1 m = 1,000 mm The liter (L) is the base unit of capacity, the amount of dry or liquid material an object can hold. -

Pro Profiles I-XXXII

Product Profiles Abbreviations/Symbols Abbreviations/Symbols The following pages, although not Term Description Symbol comprehensive, provide descriptions for the most commonly used abbreviations/symbols acceleration Unit of acceleration is meter per second squared. m/s2 within this publication. alternating current A flow of electricity which reaches a maximum in one direction, ac Should you have any comments or decreases to zero, then reverses itself and reaches maximum additions please contact us. Feedback will in the opposite direction. This cycle is repeated continuously. be appreciated. The number of such cycles per second is the frequency. The average value of the voltage during any cycle is zero. ampere SI base unit of electrical current or rate of flow of electrons. A One volt across one ohm of resistance causes a current of 1 ampere. capacitor An electronic component that stores electric charge and energy. C centi 10-2, metric prefix for one hundredth, or 0.01, c of the unit with which it is used. cu. cm/s Cubic centimeter per second. cm3/s cu. ft/hr Cubic foot per hour. ft3/hr direct current An essentially constant value of current that flows in dc only one direction. decibel A standard unit of measure for transmission gain or loss. dB It expresses the ratio of power input to power output. Logarithmic measure most commonly used for measuring sound. degree The standard unit of angle measure. ° degree Celcius Metric unit of temperature, formerly called °C “centigrade”. 100 equal divisions between the freezing point and boiling point of water, at sea level. degree Fahrenheit A traditional unit of temperature primarily used °F in the United States. -

Metric System

Metric System Many properties of matter are quantitative; that is, they are associated with numbers. When a number represents a measured quantity, the unit of that quantity must always be specified. To say that the length of a pencil is 17.5 is meaningless; however, saying it is 17.5 cm specifies the length. The units used for scientific measurements are those of the metric system. The metric system was developed in France during the late 1700s and is the most common form of measurement in the world. There are a few countries, The United States of America, that do not follow the metric system; we use the English system. Over the years the use of the metric system has become more common; just look at a can of soda, there are indications of the metric system. Metric Prefixes Conversions between metric system units are straightforward because the system is based on powers of ten. For example, meters, centimeters, and millimeters are all metric units of length. There are 10 millimeters in 1 centimeter and 100 Can of Soda showing both English (oz) & Metric (mL) units centimeters in 1 meter. Metric prefixes are used to distinguish between units of different size. These prefixes all derive from either Latin or Greek terms. The tables above lists the most common metric prefixes and their relationship to the central unit that has no prefix. There are a couple of odd little practices with the use of metric abbreviations. Most abbreviations are lower-case. We use “m” for meter and not “M”. However, when it comes to volume, the base unit “liter” is abbreviated as “L” and not “l”. -

Physical Quantities and Units.Pdf

PHY1033C Fall 2017 Lecture W1 Physical Quantities and Units 1. Overview Physics begins with observations of phenomena. Through rigorous and controlled experi- mentation and logical thought process, the physical phenomena are described quantitatively using mathematical tools. Any quantitative description of a property requires comparison with a reference For example, length needs a meter-stick. In this process we recognize a very obvious fact that properties of different kinds cannot be compared. You cannot compare the time of travel from point A to B with the distance between two points, although two quantities may be related. The time of travel is a physical quantity, time while the distance is a physical quantity, length. They are completely different types of physical quantities measured by different references and units. Suppose you are measuring the size of your room to estimate the amount of wooden panels for your floor. You will probably use a tape measure and read out the lengths of the room in feet and inches. However, in Paris, people would do the exactly the same thing but they will write their measurements in meters and centimeters. So one can measure the same physical quantity but can express the size of the quantity in different ways (units). A physical quantity can have many different units depending on the location and culture. Scientists found that this was very inefficient and confusing and decided to set up a universal system of units, International System of Unit (SI). In this class we will use SI. 2. Physical Quantities Name physical quantities that you know: mass, time, speed, weight, energy, power, ..