6 Iris Clert, Guy Debord, and Asger Jorn in the Exhibition Yves Klein

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Quint : an Interdisciplinary Quarterly from the North 1

the quint : an interdisciplinary quarterly from the north 1 Editorial Advisory Board the quint volume ten issue two Moshen Ashtiany, Columbia University Ying Kong, University College of the North Brenda Austin-Smith, University of Martin Kuester, University of Marburg an interdisciplinary quarterly from Manitoba Ronald Marken, Professor Emeritus, Keith Batterbe. University of Turku University of Saskatchewan the north Donald Beecher, Carleton University Camille McCutcheon, University of South Melanie Belmore, University College of the Carolina Upstate ISSN 1920-1028 North Lorraine Meyer, Brandon University editor Gerald Bowler, Independent Scholar Ray Merlock, University of South Carolina Sue Matheson Robert Budde, University Northern British Upstate Columbia Antonia Mills, Professor Emeritus, John Butler, Independent Scholar University of Northern British Columbia David Carpenter, Professor Emeritus, Ikuko Mizunoe, Professor Emeritus, the quint welcomes submissions. See our guidelines University of Saskatchewan Kyoritsu Women’s University or contact us at: Terrence Craig, Mount Allison University Avis Mysyk, Cape Breton University the quint Lynn Echevarria, Yukon College Hisam Nakamura, Tenri University University College of the North Andrew Patrick Nelson, University of P.O. Box 3000 Erwin Erdhardt, III, University of Montana The Pas, Manitoba Cincinnati Canada R9A 1K7 Peter Falconer, University of Bristol Julie Pelletier, University of Winnipeg Vincent Pitturo, Denver University We cannot be held responsible for unsolicited Peter Geller, -

Les Nouveaux Realistes

LES NOUVEAUX REALISTES Le mouvement Nouveau Réalisme a été fondé en octobre 1960 par une déclaration commune dont les signataires sont Yves KLEIN, ARMAN, François DUFRÊNE, Raymond HAINS, Martial RAYSSE, Pierre RESTANY, Daniel SPOERRI, Jean TINGUELY, Jacques de LA VILLEGLE ; auxquels s’ajoutent CESAR, Mimmo ROTELLA, puis Niki de SAINT PHALLE et Gérard DESCHAMPS en 1961. Ces artistes affirment s’être réunis sur la base de la prise de conscience de leur «singularité collective». En effet, dans la diversité de leur langage plastique, ils perçoivent un lieu commun à leur travail, à savoir une méthode d’appropriation directe du réel, laquelle équivaut, pour reprendre les termes de Pierre RESTANY, en un « recyclage poétique du réel urbain, industriel, publicitaire» (60/90. Trente ans de Nouveau Réalisme, édition La Différence, 1990, p. 76). Leur travail collectif: des expositions élaborées ensemble, s’étend de 1960 à 1963, mais l’histoire du Nouveau Réalisme se poursuit au moins jusqu’en 1970, année du dixième anniversaire du groupe marquée par l’organisation de grandes manifestations. Pour autant, si cette prise de conscience d’une « singularité collective» est déterminante, leur regroupement se voit motivé par l’intervention et l’apport théorique du critique d’art Pierre RESTANY, lequel, d’abord intéressé par l’art abstrait, se tourne vers l’élaboration d’une esthétique sociologique après sa rencontre avec Yves KLEIN en 1958, et assume en grande partie la justification théorique du groupe. Le terme de Nouveau Réalisme a été forgé par Pierre RESTANY à l’occasion d’une première exposition collective en mai 1960. En reprenant l’appellation de « réalisme», il se réfère au mouvement artistique et littéraire né au 19e siècle qui entendait décrire, sans la magnifier, une réalité banale et quotidienne. -

Manifestopdf Cover2

A Manifesto for the Book Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden A Manifesto for the Book Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden with an edited selection of interviews, essays and case studies from the project What will be the canon for the artist’s book in the 21st Century? 1 A Manifesto for the Book Published by Impact Press at The Centre for Fine Print Research University of the West of England, Bristol February 2010 Free download from: http://www.bookarts.uwe.ac.uk/canon.htm This publication is a result of a project funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council from March 2008 - February 2010: What will be the canon for the artist’s book in the 21st Century? The AHRC funds postgraduate training and research in the arts and humanities, from archaeology and English literature to design and dance. The quality and range of research supported not only provides social and cultural benefits but also contributes to the economic success of the UK. For further information on the AHRC, please see the website www.ahrc.ac.uk ISBN 978-1-906501-04-4 © 2010 Publication, Impact Press © 2010 Images, individual artists © 2010 Texts, individual authors Editors Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden The views expressed within A Manifesto for the Book are not necessarily those of the editors or publisher. Impact Press, Centre for Fine Print Research UWE, Bristol School of Creative Arts Kennel Lodge Road, Bristol BS3 2JT United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0) 117 32 84915 Fax: +44 (0) 117 32 85865 www.bookarts.uwe.ac.uk [email protected] [email protected] 2 Contents Interview with Eriko Hirashima founder of LA LIBRERIA artists’ bookshop in Singapore 109 A Manifesto for the Book Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden 5 Interview with John Risseeuw, proprietor of his own Cabbagehead Press and Director of ASU’s Pyracantha Interview with Radoslaw Nowakowski on publishing his own Press, Arizona State University, USA 113 books and artists’ books “non-describing the world” since the 70s in Dabrowa Dolna, Poland. -

Oscar Masotta, El Helicóptero—The Helicopter, Buenos Aires, 1967

Oscar Masotta, El Helicóptero—The Helicopter, Buenos Aires, 1967. © Cloe Masotta y—and Susana Lijtmaer [Cat. 63] Publicado con motivo de la exposición Oscar Masotta. La teoría como acción (27 de abril al 13 de agosto de 2017) MUAC, Museo Universitario Arte Contem- poráneo. UNAM, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad de México. — Published on occasion of the exhibition Oscar Masotta. Theory as Action (April 27th, to August 13rd, 2017) MUAC, Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo. UNAM, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City. Textos—Texts Olivier Debroise † Manuel Hernández Ana Longoni Cloe Masotta Oscar Masotta Traducción—Translation Elizabeth Coles Brian Holmes Daniel Saldaña París Edición—Editor Ekaterina Álvarez Romero ∙ MUAC Coordinación editorial—Editorial Coordination Ana Xanic López ∙ MUAC Asistente editorial—Editorial Assistant Elena Coll Guzmán Adrián Martínez Caballero Maritere Martínez Román Corrección—Proofreading Ekaterina Álvarez Romero ∙ MUAC Elizabeth Coles Adán Delgado Ana Xanic López ∙ MUAC Martha Ordaz Diseño—Design Cristina Paoli ∙ Periferia Asistente de formación—Layout Assistant Krystal Mejía Primera edición 2017—First edition 2017 D.R. © MUAC, Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo, UNAM, Insurgentes Sur 3000, Centro Cultural Universitario, C.P. 04510, Ciudad de México D.R. © de los textos, sus autores—the authors for the texts D.R. © de la traducción, sus autores—the translators for the translations D.R. © de las imágenes, sus autores—the authors for the images © 2017, Editorial RM, S.A. de C. V., Río Pánuco 141, colonia Cuauhtémoc, 06500, Ciudad de México © RM Verlag S.L.C/Loreto 13-15 Local B, 08029, Barcelona, España www.editorialrm.com #319 ISBN RM Verlag 978-84-17047-16-0 ISBN 978-607-02-9244-6 Todos los derechos reservados. -

Film Farbe Fläche. Ästhetik Des Kolorierten Bildes Im Kino 1895–1930

Jelena Rakin Jelena Rakin Die nachträgliche Kolorierung des schwarzweißen Film Farbe Fläche Materials war in der Stummfilmepoche eine verbrei- tete Praxis. Die Filme wurden hand- oder schablo- Ästhetik des kolorierten Bildes nenkoloriert, viragiert und getont. Die häufig osten- tativ ausgestellte Materialität der aufgetragenen im Kino 1895–1930 Farbe stand in einem Spannungsverhältnis zum fotografischen Bild und bewirkte eine spezifische Dynamik zwischen dem Eindruck von Flächigkeit und Plastizität. Kolorierungen kamen in Serpen- tinentanzfilmen, den ornamentalen Motiven der Féerien, in Trickfilmen oder Moderevuen besonders zur Geltung. In dieser Hinsicht weisen die applika- tiven Farbtechniken des Films viele Parallelen zu anderen farbigen Bildmedien der Epoche auf (wie Gebrauchsgrafik oder Modeillustration). Zudem zeigt der kolorierte Film seine Nähe zur industriali- sierten Ästhetik, vornehmlich zur visuellen Form kommerzieller Farbpaletten. In dieser Studie wird die farbige Fläche des kolorier- ten Films im Kontext einer intermedialen Geschichte des Ästhetischen untersucht. Farbe als Attraktion, Film Farbe Fläche ostentative Materialität und Element medialer Selbstreflexion der Kunst tritt aus dieser Perspek- tive als eine Sinnfigur der chromatischen Moderne und der populären visuellen Kultur des frühen 20. Jahrhunderts hervor. Jelena Rakin ist Oberassistentin am Seminar für Filmwissenschaft in Zürich, wo sie an einer Ha bilitationsschrift zur Ästhetik von Kosmos- bildern arbeitet. ISBN 978-3-7410-0344-8 ZÜRCHER FILMSTUDIEN 44 Jelena Rakin Film Farbe Fläche ZÜRCHER FILMSTUDIEN BEGRÜNDET VON CHRISTINE N. BRINCKMANN HERAUSGEGEBEN VON JÖRG SCHWEINITZ UND MARGRIT TRÖHLER BAND 44 JELENA RAKIN FILM FARBE FLÄCHE Ästhetik des kolorierten Bildes im Kino 1895–1930 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. -

Transformatio Energetica Hermetische Kunst Im 20. Jahrhundert

Transformatio energetica Hermetische Kunst im 20. Jahrhundert Von der Repräsentation zur Gegenwart der Hermetik im Werk von Antonin Artaud, Yves Klein und Sigmar Polke Von der Philosophisch-Historischen Fakultät der Universität Stuttgart zur Erlangung der Würde eines Doktors der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) genehmigte Abhandlung vorgelegt von Ulrike Seegers aus Münster / Westf. Hauptberichter: Prof. Dr. Beat Wyss Mitberichter: Prof. Dr. Stefan Majetschak Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 16. Januar 2002 Institut für Kunstgeschichte der Universität Stuttgart 2003 ,1+$/769(5=(,&+1,6 ZUSAMMENFASSUNG..........................................................................................................7 SYNOPSIS............................................................................................................................9 ,0$7(5,$35,0$ *HJHQVWDQG Einleitung: Hermes Trismegistos als kunstwissenschaftlicher Parameter?..................11 ,,1,*5('2 $QDO\VH 'LH+HUPHWLN 1. Begriffliche Annäherung........................................................................................17 2. Entstehungshintergründe und Inhalte.....................................................................20 2.1 Thoth + Hermes = Hermes Trismegistos.......................................................... 20 2.2 Textquellen........................................................................................................25 2.2.1 Corpus Hermeticum...............................................................................26 2.2.1.1 Die griechischen -

Gazette Drouot INTERNATIONAL

Gazette Drouot INTERNATIONAL NUMBER 13 UPDATE CLICK HERE TO FIND THE LATEST NEWS W thExhibition ANTIBES ArtFAIR Antiques Modern Art PORT VAUBAN 7TH TO 23RD APRIL 2012 10.30 A.M. TO 7.30 P.M. www.dpi-design.fr INFOS : O4 93 34 8O 82 - O4 93 34 65 65 WWW.SALON-ANTIQUAIRES-ANTIBES.COM ORGANIZED BY THE ACAAFVA UNDER THE HONORARY PRESIDENCY OF THE ANTIBES JUAN-LES-PINS MAYOR. THE MAGAZINE CONTENTS CONTENTS ART MARKET - MAGAZINE UPCOMING 8 “The Scream” by Edvard Munch, one of the most emblematic pictures of the 20th century, in the forthcoming sale in New York. In Paris, many sales will be dedicated to classic art, a superb illuminated manuscript from the collection of publisher Hachette, the Niel Collection with 18th century furniture. The Jourdan-Barry Collection presents its goldsmith treasures. Last but not least, the Borghese collection… 82 DESIGN Mid-century American and above all California Design is popular. It inspires contemporary designers; its vintage items are fetching higher and higher prices, and the copy industry is flourishing. 46 RESULTS 90 ART FAIRS The Parisian sales celebrated paintings, Rodolphe Janssen, a world-renowned Brussels especially those of the old masters, like Agnolo gallery owner and a member of the Brussels Fair's Gaddi and Etienne Aubry, as well as the more selection committee, told us about the 2012 show, modern Leopold Survage… Classical furniture, which will take place from 19 to 22 April. pre-Colombian Art and manucripts are doing well. In New York, the sale of the Shoshana Collection was a success with a world record for an ancient Judaean coin. -

Le Ciel Comme Atelier, Yves Klein Et Ses Contemporains

LE CIEL COMME ATELIER YVES KLEIN ET SES CONTEMPORAINS 18.07.2020 > 01.02.2021 LE CIEL COMME ATELIER / DOSSIER DÉCOUVERTE SOMMAIRE 1. PRÉSENTATION DE L’EXPOSITION P.3 2. YVES KLEIN ET SES CONTEMPORAINS P.5 3. SE SITUER P.7 4. LE PARCOURS DE L’EXPOSITION P.8 5. LISTE DES ARTISTES PRÉSENTÉS P.19 6. MOTS EN LIBERTÉ P.20 7. JEUNE PUBLIC P.29 8. INFORMATIONS PRATIQUES P.30 En couverture : Charles Wilp, Yves Klein travaillant à l’Opéra-Théâtre de Gelsenkirchen, 1958 - Version PRINT Photographie © Charles Wilp / BPK, Berlin © Succession Yves Klein c/o Adagp, Paris, 2020 2 LE CIEL COMME ATELIER / DOSSIER DÉCOUVERTE 1. PRÉSENTATION DE L’EXPOSITION Du 18 juillet 2020 au 01 février 2021 GRANDE NEF Le Centre Pompidou-Metz présente à partir du 18 juillet 2020 une exposition consacrée à Yves Klein (1928-1962), figure majeure de la scène artistique française et européenne d’après-guerre. Au-delà de la mouvance des Nouveaux Réalistes à laquelle la critique, à la suite de Pierre Restany, l’a principalement rattaché, Yves Klein a développé des liens intenses avec une constellation d’artistes, des spatialistes en Italie aux groupes ZERO et Nul en Allemagne et aux Pays-Bas. Il a également entretenu des affinités certaines avec le groupe Gutaï au Japon. À leurs côtés, Yves Klein, « peintre de l’espace », fait entrer l’art dans une nouvelle dimension où le ciel, l’air, le vide et le cosmos figurent un atelier immatériel propice à réinventer le rapport de l’homme au monde, après la tabula rasa de la guerre. -

Yves Klein : La Majorité Posthume

Yves Klein 3 mars/ 23 mai Musée national d'art moderne Yves Klein : la majorité posthume «Ne posez pas de questions. On ne vous mentira pas.» Elizabeth Bowen. Yves Klein est né en 1928, il est mort visuellement autre ou des actes — qui prématurément en 1962 . La presque ne sont pas encore des happenings — totalité de son oeuvre appartient aux mais lui apparaissent comme une années cinquante, elle commence la preuve de forfanterie infantile et le deuxième moitié du xxe siècle. laissent sans mots, sans attirance, et dédaigneux L'adolescence, la jeunesse de Klein, . Pourtant, Klein né à Nice, est méditerranéen et aussi français que c'est l'École de Paris, l'abstraction géo- Paul Valéry — et c'est extraordinaire métrique, l'art informel ou l'art brut et comme on peut passer des poésies et «l'engagement» . Tout de suite son des textes de l'un à la peinture et même oeuvre s'écarte de ce climat, de ses aux écrits de l'autre, sans changer facilités, de ses contraintes . Elle est d'esprit ou de registre. L'oeuvre de Klein radicale par rapport à l'époque et sera sera solaire, lumineuse — classique, perçue dès les années soixante en équilibrée, parfaitement définie, visuel- France et dans le monde comme une lement, dans son déroulement rapide, ouverture, sur l'art conceptuel et ulté- ses moments successifs et par aussi les rieurement par une fraction du public et nombreux écrits qu'il a laissés et la des artistes comme une préfiguration prolongent mieux que tout autre et nous d'un certain retour, une réintroduction entretiennent des projets qui nous sem- de la forme humaine dans la peinture. -

0280.1.00.Pdf

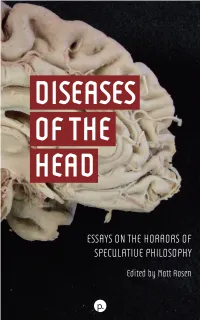

diseases of the head Before you start to read this book, take this moment to think about making a donation to punctum books, an independent non-profit press, @ https://punctumbooks.com/support/ If you’re reading the e-book, you can click on the image below to go directly to our donations site. Any amount, no matter the size, is appreciated and will help us to keep our ship of fools afloat. Contri- butions from dedicated readers will also help us to keep our commons open and to cultivate new work that can’t find a welcoming port elsewhere. Our ad- venture is not possible without your support. Vive la Open Access. Fig. 1. Hieronymus Bosch, Ship of Fools (1490–1500) diseases of the head: essays on the horrors of speculative philoso- phy. Copyright © 2020 by the editors and authors. This work carries a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license, which means that you are free to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format, and you may also remix, transform and build upon the material, as long as you clearly attribute the work to the authors (but not in a way that suggests the authors or punctum books endorses you and your work), you do not use this work for commercial gain in any form whatsoever, and that for any remixing and transformation, you distribute your rebuild under the same license. http://creativecommons.org/li- censes/by-nc-sa/4.0/ First published in 2020 by punctum books, Earth, Milky Way. https://punctumbooks.com ISBN-13: 978-1-953035-10-3 (print) ISBN-13: 978-1-953035-11-0 (ePDF) doi: 10.21983/P3.0280.1.00 lccn: 2020945732 Library of Congress Cataloging Data is available from the Library of Congress Copy editing: Lily Brewer Book Design: Vincent W.J. -

Yves Klein (1928-1962)

YVES KLEIN (1928-1962) Yves Klein est un artiste français célèbre pour son invention de l’IKB (International Klein Blue). De ses monochromes aux anthropométries en passant par l’emploi du feu et de l’or, Yves Klein a conçu des œuvres qui traversent les frontières de l’art conceptuel et de la performance. BIOGRAPHIE JEUNESSE DE L’ARTISTE YVES KLEIN Yves Klein rencontre Marcel Barillon de Murat, chevalier Yves Klein naît en 1928 à Nice de deux parents artistes : de l’ordre des Archers de Saint-Sébastien à la Galerie Fred Klein et Marie Raymond, lui peintre figuratif et elle Allendy, qui l’invite à rejoindre la Confrérie. Le 11 mars 1956, peintre abstraite. La famille fait des allers-retours entre à l’église Saint-Nicolas-des-Champs à Paris, Yves Klein est Paris et Nice. Très jeune, Yves Klein commence à travailler fait chevalier. Il choisit la devise : « Pour la couleur ! Contre dans la librairie de sa tante Rose Raymond à Nice. Il la ligne et le dessin ! ». rencontre le futur artiste Arman et le poète Claude Pascal dans son club de judo. C’est en 1957 qu’Yves Klein crée son iconique IKB Les parents de Yves Klein fréquentent l’artiste Nicolas de (International Klein Blue) qui caractérise son « Époque Staël et sa compagne Jeannine Guillou, ainsi que le fils de Bleu » jusqu’en 1959. Yves Klein présente ces œuvres d’art celle-ci : Antek qui devient un ami d’Yves Klein. La famille pour la première fois à l’exposition : Yves Klein, Proposte Klein rencontre également les artistes du Groupe de monocrome, epoca blu à la Galerie Apollinaire à Milan, en Grasse : Alberto Magnelli, Jean Arp, Sophie Taeuber, Sonia janvier 1957. -

![Publier]…[Exposer](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0369/publier-exposer-5040369.webp)

Publier]…[Exposer

PUBLIER]…[EXPOSER Les pratiques éditoriales et la question de l’exposition 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 PUBLIER]…[EXPOSER 1 1 1 1 1 1 Les pratiques éditoriales et la question de l’exposition 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 sous la direction de clémentine mélois 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 3 1 1 1 1 anne mœglin-delcrOIX publier]…[exposer 1 1 1 1 1 1 2011-2012 3 3 1 1 2 ÉCOLE SUPÉRIEURE DES BEAUX-ARTS DE NÎMES 3 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 Clémentine Mélois Introduction 6 Anne Mœglin-Delcroix Le livre d’artiste et la question de l’exposition 13 Jérôme Dupeyrat Publier et exposer – Exposer et publier 31 Éric Watier Copier n’est pas voler 49 Monotone Lab (Éric Watier) 63 Françoise Lonardoni Objets de vitrine et de curiosité 81 Stéphane Le Mercier Sans titre, tout support 93 Leszek Brogowski Le livre d’artiste et le discours de l’exposition 107 Roberto Martinez Révolution(s) 133 Clémentine Mélois Multiple territoire 151 Laura Safred L’exposition du livre d’artiste : point d’intersection entre langage typographique et numérique 161 Guy Dugas Littérature publiée, littérature exposée 169 Les débats 179 sommaire Les auteurs 191 5 3 5 Clémentine Mélois publier]…[exposer : introduction c Cet ouvrage regroupe les puyant sur sa définition, nous avons choisi tels que le Pop Art, la poésie visuelle, œuvres ont l’apparence d’éditions que textes des intervenants du de consacrer ce colloque au livre d’artiste.