Provisional Realities Live Art 1951-2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Quint : an Interdisciplinary Quarterly from the North 1

the quint : an interdisciplinary quarterly from the north 1 Editorial Advisory Board the quint volume ten issue two Moshen Ashtiany, Columbia University Ying Kong, University College of the North Brenda Austin-Smith, University of Martin Kuester, University of Marburg an interdisciplinary quarterly from Manitoba Ronald Marken, Professor Emeritus, Keith Batterbe. University of Turku University of Saskatchewan the north Donald Beecher, Carleton University Camille McCutcheon, University of South Melanie Belmore, University College of the Carolina Upstate ISSN 1920-1028 North Lorraine Meyer, Brandon University editor Gerald Bowler, Independent Scholar Ray Merlock, University of South Carolina Sue Matheson Robert Budde, University Northern British Upstate Columbia Antonia Mills, Professor Emeritus, John Butler, Independent Scholar University of Northern British Columbia David Carpenter, Professor Emeritus, Ikuko Mizunoe, Professor Emeritus, the quint welcomes submissions. See our guidelines University of Saskatchewan Kyoritsu Women’s University or contact us at: Terrence Craig, Mount Allison University Avis Mysyk, Cape Breton University the quint Lynn Echevarria, Yukon College Hisam Nakamura, Tenri University University College of the North Andrew Patrick Nelson, University of P.O. Box 3000 Erwin Erdhardt, III, University of Montana The Pas, Manitoba Cincinnati Canada R9A 1K7 Peter Falconer, University of Bristol Julie Pelletier, University of Winnipeg Vincent Pitturo, Denver University We cannot be held responsible for unsolicited Peter Geller, -

Download the Programme As A

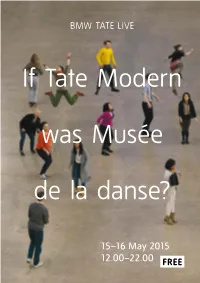

Introduction 15–16 May 2015 12.00–22.00 FREE #dancingmuseum Map Introduction BMW TATE LIVE: If Tate Modern was Musée de la danse? Tate Modern Friday 15 May and Saturday 16 May 2015 12.00–22.00 FREE Starting with a question – If Tate Modern was Musée de la danse? Restaurant – this project proposes a fictional transformation of the art museum 6 via the prism of dance. A major new collaboration between Tate Modern and the Musée de la danse in Rennes, France, directed by Members Room dancer and choreographer Boris Charmatz, this temporary 5 occupation, lasting just 48 hours, extends beyond simply inviting the 20 Dancers discipline of dance into the art museum. Instead it considers how the 4 museum can be transformed by dance altogether as one institution 20 Dancers overlaps with another. By entering the public spaces and galleries of 3 Tate Modern, Musée de la danse dramatises questions about how art might be perceived, displayed and shared from a danced and 20 Dancers expo zéro choreographed perspective. Charmatz likens the scenario to trying on 2 a new pair of glasses with lenses that opens up your perception to River Café forms of found choreography happening everywhere. Entrance 1 Shop Shop Turbine Hall Presentations of Charmatz’s work are interwoven with dance À bras-le-corps 0 to manger 0performances that directly involve viewers. Musée de la danse’s Main regular workshop format, Adrénaline – a dance floor that is open Entrance to everyone – is staged as a temporary nightclub. The Turbine Hall oscillates between dance lesson and performance, set-up and take-down, participation and party. -

Les Nouveaux Realistes

LES NOUVEAUX REALISTES Le mouvement Nouveau Réalisme a été fondé en octobre 1960 par une déclaration commune dont les signataires sont Yves KLEIN, ARMAN, François DUFRÊNE, Raymond HAINS, Martial RAYSSE, Pierre RESTANY, Daniel SPOERRI, Jean TINGUELY, Jacques de LA VILLEGLE ; auxquels s’ajoutent CESAR, Mimmo ROTELLA, puis Niki de SAINT PHALLE et Gérard DESCHAMPS en 1961. Ces artistes affirment s’être réunis sur la base de la prise de conscience de leur «singularité collective». En effet, dans la diversité de leur langage plastique, ils perçoivent un lieu commun à leur travail, à savoir une méthode d’appropriation directe du réel, laquelle équivaut, pour reprendre les termes de Pierre RESTANY, en un « recyclage poétique du réel urbain, industriel, publicitaire» (60/90. Trente ans de Nouveau Réalisme, édition La Différence, 1990, p. 76). Leur travail collectif: des expositions élaborées ensemble, s’étend de 1960 à 1963, mais l’histoire du Nouveau Réalisme se poursuit au moins jusqu’en 1970, année du dixième anniversaire du groupe marquée par l’organisation de grandes manifestations. Pour autant, si cette prise de conscience d’une « singularité collective» est déterminante, leur regroupement se voit motivé par l’intervention et l’apport théorique du critique d’art Pierre RESTANY, lequel, d’abord intéressé par l’art abstrait, se tourne vers l’élaboration d’une esthétique sociologique après sa rencontre avec Yves KLEIN en 1958, et assume en grande partie la justification théorique du groupe. Le terme de Nouveau Réalisme a été forgé par Pierre RESTANY à l’occasion d’une première exposition collective en mai 1960. En reprenant l’appellation de « réalisme», il se réfère au mouvement artistique et littéraire né au 19e siècle qui entendait décrire, sans la magnifier, une réalité banale et quotidienne. -

Manifestopdf Cover2

A Manifesto for the Book Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden A Manifesto for the Book Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden with an edited selection of interviews, essays and case studies from the project What will be the canon for the artist’s book in the 21st Century? 1 A Manifesto for the Book Published by Impact Press at The Centre for Fine Print Research University of the West of England, Bristol February 2010 Free download from: http://www.bookarts.uwe.ac.uk/canon.htm This publication is a result of a project funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council from March 2008 - February 2010: What will be the canon for the artist’s book in the 21st Century? The AHRC funds postgraduate training and research in the arts and humanities, from archaeology and English literature to design and dance. The quality and range of research supported not only provides social and cultural benefits but also contributes to the economic success of the UK. For further information on the AHRC, please see the website www.ahrc.ac.uk ISBN 978-1-906501-04-4 © 2010 Publication, Impact Press © 2010 Images, individual artists © 2010 Texts, individual authors Editors Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden The views expressed within A Manifesto for the Book are not necessarily those of the editors or publisher. Impact Press, Centre for Fine Print Research UWE, Bristol School of Creative Arts Kennel Lodge Road, Bristol BS3 2JT United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0) 117 32 84915 Fax: +44 (0) 117 32 85865 www.bookarts.uwe.ac.uk [email protected] [email protected] 2 Contents Interview with Eriko Hirashima founder of LA LIBRERIA artists’ bookshop in Singapore 109 A Manifesto for the Book Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden 5 Interview with John Risseeuw, proprietor of his own Cabbagehead Press and Director of ASU’s Pyracantha Interview with Radoslaw Nowakowski on publishing his own Press, Arizona State University, USA 113 books and artists’ books “non-describing the world” since the 70s in Dabrowa Dolna, Poland. -

Oscar Masotta, El Helicóptero—The Helicopter, Buenos Aires, 1967

Oscar Masotta, El Helicóptero—The Helicopter, Buenos Aires, 1967. © Cloe Masotta y—and Susana Lijtmaer [Cat. 63] Publicado con motivo de la exposición Oscar Masotta. La teoría como acción (27 de abril al 13 de agosto de 2017) MUAC, Museo Universitario Arte Contem- poráneo. UNAM, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad de México. — Published on occasion of the exhibition Oscar Masotta. Theory as Action (April 27th, to August 13rd, 2017) MUAC, Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo. UNAM, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City. Textos—Texts Olivier Debroise † Manuel Hernández Ana Longoni Cloe Masotta Oscar Masotta Traducción—Translation Elizabeth Coles Brian Holmes Daniel Saldaña París Edición—Editor Ekaterina Álvarez Romero ∙ MUAC Coordinación editorial—Editorial Coordination Ana Xanic López ∙ MUAC Asistente editorial—Editorial Assistant Elena Coll Guzmán Adrián Martínez Caballero Maritere Martínez Román Corrección—Proofreading Ekaterina Álvarez Romero ∙ MUAC Elizabeth Coles Adán Delgado Ana Xanic López ∙ MUAC Martha Ordaz Diseño—Design Cristina Paoli ∙ Periferia Asistente de formación—Layout Assistant Krystal Mejía Primera edición 2017—First edition 2017 D.R. © MUAC, Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo, UNAM, Insurgentes Sur 3000, Centro Cultural Universitario, C.P. 04510, Ciudad de México D.R. © de los textos, sus autores—the authors for the texts D.R. © de la traducción, sus autores—the translators for the translations D.R. © de las imágenes, sus autores—the authors for the images © 2017, Editorial RM, S.A. de C. V., Río Pánuco 141, colonia Cuauhtémoc, 06500, Ciudad de México © RM Verlag S.L.C/Loreto 13-15 Local B, 08029, Barcelona, España www.editorialrm.com #319 ISBN RM Verlag 978-84-17047-16-0 ISBN 978-607-02-9244-6 Todos los derechos reservados. -

Music and the Figurative Arts in the Twentieth Century

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE MUSIC AND FIGURATIVE ARTS IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY 14-16 November 2014 Lucca, Complesso Monumentale di San Micheletto PROGRAMME ORGANIZED BY UNDER THE AUSPICES OF CENTRO STUDI OPERA OMNIA LUIGI BOCCHERINI www.luigiboccherini.org MUSIC AND FIGURATIVE ARTS IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY International Conference 14-16 November 2014 Lucca, Complesso monumentale di San Micheletto Organized by Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini, Lucca Under the auspices of Province of Lucca ef SCIENTIFIC COmmITEE Germán Gan Quesada (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona) Roberto Illiano (Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini) Massimiliano Locanto (Università degli Studi di Salerno) Fulvia Morabito (Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini) Luca Lévi Sala (Université de Poitiers) Massimiliano Sala (Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini) ef KEYNOTE SPEAKERS Björn R. Tammen (Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften | Institut für kunst- und musikhistorische Forschungen) INVITED SPEAKERS Germán Gan Quesada (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona) Luca Lévi Sala (Université de Poitiers) Gianfranco Vinay (Université de Paris 8) FRIDAY 14 NOVEMBER 8.30-9.30: Welcome and Registration Room 1: 9.30-9.45: Opening • MASSIMILIANO SALA (President Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini) Room 1 Italian Music and Figurative Arts until the 40s 10.00-10.45 • Luca Lévi Sala (Université de Poitiers): «Liberaci dalla cultura»: Autarchia fascista tra musica e immagini. Purificazione culturale e antisemitismo ne «Il Tevere» (1933-1938) 11.15-12.45 (Chair: Luca Lévi Sala, Université de Poitiers) • Colin J. P. Homiski (Senate House Library, University of London): Aeromusica, Azione, and Automata: New Images of Futurist Sound • Valentina Massetti (Università Ca’ Foscari, Venezia): «Balli Plastici»: Casella e il Teatro futurista di Depero • Olga Jesurum (Università degli studi di Roma ‘La Sapienza’): Il “rinnovamenteo musicale italiano” fra le due guerre. -

ZERO ERA Mack and His Artist Friends

PRESS RELEASE: for immediate publication ZERO ERA Mack and his artist friends 5th September until 31st October 2014 left: Heinz Mack, Dynamische Struktur schwarz-weiß, resin on canvas, 1961, 130 x 110 cm right: Otto Piene, Es brennt, Öl, oil, fire and smoke on linen, 1966, 79,6 x 99,8 cm Beck & Eggeling presents at the start of the autumn season the exhibition „ZERO ERA. Mack and his artist friends“ - works from the Zero movement from 1957 until 1966. The opening will take place on Friday, 5th September 2014 at 6 pm at Bilker Strasse 5 and 4-6 in Duesseldorf, on the occasion of the gallery weekend 'DC Open 2014'. Heinz Mack will be present. After ten years of intense and successful cooperation between the gallery and Heinz Mack, culminating in the monumental installation project „The Sky Over Nine Columns“ in Venice, the artist now opens up his private archives exclusively for Beck & Eggeling. This presents the opportunity to delve into the ZERO period, with a focus on the oeuvre of Heinz Mack and his relationship with his artist friends of this movement. Important artworks as well as documents, photographs, designs for invitations and letters bear testimony to the radical and vanguard ideas of this period. To the circle of Heinz Mack's artist friends belong founding members Otto Piene and Günther Uecker, as well as the artists Bernard Aubertin, Hermann Bartels, Enrico Castellani, Piero BECK & EGGELING BILKER STRASSE 5 | D 40213 DÜSSELDORF | T +49 211 49 15 890 | [email protected] Dorazio, Lucio Fontana, Hermann Goepfert, Gotthard Graubner, Oskar Holweck, Yves Klein, Yayoi Kusama, Walter Leblanc, Piero Manzoni, Almir da Silva Mavignier, Christian Megert, George Rickey, Jan Schoonhoven, Jesús Rafael Soto, Jean Tinguely and Jef Verheyen, who will also be represented in this exhibition. -

Sanjski Grad Vsakega Umetnika« – Japonski Avantgardni Center V 60

DOI: 10.4312/as.2016.4.2.183-200 183 »Sanjski grad vsakega umetnika« – Japonski avantgardni center v 60. letih 20. stoletja Klara HRVATIN* Izvleček Članek predstavlja uvod v predstavitev umetniškega gibanja Sōgetsu (1958–1971), nje- govega mesta v zgodovini japonske avantgardne scene, pomembnosti umetniškega centra Sōgetsu (Sōgetsu Art Center ali SAC), kjer se je gibanje odvijalo, in njegovega mecena Sōfuja Teshigahare. Ob pregledu prvih obstoječih dokumentov o SAC-u, prvega, ki je služil kot uvodni vodič Centra (objavljen 1. septembra 1958), in drugega, ki je bil eksklu- zivno izdan ob njegovem odprtju (13. septembra 1958), bomo lahko natančneje razkrili SAC-ovo podobo in kapacitete ter opredelili cilje, ki si jih je postavil pred začetkom delo- vanja. Kaj je Center nudil, da je bil razglašen za »sanjski grad vsakega umetnika«? Ključne besede: japonska avantgardna umetnost, umetniško gibanje Sōgetsu, umetniški center Sōgetsu, Sōfu Teshigahara, šola ikebane Sōgetsu Abstract This article is an introduction to the Sōgetsu art movement (1958–1971): its importance in the history of the Japanese avant-garde, and the significance of the Sōgetsu Art Center (SAC) itself, including its patron Sōfu Teshigahara. By examining the first two print- ed materials on SAC, the first of which served as an introductory guide to the Center (published on September 1st, 1958), and the second printed exclusively for the Center’s opening (September 13th, 1958), we will consider the Center’s appearance and facilities and point out its functions, which Teshigahara assigned from its begining. What were the Center’s particular features by which it got called “the dream castle of every artist”? Keywords: Japanese avant-garde, Sōgetsu art movement, Sōgetsu Art Center (SAC), Sōfu Teshigahara, Sōgetsu ikebana school * Klara HRVATIN, dr., Oddelek za azijske študije, Filozofska fakulteta, Univerza v Ljubljani. -

Exhibiting Performance Art's History

EXHIBITING PERFORMANCE ART’S HISTORY Harry Weil 100 Years (version #2, ps1, nov 2009), a group show at MoMA PS1, Long Island City, New York, November 1, 2009 –May 3, 2010 and Off the Wall: Part 1—Thirty Performative Actions, a group show at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City, July 1–September 19, 2010. he past decade has born witness 100 Years, curated by MoMA PS1 cura- to the proliferation of perfor- tor Klaus Biesenbach and art historian mance art in the broadest venues RoseLee Goldberg, structured a strictly Tyet seen, with notable retrospectives of linear history of performance art. A Marina Abramović, Gina Pane, Allan five-inch thick straight blue line ran the Kaprow, and Tino Sehgal held in Europe length of the exhibition, intermittently and North America. Performance has pierced by dates written in large block garnered a space within the museum’s letters. The blue path mimics the simple hallowed halls, as these institutions have red and black lines of Alfred Barr’s chart hurriedly begun collecting performance’s on the development of modern art. Barr, artifacts and documentation. As such, former director of MoMA, created a museums play an integral role in chroni- simple scientific chart for the exhibition cling performance art’s little-detailed Cubism and Abstract Art (1935) that history. 100 Years (version #2, ps1, nov streamlines the genealogy of modern 2009) at MoMA PS1 and Off the Wall: art with no explanatory text, reduc- Part 1—Thirty Performative Actions at ing it to a chronological succession of the Whitney Museum of American avant-garde movements. -

Otto Piene: Lichtballett

Otto Piene: Lichtballett a complete rewiring of the piece, removal of surface damage and dents, and team of artists for documenta 6, was later exhibited on the National Mall in replacement of the light fixtures and bulbs to exact specifications. Washington, DC. For the closing ceremony of the 1972 Munich Olympics, The MIT List Visual Arts Center is pleased to present an exhibition of the Piene created Olympic Rainbow, a “sky art” piece comprised of five helium- light-based sculptural work of Otto Piene (b. 1928, Bad Laasphe, Germany). The exhibition also showcases several other significant early works filled tubes that flew over the stadium. Piene received the Sculpture Prize Piene is a pioneering figure in multimedia and technology-based art. alongside new sculptures. The two interior lamps of Light Ballet on Wheels of the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1996. He lives and works in Known for his smoke and fire paintings and environmental “sky art,” Piene (1965) continuously project light through a revolving disk. The sculpture Groton, Massachusetts, and Düsseldorf, Germany. formed the influential Düsseldorf-based Group Zero with Heinz Mack in Electric Anaconda (1965) is composed of seven black globes of decreasing the late 1950s. Zero included artists such as Piero Manzoni, Yves Klein, Jean diameter stacked in a column, the light climbing up until completely lit. Tinguely, and Lucio Fontana. Piene was the first fellow of the MIT Center Piene’s new works produced specifically for the exhibition, Lichtballett for Advanced Visual Studies (CAVS) in 1968, succeeding its founder György (2011), a site-specific wall sculpture, and One Cubic Meter of Light Black Kepes as director until retiring in 1994. -

Kusama 2 1 Zero Gutai Kusama

ZERO GUTAI KUSAMA 2 1 ZERO GUTAI KUSAMA VIEWING Bonhams 101 New Bond Street London, W1S 1SR Sunday 11 October 11.00 - 17.00 Monday 12 October 9.00 - 18.00 Tuesday 13 October 9.00 - 18.00 Wednesday 14 October 9.00 - 18.00 Thursday 15 October 9.00 - 18.00 Friday 16 October 9.00 - 18.00 Monday 19 October 9.00 - 17.00 Tuesday 20 October 9.00 - 17.00 EXHIBITION CATALOGUE £25.00 ENQUIRIES Ralph Taylor +44 (0) 20 7447 7403 [email protected] Giacomo Balsamo +44 (0) 20 7468 5837 [email protected] PRESS ENQUIRIES +44 (0) 20 7468 5871 [email protected] 2 1 INTRODUCTION The history of art in the 20th Century is punctuated by moments of pure inspiration, moments where the traditions of artistic practice shifted on their foundations for ever. The 1960s were rife with such moments and as such it is with pleasure that we are able to showcase the collision of three such bodies of energy in one setting for the first time since their inception anywhere in the world with ‘ZERO Gutai Kusama’. The ZERO and Gutai Groups have undergone a radical reappraisal over the past six years largely as a result of recent exhibitions at the New York Guggenheim Museum, Berlin Martin Gropius Bau and Amsterdam Stedelijk Museum amongst others. This escalation of interest is entirely understandable coming at a time where experts and collectors alike look to the influences behind the rapacious creativity we are seeing in the Contemporary Art World right now and in light of a consistently strong appetite for seminal works. -

Ari Benjamin Meyers

ARI BENJAMIN MEYERS Born 1972 (New York, USA) Lives and works in Berlin, Germany EDUCATION 1996–1998 Fullbright Grant: Hochschule für Musik Hanns Eisler, Berlin, Germany, Certificate in Conducting 1994–1996 The Peabody Institue, Baltimore, Maryland, USA, MM Conducting 1990–1994 Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, USA, BA Composition (Cum Laude) 1990–1997 The Juilliard School Pre-College Division, New York, New York, USA, Composition and Piano SOLO EXHIBITIONS AND PRESENTATIONS 2019 In Concert, OGR – Officine Grandi Riparazioni, Turin, Italy 2018 Kunsthalle for Music, Witte de With, Rotterdam, Netherlands 2017 An exposition, not an exhibition, Spring Workshop, Hong Kong, China Solo for Ayumi, Esther Schipper, Berlin, Germany 2016 The Name Of This Band is The Art, RaebervonStenglin, Zurich, Switzerland 2015 Atlas of Melodies, abc Berlin, Berlin, Germany 2013 Black Thoughts, Esther Schipper, Berlin, Germany Songbook, Esther Schipper, Berlin, Germany SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2016 Musikwerke Bildene Künstler, Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin, Germany Oscillations, Trafo Center for Contemporary Art, Szczecin, Poland 2015 music, Fahrbereitschaft – Haubrok Collection, Berlin, Germany Artists’ Weekend, Ngorongoro, Berlin, Germany The Verismo Project, Kunst im Kino, Kino International, Berlin, Germany 2014 Supergroup, Tanzhaus NRW, Düsseldorf, Germany I Take Part and the Part Takes Me, Gallery Tanja Wagner, Berlin, Germany The New Empirical, Hatje Cantz & Du Moulin im Bikini, Berlin, Germany 2012 I Wish This Was a Song. Music in Contemporary Art,