OTHERWISE Rethinking Museums and Heritage CARMAH Paper #1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Berlin's New Cultural Heart

I Research Text Berlin’s new cultural heart Cultural stronghold and historical centre Berlin, September 2017 – Today, Berlin belongs to one of Europe’s leading centres of culture – and its heart beats strongest directly in the old historical city. For centuries, Berlin’s city centre has been home to a unique concentration of outstanding cultural institutions constructed on the ground where the medieval city of Berlin was founded. The modern Mitte district does not just boast the UNESCO World Heritage Site of the Museum Island, but also two opera houses and six major theatres, as well as museums, innumerable galleries and arts venues. Now, this cultural ensemble is gaining a new dimension with many new major cultural projects located here, just a few minutes’ walk apart. You can find an overview of the main on-going and planned landmark projects below. Pierre Boulez Saal Opened in March 2017, the new Pierre Boulez Saal is a major international concert hall. Initiated by Daniel Barenboim, General Music Director of the Staatsoper Unter den Linden, the hall was developed by American architect Frank Gehry and with globally acclaimed acoustician Yasuhisa Toyota creating the impeccable acoustics. Lined with light Canadian cedarwood, the Pierre-Boulez-Saal offers a flexible design allowing the auditorium’s seating as well as the stage to be arranged in various constellations for a wide spectrum of events. The concert hall is also the public face of the Barenboim-Said Akademie, not only serving as its home venue but also a space where young musicians from conflict zones in the Middle East can practice under the guidance of their mentors. -

Lange Nacht Der Museen JUNGE WILDE & ALTE MEISTER

31 AUG 13 | 18—2 UHR Lange Nacht der Museen JUNGE WILDE & ALTE MEISTER Museumsinformation Berlin (030) 24 74 98 88 www.lange-nacht-der- M u s e e n . d e präsentiert von OLD MASTERS & YOUNG REBELS Age has occupied man since the beginning of time Cranach’s »Fountain of Youth«. Many other loca- – even if now, with Europe facing an ageing popula- tions display different expression of youth culture tion and youth unemployment, it is more relevant or young artist’s protests: Mail Art in the Akademie than ever. As far back as antiquity we find unsparing der Künste, street art in the Kreuzberg Museum, depictions of old age alongside ideal figures of breakdance in the Deutsches Historisches Museum young athletes. Painters and sculptors in every and graffiti at Lustgarten. epoch have tackled this theme, demonstrating their The new additions to the Long Night programme – virtuosity in the characterisation of the stages of the Skateboard Museum, the Generation 13 muse- life. In history, each new generation has attempted um and the Ramones Museum, dedicated to the to reform society; on a smaller scale, the conflict New York punk band – especially convey the atti- between young and old has always shaped the fami- tude of a generation. There has also been a genera- ly unit – no differently amongst the ruling classes tion change in our team: Wolf Kühnelt, who came up than the common people. with the idea of the Long Night of Museums and The participating museums have creatively picked who kept it vibrant over many years, has passed on up the Long Night theme – in exhibitions, guided the management of the project.We all want to thank tours, films, talks and music. -

Staatliche Museen Zu Berlin September 24–29, 2017 September, 2017

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin September 24–29, 2017 September, 2017 Dear PREP Participants Welcome back to PREP and Willkommen in Berlin! It is wonderful to have you all here. We hope the coming week will be as interesting and insightful as the week we spent in New York in February. Over the coming days, we aim to introduce you to the key re- sources Berlin has to offer to researchers studying art losses in the Nazi-Era and also to other colleagues here in Berlin who are involved in provenance research in a variety of ways. We would also like to make you familiar with some of the institutions that are part of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin and give you an idea of the work they are doing with regard to provenance research. Most of all, however, we would like to provide the setting in which you can continue the conversations you began in New York and carry on building the network that is PREP. We have asked you to contribute to quite a few of the events – thank you all for your many ideas and suggestions! We have tried to build PREP around the participants and your expertise and input are crucial to the success of the program. This applies not only to the coming week, but also to the future develop- ment of the PREP-Network. There are two ways in which we hope you will contribute to the long term success of PREP. One of these is that we hope you will all keep in touch after you leave Berlin and continue supporting each other in the impor- tant work you do. -

60 Incoherent Renovation in Berlin: Is There a Way

New Design Ideas Vol.3, No.1, 2019, pp.60-78 INCOHERENT RENOVATION IN BERLIN: IS THERE A WAY FORWARD? Malcolm Millais Independent researcher, Porto, Portugal Abstract. This paper briefly describes the fates of four of Berlin‟s most iconic cultural buildings. These are the Berlin Palace, the Neues Museum, the Berlin Dom (Cathedral) and the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church. Using a variety of historical styles, all these buildings were built, or finished, in the nineteenth century, and all suffered serious damage due to aerial bombing in the Second World War. As all were repairable, the obvious choice might seem to reinstate them to their original condition: but this did not happen to any of them. This paper examines the incoherence of the various renovations, and briefly addresses the problem of formulating a coherent approach to renovation, particularly with reference to the 1964 Venice Charter. Keywords: Berlin, renovation, Venice Charter, iconic buildings, war damage, monstrous carbuncle, wartime bombing, cultural destruction. Corresponding Author: Malcolm Millais, Porto, Portugal, e-mail: [email protected] Received: 4 December 2018; Accepted: 24 January 2019; Published: 28 June 2019. 1. Introduction What can be said about all four of the buildings examined here is that: All, except in some aspects the Neues Museum, were extremely solidly built, so, given routine maintenance, could have be expected to have lasted for probably hundreds of years. All were severely damaged by aerial bombing during the Second World War. All were repairable. All suffered further destruction due to various political ideologies such as Communism, Modernism and Nationalism. All have been reinstated in a variety of ways, none of which are universally accepted. -

I Basic Information

I Basic Information Berlin’s new cultural heart Cultural stronghold and historical centre Berlin, September 2017 – Today, Berlin belongs to one of Europe’s leading centres of culture – and its heart beats strongest directly in the old historical city. For centuries, Berlin’s city centre has been home to a unique concentration of outstanding cultural institutions constructed on the ground where the medieval city of Berlin was founded. The modern Mitte district does not just boast the UNESCO World Heritage Site of the Museum Island, but also two opera houses and six major theatres, as well as museums, innumerable galleries and arts venues. Now, this cultural ensemble is gaining a new dimension with many new major cultural projects located here, just a few minutes’ walk apart. You can find an overview of the main on-going and planned landmark projects below. Pierre Boulez Saal Opened in March 2017, the new Pierre Boulez Saal is a major international concert hall. Initiated by Daniel Barenboim, General Music Director of the Staatsoper Unter den Linden, the hall was developed by American architect Frank Gehry and with globally acclaimed acoustician Yasuhisa Toyota creating the impeccable acoustics. Lined with light Canadian cedarwood, the Pierre-Boulez-Saal offers a flexible design allowing the auditorium’s seating as well as the stage to be arranged in various constellations for a wide spectrum of events. The concert hall is also the public face of the Barenboim-Said Akademie, not only serving as its home venue but also a space where young musicians from conflict zones in the Middle East can practice under the guidance of their mentors. -

The Berlin Palace Becomes the Humboldt Forum

THE BERLIN PALACE BECOMES THE HUMBOLDT FORUM The Reconstruction and Transformation of Berlin’s City Centre Manfred Rettig THE BERLIN PALACE BECOMES THE HUMBOLDT FORUM The Reconstruction and Transformation of Berlin’s City Centre Manfred Rettig Chief Executive Officer and spokesperson for the Berlin Palace—Humboldt Forum Foundation The Berlin Palace—Humboldt Forum (Berliner Schloss— Now, with the Berlin Palace—Humboldt Forum, the centre of Humboldtforum) will make this historic locality in the centre of Berlin’s inner city will be redesigned and given a new archi- the German capital a free centre of social and cultural life, tectural framework. This is not merely a makeshift solution – open to all, in a democratic spirit. Here, with the rebuilding it is a particularly ambitious challenge to create this new of the Berlin Palace, visitors can experience German history cultural focus in the skin of an old building. There are many in all its event-filled variety. The Humboldt Forum makes the lasting and valid justifications for this approach, and the Palace part of a new ensemble looking to the future. matter has been discussed for almost twenty years. Not only The building was commissioned and is owned by the will the project restore the reference point, both proportion- Berlin Palace—Humboldt Forum Foundation, founded in ally and in terms of content, for all the surrounding historic November 2009 by the German government. A legally respon- buildings – the Protestant state church with the cathedral sible foundation in civil law, it is devoted directly and exclu- (Berliner Dom), and Prussian civic culture with the Museum sively to public interests in promoting art and culture, educa- Island (Museumsinsel) – but, more importantly, the historic tion, international orientation, tolerance in all fields of culture centre of Berlin will be recognised as such and taken more and understanding between nations, and to the preservation seriously, after its almost complete destruction as a conse- and curating of historic monuments. -

Download File

Inclusive National Belonging Intercultural Performances in the “World-Open” Germany Bruce Snedegar Burnside Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2020 © 2020 Bruce Snedegar Burnside All Rights Reserved Abstract Inclusive National Belonging Intercultural Performances in the “World-Open” Germany Bruce Snedegar Burnside This dissertation explores what it means to belong in Berlin and Germany following a significant change in the citizenship laws in 2000, which legally reoriented the law away from a “German” legal identity rooted in blood-descent belonging to a more territorially-based conception. The primary goal is to understand attempts at performing inclusive belonging by the state and other actors, with mostly those of “foreign heritage” at the center, and these attempts’ pitfalls, opportunities, challenges, and strange encounters. It presents qualitative case studies to draw attention to interculturality and its related concepts as they manifest in a variety of contexts. This study presents a performance analysis of a ceremony at a major national museum project and utilizes a discursive analysis of the national and international media surrounding a unique controversy about soccer and Islam. The study moves to a peripheral neighborhood in Berlin and a marginal subject, a migration background Gymnasium student, who featured prominently in an expose about failing schools, using interviews and a text analysis to present competing narratives. Finally it examines the intimate, local view of a self-described “intercultural” after- school center aimed at migration-background girls, drawing extensively on ethnographic interviews and media generated by the girls.These qualitative encounters help illuminate how an abstract and often vague set of concepts within the intercultural paradigm becomes tactile when encountering those for whom it was intended. -

17/0183 22.02.2012 17

Drucksache 17/0183 22.02.2012 17. Wahlperiode Vorlage – zur Beschlussfassung – Entwurf des Bebauungsplans I-219 (Humboldt-Forum) für das Gelände zwischen Schloßbrücke, Schloßplatz, Liebknechtbrücke, Spree, Rathausbrücke,Schloßplatz, Schleusenbrücke und Spreekanal sowie die Rathausbrücke, einen Abschnittder Spree und eine Teilfläche des Schloßplatzes im Bezirk Mitte, Ortsteil Mitte Der Senat von Berlin - Stadt Um II B 13 – Tel.: 9025-2109 An das Abgeordnetenhaus von Berlin über Senatskanzlei – G Sen – Vorblatt Vorlage – zur Beschlussfassung – über den Entwurf des Bebauungsplans I-219 (Humboldt-Forum) für das Gelände zwischen Schloßbrücke, Schloßplatz, Liebknechtbrücke, Spree, Rathausbrü- cke, Schloßplatz, Schleusenbrücke und Spreekanal sowie die Rathausbrücke, einen Abschnitt der Spree und eine Teilfläche des Schloßplatzes im Bezirk Mitte, Ortsteil Mitte A. Problem Die gegenwärtige städtebauliche Situation im Plangebiet wird der besonderen Bedeu- tung des Ortes nicht gerecht. Auf der Grundlage der entsprechenden Beschlüsse des Deutschen Bundestages und des Landes Berlin sollen die planungsrechtlichen Voraus- setzungen für den Bau des künftigen Humboldt-Forums in der Kubatur des früheren Schlosses geschaffen und der Standort für ein Freiheits- und Einheitsdenkmal - unter Be- rücksichtigung des denkmalgeschützten Sockels des ehemaligen Nationaldenkmals - gesichert werden. Das Plangebiet übernimmt im Rahmen seiner Funktion als Standort für eines der bedeu- tendsten kulturellen Bauvorhaben Deutschlands, mit dem Nutzungszweck des sonstigen Sondergebietes für Kultur, Bildung und Forschung, eine besondere öffentliche Aufgabe, die allein über die Regelungen der Zulässigkeit von Vorhaben nach § 34 BauGB nicht zu sichern ist. Auch ist die gegenwärtig nach § 34 BauGB zu beurteilende Zulässigkeit von Vorhaben unzureichend, um die städtebauliche Zielsetzung der Reurbanisierung des Plangebiets unter Berücksichtigung des Wettbewerbsergebnisses umzusetzen. Dies ist nur mit dem Instrument des Bebauungsplans möglich. -

The Turfan Textile Collection and the Humboldt Forum

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2014 A Fragmented Treasure on Display: The urT fan Textile Collection and the Humboldt Forum Mariachiara Gasparini University of Heidelberg, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art Practice Commons, Asian Art and Architecture Commons, Chinese Studies Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, and the Museum Studies Commons Gasparini, Mariachiara, "A Fragmented Treasure on Display: The urT fan Textile Collection and the Humboldt Forum" (2014). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 946. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/946 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. A FRAGMENTED TREASURE ON DISPLAY. THE TURFAN TEXTILE COLLECTION AND THE HUMBOLDT FORUM. Mariachiara Gasparini In 2011, the first time I saw a few fragments of the Turfan textile collection, held in the Museum für Asiatische Kunst (Museum of Asian Art) in Berlin, I had no idea that they represented only a small part of a range of about three hundred fifty compounds that, different in style and technique and datable to between the eighth and the fourteenth centuries, comprised the collection. The fragments were gathered, together with wall paintings, architectural wooden structures, sculptures, and other tools of daily use, during the four Prussian-Turfan expeditions conducted by Albert Grünwedel (1856-1935) and Albert von Le Coq (1860-1930) at the beginning of the last century, between 1902 and 1914, in the Xinjiang Province of China. -

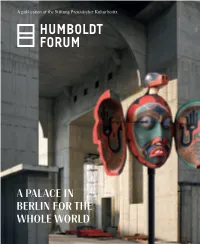

A Palace in Berlin for the Whole World

A publication of the Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz A PALACE IN BERLIN FOR THE WHOLE WORLD MF 1 Humboldt Forum Humboldt Forum HP The presentation in Dahlem still follows the nar- What connects Alaska and Berlin? TIME TO TALK rative of an ethnological museum – very static and offering little scope for change. In the Humboldt How to build a Buddhist cave in a museum? Forum we’ll be able to be much more flexible and to Where were icons invented? ABOUT CONTENT tell the stories from multiple perspectives, allowing the voices of the indigenous cultures from which the A Q&A session with Hermann Parzinger, objects came to be heard. And we will try to focus To find out all this and more, come more than in Dahlem on current issues like climate and visit the new cultural heart of Berlin change and migration. In fact, we’ll be dealing with President of the all the major issues that concern us today. 5. Last spring, the Federal Government Commis- Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz sioner for Culture appointed a trio as founding directors of the Humboldt Forum: yourself, the art historian Horst Bredekamp, and Neil MacGregor, 1. We’re standing in the shell of the Stadtschloss, former director of London’s British Museum, as the Berlin Palace. Where exactly are we? team leader. The press enthused wildly about the HERMANN PARZINGER In the foyer, near the main entrance choice of MacGregor and his acceptance of the directly under the cupola. The visitors’ routes through post. What makes him the right person? the building will all lead off from this vast hall. -

The Duality of Multiculturalism in 1500'S and Contemporary Germany

Artl@s Bulletin Volume 2 Article 7 Issue 1 Arts, Spaces, Identities 2013 The Duality of Multiculturalism in 1500’s and Contemporary Germany: Between Political and Curated Cultural Capital Courtney Dorroll University of Arizona, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/artlas Recommended Citation Dorroll, Courtney. "The Duality of Multiculturalism in 1500’s and Contemporary Germany: Between Political and Curated Cultural Capital." Artl@s Bulletin 2, no. 1 (2013): Article 7. This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. This is an Open Access journal. This means that it uses a funding model that does not charge readers or their institutions for access. Readers may freely read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of articles. This journal is covered under the CC BY-NC-ND license. Arts, Spaces, Identities The Duality of Multiculturalism in 1500’s and Contemporary Germany: Between Political and Curated Cultural Capital Courtney Dorroll* University of Arizona Abstract My research analyzes the hegemonic power of museums through the use of Jean Baudrillard’s concept of simulacra and Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of cultural capital. I analyze museum objects and museum signage in Berlin’s temporary exhibit in the Humboldt Box and the permanent Ottoman collection on display in the Pergamon’s Museum of Islamic Art juxtaposed with anti-Turkish rhetoric as seen as early as the 16th century in Edward Schoen’s woodblock prints as well as political speeches that have taken place within the last five years in Germany. -

Darkmatter Journal » the Making of Berlin's Humboldt-Forum

darkmatter Journal » The Making of Berlin’s Humboldt-Forum: Negotiating History and the Cult... http://www.darkmatter101.org/site/2013/11/18/the-making-of-berlin’s-humboldt-forum-negotiati... - darkmatter Journal - http://www.darkmatter101.org/site - The Making of Berlin’s Humboldt-Forum: Negotiating History and the Cultural Politics of Place Friedrich von Bose | Journal: Afterlives [11] | Commons | Issues | Nov 2013 After more than 15 years of intense public debate about the future of the Spree Island and the Palace Square (Schlossplatz) in Berlin, the German Bundestag decided in July 2002 for the much-contested reconstruction of the historical Prussian city palace. The palace, having served as the principal residence of Brandenburg margraves and electors and later of Prussian kings and the German Emperor, was partly demolished during WWII and subsequently, in 1950, blasted by the GDR government of Walter Ulbricht. In 1973, the Palace of the Republic (Palast der Republik) was built on the eastern side of the Palace Square, housing the GDR People’s Parliament and serving as popular venue for cultural events after its inception in 1976. Importantly, the 2002 decision implied that the Palace of the Republic, one of the most important architectural monuments of the former GDR’s capital in the now unified Berlin, would be torn down. It was decided that it should give place to a new building in the cubature of the former city palace, including the reconstruction of its historical baroque facades on three sides of the building.[1] Fig 1: The “Humboldt-Box”, bordering on the palace’s construction site, advertizes the future Humboldt-Forum © Bose.