Who Is a Muslim?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S# BRANCH CODE BRANCH NAME CITY ADDRESS 1 24 Abbottabad

BRANCH S# BRANCH NAME CITY ADDRESS CODE 1 24 Abbottabad Abbottabad Mansera Road Abbottabad 2 312 Sarwar Mall Abbottabad Sarwar Mall, Mansehra Road Abbottabad 3 345 Jinnahabad Abbottabad PMA Link Road, Jinnahabad Abbottabad 4 131 Kamra Attock Cantonment Board Mini Plaza G. T. Road Kamra. 5 197 Attock City Branch Attock Ahmad Plaza Opposite Railway Park Pleader Lane Attock City 6 25 Bahawalpur Bahawalpur 1 - Noor Mahal Road Bahawalpur 7 261 Bahawalpur Cantt Bahawalpur Al-Mohafiz Shopping Complex, Pelican Road, Opposite CMH, Bahawalpur Cantt 8 251 Bhakkar Bhakkar Al-Qaim Plaza, Chisti Chowk, Jhang Road, Bhakkar 9 161 D.G Khan Dera Ghazi Khan Jampur Road Dera Ghazi Khan 10 69 D.I.Khan Dera Ismail Khan Kaif Gulbahar Building A. Q. Khan. Chowk Circular Road D. I. Khan 11 9 Faisalabad Main Faisalabad Mezan Executive Tower 4 Liaqat Road Faisalabad 12 50 Peoples Colony Faisalabad Peoples Colony Faisalabad 13 142 Satyana Road Faisalabad 585-I Block B People's Colony #1 Satayana Road Faisalabad 14 244 Susan Road Faisalabad Plot # 291, East Susan Road, Faisalabad 15 241 Ghari Habibullah Ghari Habibullah Kashmir Road, Ghari Habibullah, Tehsil Balakot, District Mansehra 16 12 G.T. Road Gujranwala Opposite General Bus Stand G.T. Road Gujranwala 17 172 Gujranwala Cantt Gujranwala Kent Plaza Quide-e-Azam Avenue Gujranwala Cantt. 18 123 Kharian Gujrat Raza Building Main G.T. Road Kharian 19 125 Haripur Haripur G. T. Road Shahrah-e-Hazara Haripur 20 344 Hassan abdal Hassan Abdal Near Lari Adda, Hassanabdal, District Attock 21 216 Hattar Hattar -

Population Distribution in Sindh According to Census 2017 (Population of Karachi: Reality Vs Expectation)

Volume 3, Issue 2, February – 2018 International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology ISSN No:-2456 –2165 Population Distribution in Sindh According to Census 2017 (Population of Karachi: Reality vs Expectation) Dr. Faiza Mazhar TTS Assistant Professor Geography Department. Government College University Faisalabad, Pakistan Abstract—Sindh is our second largest populated province. Historical Populations Growth of Sindh It has a great role in culture and economy of Pakistan. Karachi the largest city of Pakistan in terms of population Census Year Total Population Urban Population also has a unique impact in development of Pakistan. Now 1951 6,047,748 29.23% according to the current census of 2017 Sindh is again 1961 8,367,065 37.85% standing on second position. Karachi is still on top of the list in Pakistan’s ten most populated cities. Population of 1972 14,155,909 40.44% Karachi has not grown on an expected rate. But it was due 1981 19,028,666 43.31% to many reasons like bad law and order situation, miss management of the Karachi and use of contraceptive 1998 29,991,161 48.75% measures. It would be wrong if it is said that the whole 2017 47,886,051 52.02% census were not conducted in a transparent manner. Source: [2] WWW.EN.WIKIPEDIA.ORG. Keywords—Component; Formatting; Style; Styling; Insert Table 1: Temporal Population Growth of Sindh (Key Words) I. INTRODUCTION According to the latest census of 2017 the total number of population in Sindh is 48.9 million. It is the second most populated province of Pakistan. -

Drivers of Climate Change Vulnerability at Different Scales in Karachi

Drivers of climate change vulnerability at different scales in Karachi Arif Hasan, Arif Pervaiz and Mansoor Raza Working Paper Urban; Climate change Keywords: January 2017 Karachi, Urban, Climate, Adaptation, Vulnerability About the authors Acknowledgements Arif Hasan is an architect/planner in private practice in Karachi, A number of people have contributed to this report. Arif Pervaiz dealing with urban planning and development issues in general played a major role in drafting it and carried out much of the and in Asia and Pakistan in particular. He has been involved research work. Mansoor Raza was responsible for putting with the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP) since 1981. He is also a together the profiles of the four settlements and for carrying founding member of the Urban Resource Centre (URC) in out the interviews and discussions with the local communities. Karachi and has been its chair since its inception in 1989. He was assisted by two young architects, Yohib Ahmed and He has written widely on housing and urban issues in Asia, Nimra Niazi, who mapped and photographed the settlements. including several books published by Oxford University Press Sohail Javaid organised and tabulated the community surveys, and several papers published in Environment and Urbanization. which were carried out by Nur-ulAmin, Nawab Ali, Tarranum He has been a consultant and advisor to many local and foreign Naz and Fahimida Naz. Masood Alam, Director of KMC, Prof. community-based organisations, national and international Noman Ahmed at NED University and Roland D’Sauza of the NGOs, and bilateral and multilateral donor agencies; NGO Shehri willingly shared their views and insights about e-mail: [email protected]. -

Health Facilities in Thatta- Sindh Province

PAKISTAN: Health facilities in Thatta- Sindh province Matiari Balochistan Type of health facilities "D District headquarter (DHQ) Janghari Tando "T "B Tehsil headquarter (THQ) Allah "H Civil hospital (CH) Hyderabad Yar "R Rural health center (RHC) "B Basic health unit (BHU) Jamshoro "D Civil dispensary (CD) Tando Las Bela Hafiz Road Shah "B Primary Boohar Muhammad Ramzan Secondary "B Khan Haijab Tertiary Malkhani "D "D Karachi Jhirck "R International Boundary MURTAZABAD Tando City "B Jhimpir "B Muhammad Province Boundary Thatta Pir Bux "D Brohi Khan District Boundary Khair Bux Muhammad Teshil Boundary Hylia Leghari"B Pinyal Jokhio Jungshahi "D "B "R Chatto Water Bodies Goth Mungar "B Jokhio Chand Khan Palijo "B "B River "B Noor Arbab Abdul Dhabeeji Muhammad Town Hai Palejo Thatta Gharo Thaheem "D Thatta D "R B B "B "H " "D Map Doc Name: PAK843_Thatta_hfs_L_A3_ "" Gujjo Thatta Shah Ashabi Achar v1_20190307 Town "B Jakhhro Creation Date: 07 March 2019 Badin Projection/Datum: GCS/WGS84 Nominal Scale at A3 paper size: 1:690,000 Haji Ghulammullah Pir Jo "B Muhammad "B Goth Sodho RAIS ABDUL 0 10 20 30 "B GHANI BAGHIAR Var "B "T Mirpur "R kms ± Bathoro Sindh Map data source(s): Mirpur GAUL, PCO, Logistic Cluster, OCHA. Buhara Sakro "B Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any Thatta opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

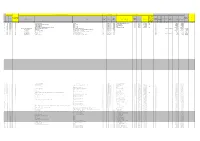

Code Name CNIC No/ Passport No Name Address Nature of Deposit

DETAILS OF THE BRANCH DETAILS OF THE DEPOSITOR/BENEFICIARY OF THE INSTRUMENT DETAILS OF THE ACCOUNT DETAILS OF THE INSTRUMENT Transaction Federal/Provi NAME OF THE PROVINCE IN ncial Last date of deposit or S. No WHICH ACCOUNT OPENED / withdrawal (DD- Remarks Account Type ISNTRUMENT PAYABLE Instrument Type (FED/PRO) In Currency MON-YYYY) Nature of Deposit ( e.g Current, Rate Type FCS Contract Rate of PKR Rate applied date code Name CNIC No/ Passport No Name Address Account Number Name of the Applicant/Purchaser (DD,PO,FDD,TD Instrument No. Date of Issue (USD,EUR,GBP,AE Amount Outstanding Eqv.PKR surrendered (LCY,UFZ,FZ) Saving, Fixed or any Case of (MTM,FCSR) No (if any) conversion (DD-MON-YYYY) R,CO) D,JPY,CHF) other) Instrument favoring the Government 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 1 791 Lahore PB CMA (POF) Wah Cantt Wah Cantt LCY 1052695-00-0 Current Fresenius Medical Care pakistan Pvt Ltd PO 394760 9/14/2009 FED PKR 7,200.00 7,200.00 2 791 Lahore PB Pakistan International AirlineLlahore Airport Lahore-Pakistan LCY 1038462-00-0 Current KSB Pumps Co Ltd PO 395643 11/11/2009 FED PKR 1,000.00 1,000.00 3 791 Lahore PB Yaaseen Shipping Lines Karachi LCY 1041029-00-0 Current Escorts Pakistan Ltd PO 392581 5/14/2009 PKR 1,800.00 1,800.00 4 791 Lahore PB Ahmed Waheed Malik Lahore-Pakistan LCY 0190751-00-0 Current CRES PO 383470 4/13/2009 PKR 73.00 73.00 5 791 Lahore PB The Chief Purchase officer,Health Department,Govt of Punjab Lahore-Pakistan LCY 0056481-00-0 Current B Braun Pakistan Pvt Ltd PO 395718 11/18/2009 -

Sialkot District Reference Map September, 2014

74°0'0"E G SIALKOT DISTRICT REFBHEIMRBEER NCE MAP SEPTEMBER, 2014 Legend !> GF !> !> Health Facility Education Facility !>G !> ARZO TRUST BHU CHITTI HOSPITAL & SHEIKHAN !> MEDICAL STORE !> Sialkot City !> G Basic Health Unit !> High School !> !> !> G !> MURAD PUR BASHIR A CHAUDHARY AL-SHEIKH HOSPITAL JINNAH MEMORIAL !> MEMORIAL HOSPITAL "' CHRISTIAN HOSPITAL ÷Ó Children Hospital !> Higher Secondary IQBAL !> !> HOSPITAL !>G G DISPENSARY HOSPITAL CHILDREN !> a !> G BHAGWAL DHQ c D AL-KHIDMAT HOSPITAL OA !> SIALKOT R Dispensary AWAN BETHANIA !>CHILDREN !>a T GF !> Primary School GF cca ÷Ó!> !> A WOMEN M!>EDICAaL COMPLEX HOSPITAL HOSPITAL !> ÷Ó JW c ÷Ó !> '" A !B B D AL-SHIFA HOSPITAL !> '" E ÷Ó !> F a !> '" !B R E QURESHI HOScPITAL !> ALI HUSSAIN DHQ O N !> University A C BUKH!>ARI H M D E !>!>!> GENERAL E !> !> A A ZOHRA DISPENSARY AG!>HA ASAR HOSPITAL D R R W A !B GF L AL-KHAIR !> !> HEALTH O O A '" Rural Health Center N MEMORIAL !> HOSPITAL A N " !B R " ú !B a CENTER !> D úK Bridge 0 HOSPITAL HOSPITAL c Z !> 0 ' A S ú ' D F úú 0 AL-KHAIR aA 0 !> !>E R UR ROA 4 cR P D 4 F O W SAID ° GENERAL R E A L- ° GUJORNAT !> AD L !> NDA 2 !> GO 2 A!>!>C IQBAL BEGUM FREE DISPENSARY G '" '" Sub-Health Center 3 HOSPITAL D E !> INDIAN 3 a !> !>!> úú BHU Police Station AAMNA MEDICAL CENTER D MUGHAL HOSPIT!>AL PASRUR RD HAIDER !> !>!> c !> !>E !> !> GONDAL G F Z G !>R E PARK SIALKOT !> AF BHU O N !> AR A C GF W SIDDIQUE D E R A TB UGGOKI BHU OA L d ALI VETERINARY CLINIC D CHARITABLE BHU GF OCCUPIED !X Railway Station LODHREY !> ALI G !> G AWAN Z D MALAGAR -

Islamabad: Rawalpindi: Lahore: Karachi: Quetta

Contact list – Photo Studios - Pakistan The list below of photo studios in Pakistan has been compiled by the Australian High Commission, based on past experience, for client convenience only. The Australian High Commission does not endorse any of the photo studios appearing in the list, provides no guarantees as to their quality and does not accept any liability if you choose to engage one of these photo studios. Islamabad: Simco Photo Studio and Digital Colour Lab Photech Block 9-E, School Road, F-6 Markaz, Super Shop No. 7, Block 12, School Road, F-6 Markaz, Market, Islamabad – Pakistan, Super Market, Islamabad 051-2822600, 051-2826966 051-2275588, 051-2874583 Rawalpindi: Lahore: Jumbo Digital Lab & Photo Studio AB Digital Color Lab and Studio Chandni Chowk, Murree Road, Rawalpindi Kashif Centre, 80-Chowk Nisbat Road 051-4906923, 051-4906089, 051-4456088 Lahore – Pakistan, 042-37226496, 042-37226611 Karachi: Dossani’s Studio Disney’s Digital Photo Studio Hashoo Terrace, Khayaban-e-Roomi, Boat Basin, Shop No. 3, Decent Tower Shopping Centre, Clifton , Karachi, Gulistan-e-Johar, Block 15, Karachi Tell: +92-21-34013293, 0300-2932088 021-35835547, 021-35372609 Quetta: Sialkot Yadgar Digital Studio Qazi Studio Hussain Abad, Colonal Yunas Road, Hazara Qazi Mentions Town, Quetta. 0343-8020586 Railay Road Sialkot – Pakistan 052-4586083, 04595080 Peshawar: Azeem Studio & Digital Labs 467-Saddar Road Peshawar Cantt Tell: +91-5274812, +91-5271482 Camera Operator Guidelines: Camera: Prints: - High-quality digital or film camera - Print size 35mm -

"The Port Qasim Authority (Amendment) Bilt,2019"

NATIONAL ASSEMBLY SECRETARIAT PRESS RELEASE Islamabad the 2Sthseptember, 2020: 10th meeting of the Standing Committee on Maritime Affairs was held in Committee Room No.7, Parliament House, at 10:30 am under the Chairmanship of Mir Amer Ali Khan Magsi, MNA. The agenda of the meeting was circulated vide Notice No.F.8 (l)/2020-Com-l dated 17th September,2020. 2. The issue of containers stuck up at sea ports of Pakistan without any justification and also penalties imposed by foreign shipping companies and private terminal operators at ports for consignment arriving in Pakistan during lockdown period, was taken up by the Members of the Standing Committee Vice President of FPCCI and representative of Lahore Chamber of Commerce. It was told that although, an order was issued by the Director General of Shipping advising shipping lines not to impose container detention charges on import shipments but these are not only imposed and demurrage are also asked to be paid in billions. In other parts of the region, this has been waived off during the lockdown period of COVID-I9. The Committee vowed to take up this matter in the next scheduled meeting for the redressal ofgrievances. 3. The bills "The Port Qasim Authority (Amendment) Bilt,2019" and "The Gawadar Port Authority (Amendment) Bill,2019", were deferred for the next meeting in order to have more clarity from the Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Ministry of Law & Justice. 4. The meeting was attended by MNA's Mr. Muhammad Yaqoob Shaikh, Rana Muhammad Qasim Noon, Mr. Faheem Khan, Mr. Saif Ur Rehman, Mr. -

Preparatory Survey Report on the Project for Construction and Rehabilitation of National Highway N-5 in Karachi City in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan

The Islamic Republic of Pakistan Karachi Metropolitan Corporation PREPARATORY SURVEY REPORT ON THE PROJECT FOR CONSTRUCTION AND REHABILITATION OF NATIONAL HIGHWAY N-5 IN KARACHI CITY IN THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF PAKISTAN JANUARY 2017 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY INGÉROSEC CORPORATION EIGHT-JAPAN ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS INC. EI JR 17-0 PREFACE Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) decided to conduct the preparatory survey and entrust the survey to the consortium of INGÉROSEC Corporation and Eight-Japan Engineering Consultants Inc. The survey team held a series of discussions with the officials concerned of the Government of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, and conducted field investigations. As a result of further studies in Japan and the explanation of survey result in Pakistan, the present report was finalized. I hope that this report will contribute to the promotion of the project and to the enhancement of friendly relations between our two countries. Finally, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to the officials concerned of the Government of the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste for their close cooperation extended to the survey team. January, 2017 Akira Nakamura Director General, Infrastructure and Peacebuilding Department Japan International Cooperation Agency SUMMARY SUMMARY (1) Outline of the Country The Islamic Republic of Pakistan (hereinafter referred to as Pakistan) is a large country in the South Asia having land of 796 thousand km2 that is almost double of Japan and 177 million populations that is 6th in the world. In 2050, the population in Pakistan is expected to exceed Brazil and Indonesia and to be 335 million which is 4th in the world. -

Medieval India TNPSC GROUP – I & II

VETRII IAS STUDY CIRCLE Medieval India TNPSC GROUP – I & II An ISO 9001 : 2015 Institution | Providing Excellence Since 2011 Head Office Old No.52, New No.1, 9th Street, F Block, 1st Avenue Main Road, (Near Istha siddhi Vinayakar Temple), Anna Nagar East – 600102. Phone: 044-2626 5326 | 98844 72636 | 98844 21666 | 98844 32666 Branches SALEM KOVAI No.189/1, Meyanoor Road, Near ARRS Multiplex, No.347, D.S.Complex (3rd floor), (Near Salem New bus Stand), Nehru Street,Near Gandhipuram Opp. Venkateshwara Complex, Salem - 636004. Central Bus Stand, Ramnagar, Kovai - 9 Ph: 0427-2330307 | 95001 22022 Ph: 75021 65390 Educarreerr Location VIVEKANANDHA EDUCATIONA PATRICIAN COLLEGE OF ARTS SREE SARASWATHI INSTITUTIONS FOR WOMEN AND SCIENCE THYAGARAJA COLLEGE Elayampalayam, Tiruchengode - TK 3, Canal Bank Rd, Gandhi Nagar, Palani Road, Thippampatti, Namakkal District - 637 205. Opp. to Kotturpuram Railway Station, Pollachi - 642 107 Ph: 04288 - 234670 Adyar, Chennai - 600020. Ph: 73737 66550 | 94432 66008 91 94437 34670 Ph: 044 - 24401362 | 044 - 24426913 90951 66009 www.vetriias.com © VETRII IAS STUDY CIRCLE First Edition – 2015 Second Edition – 2019 Pages : 114 Size : (240 × 180) cm Price : 220/- Published by: VETRII IAS STUDY CIRCLE F Block New No. 1, 9th Street, 1st Avenue main Road, Chinthamani, Anna Nagar (E), Chennai – 102. Phone: 044-2626 5326 | 98844 72636 | 98844 21666 | 98844 32666 www.vetriias.com E-mail: [email protected] / [email protected] / [email protected] Feedback: [email protected] © All rights reserved with the publisher. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the written permission of the publisher, will be responsible for the loss and may be punished for compensation under copyright act. -

Social Studies for Secondary Schools

Teaching Guide BOOK We learn Social Studies For Secondary Schools Khadija Chagla-Baig 1 contents Contents Pages Introduction .......................................................................................................................................iv Unit 1 The universe .......................................................................................................................... 2 Unit 2 Maps and globes ................................................................................................................... 6 Unit 3 The Earth ............................................................................................................................. 12 Unit 4 Inside the Earth.................................................................................................................... 16 Unit 5 Natural energy resources..................................................................................................... 20 Unit 6 The Indus Valley Civilization ................................................................................................ 24 Unit 7 The arrival of the Aryans ..................................................................................................... 28 Unit 8 Muslims in Sindh .................................................................................................................. 32 Unit 9 The Muslim Dynasties I ....................................................................................................... 34 Unit 10 The Muslim Dynasties II -

The Rise of Dalit Peasants Kolhi Activism in Lower Sindh

The Rise of Dalit Peasants Kolhi Activism in Lower Sindh (Original Thesis Title) Kolhi-peasant Activism in Naon Dumbālo, Lower Sindh Creating Space for Marginalised through Multiple Channels Ghulam Hussain Mahesar Quaid-i-Azam University Department of Anthropology ii Islamabad - Pakistan Year 2014 Kolhi-Peasant Activism in Naon Dumbālo, Lower Sindh Creating Space for Marginalised through Multiple Channels Ghulam Hussain Thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology, Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad, in partial fulfillment of the degree of ‗Master of Philosophy in Anthropology‘ iii Quaid-i-Azam University Department of Anthropology Islamabad - Pakistan Year 2014 Formal declaration I hereby, declare that I have produced the present work by myself and without any aid other than those mentioned herein. Any ideas taken directly or indirectly from third party sources are indicated as such. This work has not been published or submitted to any other examination board in the same or a similar form. Islamabad, 25 March 2014 Mr. Ghulam Hussain Mahesar iv Final Approval of Thesis Quaid-i-Azam University Department of Anthropology Islamabad - Pakistan This is to certify that we have read the thesis submitted by Mr. Ghulam Hussain. It is our judgment that this thesis is of sufficient standard to warrant its acceptance by Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad for the award of the degree of ―MPhil in Anthropology‖. Committee Supervisor: Dr. Waheed Iqbal Chaudhry External Examiner: Full name of external examiner incl. title Incharge: Dr. Waheed Iqbal Chaudhry v ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This thesis is the product of cumulative effort of many teachers, scholars, and some institutions, that duly deserve to be acknowledged here.