Politics and Folktale in the Classical World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

Index Note: page numbers in italics denote tables, maps, or illustrations Abdera 74 Cleomenes 237 ; coins 159, 276 , Abu Simbel 297 277, 279 ; food production 121, 268, Abydos 286 272 ; imports 268 ; Kleoitas 109 ; Achaea/Achaeans: Aigialos 213 ; Naucratis 269–271 ; pottery 191 ; basileus 128, 129, 134 ; Sparta 285 ; trade 268, 272 colonization 100, 104, 105, 107–108, Aegium 88, 91, 108 115, 121 ; democracy 204 ; Aelian 4, 186, 188 dialect 44 ; ethnos 91 ; Aeneas 109, 129 Herodotus 91 ; heroes 73, 108 ; Aeolians 45 , 96–97, 122, 292, 307 ; Homer 52, 172, 197, 215 ; dialect group 44, 45, 46 Ionians 50 ; migration 44, 45 , 50, Aeschines 86, 91, 313, 314–315 96 ; pottery 119 ; as province 68 ; Aeschylus: Persians 287, 308 ; Seven relocation 48 ; warrior tombs 49 Against Thebes 162 ; Suppliant Achilles 128, 129, 132, 137, 172, 181, Maidens 204 216 ; shield of 24, 73, 76, 138–139 Aetolia/Aetolians 20 ; dialect 299 ; Acrae 38 , 103, 110 Erxadieis 285 ; ethnos 91, 92 ; Acraephnium 279 poleis 93 ; pottery 50 ; West Acragas 38 , 47 ; democracy 204 ; Locris 20 foundation COPYRIGHTED 104, 197 ; Phalaris 144 ; Aëtos MATERIAL 62 Theron 149, 289 ; tyranny 150 Africanus, Sextus Julius 31 Adrastus 162 Agamemnon: Aeolians 97 ; anax 129 ; Aegimius 50, 51 Argos 182 ; armor 173 ; Aegina 3 ; Argos 3, 5 ; Athens 183, basileus 128, 129 ; scepter 133 ; 286, 287 ; captured 155 ; Schliemann 41 ; Thersites 206 A History of the Archaic Greek World: ca. 1200–479 BCE, Second Edition. Jonathan M. Hall. © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Published 2014 by John Wiley & Sons, -

Herodotus' Conception of Foreign Languages

Histos () - HERODOTUS’ CONCEPTION OF FOREIGN LANGUAGES * Introduction In one of the most famous passages in his Histories , Herodotus has the Athe- nians give the reasons why they would never betray Greece (..): first and foremost, the images and temples of the gods, burnt and requiring vengeance, and then ‘the Greek thing’, being of the same blood and the same language, having common shrines and sacrifices and the same way of life. With race or blood, and with religious cult, language appears as one of the chief determinants of Greek identity. This impression is confirmed in Herodotus’ accounts of foreign peoples: language is—with religious customs, dress, hairstyles, sexual habits—one of the key items on Herodotus’ checklist of similarities and differences with foreign peoples. That language was an important element of what, to a Greek, it meant to be a Greek, should not perhaps be thought surprising. As is well known, the Greeks called non- Greeks βάρβαροι , a term usually taken to refer pejoratively to the babble of * This paper has been delivered in a number of different versions at St. Andrews, Newcastle, and at the Classical Association AGM. I should like to express my thanks to all those who took part in the subsequent discussions, and especially to Robert Fowler, Alan Griffiths, Robert Parker, Anna Morpurgo Davies and Stephanie West for their ex- tremely valuable comments on written drafts, to Hubert Petersmann for kindly sending me offprints of his publications, to Adrian Gratwick for his expert advice on a point of detail, and to David Colclough and Lucinda Platt for the repeated hospitality which al- lowed me to undertake the bulk of the research. -

From Sacrilege to Violence

From Sacrilege to Violence The Rape of Cassandra on Attic Vases c. 575-400 BCE by Janke du Preez Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Dr Samantha Masters March 2020 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. March 2020 Copyright © 2020 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract The Sack of Troy or Ilioupersis, is a lost epic of ancient Greek literature which tells of the violent and ruthless Greeks that pillaged the city of Troy. It was a prevalent theme in ancient Attic art, and in the fifth century BCE evolved onto the platform of Athenian drama. The Rape of Cassandra episode is one of the most recurring scenes in Attic vase-painting. The iconography, however, dramatically changes between 575-400 BCE. Both Archaic black-figure and Classical red-figure examples show Cassandra, in a vulnerable position, being attacked by Ajax. However, there are significant differences between the iconography of scenes from these two periods. In Archaic black-figure vase-painting the figure of Cassandra appears small, insignificant and in some instances completely hidden from view as she is obscured by the huge shield of Athena. -

1 from City-State to Region-State

The Athenian Experiment: Building an Imagined Political Community in Ancient Attica, 508-490 B.C. Greg Anderson http://www.press.umich.edu/titleDetailDesc.do?id=17798 The University of Michigan Press 1 FROM CITY-STATE TO REGION-STATE What exactly do we mean when we say that Attica in the classical period was politically “incorporated” or “uniµed”? If, for the purposes of analysis, we unpack the idea of the polis, we can distinguish three essential levels or sources of political unity in the Attic peninsula. First and most fundamental, the reach of Athenian state institutions ex- tended to the territorial limits of Attica, and this apparatus was recognized as the ultimate locus of political authority for the entire region. Second, all free, native-born, adult males in Attica were eligible to become citizens of Athens, entitling them—even obliging them—to participate in the civil, military, and religious life of the polis. From / on, enrollment took place locally in one of town and village units, or demes, scattered throughout the peninsula and was administered by one’s fellow demesmen. Third, despite the unusually large size of the polis, citizens appear to have been bound to one another by a pow- erful and at times distinctly chauvinistic form of collective consciousness or identity. Each citizen was encouraged to imagine himself a member of a sin- gle, extended, undifferentiated community of “Athenians,” sharing with his fellows a common history, culture, and destiny that set them apart from all other such communities. For most modern authorities, these distinctions will seem artiµcial and per- haps anachronistic, since it is widely felt that, unlike the nation-states of our own times, the Greek polis in general and the Athenian instance in particular 13 The Athenian Experiment: Building an Imagined Political Community in Ancient Attica, 508-490 B.C. -

Herodotus and the Origins of Political Philosophy the Beginnings of Western Thought from the Viewpoint of Its Impending End

Herodotus and the Origins of Political Philosophy The Beginnings of Western Thought from the Viewpoint of its Impending End A doctoral thesis by O. H. Linderborg Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Engelska Parken, 7-0042, Thunbergsvägen 3H, Uppsala, Monday, 3 September 2018 at 14:00 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Docent Elton Barker (Open University). Abstract Linderborg, O. H. 2018. Herodotus and the Origins of Political Philosophy. The Beginnings of Western Thought from the Viewpoint of its Impending End. 224 pp. Uppsala: Department of Linguistics and Philology, Uppsala University. ISBN 978-91-506-2703-9. This investigation proposes a historical theory of the origins of political philosophy. It is assumed that political philosophy was made possible by a new form of political thinking commencing with the inauguration of the first direct democracies in Ancient Greece. The pristine turn from elite rule to rule of the people – or to δημοκρατία, a term coined after the event – brought with it the first ever political theory, wherein fundamentally different societal orders, or different principles of societal rule, could be argumentatively compared. The inauguration of this alternative-envisioning “secular” political theory is equaled with the beginnings of classical political theory and explained as the outcome of the conjoining of a new form of constitutionalized political thought (cratistic thinking) and a new emphasis brought to the inner consistency of normative reasoning (‘internal critique’). The original form of political philosophy, Classical Political Philosophy, originated when a political thought launched, wherein non-divinely sanctioned visions of transcendence of the prevailing rule, as well as of the full range of alternatives disclosed by Classical Political Theory, first began to be envisioned. -

The Origin of Tyranny Cambridge University Press C

THE ORIGIN OF TYRANNY CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS C. F. CLAY, MANAGER LONDON : FETTER LANE, E.G. 4 NEW YORK : THE MACMILLAN CO. BOMBAY I CALCUTTAV MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD. MADRAS I TORONTO : THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, LTD. TOKYO: MARUZEN-KABUSH1KI-KAISHA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THE ORIGIN OF TYRANNY BY P. N. URE, M.A. GONVILLE AND CAIUS COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE PROFESSOR OF CLASSICS, UNIVERSITY COLLEGE, READING CAMBRIDGE AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS 1922 be 86. Ul DINTED !N GREAT PREFACE views expressed in the following chapters were first published THEin the Journal of Hellenic Studies for 1906 in a short paper which gave a few pages each to Samos and Athens and a few sentences each to Lydia, Miletus, Ephesus, Argos, Corinth, and Megara. The chapters on Argos, Corinth, and Rome are based on papers read to the Oxford Philological Society in 1913 and to the Bristol branch of the Classical Association in 1914. As regards the presentation of my material here, it has been my endeavour to make the argument intelligible to readers who are not classical scholars and archaeologists. The classics have ceased to be a water-tight compartment in the general scheme of study and research, and my subject forms a chapter in general economic history which might interest students of that subject who are not classical scholars. On the other hand classical studies have become so specialised and the literature in each department has multiplied so enormously that unless monographs can be made more or less complete in them- selves and capable of being read without referring to a large number of large and inaccessible books, it will become impossible for classical scholars to follow the work that is being done even in their own subject beyond the limits of their own particular branch. -

Reading the Rise of Pisistratus: Herodotus .-

Histos () - READING THE RISE OF PISISTRATUS: HERODOTUS .- Especially Sophocles and Herodotus were passionately interested in the manifold aspects of ‘power’, which they interpreted through myth and his- tory, using these in their full topical potential to analyze questions of great importance to their audiences. This paper analyzes Herodotus’ story of Pisistratus’ rise to tyranny over the Athenians in these terms. The story is mythic history in the sense that it is largely made up of conventional narrative episodes, sometimes with su- pernatural elements. Yet the contexts of power in which Herodotus sets it determine its shape, and the contextual reading of the story reveals allusions to contemporary debates and realities. This contextual analysis seems more productive than attempts to explain the story in isolation as the product of Athenian propaganda in a narrow sense. The immediate context for the story of the rise of Pisistratus and of the rise of Sparta that partners it is the comparison of their ancestral power. He- rodotus investigates their origins and their power in the time of Croesus, comparing the Athenians under tyranny with the Spartans under Lycurgan eunomia . Croesus in his search for the ‘most powerful’ of the Greeks as his ally against Persia found out that Athens and Sparta were from their origins leaders respectively of the Ionians and the Dorians (..), but that their I am grateful to the Histos team for detailed comments and practical suggestions on presentation. Raaflaub () , also -. Gray () touches on the question of a standard typology of the tyrant, arguing that the profile of any one tyrant is dictated by the context in which he is presented. -

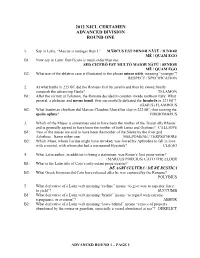

2012 Njcl Certamen Advanced Division Round One

2012 NJCL CERTAMEN ADVANCED DIVISION ROUND ONE 1. Say in Latin, “Marcus is younger than I.” MĀRCUS EST MINOR NĀTŪ / IUNIOR MĒ / QUAM EGO B1: Now say in Latin: But Cicero is much older than me. SED CICERŌ EST MULTŌ MAIOR NĀTŪ / SENIOR MĒ / QUAM EGO B2: What use of the ablative case is illustrated in the phrase minor nātū, meaning “younger”? RESPECT / SPECIFICATION 2. At what battle in 225 BC did the Romans first by javelin and then by sword finally vanquish the advancing Gauls? TELAMON B1: After the victory at Telamon, the Romans decided to counter-invade northern Italy. What general, a plebeian and novus homō, first successfully defeated the Insubrēs in 223 BC? (GAIUS) FLAMINIUS B2: What Insubrian chieftain did Marcus Claudius Marcellus slay in 222 BC, thus earning the spolia opīma? VIRIDOMARUS 3. Which of the Muses is sometimes said to have been the mother of the Trojan ally Rhesus and is generally agreed to have been the mother of both Linus and Orpheus? CALLIOPE B1: Two of the muses are said to have been the mother of the Sirens by the river god Achelous. Name either one. MELPOMENE / TERPSICHORE B2: Which Muse, whom Tacitus might have invoked, was forced by Aphrodite to fall in love with a mortal, with whom she had a son named Hyacinth? CL(E)IO 4. What Latin author, in addition to being a statesman, was Rome’s first prose writer? (MARCUS PORCIUS) CATO THE ELDER B1: What is the Latin title of Cato’s only extant prose treatise? DĒ AGRĪ CULTŪRĀ / DĒ RĒ RUSTICĀ B2: What Greek historian did Cato have released after he was captured by the Romans? POLYBIUS 5. -

Tales of the Greek Heroes Answer Key Level 7

TALES OF THE GREEK HEROES ANSWER KEY LEVEL 7 Before-reading questions 6 He teaches them how to make wine out 1 Reader’s own answer. of grapes 2 Reader’s own answers. 3 Reader’s own answers. CHAPTERS SEVEN, EIGHT AND NINE 4 Reader’s own answers. 1 He tells him to fetch the head of Medusa the Gorgon knowing that he will probably die trying During-reading questions to do this. 2 He takes their one eye and will not give it CHAPTERS ONE, TWO AND THREE back until they tell him where they live. 1 Because Greece is so beautiful they thought 3 He uses the head of Medusa to turn the sea that there must have been gods and fairies monster into stone. Next, they get married. looking after everything. 4 Because he thinks that she will be the mother of 2 The humans of the Golden Age all die because the great Hero he is searching for. no children are born, and the humans of the 5 Because he wants to punish Hera after she Silver Age are evil so Zeus locks them up in uses her powers to make a baby boy called Tartarus with the Titans. Eurystheus come into the world before Heracles, 3 Reader’s own answers. and because of a promise made by Zeus, he will 4 Because he wants them to be different to rule over the people of Argolis and not Heracles. the gods and be able to live independently 6 She asks an old man called Tiresias, who is of them. -

Anthropomorphism, Theatre, Epiphany: from Herodotus to Hellenistic Historians Renée Koch Piettre

Anthropomorphism, Theatre, Epiphany: From Herodotus to Hellenistic Historians Renée Koch Piettre To cite this version: Renée Koch Piettre. Anthropomorphism, Theatre, Epiphany: From Herodotus to Hellenistic His- torians. Archiv für Religionsgeschichte, De Gruyter, 2018, pp.189-209. 10.1515/arege-2018-0012. halshs-02433986 HAL Id: halshs-02433986 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02433986 Submitted on 9 Jan 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Renée Koch Piettre Anthropomorphism, Theatre, Epiphany: From Herodotus to Hellenistic Historians Abstract: This paper argues that, beginning with the Euripidean deus ex machina, dramatic festivals introduced a new standard into epiphanic rituals and experience. Through the scenic double énonciation, gods are seen by mythical heroes as gods, but by the Athenian spectators as costumed actors and fictive entities. People could scarcely believe these were ‘real’ gods, but would have no doubt been im- pressed by the scenic machinery. Thus the Homeric theme of a hero’s likeness to the gods developed into the Hellenistic theme of the godlike ruler’s (or actor’s) the- atrical success (or deceit). So in the Athenians’ Hymn to Demetrius Poliorcetes, a vic- torious ruler entering a city is welcomed as a better god than the gods themselves. -

Homer's Odyssey (1911)

HOMERS ODTSSET HOMER'S ODYSSEY " Flashing she fell to the earth from THE GLITTERING HEIGHTS OF OlYMI - Eco HOMER'S ODYSSEY A LINE^FOR-LINE TRANSLATION IN THE METRE OF THE ORIGINAL BY H, B, COTTERILL M.A. EDITOR OF "SELECTIONS FROM THE INFERNO" GOETHE'S "1PHIGENIE" MILTON'S " AREOPAGITICA " MORE'S "UTOPIA" VIRGIL'S "AENE1D" I & VI ETC WITH TWENTY-FOUR ILLUSTRATIONS BY PATTEN WILSON %c I 4 y LONDON : GEORGE G. HARRAP & COMPANY 9 PORTSMOUTH STREET KINGSWAY W.C. MCMXI PRINTED BY BALLANTYNE & COMPANY LTD AT THE BALLANTYNE PRESS TAVISTOCK ST. COVENT GARDEN LONDON TO MY WIFE AND DAUGHTER AND TO ALL THOSE WHOSE LOVE FOR HOMER AND FOR WHATEVER ELSE IN ART IS TRUE AND BEAUTI- FUL GAVE ME THE COURAGE TO UNDERTAKE AND THE ENDURANCE TO COMPLETE THIS VERSION OF THE ODYSSEY * dvr<o "Hroi /xef ttoX\o>v embevofiai dXAd fioi aef-ovatv ii >* i 6(oi, a> "Epyuv fi'if t entfiifJivu). PREFACE 'N his Lectures on Translating Homer Matthew Arnold advises the translator to Preface have nothing to do with side questions—such as the question whether Homer ever existed. I should rather say that, however much interest he may take in antiquarian, or philological, or other side questions, it is best for him to give .a wide berth to theoretics and polemics. Indeed, if the translator is one who ' fulfils Matthew Arnold's requirements by reading Homer perpetually for the ' sake of his poetry — if he has experienced the happiness of long and continuous intimacy with what is so beautiful and so restful—he will shrink with pain the Babel of feel from and the acrimony literary disputation, and will much inclined to say nothing at all, knowing full well that, whatever he may say or may leave unsaid, his work will have to speak for itself. -

Greco-Roman Mythology Overview

Cyclopaedia 26 – Greco-Roman Mythology By T.R. Knight (InnRoads Ministries * Article Series) Overview Creatures and Monsters of Mythology Most likely, you studied Classical Mythology, also called Greco-Roman Mythology, in Greco-Roman Mythology depicts more than school. You read about the various Greek and just gods and demi-gods. There is an entire Roman gods that inspired storytellers and ecosystem of unique creatures and poets to write some of the great epics and monsters. Many of them exist in similar tragedies. These myths began as oral forms, sometimes with different names, in traditions, then were late compiled into other mythologies and folklore. Greek and Latin writings. • Argus These myths related the Greek and Roman • Centaur religions, concerned with the actions of gods, • Cerberus supernatural creatures, and the heroes • Cetus influenced by the gods. The most famous of • Chimera these were written by Homer, the Iliad and • Colchian Dragon the Odyssey. • Cyclops • Echidna The Romans adapted the myths of the • Griffin Greeks, importing many into their own • Harpy legends and stories, creating counterparts. • Hecatoncheires Thus, you find Ares mirrored in Mars as the • Lamia war god, and many gods and demigods with • Lernaean Hydra matching legends but different names. • Medusa • Minotaur Cinema latched onto these myths as • Myrmekes Indikoi storylines because of their fantastic tales, • Pegasus epic settings, and over-the-top heroes. The • Satyr films were so popular, a cheaper subgenre • Scylla emerged called peplum, or more commonly • called sword-and-sandal, which were a mix of Sphinx lower budget Biblical or Mythology based • Triton films. • Typhon Classical Mythology still fascinates us today, Following are sources of information spawning new book series, movies of epic pertaining to Greco-Roman Mythology to heroes, and games that let us step into the assist prospective game masters, game role of mythical heroes and gods.