From Tyranny to Democracy Prescribed Source Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historically Speaking

Historically Speaking Marathon at 2,500 ugust 12 marks an accepted date for By BG John S. Brown Greeks recently conquered by Persia rose the 2,500th anniversary of the Battle in revolt. Athens and the tiny city-state of A U.S. Army retired of Marathon, although the actual date Eretria attempted to assist, but the Per- may instead be September 12, depending upon how one sians utterly crushed the Ionians. Darius resolved to crush interprets the Lacedaemonian lunisolar calendar. The most Athens and Eretria as well and to bring the European Greeks notable commemoration will probably be the Athens into his orbit. Had he succeeded, he would have snuffed out Marathon this year, and other marathons around the world the democratic experiment, independent Hellenic civiliza- will undoubtedly take notice as well. Ironically, the ardu- tion and Greek national identity with a single stroke. ous 26-mile race is based upon an athletic performance by After preliminary operations in Thrace and Macedonia, the legendary Philippides that may not have actually oc- Darius launched a naval expedition directly across the curred. The battle itself did occur and is rightly regarded Aegean Sea. Securing—or devastating—islands en route, as among the most decisive in history. Marathon is ar- the Persians sacked Eretria and landed an army more than guably the first major battle for which we have a reliable twice the size of what Athens could muster in the sheltered record, provided largely by the world’s first actual histo- Bay of Marathon. Hippias recommended the spot, both be- rian, Herodotus. -

Who Freed Athens? J

Ancient Greek Democracy: Readings and Sources Edited by Eric W. Robinson Copyright © 2004 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd The Beginnings of the Athenian Democracv: Who Freed Athens? J Introduction Though the very earliest democracies lildy took shape elsewhere in Greece, Athens embraced it relatively early and would ultimately become the most famous and powerful democracy the ancient world ever hew. Democracy is usually thought to have taken hold among the Athenians with the constitutional reforms of Cleisthenes, ca. 508/7 BC. The tyrant Peisistratus and later his sons had ruled Athens for decades before they were overthrown; Cleisthenes, rallying the people to his cause, made sweeping changes. These included the creation of a representative council (bode)chosen from among the citizens, new public organizations that more closely tied citizens throughout Attica to the Athenian state, and the populist ostracism law that enabled citizens to exile danger- ous or undesirable politicians by vote. Beginning with these measures, and for the next two centuries or so with only the briefest of interruptions, democracy held sway at Athens. Such is the most common interpretation. But there is, in fact, much room for disagree- ment about when and how democracy came to Athens. Ancient authors sometimes refer to Solon, a lawgiver and mediator of the early sixth century, as the founder of the Athenian constitution. It was also a popular belief among the Athenians that two famous “tyrant-slayers,” Harmodius and Aristogeiton, inaugurated Athenian freedom by assas- sinating one of the sons of Peisistratus a few years before Cleisthenes’ reforms - though ancient writers take pains to point out that only the military intervention of Sparta truly ended the tyranny. -

The Tradition of Ancient Greek Democracy and Its Importance for Modem Democracy

DEMOCRAC AHMOKPATI The Tradition of Ancient Greek Democracy and its Importance for Modern Democracy Mogens Herman Hansen The Tradition of Ancient Greek Democracy and its Importance for Modem Democracy B y M ogens H erman H ansen Historisk-filosofiske Meddelelser 93 Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab The Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters Copenhagen 2005 Abstract The two studies printed here investigate to what extent there is a con nection between ancient and modem democracy. The first study treats the tradition of ancient Greek democracy, especially the tradition of Athenian democracy from ca. 1750 to the present day. It is argued that in ideology there is a remarkable resemblance between the Athenian democracy in the Classical period and the modem liberal democracy in the 19th and 20th centuries. On the other hand no direct tradition con nects modem liberal democracy with its ancient ancestor. Not one single Athenian institution has been copied by a modem democracy, and it is only from ca. 1850 onwards that the ideals cherished by the Athenian democrats were referred to approvingly by modem cham pions of democracy. It is in fact the IT technology and its potential for a return to a more direct form of democracy which has given rise to a hitherto unmatched interest in the Athenian democratic institutions. This is the topic of the second study in which it is argued that the focus of the contemporary interest is on the Athenian system of sortition and rotation rather than on the popular assembly. Contents The Tradition of Democracy from Antiquity to the Present Time ................................................................. -

The Olynthiacs and the Phillippics of Demosthenes

The Olynthiacs and the Phillippics of Demosthenes Charles Rann Kennedy The Olynthiacs and the Phillippics of Demosthenes Table of Contents The Olynthiacs and the Phillippics of Demosthenes..............................................................................................1 Charles Rann Kennedy...................................................................................................................................1 THE FIRST OLYNTHIAC............................................................................................................................1 THE SECOND OLYNTHIAC.......................................................................................................................6 THE THIRD OLYNTHIAC........................................................................................................................10 THE FIRST PHILIPPIC..............................................................................................................................14 THE SECOND PHILIPPIC.........................................................................................................................21 THE THIRD PHILIPPIC.............................................................................................................................25 THE FOURTH PHILIPPIC.........................................................................................................................34 i The Olynthiacs and the Phillippics of Demosthenes Charles Rann Kennedy This page copyright © 2002 Blackmask Online. -

Herodotus' Conception of Foreign Languages

Histos () - HERODOTUS’ CONCEPTION OF FOREIGN LANGUAGES * Introduction In one of the most famous passages in his Histories , Herodotus has the Athe- nians give the reasons why they would never betray Greece (..): first and foremost, the images and temples of the gods, burnt and requiring vengeance, and then ‘the Greek thing’, being of the same blood and the same language, having common shrines and sacrifices and the same way of life. With race or blood, and with religious cult, language appears as one of the chief determinants of Greek identity. This impression is confirmed in Herodotus’ accounts of foreign peoples: language is—with religious customs, dress, hairstyles, sexual habits—one of the key items on Herodotus’ checklist of similarities and differences with foreign peoples. That language was an important element of what, to a Greek, it meant to be a Greek, should not perhaps be thought surprising. As is well known, the Greeks called non- Greeks βάρβαροι , a term usually taken to refer pejoratively to the babble of * This paper has been delivered in a number of different versions at St. Andrews, Newcastle, and at the Classical Association AGM. I should like to express my thanks to all those who took part in the subsequent discussions, and especially to Robert Fowler, Alan Griffiths, Robert Parker, Anna Morpurgo Davies and Stephanie West for their ex- tremely valuable comments on written drafts, to Hubert Petersmann for kindly sending me offprints of his publications, to Adrian Gratwick for his expert advice on a point of detail, and to David Colclough and Lucinda Platt for the repeated hospitality which al- lowed me to undertake the bulk of the research. -

The Satrap of Western Anatolia and the Greeks

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Eyal Meyer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Eyal, "The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2473. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Abstract This dissertation explores the extent to which Persian policies in the western satrapies originated from the provincial capitals in the Anatolian periphery rather than from the royal centers in the Persian heartland in the fifth ec ntury BC. I begin by establishing that the Persian administrative apparatus was a product of a grand reform initiated by Darius I, which was aimed at producing a more uniform and centralized administrative infrastructure. In the following chapter I show that the provincial administration was embedded with chancellors, scribes, secretaries and military personnel of royal status and that the satrapies were periodically inspected by the Persian King or his loyal agents, which allowed to central authorities to monitory the provinces. In chapter three I delineate the extent of satrapal authority, responsibility and resources, and conclude that the satraps were supplied with considerable resources which enabled to fulfill the duties of their office. After the power dynamic between the Great Persian King and his provincial governors and the nature of the office of satrap has been analyzed, I begin a diachronic scrutiny of Greco-Persian interactions in the fifth century BC. -

Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2016 Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Van Oort, Danielle, "Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal" (2016). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 1016. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. REST, SWEET NYMPHS: PASTORAL ORIGINS OF THE ENGLISH MADRIGAL A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Music History and Literature by Danielle Van Oort Approved by Dr. Vicki Stroeher, Committee Chairperson Dr. Ann Bingham Dr. Terry Dean, Indiana State University Marshall University May 2016 APPROVAL OF THESIS We, the faculty supervising the work of Danielle Van Oort, affirm that the thesis, Rest Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal, meets the high academic standards for original scholarship and creative work established by the School of Music and Theatre and the College of Arts and Media. This work also conforms to the editorial standards of our discipline and the Graduate College of Marshall University. With our signatures, we approve the manuscript for publication. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express appreciation and gratitude to the faculty and staff of Marshall University’s School of Music and Theatre for their continued support. -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

From Sacrilege to Violence

From Sacrilege to Violence The Rape of Cassandra on Attic Vases c. 575-400 BCE by Janke du Preez Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Dr Samantha Masters March 2020 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. March 2020 Copyright © 2020 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract The Sack of Troy or Ilioupersis, is a lost epic of ancient Greek literature which tells of the violent and ruthless Greeks that pillaged the city of Troy. It was a prevalent theme in ancient Attic art, and in the fifth century BCE evolved onto the platform of Athenian drama. The Rape of Cassandra episode is one of the most recurring scenes in Attic vase-painting. The iconography, however, dramatically changes between 575-400 BCE. Both Archaic black-figure and Classical red-figure examples show Cassandra, in a vulnerable position, being attacked by Ajax. However, there are significant differences between the iconography of scenes from these two periods. In Archaic black-figure vase-painting the figure of Cassandra appears small, insignificant and in some instances completely hidden from view as she is obscured by the huge shield of Athena. -

The Phocian Betrayal at Thermopylae

historia 68, 2019/4, 413–435 DOI 10.25162/historia-2019-0022 Jeffrey Rop The Phocian Betrayal at Thermopylae Abstract: This article makes three arguments regarding the Battle of Thermopylae. First, that the discovery of the Anopaea path was not dependent upon Ephialtes, but that the Persians were aware of it at their arrival and planned their attacks at Thermopylae, Artemisium, and against the Phocians accordingly. Second, that Herodotus’ claims that the failure of the Pho- cians was due to surprise, confusion, and incompetence are not convincing. And third, that the best explanation for the Phocian behavior is that they were from Delphi and betrayed their allies as part of a bid to restore local control over the sanctuary. Keywords: Thermopylae – Artemisium – Delphi – Phocis – Medism – Anopaea The courageous sacrifice of Leonidas and the Spartans is perhaps the central theme of Herodotus’ narrative and of many popular retellings of the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BCE. Even as modern historians are appropriately more critical of this heroizing impulse, they have tended to focus their attention on issues that might explain why Leo- nidas and his men fought to the death. These include discussion of the broader strategic and tactical importance of Thermopylae, the inter-relationship and chronology of the Greek defense of the pass and the naval campaign at Artemisium, the actual number of Greeks who served under Leonidas and whether it was sufficient to hold the position, and so on. While this article inevitably touches upon some of these same topics, its main purpose is to reconsider the decisive yet often overlooked moment of the battle: the failure of the 1,000 Phocians on the Anopaea path. -

The Territorial Gains Made by Cambyses in the Eastern Mediterranean

GRAECO-LATINA BRUNENSIA 20, 2015, 1 MICHAL HABAJ (UNIVERSITY OF SS. CYRIL AND METHODIUS, TRNAVA) THE TERRITORIAL GAINS MADE BY CAMBYSES IN THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN The Persian king Cambyses is most often mentioned in the context of his successful expedi- tion to Egypt. Both antique sources and modern scholarly research tend to focus on the suc- cess of Cambyses in Egypt, which is undoubtedly deserved of attention. As a result however, scholarly interest in Cambyses’ other territorial gains is marginal. His successful Egyptian expedition required extensive preparation. For example, one crucial factor was his ability to seize control over the eastern Mediterranean in preparation for the naval part of the campaign. These territorial gains, as well as his control over the sea in the region, inspired Herodotus to refer to Cambyses as ‘the master of the sea’. This is an important epithet which Herodotus grants Cambyses, since it seems to suggest that it was Cambyses who expanded the Persian empire to the eastern Mediterranean. Based on the aforementioned reference by Herodotus, the following study provides an analysis of the process of incorporation of these areas into the Persian Empire, insofar as the sources differ on whether these territories were annexed under Cyrus, Cambyses or Darius. In so doing, the analysis attempts to shed more light on the meaning of Herodotus’ words, and gives an account of Cambyses’ territorial gains in the Mediterranean. Key words: Achaemenid Persia, Cambyses II, Cyprus, Samos, Cilicia, Phoenicia Introduction The Persian king Cambyses is best known for his invasion and subse- quent successful conquest of Egypt. -

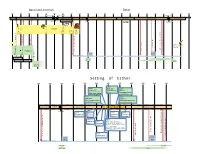

Setting of Esther

Daniel and Jeremiah Esther 610 600 590 580 570 560 550 540 530 520 510 500 490 480 470 460 450 440 430 420 410 400 Amel-marduk 561-560 Labashi-marduk 556 Xerxes II 425-424 Cambyses Nabopolassar Nebuchadnezzar 605-562 Nabonidus 556-536 Cyrus 539-530 Darius I 521-486 Xerxes I 486-465 Artaxerxes I 465-424 Darius II 423-404 625-605 529-522 Nergal-shal-usur 559-557 Belshazzar 553-539 Smerdis 522 ESTHER Sogdianus 424-423 DANIEL 12 - 8 - Dan 3 Dan Dan 2 Dan 4 Dan 7 Dan 6, 9 5, Dan 10 Dan The The statue dream, 604 Fiery furnace, c603 The tree dream, c571 Vision of four beasts, 553 Vision of ram &goat, 551 Fall of Babylon, 539 Lion’s den Reading of Jeremiah, 539 Vision of the end, 536 , 538 , Deportation, Deportation, 605 st 1 Deportation, 597 Deportation, Deportation, 587 Deportation, Sheshbazzar nd rd Letters sent from Jews at 2 3 Elephantine to Yohanan, high priest in Jerusalem, 410 and 407 Nehemiah returned to Artaxerxes, Artaxerxes, 433 Nehemiah toreturned visit of Nehemiah, Nehemiah, 432 visit of visit of Nehemiah, 445 visitof Nehemiah, return, return, led by st nd Return of Ezra, 458 of Return Ezra, 1 2 st JEREMIAH 1 Walls of 29 25 Temple Jerusalem rebuilt Jer Jer Message Message to exiles, 597 Prophecy Prophecy of captivity, 605 rebuilt, Temple foundation laid 520-516 443 Jehoiakim 609-598 HAGGAI NEHEMIAH Jehoiachin 608-597 Zedekiah 597-587 flight585 to Forced Egypt, ZECHARIAH EZRA MALACHI 44 Jer Prophecy Prophecy against refugees in Egypt Setting of Esther 540 530 520 510 500 490 480 470 460 450 440 430 478 BC 482 BC Esther 2:16 474