The Criminal Investigation Process Volume Iii: Observations and Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case Closed, Vol. 27 Ebook Free Download

CASE CLOSED, VOL. 27 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Gosho Aoyama | 184 pages | 29 Oct 2009 | Viz Media, Subs. of Shogakukan Inc | 9781421516790 | English | San Francisco, United States Case Closed, Vol. 27 PDF Book January 20, [22] Ai Haibara. Views Read Edit View history. Until Jimmy can find a cure for his miniature malady, he takes on the pseudonym Conan Edogawa and continues to solve all the cases that come his way. The Junior Detective League and Dr. Retrieved November 13, January 17, [8]. Product Details. They must solve the mystery of the manor before they are all killed off or kill each other. They talk about how Shinichi's absence has been filled with Dr. Chicago 7. April 10, [18] Rachel calls Richard to get involved. Rachel thinks it could be the ghost of the woman's clock tower mechanic who died four years prior. Conan's deductions impress Jodie who looks at him with great interest. Categories : Case Closed chapter lists. And they could have thought Shimizu was proposing a cigarette to Bito. An unknown person steals the police's investigation records relating to Richard Moore, and Conan is worried it could be the Black Organization. The Junior Detectives find the missing boy and reconstruct the diary pages revealing the kidnapping motive and what happened to the kidnapper. The Junior Detectives meet an elderly man who seems to have a lot on his schedule, but is actually planning on committing suicide. Magic Kaito Episodes. Anime News Network. Later, a kid who is known to be an obsessive liar tells the Detective Boys his home has been invaded but is taken away by his parents. -

Protoculture Addicts

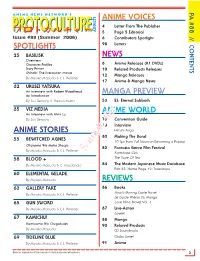

PA #88 // CONTENTS PA A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S ANIME VOICES 4 Letter From The Publisher PROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]-PROTOCULTURE ADDICTS 5 Page 5 Editorial Issue #88 (Summer 2006) 6 Contributors Spotlight SPOTLIGHTS 98 Letters 25 BASILISK NEWS Overview Character Profiles 8 Anime Releases (R1 DVDs) Story Primer 10 Related Products Releases Shinobi: The live-action movie 12 Manga Releases By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 17 Anime & Manga News 32 URUSEI YATSURA An interview with Robert Woodhead MANGA PREVIEW An Introduction By Zac Bertschy & Therron Martin 53 ES: Eternal Sabbath 35 VIZ MEDIA ANIME WORLD An interview with Alvin Lu By Zac Bertschy 73 Convention Guide 78 Interview ANIME STORIES Hitoshi Ariga 80 Making The Band 55 BEWITCHED AGNES 10 Tips from Full Moon on Becoming a Popstar Okusama Wa Maho Shoujo 82 Fantasia Genre Film Festival By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Sample fileKamikaze Girls 58 BLOOD + The Taste Of Tea By Miyako Matsuda & C. Macdonald 84 The Modern Japanese Music Database Part 35: Home Page 19: Triceratops 60 ELEMENTAL GELADE By Miyako Matsuda REVIEWS 63 GALLERY FAKE 86 Books Howl’s Moving Castle Novel By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Le Guide Phénix Du Manga 65 GUN SWORD Love Hina, Novel Vol. 1 By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 87 Live-Action Lorelei 67 KAMICHU! 88 Manga Kamisama Wa Chugakusei 90 Related Products By Miyako Matsuda CD Soundtracks 69 TIDELINE BLUE Otaku Unite! By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 91 Anime More on: www.protoculture-mag.com & www.animenewsnetwork.com 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ LETTER FROM THE PUBLISHER A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S PROTOCULTUREPROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]- ADDICTS Over seven years of writing and editing anime reviews, I’ve put a lot of thought into what a Issue #88 (Summer 2006) review should be and should do, as well as what is shouldn’t be and shouldn’t do. -

Access to Justice for Children: Mexico

ACCESS TO JUSTICE FOR CHILDREN: MEXICO This report was produced by White & Case LLP in November 2013 but may have been subsequently edited by Child Rights International Network (CRIN). CRIN takes full responsibility for any errors or inaccuracies in the report. I. What is the legal status of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC)? A. What is the status of the CRC and other relevant ratified international instruments in the national legal system? The CRC was signed by Mexico on 26 January 1990, ratified on 21 November 1990, and published in the Federal Official Gazette (Diario Oficial de la Federación) on 25 January 1991. In addition to the CRC, Mexico has ratified the Optional Protocols relating to the involvement of children in armed conflict and the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography. All treaties signed by the President of Mexico, with the approval of the Senate, are deemed to constitute the supreme law of Mexico, together with the Constitution and the laws of the Congress of the Union.1 The CRC is therefore part of national law and may serve as a legal basis in any proceedings before the national courts. It is also part of the supreme law of Mexico as a whole and must be implemented at federal level and in all the individual states.2 B. Does the CRC take precedence over national law The CRC has been interpreted to take precedence over national laws, but not the Constitution. According to doctrinal thesis LXXVII/99 of November 1999, international treaties are ranked second immediately after the Constitution and ahead of federal and local laws.3 On several occasions, Mexico’s Supreme Court has stated that international treaties take precedence over national law, mainly in the case of human rights.4 C. -

Criminal Procedure in Perspective Kit Kinports

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 98 Article 3 Issue 1 Fall Fall 2007 Criminal Procedure in Perspective Kit Kinports Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Kit Kinports, Criminal Procedure in Perspective, 98 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 71 (2007-2008) This Criminal Law is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 0091-4169/07/9801-0071 THE JOURNALOF CRIMINAL LAW & CRIMINOLOGY Vol, 98, No. I Copyright 0 2008 by Northwestern University, School of Law Printed in U.S.A. CRIMINAL PROCEDURE IN PERSPECTIVE KIT KINPORTS* This Article attempts to situate the Supreme Court's constitutional criminal procedure jurisprudence in the academic debates surrounding the reasonable person standard, in particular, the extent to which objective standards should incorporate a particular individual's subjective characteristics. Analyzing the Supreme Court's search and seizure and confessions opinions, Ifind that the Court shifts opportunisticallyfrom case to case between subjective and objective tests, and between whose point of view-the police officer's or the defendant's-it views as controlling. Moreover, these deviations cannot be explained either by the principles the Court claims underlie the various constitutionalprovisions at issue or by the attributes of subjective and objective tests themselves. The Article then centers on the one Supreme Court opinion in this area to address the question of "subjective" objective standards, Yarborough v. -

Factsheet: Pre-Trial Detention

Detention Monitoring Tool Factsheet Pre-trial detention Addressing risk factors to prevent torture and ill-treatment ‘Long periods of pre-trial custody contribute to overcrowding in prisons, exacerbating the existing problems as regards conditions and relations between the detainees and staff; they also add to the burden on the courts. From the standpoint of preventing ill-treatment, this raises serious concerns for a system already showing signs of stress.’ (UN Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture)1 1. Definition and context 2. What are the main standards? Remand prisoners are detained during criminal Because of its severe and often irreversible negative investigations and pending trial. Pre-trial detention is effects, international law requires that pre-trial not a sanction, but a measure to safeguard a criminal detention should be the exception rather than the procedure. rule. At any one time, an estimated 3.2 million people are Pre-trial detention is only legitimate where there is a behind bars awaiting trial, accounting for 30 per cent reasonable suspicion of the person having committed of the total prison population worldwide. They are the offence, and where detention is necessary and legally presumed innocent until proven guilty but may proportionate to prevent them from absconding, be held in conditions that are worse than those for committing another offence, or interfering with the convicted prisoners and sometimes for years on end. course of justice during pending procedures. This means that pre-trial detention is not legitimate where Pre-trial detention undermines the chance of a fair these objectives can be achieved through other, less trial and the presumption of innocence. -

Questioning a Charged Suspect

QUESTIONING A CHARGED SUSPECT "The police have an interest in investigating new or additional crimes after an individual is formally charged with one crime."(1) After a suspect has been arrested for one crime, officers who are investigating another crime may want to question him. In fact, this happens a lot because for some people committing crime is a way of life. They may be career criminals, they may have gone on a crime spree, or they may just commit crimes whenever it suits their purposes. In any event, when they are eventually arrested for one of their crimes, officers who are investigating other crimes may be lined up, waiting to question them. Can they lawfully do so? The answer depends mainly on whether the suspect has been charged with the crime that will be the subject of interrogation. If not, officers will ordinarily be free to question him so long as they comply with Miranda. On the other hand, if the suspect has been charged, officers must also comply with a set of rules that come from an area of law known as the Sixth Amendment right to counsel. Under the Sixth Amendment a suspect has a right to have counsel present whenever he is questioned about a crime with which he has been charged.(2) As we will explain, the suspect may, however, waive this right or he may invoke it. Although this may sound a lot like Miranda, it is quite different. For example, Miranda and Sixth Amendment rights attach at different times during an investigation, they are invoked in different ways, and the consequences of an invocation differ. -

If You Are Suspected of a Criminal Offence If You Are Suspected of a Criminal Offence

If you are suspected of a criminal offence If you are suspected of a criminal offence Contents About this brochure 3 Arrest and questioning 3 Police custody 3 Your lawyer 4 The Probation Service 5 Rights and restrictions 5 Appearance before the Officer of Justice 6 What happens next? 6 Detention 7 Remand 7 Release 8 Preliminary hearing 9 Prosecution 10 Dismissal 10 In court 10 Compensation 11 Assistance 12 Other brochures 13 Further information 13 2 If you are suspected of a criminal offence About this brochure This brochure provides information about what to expect if you have been arrested for a criminal offence. It explains the role of the various people involved in the criminal justice system, how long you can be held in custody or on remand, and sets out your rights and responsibilities. It also tells you where you can obtain further information at each stage of the procedure. You can also contact your own lawyer or the local office of the Juridisch Loket (Legal Advice Centre). Details of other brochures and useful addresses are given at the rear of this brochure. Arrest and questioning You have been arrested on suspicion of having committed a criminal offence. The police may wish to question you further at the police station. If so, they are entitled to hold you for up to six ‘working’ hours. The hours between midnight and 9 am do not count towards this period. For example, if you are taken to the police station at 9 o’ clock in the evening, the police can detain you for questioning until 12 noon the following day. -

14-1096 Luna Torres V. Lynch (05/19/2016)

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2015 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus LUNA TORRES v. LYNCH, ATTORNEY GENERAL CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT No. 14–1096. Argued November 3, 2015—Decided May 19, 2016 Any alien convicted of an “aggravated felony” after entering the United States is deportable, ineligible for several forms of discretionary re- lief, and subject to expedited removal. 8 U. S. C. §§1227(a)(2)(A)(iii), (3). An “aggravated felony” is defined as any of numerous offenses listed in §1101(a)(43), each of which is typically identified either as an offense “described in” a specific federal statute or by a generic la- bel (e.g., “murder”). Section 1101(a)(43)’s penultimate sentence states that each enumerated crime is an aggravated felony irrespec- tive of whether it violates federal, state, or foreign law. Petitioner Jorge Luna Torres (Luna), a lawful permanent resident, pleaded guilty in a New York court to attempted third-degree arson. When immigration officials discovered his conviction, they initiated removal proceedings. The Immigration Judge determined that Luna’s arson conviction was for an “aggravated felony” and held that Luna was therefore ineligible for discretionary relief. -

Crimes and Criminal Procedure—Appeals Of

Crimes and Criminal Procedure—Appeals of Municipal Court and District Magistrate Judgments; Search Warrants; Reporting of Pornographic Materials Seized or Documented as Evidence; Sub. for HB 2017 Sub. for HB 2017 amends provisions of the Kansas Code of Criminal Procedure concerning appeals of municipal court and district magistrate judgments, search warrants, and reporting of pornographic materials seized or documented as evidence. Municipal Court and District Magistrate Judgments The bill amends the law concerning appeals to the district court of municipal court judgments and judgments of a district magistrate judge to provide that these appeals can be filed only after the sentence has been imposed. Further, the bill provides no appeal can be taken more than 14 days after the sentence is imposed. Search Warrants Previously, all search warrants were required to be supported by facts sufficient to show probable cause that a crime has been or is being committed. The bill allows for a warrant to be issued based on probable cause that a crime is about to be committed and makes other technical amendments applicable to all search warrants. Further, the bill adds language specific to search warrants for tracking devices, allowing a magistrate to issue a search warrant for the installation, maintenance, and use of a tracking device. The warrant authorizes use of the device to track and collect tracking data relating to a person or property for a specified time period, but no more than 30 days from installation. The bill defines “tracking device” and “tracking data.” For good cause shown, the warrant can authorize retrieval of tracking data recorded during the specified time period within a reasonable time after the warrant expires, and the magistrate can authorize one or more extensions of the warrant of no more than 30 days each. -

Criminal Procedure Code of the Republic of Armenia

(not official copy) CRIMINAL PROCEDURE CODE OF THE REPUBLIC OF ARMENIA GENERAL PART Section One : GENERAL PROVISIONS CHAPTER 1. LEGISLATION ON CRIMINAL PROCEDURE Article 1. Legislation Governing Criminal Proceedings Article 2. Objectives of the Criminal-Procedure Legislation Article 3. Territory of Effect of the Criminal-procedure Law Article 4. Effect of the Criminal-Procedure Law in the Course of Time Article 5. Peculiarities in the Effect of the Criminal-Procedure Law Article 6. Definitions of the Basic Notions Used in the Criminal-procedure Code CHAPTER 2. PRINCIPLES OF CRIMINAL PROCEEDINGS Article 7. Legitimacy Article 8. Equality of All Before the Law Article 9. Respect for the Rights, Freedoms and Dignity of an Individual Article 10. Ensuring the Right to Legal Assistance Article 11. Immunity of Person Article 12. Immunity of Residence Article 13. Security of Property Article 14. Confidentiality of Correspondence, Telephone Conversations, Mail, Telegraph and Other Communications Article 15. Language of Criminal Proceedings Article 16. Public Trial Article 17. Fair Trial Article 18. Presumption of Innocence Article 19. The Right to Defense of the Suspect and the Accused and Guarantees for this Right Article 20. Privilege Against Self-Incrimination (not official copy) Article 21. Inadmissibility of Repeated Conviction and Criminal Prosecution for the Same Crime Article 22. Rehabilitation of the Rights of the Persons who suffered from Judicial Mistakes Article 23. Adversarial System of Criminal Proceedings Article 24. Administration of Justice Exclusively by the Court Article 25. Independent Assessment of Evidence CHAPTER 3. CONDUCT OF CRIMINAL CASE Article 26. Conduct of Criminal Case Article 27. The Obligation to institute a criminal case and resolution of the crime Article 28. -

Case Closed (Surrealistic Horror Story) a Couple of Friends Are Hanging Outside for a Picnic. They Keep Roaming in the Road on A

Case Closed (Surrealistic Horror Story) A couple of friends are hanging outside for a picnic. They keep roaming in the road on a shinny day. They come to find a haunted house and decided to explore it. The house is filled with dust and dirt is almost about to break up. Nevertheless they decided to go in and take a break before proceeding ahead. After exploring the house, friends get hungry and sit down in a room to have lunch. They realized they are out of food and decided to bring some foods while one girl stayed inside as she was getting headache and takes a nap while others go out. She sleeps for many hours (time lapse) and wakes up at night. She noticed no one around in the haunted house and starts to panic and decide to open every door looking for others but ended up going to the same place all the time. Then she tries to take a call for her friends with her smart phone but realize there are no signals in the smart phone. Then she hears an old cartoon laughing sound somewhere in the house and follows that room. She pokes in and shocks seeing a little girl watching a black and white TV. The place implies 70‟s year old vintage environment. The TV, clothes the little girl is wearing, foods all of them were object of 70 year. She gets closer and tries to touch her but realize the girl is unaware of her presence and could not feel as she continues watching the cartoon while laughing miserably. -

Chapter 4 Pre-Trial Criminal Procedure

CHAPTER 4 PRE-TRIAL CRIMINAL PROCEDURE I. INTRODUCTION Japan is a unitary state, and the same criminal procedure applies throughout the nation. The Code of Criminal Procedure of 1948 (hereinafter CCP), the Act on Criminal Trials Examined under the Lay Judge System, and the Rules of Criminal Procedure of 1949 are the principal sources of law. II. CONSTITUTIONAL SAFEGUARDS The Constitution of Japan has an extensive list of constitutional guarantees that relate to the criminal process. Article 31 provides that “no person shall be deprived of life, or liberty, nor shall any other criminal penalty be imposed, except according to procedure established by law,” while Article 33 states that “no person shall be apprehended except upon warrant issued by a competent judicial officer which specifies the offence with which the person is charged, unless he is apprehended, the offence being committed.” Further, as prescribed in Article 34, “no person shall be arrested or detained without being at once informed of the charges against him or without the immediate privilege of counsel; nor shall he be detained without adequate cause; and upon demand of any person such cause must be immediately shown in open court in his presence and the presence of his counsel.” Article 35 provides for the protection of one’s residence and property, stating “the right of all persons to be secure in their homes, papers and effects against entries, searches and seizures shall not be impaired except upon warrant issued for adequate cause and particularly describing the place