SEILA LAW LLC V. CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Words That Work: It's Not What You Say, It's What People Hear

ï . •,";,£ CASL M T. ^oÛNTAE À SUL'S, REVITA 1ENT, HASSLE- NT_ MAIN STR " \CCOUNTA ;, INNOVAT MLUE, CASL : REVITA JOVATh IE, CASL )UNTAE CO M M XIMEN1 VlTA • Ml ^re aW c^Pti ( °rds *cc Po 0 ^rof°>lish lu*t* >nk Lan <^l^ gua a ul Vic r ntz °ko Ono." - Somehow, W( c< Words are enorm i Jheer pleasure of CJ ftj* * - ! love laag^ liant about Words." gM °rder- Franl< Luntz * bril- 'Frank Luntz understands the power of words to move public Opinion and communicate big ideas. Any Democrat who writes off his analysis and decades of experience just because he works for the other side is making a big mistake. His les sons don't have a party label. The only question is, where s our Frank Luntz^^^^^^^™ îy are some people so much better than others at talking their way into a job or nit of trouble? What makes some advertising jingles cut through the clutter of our crowded memories? What's behind winning campaign slogans and career-ending political blunders? Why do some speeches resonate and endure while others are forgotten moments after they are given? The answers lie in the way words are used to influence and motivate, the way they connect thought and emotion. And no person knows more about the intersection of words and deeds than language architect and public-opinion guru Dr. Frank Luntz. In Words That Work, Dr. Luntz not only raises the curtain on the craft of effective language, but also offers priceless insight on how to find and use the right words to get what you want out of life. -

Appendix File Anes 1988‐1992 Merged Senate File

Version 03 Codebook ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE ANES 1988‐1992 MERGED SENATE FILE USER NOTE: Much of his file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As a result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. MASTER CODES: The following master codes follow in this order: PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE CAMPAIGN ISSUES MASTER CODES CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP CODE ELECTIVE OFFICE CODE RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE MASTER CODE SENATOR NAMES CODES CAMPAIGN MANAGERS AND POLLSTERS CAMPAIGN CONTENT CODES HOUSE CANDIDATES CANDIDATE CODES >> VII. MASTER CODES ‐ Survey Variables >> VII.A. Party/Candidate ('Likes/Dislikes') ? PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PEOPLE WITHIN PARTY 0001 Johnson 0002 Kennedy, John; JFK 0003 Kennedy, Robert; RFK 0004 Kennedy, Edward; "Ted" 0005 Kennedy, NA which 0006 Truman 0007 Roosevelt; "FDR" 0008 McGovern 0009 Carter 0010 Mondale 0011 McCarthy, Eugene 0012 Humphrey 0013 Muskie 0014 Dukakis, Michael 0015 Wallace 0016 Jackson, Jesse 0017 Clinton, Bill 0031 Eisenhower; Ike 0032 Nixon 0034 Rockefeller 0035 Reagan 0036 Ford 0037 Bush 0038 Connally 0039 Kissinger 0040 McCarthy, Joseph 0041 Buchanan, Pat 0051 Other national party figures (Senators, Congressman, etc.) 0052 Local party figures (city, state, etc.) 0053 Good/Young/Experienced leaders; like whole ticket 0054 Bad/Old/Inexperienced leaders; dislike whole ticket 0055 Reference to vice‐presidential candidate ? Make 0097 Other people within party reasons Card PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PARTY CHARACTERISTICS 0101 Traditional Democratic voter: always been a Democrat; just a Democrat; never been a Republican; just couldn't vote Republican 0102 Traditional Republican voter: always been a Republican; just a Republican; never been a Democrat; just couldn't vote Democratic 0111 Positive, personal, affective terms applied to party‐‐good/nice people; patriotic; etc. -

6Upreme Court of ®Bio

1" tC,e 6upreme Court of ®bio IN RE: DARIAN J. SMITH, Case No. 2008-1624 A Delinquent Child. On Appeal from the Allen County Court of Appeals, Third Appellate District Court of Appeals Case No. 1-07-58 AMICUS CURIAE OHIO ATTORNEY GENERAL RICHARD CORDRAY'S NOTICE OF APPEARANCE OF ADDITIONAL COUNSEL BROOKE M. BURNS* (0080256) RICHARD CORDRAY (0038034) *Counsel ofRecord Attorney General of Ohio Assistant State Public Defender 250 E. Broad St., Suite 1400 BENJAMIN C. MIZER* (0083089) Columbus, Ohio 43215 Solicitor General 614-466-5394 *Counsel ofRecord 614-752-5167 fax ALEXANDRA T. SCHIMMER (0075732) brooke.burns@opd. ohio. gov Chief Deputy Solicitor General DAVID M. LIEBERMAN (pro hac vice) Counsel for Appellant Smith Deputy Solicitor CHRISTOPHER P. CONOMY (0072094) JUERGEN A. WALDICK (0030399) JAMES A. HOGAN (0071064) Allen County Prosecutor Assistant Attorneys General CHRISTINA L. STEFFAN* (0075206) 30 East Broad Street, 17th Floor Assistant Prosecutor Columbus, Ohio 43215 *Counsel ofRecord 614-466-8980 204 N. Main St., Suite 302 614-466-5087 fax Lima, Ohio 45801 benj amin.mizer@ohioattorneygeneral. gov 419-228-3700 419-222-2462 fax Counsel for Amicus Curiae [email protected] Ohio Attorney General Richard Cordray Counsel for Appellee State of Ohio ME OC'1' C Z ?009 CLERK OF COURT SUpREME COURT OF OHIO AMICUS CURIAE OHIO ATTORNEY GENERAL RICHARD CORDRAY'S NOTICE OF APPEARANCE OF ADDITIONAL COUNSEL Assistant Attorney General James A. Hogan enters his appearance as co-counsel for Amicus Curiae Ohio Attorney General Richard Cordray in the above captioned matter. Benjamin C. Mizer will remain as Counsel of Record in the case. -

Fake News Detection in Social Media

Fake news detection in social media Kasseropoulos Dimitrios-Panagiotis SID: 3308190011 SCHOOL OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Science (MSc) in Data Science JANUARY, 2021 THESSALONIKI - GREECE i Fake news detection in social media Kasseropoulos Dimitrios-Panagiotis SID: 3308190011 Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Christos Tjortjis Supervising Committee Members: Prof. Panagiotis Bozanis Dr. Leonidas Akritidis SCHOOL OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Science (MSc) in Data Science JANUARY, 2021 THESSALONIKI - GREECE ii Abstract This dissertation was written as a part of the MSc in Data Science at the International Hellenic University. The easy propagation and access to information in the web has the potential to become a serious issue when it comes to disinformation. The term “fake news” is describing the intentional propagation of fake news with the intent to mislead and harm the public, and has gained more attention since the U.S elections of 2016. Recent studies have used machine learning techniques to tackle it. This thesis reviews the style-based machine learning approach which relies on the textual information of news, such as the manually extraction of lexical features from the text (e.g. part of speech counts), and testing the performance of both classic and non-classic (artificial neural networks) algorithms. We have managed to find a subset of best performing linguistic features, using information-based metrics, which also tend to agree with the already existing literature. Also, we combined the Name Entity Recognition (NER) functionality of spacy’s library with the FP Growth algorithm to gain a deeper perspective of the name entities used in the two classes. -

Teen Stabbing Questions Still Unanswered What Motivated 14-Year-Old Boy to Attack Family?

Save $86.25 with coupons in today’s paper Penn State holds The Kirby at 30 off late Honoring the Center’s charge rich history and its to beat Temple impact on the region SPORTS • 1C SPECIAL SECTION Sunday, September 18, 2016 BREAKING NEWS AT TIMESLEADER.COM '365/=[+<</M /88=C6@+83+sǍL Teen stabbing questions still unanswered What motivated 14-year-old boy to attack family? By Bill O’Boyle Sinoracki in the chest, causing Sinoracki’s wife, Bobbi Jo, 36, ,9,9C6/Ľ>37/=6/+./<L-97 his death. and the couple’s 17-year-old Investigators say Hocken- daughter. KINGSTON TWP. — Specu- berry, 14, of 145 S. Lehigh A preliminary hearing lation has been rampant since St. — located adjacent to the for Hockenberry, originally last Sunday when a 14-year-old Sinoracki home — entered 7 scheduled for Sept. 22, has boy entered his neighbors’ Orchard St. and stabbed three been continued at the request house in the middle of the day members of the Sinoracki fam- of his attorney, Frank Nocito. and stabbed three people, kill- According to the office of ing one. ily. Hockenberry is charged Magisterial District Justice Everyone connected to the James Tupper and Kingston case and the general public with homicide, aggravated assault, simple assault, reck- Township Police Chief Michael have been wondering what Moravec, the hearing will be lessly endangering another Photo courtesy of GoFundMe could have motivated the held at 9:30 a.m. Nov. 7 at person and burglary in connec- In this photo taken from the GoFundMe account page set up for the Sinoracki accused, Zachary Hocken- Tupper’s office, 11 Carverton family, David Sinoracki is shown with his wife, Bobbi Jo, and their three children, berry, to walk into a home on tion with the death of David Megan 17; Madison, 14; and David Jr., 11. -

Between the Courts and Congress Is the Future of the CFPB in Jeopardy?

Between the Courts and Congress Is the Future of the CFPB in Jeopardy? Throughout the nearly six years of its existence, the The underlying dispute first arose in 2015, which resulted in a CFPB administrative law judge’s recommendation of a US$6.5 Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB or the million fine against PHH for allegedly requiring unlawful kickbacks from mortgage insurers in violation of Section 8 of the Real Estate “Bureau”) has been the target of attacks in various Settlement Procedures Act (RESPA). PHH appealed that decision to courtrooms and the halls of Congress. No doubt the CFPB Director Richard Cordray, who rejected its arguments and then increased the fine to US$109 million. previous administration and the then Democrat- On October 11, 2016, the DC Circuit vacated the US$109 million controlled Congress designed the CFPB to withstand enforcement order by the CFPB, finding that not only was its interpretation of RESPA unreasonable, but that the CFPB’s structure political winds (i.e., an independent agency not is too unaccountable to be constitutional and poses an opportunity subject to congressional appropriations and headed for the Director to abuse his power. To remedy this potential for abuse of power, the Court ordered that the CFPB would no longer by a single director appointed by the President, be an “independent” agency, but “now will operate as an executive removable only for cause). agency” and that President Trump “now has the power to supervise and direct the Director of the CFPB, and may remove the Director at At this point, however, President Trump, the Republican-controlled will at any time.” This decision has been stayed pending the results House and Senate and the courts are about to test its durability. -

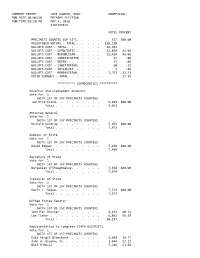

Summary Report Lake County, Ohio Unofficial Run Date:05/04/10 Primary Election Run Time:10:20 Pm May 4, 2010 Statistics

SUMMARY REPORT LAKE COUNTY, OHIO UNOFFICIAL RUN DATE:05/04/10 PRIMARY ELECTION RUN TIME:10:20 PM MAY 4, 2010 STATISTICS VOTES PERCENT PRECINCTS COUNTED (OF 157). 157 100.00 REGISTERED VOTERS - TOTAL . 156,210 BALLOTS CAST - TOTAL. 26,952 BALLOTS CAST - DEMOCRATIC . 11,058 41.03 BALLOTS CAST - REPUBLICAN . 12,414 46.06 BALLOTS CAST - CONSTITUTION . 17 .06 BALLOTS CAST - GREEN. 23 .09 BALLOTS CAST - LIBERTARIAN. 60 .22 BALLOTS CAST - SOCIALIST . 7 .03 BALLOTS CAST - NONPARTISAN. 3,373 12.51 VOTER TURNOUT - TOTAL . 17.25 ********** (DEMOCRATIC) ********** Governor and Lieutenant Governor Vote for 1 (WITH 157 OF 157 PRECINCTS COUNTED) Ted Strickland. 9,021 100.00 Total . 9,021 Attorney General Vote for 1 (WITH 157 OF 157 PRECINCTS COUNTED) Richard Cordray . 7,973 100.00 Total . 7,973 Auditor of State Vote for 1 (WITH 157 OF 157 PRECINCTS COUNTED) David Pepper . 7,430 100.00 Total . 7,430 Secretary of State Vote for 1 (WITH 157 OF 157 PRECINCTS COUNTED) Maryellen O'Shaughnessy. 7,874 100.00 Total . 7,874 Treasurer of State Vote for 1 (WITH 157 OF 157 PRECINCTS COUNTED) Kevin L. Boyce. 7,572 100.00 Total . 7,572 United States Senator Vote for 1 (WITH 157 OF 157 PRECINCTS COUNTED) Jennifer Brunner . 4,135 40.71 Lee Fisher . 6,022 59.29 Total . 10,157 Representative to Congress (14TH DISTRICT) Vote for 1 (WITH 157 OF 157 PRECINCTS COUNTED) Dale Virgil Blanchard . 1,658 19.77 John H. Greene, Jr. 1,444 17.22 Bill O'Neill . 5,286 63.02 Total . 8,388 Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Vote for 1 (WITH 157 OF 157 PRECINCTS COUNTED) Eric Brown . -

Access to Justice for Children: Mexico

ACCESS TO JUSTICE FOR CHILDREN: MEXICO This report was produced by White & Case LLP in November 2013 but may have been subsequently edited by Child Rights International Network (CRIN). CRIN takes full responsibility for any errors or inaccuracies in the report. I. What is the legal status of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC)? A. What is the status of the CRC and other relevant ratified international instruments in the national legal system? The CRC was signed by Mexico on 26 January 1990, ratified on 21 November 1990, and published in the Federal Official Gazette (Diario Oficial de la Federación) on 25 January 1991. In addition to the CRC, Mexico has ratified the Optional Protocols relating to the involvement of children in armed conflict and the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography. All treaties signed by the President of Mexico, with the approval of the Senate, are deemed to constitute the supreme law of Mexico, together with the Constitution and the laws of the Congress of the Union.1 The CRC is therefore part of national law and may serve as a legal basis in any proceedings before the national courts. It is also part of the supreme law of Mexico as a whole and must be implemented at federal level and in all the individual states.2 B. Does the CRC take precedence over national law The CRC has been interpreted to take precedence over national laws, but not the Constitution. According to doctrinal thesis LXXVII/99 of November 1999, international treaties are ranked second immediately after the Constitution and ahead of federal and local laws.3 On several occasions, Mexico’s Supreme Court has stated that international treaties take precedence over national law, mainly in the case of human rights.4 C. -

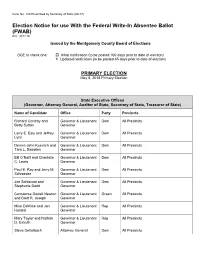

Election Notice for Use with the Federal Write-In Absentee Ballot (FWAB) R.C

Form No. 120 Prescribed by Secretary of State (09-17) Election Notice for use With the Federal Write-In Absentee Ballot (FWAB) R.C. 3511.16 Issued by the Montgomery County Board of Elections BOE to check one: Initial notification (to be posted 100 days prior to date of election) X Updated notification (to be posted 45 days prior to date of election) PRIMARY ELECTION May 8, 2018 Primary Election State Executive Offices (Governor, Attorney General, Auditor of State, Secretary of State, Treasurer of State) Name of Candidate Office Party Precincts Richard Cordray and Governor & Lieutenant Dem All Precincts Betty Sutton Governor Larry E. Ealy and Jeffrey Governor & Lieutenant Dem All Precincts Lynn Governor Dennis John Kucinich and Governor & Lieutenant Dem All Precincts Tara L. Samples Governor Bill O’Neill and Chantelle Governor & Lieutenant Dem All Precincts C. Lewis Governor Paul E. Ray and Jerry M. Governor & Lieutenant Dem All Precincts Schroeder Governor Joe Schiavoni and Governor & Lieutenant Dem All Precincts Stephanie Dodd Governor Constance Gadell-Newton Governor & Lieutenant Green All Precincts and Brett R. Joseph Governor Mike DeWine and Jon Governor & Lieutenant Rep All Precincts Husted Governor Mary Taylor and Nathan Governor & Lieutenant Rep All Precincts D. Estruth Governor Steve Dettelbach Attorney General Dem All Precincts Dave Yost Attorney General Rep All Precincts Zack Space Auditor of State Dem All Precincts Keith Faber Auditor of State Rep All Precincts Kathleen Clyde Secretary of State Dem All Precincts Frank LaRose Secretary of State Rep All Precincts Rob Richardson Treasurer of State Dem All Precincts Sandra O’Brien Treasurer of State Rep All Precincts Robert Sprague Treasurer of State Rep All Precincts Paul Curry (Write-In) Treasurer of State Green All Precincts U.S. -

Combatting White Nationalism: Lessons from Marx by Andrew Kliman

Combatting White Nationalism: Lessons from Marx by Andrew Kliman October 2, 2017 version Abstract This essay seeks to draw lessons from Karl Marx’s writings and practice that can help combat Trumpism and other expressions of white nationalism. The foremost lesson is that fighting white nationalism in the tradition of Marx entails the perspective of solidarizing with the “white working class” by decisively defeating Trumpism and other far-right forces. Their defeat will help liberate the “white working class” from the grip of reaction and thereby spur the independent emancipatory self-development of working people as a whole. The anti-neoliberal “left” claims that Trump’s electoral victory was due to an uprising of the “white working class” against a rapacious neoliberalism that has caused its income to stagnate for decades. However, working-class income (measured reasonably) did not stagnate, nor is “economic distress” a source of Trump’s surprisingly strong support from “working-class” whites. And by looking back at the presidential campaigns of George Wallace between 1964 and 1972, it becomes clear that Trumpism is a manifestation of a long-standing white nationalist strain in US politics, not a response to neoliberalism or globalization. Marx differed from the anti-neoliberal “left” in that he sought to encourage the “independent movement of the workers” toward human emancipation, not further the political interests of “the left.” Their different responses to white nationalism are rooted in this general difference. Detailed analysis of Marx’s writings and activity around the US Civil War and the Irish independence struggle against England reveals that Marx stood for the defeat of the Confederacy, and the defeat of England, largely because he anticipated that these defeats would stimulate the independent emancipatory self-development of the working class. -

Online Media and the 2016 US Presidential Election

Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Faris, Robert M., Hal Roberts, Bruce Etling, Nikki Bourassa, Ethan Zuckerman, and Yochai Benkler. 2017. Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election. Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society Research Paper. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33759251 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA AUGUST 2017 PARTISANSHIP, Robert Faris Hal Roberts PROPAGANDA, & Bruce Etling Nikki Bourassa DISINFORMATION Ethan Zuckerman Yochai Benkler Online Media & the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This paper is the result of months of effort and has only come to be as a result of the generous input of many people from the Berkman Klein Center and beyond. Jonas Kaiser and Paola Villarreal expanded our thinking around methods and interpretation. Brendan Roach provided excellent research assistance. Rebekah Heacock Jones helped get this research off the ground, and Justin Clark helped bring it home. We are grateful to Gretchen Weber, David Talbot, and Daniel Dennis Jones for their assistance in the production and publication of this study. This paper has also benefited from contributions of many outside the Berkman Klein community. The entire Media Cloud team at the Center for Civic Media at MIT’s Media Lab has been essential to this research. -

Putin's New Russia

PUTIN’S NEW RUSSIA Edited by Jon Hellevig and Alexandre Latsa With an Introduction by Peter Lavelle Contributors: Patrick Armstrong, Mark Chapman, Aleksandr Grishin, Jon Hellevig, Anatoly Karlin, Eric Kraus, Alexandre Latsa, Nils van der Vegte, Craig James Willy Publisher: Kontinent USA September, 2012 First edition published 2012 First edition published 2012 Copyright to Jon Hellevig and Alexander Latsa Publisher: Kontinent USA 1800 Connecticut Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20009 [email protected] www.us-russia.org/kontinent Cover by Alexandra Mozilova on motive of painting by Ilya Komov Printed at Printing house "Citius" ISBN 978-0-9883137-0-5 This is a book authored by independent minded Western observers who have real experience of how Russia has developed after the failed perestroika since Putin first became president in 2000. Common sense warning: The book you are about to read is dangerous. If you are from the English language media sphere, virtually everything you may think you know about contemporary Rus- sia; its political system, leaders, economy, population, so-called opposition, foreign policy and much more is either seriously flawed or just plain wrong. This has not happened by accident. This book explains why. This book is also about gross double standards, hypocrisy, and venal stupidity with western media playing the role of willing accomplice. After reading this interesting tome, you might reconsider everything you “learn” from mainstream media about Russia and the world. Contents PETER LAVELLE ............................................................................................1