A Geochemist in His Garden of Eden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teen Stabbing Questions Still Unanswered What Motivated 14-Year-Old Boy to Attack Family?

Save $86.25 with coupons in today’s paper Penn State holds The Kirby at 30 off late Honoring the Center’s charge rich history and its to beat Temple impact on the region SPORTS • 1C SPECIAL SECTION Sunday, September 18, 2016 BREAKING NEWS AT TIMESLEADER.COM '365/=[+<</M /88=C6@+83+sǍL Teen stabbing questions still unanswered What motivated 14-year-old boy to attack family? By Bill O’Boyle Sinoracki in the chest, causing Sinoracki’s wife, Bobbi Jo, 36, ,9,9C6/Ľ>37/=6/+./<L-97 his death. and the couple’s 17-year-old Investigators say Hocken- daughter. KINGSTON TWP. — Specu- berry, 14, of 145 S. Lehigh A preliminary hearing lation has been rampant since St. — located adjacent to the for Hockenberry, originally last Sunday when a 14-year-old Sinoracki home — entered 7 scheduled for Sept. 22, has boy entered his neighbors’ Orchard St. and stabbed three been continued at the request house in the middle of the day members of the Sinoracki fam- of his attorney, Frank Nocito. and stabbed three people, kill- According to the office of ing one. ily. Hockenberry is charged Magisterial District Justice Everyone connected to the James Tupper and Kingston case and the general public with homicide, aggravated assault, simple assault, reck- Township Police Chief Michael have been wondering what Moravec, the hearing will be lessly endangering another Photo courtesy of GoFundMe could have motivated the held at 9:30 a.m. Nov. 7 at person and burglary in connec- In this photo taken from the GoFundMe account page set up for the Sinoracki accused, Zachary Hocken- Tupper’s office, 11 Carverton family, David Sinoracki is shown with his wife, Bobbi Jo, and their three children, berry, to walk into a home on tion with the death of David Megan 17; Madison, 14; and David Jr., 11. -

Program 2018 Barevně

Pátek Hlavní sál Sci-fi a fantasy Britcom plus Doctor Who Herna 19:00 Zahájení linie + DW kvíz * * * Volné hraní Préza & Gomi Promítání Britcom na p ř ání 20:00 Slavnostní zahájení Alexis Barbucha & Viky The Five(ish) Doctors Reboot / The Curse of Fatal Death / Volné hraní RD: Nachystejte kv ětiná če The Web of Caves 21:00 2000 let stará sci-fi? Vládce jak ho (ne)znáte Geek šperky č ěč Kamil Gregor, Petr Gongala Všechno erné je k n emu dobré Dani-El Daphné Historie Disney Hannibal Jiná dimenze aneb v ědecké teorie Allie Královský bál 22:00 Rok v život ě Johna Barrowmana multiversa (prezentace a hraní) Ziina Vít ězslav Škorpík Kolaps Fawlty Towers: Re-Opened 23:00 RD: Bodysnatcher Lucifer Šipky na kozatou rosni č ku Tezi Mark of Rani * * * Lucy Leveller Herna tým Sobota Hlavní sál Sci-fi a fantasy Britcom plus Doctor Who Herna 9:00 Jak se dabuje Červený trpaslík Apokalypsa a postapo p ř ežívání Kreslení Pythoni Vyrob si svého pana Filutu The End of the World Marty, Jessica & Áda Sherly?! Le fille Ash Tezi 10:00 10 britských seriál ů, Filmové narážky na Doctora Who Č apkový workshop které stojí za to vid ět Doktor Lucerna 11:00 Mistrovství ČR v zírání Č lenská sch ů ze KTP LadyAlex Kohy, Viky, Obscuro Hadati, VeHaLi, Dalila Doctor Who and The Mind of 12:00 Sweeney Todd - cesta legendy Malý rybá ř Nonsense Aludneva Herna tým Scott Lee Hansen 13:00 RD: S12E01 Cured Garth Marenghi´s Darkplace Doktor vál č í Poznej film podle hlášky ě č RD: S12E02 Siliconia Kyberpunkokvý d de ku, Yenn Fritzi DORFL the Sane ě vypráv j… Monty Pythonovy švihlé 14:00 Zdá se, že mám v bidetu žábu Pro č mít rád cynické svin ě Druhý doktor a jeho p ř íb ě hy Ji ří W. -

Significant Achievements in the Planetary Geology Program 1977-1978

NASA Contractor Report 3077 Significant Achievements in the Planetary Geology Program 1977-1978 DECEMBER 1978 NASA NASA Contractor Report 3077 Significant Achievements in the Planetary Geology Program 1977-1978 Prepared for NASA Office of Space Science NASA National Aeronautics and Space Administration Scientific and Technical Information Office 1978 James W. Head Editor Brown University Contributing Authors Fraser Fanale Elbert King Jet Propulsion Laboratory University of Houston Clark Chapman Paul Komar Planetary Science Institute Oregon State University Sean Solomon Gerald Schaber Massachusetts Institute of Technology U. S. Geological Survey Hugh Kieffer Roger Smith University of California-Los Angeles University of Houston James Stephens Mike Mai in Jet Propulsion Laboratory Jet Propulsion Laboratory Ray Batson Alex Woronow U. S. Geological Survey University of Arizona ii Table of Contents Introduction v Constraints on Solar System Formation 1 Asteroids, Comets, and Satellites 5 Constraints on Planetary Interiors 13 Volatiles and Regolith 16 Instrument Development Techniques 21 Planetary Cartography 23 Geological and Geochemical Constraints on Planetary Evolution 24 Fluvial Processes and Channel Formation 28 Volcanic Processes 35 Eolian Processes 38 Radar Studies of Planetary Surfaces 44 Cratering as a Process, Landform, and Dating Method 46 Workshop on the Tharsis Region of Mars 49 Planetary Geology Field Conference on Eolian Processes 52 Report of the Crater Analysis Techniques Working Group 53 111 Introduction The 9th annual meeting of the Planetary Geology Program Principal Investigators was held May 31 - June 2, 1978 in Tucson, Arizona at the University of Arizona. The papers presented there represented the high points of research carried out in the Planetary Geology Program of NASA's Office of Space Science, Division of Planetary Programs. -

Annual Meeting & Exposition Annual

Vol. 9, No. 6 June 1999 GSA TODAY A Publication of the Geological Society of America 1999 Annual Meeting & Exposition Colorado ConvenConventiontion CenterCenter HyattHyatt RegencyRegency HotelHotel MarriottMarriott CityCity CenterCenter HotelHotel OctoberOctober 25–28,25–28, 19991999 Denver,Denver, ColoradoColorado Table of Contents Crossing Divides Abstracts with Programs . 32 Convenience Information . 26 Employment Service . 22 World Wide Web Exhibits . 20 Visit the GSA Web site to obtain more details and to get the latest information on the Annual Meeting. Field Trips . 13 www.geosociety.org Graduate School Information Forum . 23 Guest Activities . 24 Deadlines Hot Topics at Noon . 9 Abstracts due July 12 Housing . 28 Preregistration and Housing due September 17 (forms(forms enclosed)enclosed) How to Submit Your Abstract . 12 Institute for Earth Science and the Environment . 22 For More Information Call: (303) 447-2020 or 1-800-472-1988 International Program . 6 Call: (303) 447-2020 or 1-800-472-1988 Fax: 303-447-0648 K–16 Education Program . 18 E-mail: [email protected] Membership . 30 Web: www.geosociety.org Registration . 30 Short Courses . 16 Cover photos by John A. Karachewski: Large photo shows the Special Events . 23 Continental Divide—Sawatch Range, Collegiate Peaks Wilderness, Special Programs . 22 Colorado; small photo taken near James Peak, Colorado Technical Program . 3 Travel . 25 Crossing Divides Annual Meeting Committee General Co-Chairs: Mary Kraus, David Budd, University of Colorado Technical Program Co-Chairs: -

The Implications of Lake History for Conservation Biology

THE IMPLICATIONS OF LAKE HISTORY FOR CONSERVATION BIOLOGY Kristine Alexia Ciruna A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Zoology, University of Toronto O Copyright by Kristine Alexia Cinina 1999 National Libraiy Biiiotheque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services sewices bibliographiques 395 Wellmgtori Street 395, nie WeJMngton OüawaON K1A ON4 OitawaON K1AW Canada CaMda The author has gmnted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or selî reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur fomiat électronique. The author retains ownershp of the L'auteur consme la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the &oit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Abstract ABSTRACT Ciruna, Kristine Alexia. 1999. The implications of lake history for conservation biology. Ph.D. dissertation. Department of Zoology, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario. The historical formation of aquatic ecosystems and the regional environmental processes acting at the watershed level are important components in the conservation of aquatic ecosystems which are often'neglected. This thesis integrates the fields of cornmunity and landscape ecology. -

River Depletion Due to Pumping of a Well Near a River Glover

River Depletion due to Pumping of a Well Near a River Glover OFFICERS OF THE UNION, 1953-58 SECTIONS OF THE UNION JOHN A. FLEMING, Honorary President Section of Geodesy JAMES B. MACELWANE, President ALBERT J HosKiNsoN, President MAURICE EWING, Vice President AMERICAN GEOPHYSICAL UNION Section of Seismology Ross JOHN PUTNAM MARBLE, General Secretary R. HEINRICH, President Section of Meteorology WALDO E. SMITH. Executive Secretary EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE PHIL E. CHURCH, President 1530 P Street, N. W. Section of Terrestrial Magnetism Washington 5, D. C. and Electricity VICTOR EX-OFFICIO MEMBERS American National Committee VACQUIER, President of the Section of Oceanography CHAIRMAN, NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics RIciimu) H. FLEMING, President CHAIRMEN, DIVISIONS OF THE and Committee on Geophysics of the Section of Volcanology NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL Wii.i.awm F. Fostiwo, President International Relations NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL Section of Hydrology Physical Sciences HAROLD G. Wrud, President Chemistry and Chemical Technology WASHINGTON, D. C. Geology Section of Tectonophysics and Geography FRANCIS BIRCH, President Biology and Agriculture AMERICAN OFFICERS International Union of Geodesy and 1530 P Street, N.W. Geophysics Washington 5, D. C. October 22, 1954 Messrs. liobert E. Glover & Glenn G. Balmer, Bureau of Reclamation Bldg. 53, Denver Federal Center Denver 2, Colorado Gentlemen: Thank you for your letter of October 13 with which you forwarded the closing discussion on your paper relating to river depletion. We are for- warding this, together with Hantush's discussion of your paper, to the Editor and in due course will write to you further. We are calling the Editor's attention to the closing paragraptf your letter. -

Columbia University Task Force on Climate: Report

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY TASK FORCE ON CLIMATE: REPORT Delivered to President Bollinger December 1, 2019 UNIVERSITY TASK FORCE ON CLIMATE FALL 2019 Contents Preface—University Task Force Process of Engagement ....................................................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary: Principles of a Climate School .............................................................................................................................. 4 Introduction: The Climate Challenge ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 The Columbia University Response ....................................................................................................................................................... 7 Columbia’s Strengths ........................................................................................................................................................................ 7 Columbia’s Limitations ...................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Why a School? ................................................................................................................................................................................... 9 A Columbia Climate School ................................................................................................................................................................. -

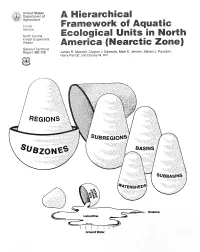

Aquatic Ecomap Team to Develop the Framework, Process Comments, and Develop a Plan Forrevision.These Scientistsare

_i__¸_._. V_!_i Depa_"tment of e_a IC_ .-,4_:..._.A_..:,_,,_gricu 1t u_'e ServiceFo os Framewerku of Aquatim c North Centrai EC@J@g_CaJ U_itS _ N@_th Forest Experiment s [] Station A_er_ca {Nearct_c Z@_e_ General Technical Report NC-17'6 James R. Maxwell, Clayton J. Edwards, Mark E. Jensen, Steven J. Paustian, Harry Parrott, and Donley M. Hitl 8 • _ ...... "'::'":' i:. "S" " : ":','1 _ . / REG I0 NS':_; '"::;:s_:::."_--. .---..:-:!.!:::!:.::_:. ..... •. :.,.:,: .,. -,::.:, .......,.-,.-4S:ifi -.- i::ti/;:.:_: """.::""-:.: .... "':::.:.';.i" . :':" "':":": -. -._ . •....:...{: • . ...:" ZON • .- "." . .. • " . "'...:.:. • .....:....:....:_..-:..:):. -.-. ..... ,:.':::'.':: . .., .... '"_::.--..:.:i i ''_{:;ti}{i_:/.... sub " ,Lri_;gi, • Riverine GroundWater II II _ II I III II I II ],.r ', _ _r',_-- ACFA_OV_rLEDGI_NTS The authors wish to thank the many scientistswho commented on the draftsof thispaper during itspreparation. Their comments dramatically improved the qualiW of the product. These scientistsare listedin Appen- dix F. Specialthanks are offeredto 10 of these scientists,who met with the Aquatic Ecomap team to develop the framework, process comments, and develop a plan forrevision.These scientistsare: Patrick Bourgeron, The Nature Conservancy, Boulder, CO (geoclimatic) James Deacon, Universityof Nevada, Las Vegas, NV (zoogeography) Iris Goodman, Environmental Protection Agency, Las Vegas, NV (ground water) Gordon Grant, Forest Service, Corvallis, OR [riverine) Richard Lillie, Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Winona, WI (lacustrine) W.L. Minckley, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ (zoogeography) Kerry Overton, Forest Service, Boise, [D (riverine) Nick Schmal, Forest Service, Laramie, WY (riverine, lacustrine) Steven Walsh, Fish and Wildlife Service, Gainesville, FL (zoogeography) Mike Wireman, Environmental Protection Agency, Denver, CO (ground water) We wish to especially acknowledge the contributions of Mike Wireman and Iris Goodman of the Environmental Protection Agency. -

Recommendations and Guidelines, the Incorporation of Results of Current Crustal Evolution Studies Into K-12 Curricula

DOCUMENT RESUME 1D 104 664 SE 018 772 AUTHOR Stoever, Edward C., Jr. TITLE Recommendations and Guidelines, The Incorporation of Results of Current Crustal Evolution Studies into K-12 Curricula. A Report of the National Association of Geology Teachers Conference on K-12 Crustal Evolution EducatioL (Western Hilli State-Lodge, Oklahoma, September 16-18, 1974) . INSTITUTION National Association of Geology Teachers. SPONS AGENCY National Science Poundation, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE Jan 75 NOTE 53p. EDRS PRICE NF -$0.76 HC-$3.32 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Conference Reports; *Curriculum Development; Curriculum Guides; *Earth Science; Elementary Education; Elementary Secondary Education; Geology; *Science Education; Secondary Education; Teaching Guides ABSTRACT The National Association of Geology Teachers (NAGT) .conducted an assessment of -the impliCations of current-studies encompassing the theories of continental drift, polar wandering, sea-floor spreading, and plate tectonics to K-12 education, and presented in this document recommendation's for the incorporation of these concepts into school curricula. A detailed description of tie. current status of crustal evolution " studies is presented. Conclusions drawn at the conference indicate the desirability of incorporation of -these topics, as well as the feasibility of the incorporation. Recommendations show grades six through ten as primary targets. An organizational scheme is presented, as are charts shoving how new information, ideas, and materials would be processed for classroom use. Suggestions for preparatibn of curriculum materials and introductory teacher materials are suggested.- The appendices include a list of conference participants, a pre-conference report,an exaiple of-a lesson activity, suggested lesson activity topics, and suggested teacher resource book contents. -

Download New Glass Review 15

eview 15 The Corning Museum of Glass NewGlass Review 15 The Corning Museum of Glass Corning, New York 1994 Objects reproduced in this annual review Objekte, die in dieser jahrlich erscheinenden were chosen with the understanding Zeitschrift veroffentlicht werden, wurden unter that they were designed and made within der Voraussetzung ausgewahlt, daB sie inner- the 1993 calendar year. halb des Kalenderjahres 1993 entworfen und gefertigt wurden. For additional copies of New Glass Review, Zusatzliche Exemplare der New Glass Review please contact: konnen angefordert werden bei: The Corning Museum of Glass Sales Department One Museum Way Corning, New York 14830-2253 Telephone: (607) 937-5371 Fax: (607) 937-3352 All rights reserved, 1994 Alle Rechte vorbehalten, 1994 The Corning Museum of Glass The Corning Museum of Glass Corning, New York 14830-2253 Corning, New York 14830-2253 Printed in Frechen, Germany Gedruckt in Frechen, Bundesrepublik Deutschland Standard Book Number 0-87290-133-5 ISSN: 0275-469X Library of Congress Catalog Card Number Aufgefuhrt im Katalog der Library of Congress 81-641214 unter der Nummer 81 -641214 Table of Contents/lnhalt Page/Seite Jury Statements/Statements der Jury 4 Artists and Objects/Kunstlerlnnen und Objekte 10 Bibliography/Bibliographie 30 A Selective Index of Proper Names and Places/ Ausgewahltes Register von Eigennamen und Orten 58 etztes Jahr an dieser Stelle beklagte ich, daB sehr viele Glaskunst- Jury Statements Ller aufgehort haben, uns Dias zu schicken - odervon vorneherein nie Zeit gefunden haben, welche zu schicken. Ich erklarte, daB auch wenn die Juroren ein bestimmtes Dia nicht fur die Veroffentlichung auswahlen, alle Dias sorgfaltig katalogisiert werden und ihnen ein fester Platz in der Forschungsbibliothek des Museums zugewiesen ast year in this space, I complained that a large number of glass wird. -

Ringworld 01 Ringworld Larry Niven CHAPTER 1 Louis Wu

Ringworld 01 Ringworld Larry Niven CHAPTER 1 Louis Wu In the nighttime heart of Beirut, in one of a row of general-address transfer booths, Louis Wu flicked into reality. His foot-length queue was as white and shiny as artificial snow. His skin and depilated scalp were chrome yellow; the irises of his eyes were gold; his robe was royal blue with a golden steroptic dragon superimposed. In the instant he appeared, he was smiling widely, showing pearly, perfect, perfectly standard teeth. Smiling and waving. But the smile was already fading, and in a moment it was gone, and the sag of his face was like a rubber mask melting. Louis Wu showed his age. For a few moments, he watched Beirut stream past him: the people flickering into the booths from unknown places; the crowds flowing past him on foot, now that the slidewalks had been turned off for the night. Then the clocks began to strike twenty-three. Louis Wu straightened his shoulders and stepped out to join the world. In Resht, where his party was still going full blast, it was already the morning after his birthday. Here in Beirut it was an hour earlier. In a balmy outdoor restaurant Louis bought rounds of raki and encouraged the singing of songs in Arabic and Interworld. He left before midnight for Budapest. Had they realized yet that he had walked out on his own party? They would assume that a woman had gone with him, that he would be back in a couple of hours. But Louis Wu had gone alone, jumping ahead of the midnight line, hotly pursued by the new day. -

Cosmos: a Spacetime Odyssey (2014) Episode Scripts Based On

Cosmos: A SpaceTime Odyssey (2014) Episode Scripts Based on Cosmos: A Personal Voyage by Carl Sagan, Ann Druyan & Steven Soter Directed by Brannon Braga, Bill Pope & Ann Druyan Presented by Neil deGrasse Tyson Composer(s) Alan Silvestri Country of origin United States Original language(s) English No. of episodes 13 (List of episodes) 1 - Standing Up in the Milky Way 2 - Some of the Things That Molecules Do 3 - When Knowledge Conquered Fear 4 - A Sky Full of Ghosts 5 - Hiding In The Light 6 - Deeper, Deeper, Deeper Still 7 - The Clean Room 8 - Sisters of the Sun 9 - The Lost Worlds of Planet Earth 10 - The Electric Boy 11 - The Immortals 12 - The World Set Free 13 - Unafraid Of The Dark 1 - Standing Up in the Milky Way The cosmos is all there is, or ever was, or ever will be. Come with me. A generation ago, the astronomer Carl Sagan stood here and launched hundreds of millions of us on a great adventure: the exploration of the universe revealed by science. It's time to get going again. We're about to begin a journey that will take us from the infinitesimal to the infinite, from the dawn of time to the distant future. We'll explore galaxies and suns and worlds, surf the gravity waves of space-time, encounter beings that live in fire and ice, explore the planets of stars that never die, discover atoms as massive as suns and universes smaller than atoms. Cosmos is also a story about us. It's the saga of how wandering bands of hunters and gatherers found their way to the stars, one adventure with many heroes.