Columbia University Task Force on Climate: Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fiscal Year 2018 Audited Financial Statements

350.ORG FINANCIAL STATEMENTS SEPTEMBER 30, 2018 350.ORG TABLE OF CONTENTS SEPTEMBER 30, 2018 Pages Independent Auditors’ Report ................................................................................................ 3-4 Financial Statements Statement of Financial Position ......................................................................................... 5 Statement of Activities ...................................................................................................... 6 Statement of Cash Flows ................................................................................................... 7 Notes to Financial Statements ............................................................................................ 8-13 7910 WOODMONT AVENUE 1150 18TH STREET, NW SUITE 500 SUITE 550 BETHESDA, MD 20814 WASHINGTON, DC 20036 (T) 301.986.0600 (T) 202.822.0717 Independent Auditors’ Report Board of Directors 350.Org Washington, D.C. We have audited the accompanying financial statements of 350.Org (the Organization) (a nonprofit organization), which comprise the statement of financial position as of September 30, 2018, and the related statements of activities and cash flows for the year then ended, and the related notes to the financial statements. Management’s Responsibility for the Financial Statements Management is responsible for the preparation and fair presentation of these financial statements in accordance with accounting principles generally accepted in the United States of America; this includes the design, -

Experimentation in Hunter's TEACHER EDUCATION PROGRAM Herbert C

Experimentation in Hunter's TEACHER EDUCATION PROGRAM Herbert C. Schueler The Teacher Education Program at Hunter College who by 1970 will represent one of every two children is quite different now from what it was a short ten years enrolled in our urban public schools. Volunteers are ago; ten years from now it will be quite different from recruited among the senior students to do their student the way it is now. It is a program, as much as any in teaching in special service, slum schools and to be the country, that keeps abreast of changing conditions prepared for full-time teaching vacancies the very next and needs. semester, in the same schools in which they receive their training. The training itself is intensified consid Traditionally, more than half of Hunter's under erably beyond the usual, with more than doubled super graduates, and an overwhelming majority of its grad vision by college and school personnel, increased teach uates are future or present teachers in our public ing opportunity, and an orientation to the community schools. No roll call of teachers in any New York served by the school led and organized by a member of school will fail to reveal a sizable contingent of Hunter the College staff. The personnel division of the Board . graduates. Therefore, in a very real sense, the develop of Education guarantees placement to the school in ment of public education in our area bears the mark of which the student teacher receives his training, pro Hunter's influence. This represents a responsibility vided he passes the usual examinations and is willing and a challenge that makes demands both frightening to accept the appointment. -

A Generation Without Representation How Young People Are Severely Underrepresented Among Legislators

A Generation Without Representation How Young People Are Severely Underrepresented Among Legislators By: Maggie Thompson and Anisha Singh September 2018 A Generation Without Representation How Young People Are Severely Underrepresented Among Legislators By: Maggie Thompson and Anisha Singh Contents 1 Introduction and Summary 3 Methodology 4 Historically Old Legislators 5 Older Means Less Diverse Race and Ethnicity Gender and Sexual Orientation Disability Religion Education, Military Experience, and Family 12 Young Legislators Are More Conservative Than Young Voters 13 An Overall Lack of Power 14 Why This Matters 16 What Can Be Done 20 Acknowledgments 21 Endnotes Introduction and Summary For a representative democracy to function, it is essential that government reflects its people—whether by race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, experience, age, or background. Diversity in leadership roles results in a more effective and fair government.1 By this measure, our democracy is dramatically failing younger Americans. Approximately 62 million Millennials were of voting age during the 2016 general election, according to Pew Research Center.2 In 2018, young voters, namely Millennials and Generation Z, are set to make up 34 percent of the eligible voting population.3 This gives young voters a larger share of the potential electorate than any other single generation.4 Yet, despite making up the largest potential voting bloc5 in the country today, young people are severely underrepresented at both the state and federal level. This representation gap impacts young people, and the issues they care about, directly. When elected officials aren’t representative of their constituents, this can lead to policies that are not responsive to the needs of the governed. -

A Review of the Current State of Research on the Water, Energy, and Food Nexus

A Review of the Current State of Research on the Water, Energy, and Food Nexus by Aiko Endo, Izumi Tsurita, Kimberly Burnett, And Pedcris M. Orencio Working Paper No. 2016-7 May 23, 2016 UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MANOA 2424 MAILE WAY, ROOM 540 • HONOLULU, HAWAI‘I 96822 WWW.UHERO.HAWAII.EDU WORKING PAPERS ARE PRELIMINARY MATERIALS CIRCULATED TO STIMULATE DISCUSSION AND CRITICAL COMMENT. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL AUTHORS. A Review of the Current State of Research on the Water, Energy, and Food Nexus Aiko Endo 1*, Izumi Tsurita2, Kimberly Burnett3, Pedcris M. Orencio4 1Research Department, Research Institute for Humanity and Nature, 457-4 Kamigamo-motoyama, Kita-ku, Kyoto 603-8047, Japan 2Department of Cultural Anthropology, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, The University of Tokyo, 3-8-1 Komaba, Meguro-ku, Tokyo, 153-8902, Japan 3 University of Hawaii Economic Research Organization, University of Hawaii at Manoa, 2424 Maile Way Saunders Hall 540 Honolulu, Hawaii, 96822, U.S.A. 4 Catholic Relief Service Philippines (Manila Office) Urban Disaster Risk Reduction Department, CBCP Building 470 Gen Luna Street, Intramuros, 1002 Manila, Philippines *Author to whom correspondence may be addressed. Tel: +81-75-707-2477; Fax: +81-75-707-2509. [email protected] Abstract: 1. Study region Asia, Europe, Oceania, North America, South America, Middle East and Africa. 2. Study focus The purpose of this paper is to review and analyze the water, energy, and food nexus and regions of study, nexus keywords and stakeholders in order to understand the current state of nexus research. -

Sriharsha V. Aradhya Phone: 917-826-7183 Email: [email protected] Website

Applied Physics & Applied Mathematics Columbia University, New York Sriharsha V. Aradhya Phone: 917-826-7183 Email: [email protected] Website: www.columbia.edu/~sva2107 Education Ph.D., Applied Physics Columbia University Oct 2013 Dissertation: Single Molecule Electronics and Mechanics New York, NY GPA: 4.00/4.00 Advisor: Prof. Latha Venkataraman M.S., Mechanical Engineering Purdue University Aug 2008 Thesis: Interfacial Bonding of Carbon Nanotubes West Lafayette, IN GPA: 3.73/4.00 Advisors: Prof. Timothy Fisher & Prof. Suresh Garimella B.Tech., Mechanical Engineering Indian Institute of Technology May 2006 Minor in Chemistry (IIT Madras), Chennai, India GPA: 8.25/10.00 Awards Graduate Student Gold Award - Materials Research Society (MRS) 2013 Best Paper Award - Society for Experimental Mechanics (SEM) 2012 Excellence in Graduate Research Travel Award - American Physical Society (APS) 2012 Education Fellowship - New York Academy of Sciences 2011 Fellow - Columbia Technology Ventures 2009 Inventor Medal & Best Intern Award - GE Global Research 2005 Summer Research Fellowship - JNCASR, Bangalore, India 2004 Young Engineering Fellowship - Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, India 2004 Patents 1. US Patent No. 8,262,835, ‘Method of bonding carbon nanotubes’ (issued Sep 2012). 2. US Patent No. 7,337,678, ‘MEMS flow sensor’ (issued Mar 2008). [Cited as a ‘key patent’ for MEMS technologies by the MEMS investor journal, Jun 2008] Research Experience Doctoral Research, Columbia University Sep 2008 - present Building a high-resolution conducting -

Observed and Projected Changes to the Precipitation Annual Cycle

1JULY 2017 M A R V E L E T A L . 4983 Observed and Projected Changes to the Precipitation Annual Cycle KATE MARVEL Columbia University, and NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, New York, New York MICHELA BIASUTTI Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University, Palisades, New York CÉLINE BONFILS AND KARL E. TAYLOR Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Livermore, California YOCHANAN KUSHNIR Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University, Palisades, New York BENJAMIN I. COOK NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, New York, New York (Manuscript received 2 August 2016, in final form 8 February 2017) ABSTRACT Anthropogenic climate change is predicted to cause spatial and temporal shifts in precipitation patterns. These may be apparent in changes to the annual cycle of zonal mean precipitation P. Trends in the amplitude and phase of the P annual cycle in two long-term, global satellite datasets are broadly similar. Model-derived fingerprints of externally forced changes to the amplitude and phase of the P seasonal cycle, combined with these observations, enable a formal detection and attribution analysis. Observed amplitude changes are in- consistent with model estimates of internal variability but not attributable to the model-predicted response to external forcing. This mismatch between observed and predicted amplitude changes is consistent with the sustained La Niña–like conditions that characterize the recent slowdown in the rise of the global mean temperature. However, observed changes to the annual cycle phase do not seem to be driven by this recent hiatus. These changes are consistent with model estimates of forced changes, are inconsistent (in one ob- servational dataset) with estimates of internal variability, and may suggest the emergence of an externally forced signal. -

Columbia University 600 West 125Th Street Project Information Session for Employment Opportunities for Minority, Women, and Local Resident Workers

Columbia University 600 West 125th Street Project Information Session for Employment Opportunities for Minority, Women, and Local Resident Workers Presentation for Construction Workers June 14, 2021 4:00 – 5:00 PM 1 AGENDA Welcome & Opening Remarks Lawrence Price Meet the Project Team Patrick Pagano Project Overview Patrick Pagano Minority, Women, & Local Resident Workforce Program Christine Salto Interview Session Schedule Patrick Pagano Applicant Requirements Patrick Pagano Workforce Process Harry Santiago 360 Degree Feedback Loop Harry Santiago OSHA Courses Christine Salto Contact Information 2 Questions & Answers WELCOME & OPENING REMARKS Lawrence Price Project Director Manhattanville Development Group Columbia University 3 MEET THE PROJECT TEAM v Columbia University • Lawrence Price, Project Director • Tanya Pope, AVP University Supplier Diversity • Christine Salto, Assistant Director, Compliance v Pavarini McGovern • Christopher Fillos, Senior Project Manager • Patrick Pagano, Project Manager v Crescent Consulting Associates, Inc. § Rohan de Freitas, Principal/CEO § Anthony Peterson, Project Executive § Jennifer Arroyo, Project Associate 4 PROJECT OVERVIEW v The Columbia University 600 West 125th Street project involves the construction of a 34-story residential apartment building. v The building will house Columbia University graduate students and faculty and has 5,000 square feet of ground-floor retail. v There is one floor of below-grade space for building services. v The building is designed by Renzo Piano Building Workshop; -

FYE Int 100120A.Indd

FirstYear & Common Reading CATALOG NEW & RECOMMENDED BOOKS Dear Common Reading Director: The Common Reads team at Penguin Random House is excited to present our latest book recommendations for your common reading program. In this catalog you will discover new titles such as: Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste, a masterful exploration of how America has been shaped by a hidden caste system, a rigid hierarchy of human rankings; Handprints on Hubble, Kathrn Sullivan’s account of being the fi rst American woman to walk in space, as part of the team that launched, rescued, repaired, and maintained the Hubble Space Telescope; Know My Name, Chanel Miller’s stor of trauma and transcendence which will forever transform the way we think about seual assault; Ishmael Beah’s powerful new novel Little Family about young people living at the margins of society; and Brittany Barnett’s riveting memoir A Knock at Midnight, a coming-of-age stor by a young laer and a powerful evocation of what it takes to bring hope and justice to a legal system built to resist them both. In addition to this catalog, our recently refreshed and updated .commonreads.com website features titles from across Penguin Random House’s publishers as well as great blog content, including links to author videos, and the fourth iteration of our annual “Wat Students Will Be Reading: Campus Common Reading Roundup,” a valuable resource and archive for common reading programs across the countr. And be sure to check out our online resource for Higher Education: .prheducation.com. Featuring Penguin Random House’s most frequently-adopted titles across more than 1,700 college courses, the site allows professors to easily identif books and resources appropriate for a wide range of courses. -

Eco-Anxiety: a Discourse Analysis of Media Representations of the School Strike for Climate

Running head: YOUTH CLIMATE CHANGE MOVEMENT 1 Eco-Anxiety: A Discourse Analysis of Media Representations of the School Strike for Climate Movement Brittany Smith This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the Honours degree of Bachelor of Psychological Science (Honours) School of Psychology Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences The University of Adelaide Submission Date: 29 September 2020 Word count: 9,083 YOUTH CLIMATE CHANGE MOVEMENT 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents .........................................................................................................................2, 3 List of Tables ....................................................................................................................................4 Abstract ............................................................................................................................................5 Declaration .......................................................................................................................................6 Contribution Statement ....................................................................................................................7 Acknowledgements ..........................................................................................................................8 Chapter 1: Introduction ....................................................................................................................9 1.1. Overview ...................................................................................................................9 -

The Pathway to a Green New Deal: Synthesizing Transdisciplinary Literatures and Activist Frameworks to Achieve a Just Energy Transition

The Pathway to a Green New Deal: Synthesizing Transdisciplinary Literatures and Activist Frameworks to Achieve a Just Energy Transition Shalanda H. Baker and Andrew Kinde The “Green New Deal” resolution introduced into Congress by Representative Alexandria Ocasio Cortez and Senator Ed Markey in February 2019 articulated a vision of a “just” transition away from fossil fuels. That vision involves reckoning with the injustices of the current, fossil-fuel based energy system while also creating a clean energy system that ensures that all people, especially the most vulnerable, have access to jobs, healthcare, and other life-sustaining supports. As debates over the resolution ensued, the question of how lawmakers might move from vision to implementation emerged. Energy justice is a discursive phenomenon that spans the social science and legal literatures, as well as a set of emerging activist frameworks and practices that comprise a larger movement for a just energy transition. These three discourses—social science, law, and practice—remain largely siloed and insular, without substantial cross-pollination or cross-fertilization. This disconnect threatens to scuttle the overall effort for an energy transition deeply rooted in notions of equity, fairness, and racial justice. This Article makes a novel intervention in the energy transition discourse. This Article attempts to harmonize the three discourses of energy justice to provide a coherent framework for social scientists, legal scholars, and practitioners engaged in the praxis of energy justice. We introduce a framework, rooted in the theoretical principles of the interdisciplinary field of energy justice and within a synthesized framework of praxis, to assist lawmakers with the implementation of Last updated December 12, 2020 Professor of Law, Public Policy and Urban Affairs, Northeastern University. -

Left Media Bias List

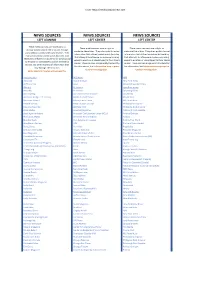

From -https://mediabiasfactcheck.com NEWS SOURCES NEWS SOURCES NEWS SOURCES LEFT LEANING LEFT CENTER LEFT CENTER These media sources are moderately to These media sources have a slight to These media sources have a slight to strongly biased toward liberal causes through moderate liberal bias. They often publish factual moderate liberal bias. They often publish factual story selection and/or political affiliation. They information that utilizes loaded words (wording information that utilizes loaded words (wording may utilize strong loaded words (wording that that attempts to influence an audience by using that attempts to influence an audience by using attempts to influence an audience by using appeal appeal to emotion or stereotypes) to favor liberal appeal to emotion or stereotypes) to favor liberal to emotion or stereotypes), publish misleading causes. These sources are generally trustworthy causes. These sources are generally trustworthy reports and omit reporting of information that for information, but Information may require for information, but Information may require may damage liberal causes. further investigation. further investigation. Some sources may be untrustworthy. Addicting Info ABC News NPR Advocate Above the Law New York Times All That’s Fab Aeon Oil and Water Don’t Mix Alternet Al Jazeera openDemocracy Amandla Al Monitor Opposing Views AmericaBlog Alan Guttmacher Institute Ozy Media American Bridge 21st Century Alaska Dispatch News PanAm Post American News X Albany Times-Union PBS News Hour Backed by Fact Akron Beacon -

Updated: 11/18/2016

Updated: 11/18/2016 Contents Columbia Global Centers | Amman .............................................................................................. 4 Director Biography ................................................................................................................................ 4 Center Space .......................................................................................................................................... 5 Regional Dimension .............................................................................................................................. 5 Networking and Contacts ...................................................................................................................... 5 Sampling of projects .............................................................................................................................. 7 Center Interests, Priorities and Thematic Focus .................................................................................. 13 Columbia Global Centers | Beijing ............................................................................................. 14 Center Space ........................................................................................................................................ 14 Regional Dimension ............................................................................................................................ 14 Networking and Contacts ...................................................................................................................