A Generation Without Representation How Young People Are Severely Underrepresented Among Legislators

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Columbia University Task Force on Climate: Report

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY TASK FORCE ON CLIMATE: REPORT Delivered to President Bollinger December 1, 2019 UNIVERSITY TASK FORCE ON CLIMATE FALL 2019 Contents Preface—University Task Force Process of Engagement ....................................................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary: Principles of a Climate School .............................................................................................................................. 4 Introduction: The Climate Challenge ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 The Columbia University Response ....................................................................................................................................................... 7 Columbia’s Strengths ........................................................................................................................................................................ 7 Columbia’s Limitations ...................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Why a School? ................................................................................................................................................................................... 9 A Columbia Climate School ................................................................................................................................................................. -

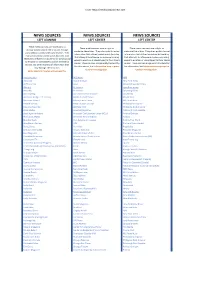

Left Media Bias List

From -https://mediabiasfactcheck.com NEWS SOURCES NEWS SOURCES NEWS SOURCES LEFT LEANING LEFT CENTER LEFT CENTER These media sources are moderately to These media sources have a slight to These media sources have a slight to strongly biased toward liberal causes through moderate liberal bias. They often publish factual moderate liberal bias. They often publish factual story selection and/or political affiliation. They information that utilizes loaded words (wording information that utilizes loaded words (wording may utilize strong loaded words (wording that that attempts to influence an audience by using that attempts to influence an audience by using attempts to influence an audience by using appeal appeal to emotion or stereotypes) to favor liberal appeal to emotion or stereotypes) to favor liberal to emotion or stereotypes), publish misleading causes. These sources are generally trustworthy causes. These sources are generally trustworthy reports and omit reporting of information that for information, but Information may require for information, but Information may require may damage liberal causes. further investigation. further investigation. Some sources may be untrustworthy. Addicting Info ABC News NPR Advocate Above the Law New York Times All That’s Fab Aeon Oil and Water Don’t Mix Alternet Al Jazeera openDemocracy Amandla Al Monitor Opposing Views AmericaBlog Alan Guttmacher Institute Ozy Media American Bridge 21st Century Alaska Dispatch News PanAm Post American News X Albany Times-Union PBS News Hour Backed by Fact Akron Beacon -

Alliances and Partnerships in American National Security

FOURTH ANNUAL TEXAS NATIONAL SECURITY FORUM ALLIANCES AND PARTNERSHIPS IN AMERICAN NATIONAL SECURITY ETTER-HARBIN ALUMNI CENTER THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN OCTOBER 12, 2017 8:30 AM - 8:45 AM Welcome by William Inboden, Executive Director of the Clements Center for National Security, and Robert Chesney, Director of the Robert Strauss Center for International Security and Law 8:45 AM - 10:00 AM • Panel One: Defense Perspectives Moderator: Aaron O’Connell, Clements Center and Department of History Aaron O'Connell is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Texas at Austin and Faculty Fellow at the Clements Center. Previously, he served as Director for Defense Policy & Strategy on the National Security Council at the White House, where he worked on a range of national security matters including security cooperation and assistance, defense matters in Africa, significant military exercises, landmine and cluster munitions policy, and high-technology matters affecting the national defense, such as autonomy in weapon systems. Dr. O’Connell is also the author of Underdogs: The Making of the Modern Marine Corps, which explores how the Marine Corps rose from relative unpopularity to become the most prestigious armed service in the United States. He is also the editor of Our Latest Longest War: Losing Hearts and Minds in Afghanistan, which is a critical account of U.S. efforts in Afghanistan since 2001. He has also authored a number of articles and book chapters on military affairs and the representations of the military in U.S. popular culture in the 20th century. His commentary has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, Foreign Affairs, and The Chronicle of Higher Education. -

Entrepreneurial Journalism Symposium

April 12, 2017 Event Connects Students with Innovators In a time of uncertainty and upheaval in the news industry, aspiring journalists must adapt Symposium Feature: and learn to drive change in the industry through innovation and entrepreneurship. Facebook Help Desk The James M. Cox Jr. Institute for Journalism Innovation, Management, and Leadership at Facebook set up a help desk during the the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication hosted its second symposium to give students one-on- Entrepreneurial Journalism Symposium dedicated to equipping student journalists with one time to learn about the tools tools and wisdom to thrive in the changing journalistic landscape. The symposium was held Facebook Media offers to independent on April 12, 2017 in conjunction with Startup Week in Athens. journalists. Tools included Signal which During the event, Dr. Keith Herndon, director of the Cox Institute, and Sullivan announced helps journalists aggregate trending the launch of the Independent Journalists Resource Coalition (IJRC), a working group stories, topics, and videos, and dedicated to the training and support of independent, freelance journalists. CrowdTangle which helps content creators compare story performance “If we want independent journalism to exist and to thrive, we have to provide these support across social media platforms. structures,” Sullivan said. “With them, we can incubate and create the spirit for all sorts of amazing, successful journalism.” “The Facebook help desk helped me explore more about how social media IJRC was created through a partnership between the Cox Institute, the National Press plays into new technologies, like Photographers Association, and the University of Georgia’s Small Business Development virtual reality – something I really Center. -

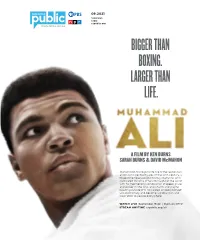

Bigger Than Boxing. Larger Than Life

09.2021 television radio ctpublic.org BIGGERBIGGER THAN THAN BOXING.BOXING. LARGERLARGER THAN THAN LIFE.LIFE. A FILM BY KEN BURNS SARAH BURNS & DAVID McMAHON TUNEA FILM IN BY OR KEN STREAM BURNS SARAHSUN BURNS SEPT & DAVID 19 8/ Mc7cMAHON STATION LETTERS GO HERE MuhammadTUNE Ali bringsIN ORto life one STREAM of the best-known and most indelible figures of the 20th century, a three-timeSUN heavyweight SEPT boxing 19 champion 8/7c who captivated millions of fans throughout the world withSTATION his mesmerizing LETTERS combination of speed, grace, and powerGO inHERE the ring, and charm and playful boasting outside of it. Ali insisted on being himself unconditionally and became a global icon and inspiration to people everywhere. WATCH LIVE September 19-22 | 8 pm on CPTV STREAM ANYTIME ctpublic.org/ali Corporate funding for MUHAMMAD ALI was provided by Bank of America. Major funding was provided by David M. Rubenstein. Major funding was also provided by The Arthur Vining Davis Foundations, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and by The Better Angels Society and by its members Alan and Marcia Docter; Mr. and Mrs. Paul Tudor Jones; The Fullerton Family Charitable Fund; Gilchrist and Amy Berg; The Brooke Brown Barzun Philanthropic Foundation, The Owsley Brown III Philan thropic Foundation and The Augusta Brown Holland Philanthropic Foundation; Perry and Donna Golkin; John and Leslie McQuown; John and Catherine Debs; Fred and Donna Seigel; Susan and John Wieland; Stuart and Joanna Brown; Diane and Hal Brierley; Fiddlehead Fund; Rocco and Debby Landesman; McCloskey Family Charitable Trust; Mauree Jane and Mark Perry; and Donna and Richard Strong. -

Spotlight: 3Rd Annual How DE&I Drives Innovation

Greg Berlanti Albert Cheng Tara Duncan Writer/Producer/Director Amazon Studios/HRTS Board Freeform/HRTS Board HRTS VIRTUAL Spotlight: 3rd annual How DE&I Drives Innovation TUESDAY, APRIL 20, 2021 1:00-2:30 PM PT (4:00-5:30 PM ET / 9:00-10:30 PM GMT) Presented By: Contributing Sponsor: Moderator: Karen Gray A+E Networks Group CO CHAIRS/Officers: Paul Buccieri, (A+E Networks Group), Dan Erlij, (UTA), Kelly Goode, (Warner Bros Television), Greg Lipstone, (Propagate Content), and Odetta Watkins, (Warner Bros Television) Robin Roberts Tanya Saracho Carlos Watson ABC News/Rock’n Robin Productions Creator/Showrunner/Director OZY Media TRIM BLEED 03/22/21 06:20:48 PM MBAUGH PDFX1A 03/22/21 06:20:48PMMBAUGHPDFX1A HOLLYWOOD_RADIO_TV_SOCIETY CYAN MAGENTA SUPPORT ANDADVANCE SUPPORT PROUD TO SUPPORT PROUD TO AND THEIR WORK TO AND THEIRWORK YELLOW H DISCOVERY DISCOVERY OUR INDUSTRY BLACK R ©2021 DISCOVERY, INC. DISCOVERY, ©2021 7 T S IS TRIM: 5.5”X8.5”•BLEED:5.75”8.75” HRTS HRTS 100 75 50 25 10 5 100 75 50 25 10 5 100 75 50 25 10 5 100 75 50 25 10 5 HOLLYWOOD_RADIO_TV_SOCIETY HRTS 03/22/21 06:20:48 PM MBAUGH PDFX1A TRIM: 5.5” X 8.5” • BLEED: 5.75” X 8.75” BLEED TRIM 5 10 25 50 DISCOVERY IS 75 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Welcomes you 100 PROUD TO SUPPORT 5 10 25 50 75 HRTS President HRTS Chair Odetta Watkins Dan Erlij 100 Warner Bros. Television UTA 5 HRTS 10 AND THEIR WORK TO 25 50 HRTS VP HRTS Secretary HRTS Treasurer SUPPORT AND ADVANCE 75 Francesca Orsi Charlie Andrews Alejandro Uribe HBO FOX Exile Content OUR INDUSTRY 100 5 David Acosta Kate Adler Bela -

2019-2020 Annual Report Table of Contents

2019-2020 ANNUAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS WHO WHAT WHERE WE ARE WE’RE DOING WE’RE GOING 5 Letter from the Dean 17 Responding to the 39 2020-21 Preview 6 CDM Programs COVID-19 Pandemic 7 By the Numbers 20 Supporting the Mission 10 School of Cinematic Arts 21 Global Learning 12 School of Computing 23 Engaging and Educating 14 School of Design Youth 24 Visiting Speakers 26 Faculty Grants 28 Faculty Publications 32 Faculty Screenings and Film Recognition 35 Faculty Exhibitions 36 Student and Alumni Recognition 37 CDM in the News LETTER WHO FROM THE DEAN As I write this letter wrapping up the 2019-20 academic year, we remain in a global pandemic that has profoundly altered our lives. While many things have changed, some stayed the same: our CDM community worked hard, showed up for one another, and continued WE to advance their respective fields. A year that began like many others changed swiftly on March 11th when the University announced that spring classes would run remotely. By March 28th, the first day of spring quarter, we had moved 500 CDM courses online thanks to the diligent work of our faculty, staff, and instructional designers. ARE But CDM’s work went beyond the (virtual) classroom. We mobilized our makerspaces to assist in the production of personal protective equipment for Illinois healthcare workers, participated in COVID-19 research initiatives, and were inspired by the innovative ways our student groups learned to network. You can read more about our The College of Computing and Digital Media is dedicated to providing students an response to the COVID-19 pandemic on pgs. -

EDITION Saint Marcus Lutheran School

MILWAUKEE COMMUNITY JOURNAL Associated Bank sponsors MIAD Pre-College VOL. XXXVIII NO.8 JULY 9, 2021 50 CENTS program EDITIONEDITIONBULK RATE U.S. POSTAGE MILWAUKEE, WISCONSIN PERMIT 4668 WEEKENDWEEKENDfamily Siebert Lutheran Foundation, time We Raise Foundation Awards $300,000 Grant to St. Marcus Lutheran School received a $300,000 grant on Thursday, June 10, 2021 the We Raise Foundation and the Saint Siebert Lutheran Foundation that will be used to expand communitybuilding efforts Marcus designed to provide stable households and productive learning environments for students. Pictured presenting Lutheran a ceremonial check to St. Marcus scholars are (from left) Paul Miles, president of We Raise Foundation; Avana Kelly, 2021 graduate of St. Marcus; Donte Edwards, 2021 graduate of St. School Marcus; ShaRonn Kelly, fifth-grade scholar at St. Marcus; and Charlotte John-Gomez, president of the to expand community Siebert Luterhan Foundation. engagement work stable households and productive learning envi- be influenced by life events unrelated to school. ronments. These include: A stable home, employment, and abundance of Project aims to build stable ● Financial literacy classes healthy food all affect a child’s academics. ● One-on-one financial “We Raise Foundation is pleased to partner households that support coaching/accountability with Siebert Lutheran Foundation to invest in ● Homeownership workshops the work being done at St. Marcus Lutheran productive learning ● Job networking School,” said Paul Miles, President and CEO of ● Peer-to-Peer Community Support We Raise Foundation. environments ● Crisis Stabilization (healthy food, “Under the extraordinary leadership of Henry supplies, shelter) Tyson and his team, St. Marcus sets the highest St. Marcus Lutheran School an- The community engagement specialist will fur- standards of academic performance and then ther engage leaders and organizations in the creates innovative solutions to help its students nounced Thursday, June 10th, a community to build effective collaborations and meet them. -

Law, Virtual Reality, and Augmented Reality

UNIVERSITY of PENNSYLVANIA LAW REVIEW Founded 1852 Formerly AMERICAN LAW REGISTER © 2018 University of Pennsylvania Law Review VOL. 166 APRIL 2018 NO. 5 ARTICLE LAW, VIRTUAL REALITY, AND AUGMENTED REALITY MARK A. LEMLEY† & EUGENE VOLOKH†† Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) are going to be big—not just for gaming but for work, for social life, and for evaluating and buying real-world products. Like many big technological advances, they will in some ways challenge legal doctrine. In this Article, we will speculate about some of these upcoming challenges, asking: † William H. Neukom Professor, Stanford Law School; partner, Durie Tangri LLP. Article © 2018 Mark A. Lemley & Eugene Volokh. †† Gary T. Schwartz Professor of Law, UCLA School of Law; academic affiliate, Mayer Brown LLP. Thanks to Sam Bray, Ryan Calo, Anupam Chander, Julie Cohen, Kristen Eichensehr, Nita Farahany, James Grimmelmann, Rose Hagan, Claire Hill, Chad Huston, Sarah Jeong, Bill McGeveran, Emily Murphy, Lisa Ouellette, Richard Re, Zahr Said, Rebecca Tushnet, Vladimir Volokh, and the participants at the UC Davis conference on Future-Proofing Law, the Stanford Law School conference on regulating disruption, the Internet Law Works in Progress Conference, and workshops at Stanford Law School, Duke Law School, the University of Minnesota Law School, and the University of Washington for comments on prior drafts; and to Tyler O’Brien and James Yoon for research assistance. (1051) 1052 University of Pennsylvania Law Review [Vol. 166: 1051 (1) How might the law treat “street crimes” in VR and AR—behavior such as disturbing the peace, indecent exposure, deliberately harmful visuals (such as strobe lighting used to provoke seizures in people with epilepsy), and “virtual groping”? Two key aspects of this, we will argue, are the Bangladesh problem (which will make criminal law very hard to practically enforce) and technologically enabled self-help (which will offer an attractive alternative protection to users, but also a further excuse for real-world police departments not to get involved). -

USC Dornsife in the News Archive - 2016

USC Dornsife in the News Archive - 2016 December December 22, 2016 The Conversation published an op-ed by Khatera Sahibzada, adjunct lecturer in applied psychology, on the practical application of a 13th century Sufi saying to managerial feedback in the present. "As long as managers always ensure their feedback is unbiased, essential and civil, it’s almost certain to be effective and help an employee grow," Sahibzada wrote. The New York Times quoted Stanley Rosen, professor of political science, on the efforts of Chinese movie production companies to reach worldwide audiences with the film "The Great Wall." USA Today quoted Matthew Kahn, professor of economics and spatial sciences, on President-elect Donald Trump's economic goals related to China. UPROXX quoted Robert English, associate professor of international relations, Slavic languages and literature, and environmental studies, on the reasons Russian media may have reported on the opening of an embassy by the California secessionist group Yes California. December 21, 2016 The Korea Times published commentary by Kyung Moon Hwang, professor of history and East Asian languages and cultures, on why the current political turmoil in South Korea should not be considered a "revolution." Hwang argues the final steps towards true democratization will finally yield the benefits from the country's previous revolution. December 20, 2016 NPR Chicago affiliate WBEZ-FM highlighted research by Duncan Ermini Leaf of the USC Schaeffer Center, Maria Jose Prados of USC Dornsife 's Center for Economic and Social Research and colleagues on the long-term benefits of preschool. The study, led by Nobel Prize winner James Heckman, found life cycle benefits for children enrolled in high-quality preschool programs, general benefits for parents, and savings for the community as a whole. -

50Womencan Bios

THE COHORT BIOS THE COHORT Aisling Chin-Yee Aisling Chin-Yee is an award winning producer, writer, and director based in Montreal, Canada. Working closely with writers and directors with unique, unapologetic visions in both feature films and documentaries from around the world. She began her production career as an associate producer at the National Film Board of Canada in 2006, joined Prospector Films as producer and director in 2010. Aisling founded Fluent Films in early 2016. She co-created, alongside actor Mia Kirshner, #AfterMeToo, a symposium, series and report that analyzes the issue of sexual misconduct in the entertainment industry. She produced the short films, Three Mothers (2008), The Color of Beauty (2010) Sorry, Rabbi (2011). In 2013 she produced the award winning feature film, Rhymes for Young Ghouls, which was a TIFF Top 10 film, and won Best Director at the Vancouver International Film Festival, as well as the award-winning feature documentary Last Woman Standing that same year. 2014 marked her year as writer and director with the short film, Sound Asleep that Canada brought to the Cannes Film Market and premiered at Lucerne International Film Festival. In 2015, she directed the multi-award winning documentary Synesthesia and produced the gritty urban drama, The Saver that released in Spring 2016.Aisling produced the US series and feature, Lost Generation, with LA based company New Form Digital starring Katie Findlay (How to Get Away with Murder, Man Seeking Woman), Callum Worthy, and Melissa O'Neil, that hit VOD platforms autumn 2016 across North America. With Prospector Films, she produced the documentary Inside these Walls which released on CBC October 2016. -

The Constitutionality and Future of Sex Reassignment Surgery in United States Prisons, 28 Hastings Women's L.J

Hastings Women’s Law Journal Volume 28 Article 6 Number 1 Winter 2017 Winter 2017 The onsC titutionality and Future of Sex Reassignment Surgery in United States Prisons Brooke Acevedo Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hwlj Part of the Law and Gender Commons Recommended Citation Brooke Acevedo, The Constitutionality and Future of Sex Reassignment Surgery in United States Prisons, 28 Hastings Women's L.J. 81 (2017). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hwlj/vol28/iss1/6 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Women’s Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ACEVEDO_MACRO (DO NOT DELETE) 1/6/2017 10:28 AM The Constitutionality and Future of Sex Reassignment Surgery in United States Prisons Brooke Acevedo* Just as a prisoner may starve if not fed, he or she may suffer or die if not provided adequate medical care. A prison that deprives prisoners of basic sustenance, including adequate medical care, is incompatible with the concept of human dignity and has no place in civilized society.** I. INTRODUCTION No inmate in the United States has successfully undergone sex reassignment surgery1 while incarcerated.2 However, in a groundbreaking settlement agreement, the California Department of Corrections has agreed to pay for inmate Shiloh Quine to undergo sex reassignment surgery.3 The terms of the settlement limit its application exclusively to Quine.4 However, as a result of the agreement, the state has also produced strict guidelines for transgender5 inmates seeking to undergo sex reassignment * J.D.