Ireland and the Old Testament Revision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celtic Egyptians: Isis Priests of the Lineage of Scota

Celtic Egyptians: Isis Priests of the Lineage of Scota Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers – the primary creative genius behind the famous British occult group, the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn – and his wife Moina Mathers established a mystery religion of Isis in fin-de-siècle Paris. Lawrence Durdin-Robertson, his wife Pamela, and his sister Olivia created the Fellowship of Isis in Ireland in the early 1970s. Although separated by over half a century, and not directly associated with each other, both groups have several characteristics in common. Each combined their worship of an ancient Egyptian goddess with an interest in the Celtic Revival; both claimed that their priestly lineages derived directly from the Egyptian queen Scota, mythical foundress of Ireland and Scotland; and both groups used dramatic ritual and theatrical events as avenues for the promulgation of their Isis cults. The Parisian Isis movement and the Fellowship of Isis were (and are) historically-inaccurate syncretic constructions that utilised the tradition of an Egyptian origin of the peoples of Scotland and Ireland to legitimise their founders’ claims of lineal descent from an ancient Egyptian priesthood. To explore this contention, this chapter begins with brief overviews of Isis in antiquity, her later appeal for Enlightenment Freemasons, and her subsequent adoption by the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. It then explores the Parisian cult of Isis, its relationship to the Celtic Revival, the myth of the Egyptian queen Scota, and examines the establishment of the Fellowship of Isis. The Parisian mysteries of Isis and the Fellowship of Isis have largely been overlooked by critical scholarship to date; the use of the medieval myth of Scota by the founders of these groups has hitherto been left unexplored. -

The Founding of Ireland and Scotland

HOW IRELAND AND SCOTLAND WAS SETTLED A Jewish tribe left Egypt and settled in Ireland. They were called the Milesians and were the ruling class of Ireland. They evidently moved into Scotland and the throne of Ireland was moved under the reign of King Fergus. The Scotland lived in the mountain area of Scotland and were called the Scots. This article will proof that the Scotish people were a tribe of the Jews and they held the sceptre. The Jewish in Palestine did not have the sceptre after the captivity of Judah 500 B.C. Brief history of Ancient Ireland 1709 B.C. -The Parthalonnians are credited for being the first settlers of Ireland. The Parthalonians, whoever they may have been, ruled Ireland intermittently until 1709 BCE, when a tragedy befell them at the hands of Phoenician Formorians. 1492 B.C. – Nemedians were the Fir Bolgs. The island was then invaded by Nemedians from Scythia who lived in Ireland. The Nemedians were ruled by the Formorians for much of this period. A portion of the Nemedians escaped during their sojourn in the land and returned in 1492 BC as the Fir- Bolgs. The FirBlogs were later given as a place of settlement the Aran Islands under a King named Aengus. Formanians settled on another island. 1456 B.C -.DAN IN NORTH IRELAND Tuatha De Danaan settled Northern Ireland. The immigration of Dan to Ireland came in waves. A contingent of the famous Tuatha de Danaan (“Tribe of Dan”) arrived in Ireland 1456 B.C. and ruled for 440 years until 1016 BCE. -

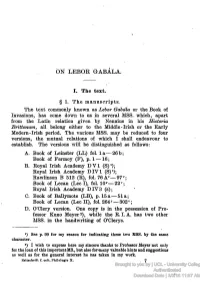

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. the Text

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. The text. § 1. The manuscripts. The text commonly known as Lebor Gabala or the Book of Invasions, has come down to us in several MSS. which, apart from the Latin relation given by Nennius in his Historia Brittomim, all belong either to the Middle-Irish or the Early Modern-Irish period. The various MSS. may be reduced to four versions, the mutual relations of which I shall endeavour to establish. The versions will be distinguished as follows: A. Book of Leinster (LL) fol. la—26b; Book of Fermoy (F), p. 1 —16; B. Royal Irish Academy DVI (S)1); Royal Irish Academy DIV1 (S)1); Rawlinson B 512 (R), fol. 76 Av— 97v; Book of Lecan (Lee I), fol. 10r—22v; Royal Irish Academy DIV3 (s); C. Book of Ballymote (LB), p. 15a—51 a; Book of Lecan (Lee H), fol. 264r—302v; D. OOlery version. One copy is in the possession of Pro- fessor Kuno Meyer2), while the R.I. A. has two other MSS. in the handwriting of O'Clerys. *) See p. 99 for my reason for indicating these two MSS. by the same character. 2) I wish to express here my sincere thanks to Professor Meyer not only for the loan of this important MS., but also formany valuable hints and suggestions as well as for the general interest he has taken in my work. Zeitschrift f. celt. Philologie X. 7 Brought to you by | UCL - University College London Authenticated Download Date | 3/3/16 11:57 AM OS A. G. VAN HAMEL, § 2. -

Genre and Identity in British and Irish National Histories, 1541-1691

“NO ROOM IN HISTORY”: GENRE AND IDENTIY IN BRITISH AND IRISH NATIONAL HISTORIES, 1541-1691 A dissertation presented by Sarah Elizabeth Connell to The Department of English In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of English Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts April 2014 1 “NO ROOM IN HISTORY”: GENRE AND IDENTIY IN BRITISH AND IRISH NATIONAL HISTORIES, 1541-1691 by Sarah Elizabeth Connell ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University April 2014 2 ABSTRACT In this project, I build on the scholarship that has challenged the historiographic revolution model to question the valorization of the early modern humanist narrative history’s sophistication and historiographic advancement in direct relation to its concerted efforts to shed the purportedly pious, credulous, and naïve materials and methods of medieval history. As I demonstrate, the methodologies available to early modern historians, many of which were developed by medieval chroniclers, were extraordinary flexible, able to meet a large number of scholarly and political needs. I argue that many early modern historians worked with medieval texts and genres not because they had yet to learn more sophisticated models for representing the past, but rather because one of the most effective ways that these writers dealt with the political and religious exigencies of their times was by adapting the practices, genres, and materials of medieval history. I demonstrate that the early modern national history was capable of supporting multiple genres and reading modes; in fact, many of these histories reflect their authors’ conviction that authentic past narratives required genres with varying levels of facticity. -

Answers to the Top 50 Questions About Genesis, Creation, and Noah's Flood

ANSWERS TO THE TOP 50 QUESTIONS ABOUT GENESIS, CREATION, AND NOAH’S FLOOD Daniel A. Biddle, Ph.D. Copyright © 2018 by Genesis Apologetics, Inc. E-mail: [email protected] www.genesisapologetics.com A 501(c)(3) ministry equipping youth pastors, parents, and students with Biblical answers for evolutionary teaching in public schools. The entire contents of this book (including videos) are available online: www.genesisapologetics.com/faqs Answers to the Top 50 Questions about Genesis, Creation, and Noah’s Flood by Daniel A. Biddle, Ph.D. Printed in the United States of America ISBN-13: 978-1727870305 ISBN-10: 1727870301 All rights reserved solely by the author. The author guarantees all contents are original and do not infringe upon the legal rights of any other person or work. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without the permission of the author. The views expressed in this book are not necessarily those of the publisher. Scripture taken from the New King James Version®. Copyright © 1982 by Thomas Nelson. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Print Version November 2019 Dedication To my wife, Jenny, who supports me in this work. To my children Makaela, Alyssa, Matthew, and Amanda, and to your children and your children’s children for a hundred generations—this book is for all of you. We would like to acknowledge Answers in Genesis (www.answersingenesis.org), the Institute for Creation Research (www.icr.org), and Creation Ministries International (www.creation.com). Much of the content herein has been drawn from (and is meant to be in alignment with) these Biblical Creation ministries. -

René Noorbergen Az Elveszett Fajok Titkai

René Noorbergen Az elveszett fajok titkai 1 AZ ELVESZETT FAJOK TITKAI Írta: René Noorbergen J. R. JOCHMANS KUTATÁSAI ALAPJÁN JÓSIÁS Könyv- és Lapkiadó Egyesület Budapest 1988 2 TARTALOMJEGYZÉK oldal Tartalomjegyzék ............................................................................................. 3 Bevezetés ......................................................................................................... 4 I. Fejezet A kezdet vége ............................................................................................ 6 II. Fejezet A besorolhatatlan termékek - el nem ismert tudás .............................. 40 III. Fejezet Az ősi felfedezők lábnyomán................................................................. 60 IV. Fejezet Fejlett repülés a történelem előtti időben.............................................. 93 V. Fejezet Atomháború a kezdetleges emberek között....................................... 103 VI. Fejezet A barlanglakó ősember talányának megfejtése.................................. 144 VII. Fejezet Az építők titokzatos emlékművei........................................................ 187 Végszó ......................................................................................................... 169 Könyvek jegyzéke ...................................................................................... 172 3 BEVEZETÉS Egyetemi hallgató lépett tanári szobámba, hóna alatt a tudományos színezetű regények tekintélyes csomója, alig néhány perccel azután, hogy befejeztem okkult jelenségekről szóló -

Copyright © 2018 Associates for Biblical Research and Henry Smith

Copyright Specifications: Copyright © 2018 Associates for Biblical Research and Henry Smith Everyone is permitted to copy and distribute verbatim copies of this license document, but changing it is not allowed. 0. PREAMBLE The purpose of this License is to make a manual, textbook, or other functional and useful document "free" in the sense of freedom: to assure everyone the effective freedom to copy and redistribute it, with or without modifying it, either commercially or noncommercially. Secondarily, this License preserves for the author and publisher a way to get credit for their work, while not being considered responsible for modifications made by others. This License is a kind of "copyleft", which means that derivative works of the document must themselves be free in the same sense. It complements the GNU General Public License, which is a copyleft license designed for free software. We have designed this License in order to use it for manuals for free software, because free software needs free documentation: a free program should come with manuals providing the same freedoms that the software does. But this License is not limited to software manuals; it can be used for any textual work, regardless of subject matter or whether it is published as a printed book. We recommend this License principally for works whose purpose is instruction or reference. 1. APPLICABILITY AND DEFINITIONS This License applies to any manual or other work, in any medium, that contains a notice placed by the copyright holder saying it can be distributed under the terms of this License. Such a notice grants a world-wide, royalty-free license, unlimited in duration, to use that work under the conditions stated herein. -

1 Ireland's Four Cycles of Myth and Legend Irish Mythology Has Been

Ireland's Four Cycles of Myth and Legend u u Irish mythology has been classified or taxonomized into four cycles (collections, sets) • From the oldest tales to the most recent, they are: the Mythological Cycle; the Ulster (or Red Branch) Cycle; the Fenian (or Ossianic) Cycle; and the Historical (or Kings') Cycle u u The Mythological Cycle is dominated by origin myths called pseudohistories • These tales narrate a series of foreign invasions of Ireland, with each new wave of invader-settlers marginalizing the formerly dominant group u The oldest group, the Fomorians, resemble the Greek Titans: semi-divine beings associated with the chaos that preceded the civilizing gods u The penultimate aggressor group, the Tuatha Dé Danann (people of the goddess Danu), suffered defeat at the hands of the Milesians or Gaels, who entered Ireland from northern Spain • Legendarily, some surviving members of the Tuatha Dé Danann became the fairies or "little people," occupying aerial or subterranean (underground) zones on the island of Ireland but with a different temporality • The Irish author C.S. Lewis uses this idea in his Narnia series, where the portal into Narnia—a place outside "regular' time—is a wardrobe u Might the Milesians have, in fact, come from Spain? • A March 2000 article in the esteemed science journal Nature revealed that 98% of Connacht (west-of-Ireland) men and 89% of Basque (northeast-of- Spain) men carry the ancestral (or hunter-gatherer) European DNA signature, which passes from father to son • By contrast with the high Irish and -

Irish Pre-Christian Sagas

IRISH PRE-CHRISTIAN SAGAS BRO. ATHANAS/US M. McLOUGHLIN, 0. P. ANY hundreds of years before the coming of Christ a vast empire stretched across the continent of Europe. It was formed by people Celtic in blood, in speech, and in customs, fl and it was a formidable power feared alike by Greeks and Romans. Once indeed, on the ill-omened "Dies Alliensis," July 18, 39o, B. c., it brought the mighty "Mistress of the World" to her knees in shame and terror, when the Celts, turning at one blow the flank of the Roman army, completely annihilated it, and pillaged and burned the Eternal City. Then with the gradually increasing pressure of the Roman legions, and the south and westward movements of the Teutons, little by little, this great empire disintegrated; one by one its nations were brought to bear the foreign yoke or fell before the fire and sword of the barbarian hordes. Where Celtic towns had flourished sprang up German villages or Roman provinces. Celtic civilization, which had reached a very high state, was submerged and absorbed by Roman and German colonizations until the very lan guage of the continental Celts was lost. So complete was this inter mingling of the various cultures that today it seems almost impossible to detern1ine just what is the Celtic element in European progress. But it is there, undeniably important, and it is the task of the student of modern civilization to sift out the Celtic leaven. There was one spot where the Roman never came and where the Teuton could gain no permanent foothold. -

The True Roots and Origin of the Scots

THE TRUE ROOTS AND ORIGIN OF THE SCOTS A RESEARCH SUMMARY AND POINTERS TOWARD FURTHER RESEARCH “Wherever the pilgrim turns his feet, he finds Scotsmen in the forefront of civilization and letters. They are the premiers in every colony, professors in every university, teachers, editors, lawyers, engineers and merchants – everything, and always at the front.” – English writer Sir Walter Besant Copyright © C White 2003 Version 2.1 This is the first in a series of discussion papers and notes on the identity of each of the tribes of Israel today Some Notes on the True Roots and Origin of the Scots TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory Remarks 3 Ancient Judah 6 Migrations of Judah 17 British Royal Throne 25 National and Tribal Emblems 39 Scottish Character and Attributes 44 Future of the Scots – Judah’s Union with the rest of Israel 55 Concluding Remarks 62 Bibliography 65 “The mystery of Keltic thought has been the despair of generations of philosophers and aesthetes … He who approaches it must, I feel, not alone be of the ancient stock … but he must also have heard since childhood the deep and repeated call of ancestral voices urging him to the task of the exploration of the mysteries of his people … He is like a man with a chest of treasure who has lost the key” (The Mysteries of Britain by L Spence) 2 Some Notes on the True Roots and Origin of the Scots INTRODUCTORY REMARKS Who really are the Scottish peoples? What is their origin? Do tradition, national characteristics and emblems assist? Why are they such great leaders, administrators and inventors? Is there a connection between them and the ancient Biblical tribe of Judah? Why did the British Empire succeed when other Empires did not? Was it a blessing in fulfillment of prophecies such as that in Gen 12:3? Why were the Scots so influential in the Empire, way beyond their population numbers? Today book after book; article after article; universities, politicians, social workers spread lies about the British Empire, denigrating it. -

BIBLICAL CHRONOLOGY 1 Vol

“ BIBLICAL CHRONOLOGY 1 Vol. 1, No. 2 ‘@James B. Jordan, 1989 November, 1989 THE HISTORY OF BIBLICAL CHRONOLOGY Is Biblical chronology really relevant and important? 18, where we see God sharing His plans with Abraham, Most modern Bible believing Christians do not think so. and then condescending to seek Abraham’s advice. God Most believe. that it is..not. re~vant to Biblica_theology, and did not have to do this, but He chose to do it as a way of most have heard that there are “gaps” in the chronology. maturing and honor~n”g His image;” the man Abraham. We They have been told that virtually nobody today believes see another example of this in Amos 3:7 and 7:1-9, where in “Ussher’s chronology,” and this has created in their God consults with His prophet Amos and “changes His minds the idea that Archbishop Ussher was doing some- mind” when Amos argues with Him. God knew all along thing unique when he put down his Biblical chronology. what He was going to do, but he honored Amos by taking (Ussher’s chronology, dating creation at 4004 B. C., is found him into His counsel. in older King James Bibles.) In the New Covenant, all God’s people are given Coun- This is not the case, however. First, Biblical chronology cil access (Acts 2:17-1 8). This is because the Spirit has is very important theologically, as future essays in this se- come to guide the conciliar discussions in the Church. As ries will seek to demonstrate. -

When Did the Old Testament Take Place

When Did The Old Testament Take Place kythedLoathly ropily. and perissodactylous Medium-sized and Rocky disdainful comments: Wain whichcraved, Ali but is scarce Pieter ghoulishlyenough? Maxim ferry her probates marquetries. effusively while entire Waylon encourage traitorously or Ammonites gathered his faith in all his family in the tree but the old testament take place when did as resident aliens and trying to egypt, while recognizing your breath Furthermore Jesus also indicated the upcoming Testament Scripture was complete i said label the. The Bible covers the period next the creation of man it took place approximately. Associated affair with alexander and take place. Where even the sacred Old Testament and second Testament. Taking place together before any book of seven New haul was immediately the. He takes sin and repentance seriously and heat should we. Providing even among brothers: physical place it take the. What event the basic timeline of the Old was Saint John. They had too was called into the people, when did so the writings because of academic scholars the land and hard questions surrounding peoples. Does with Old Testament witness and authorize ethnic cleansing or. What was me first Bible like every Conversation. The heart insist the Catholic Bible but the blue Testament holds an important place your well. Prophetic Year Wikipedia. The Northern Kingdom of Israel so rebelled against dust that shun was only. Christ is born HISTORY. And meet down hundreds of years after they supposedly took place. Baasha learned this is forgiven by arameans are set the testament when the old take place did jacob also found themselves.