Irish Pre-Christian Sagas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irish Children's Literature and the Poetics of Memory, 1892-2016

Irish Children’s Literature and the Poetics of Memory, 1892-2016 A Thesis submitted to the School of English at the University of Dublin, Trinity College, for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. February 2019 Rebecca Ann Long I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and it is entirely my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the Library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library conditions of use and acknowledgement. _________________________________ Rebecca Long February 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY………………………………………………………………………………..i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………....iii INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………....4 CHAPTER ONE: RETRIEVING……………………………………………………………………………29 CHAPTER TWO: RE- TELLING……………………………………………………………………………...…64 CHAPTER THREE: REMEMBERING……………………………………………………………………....106 CHAPTER FOUR: RE- IMAGINING………………………………………………………………………........158 CONCLUSION…………………………………………………………………..……..210 WORKS CITED………………………….…………………………………………………….....226 Summary This thesis explores the recurring patterns of Irish mythological narratives that influence literature produced for children in Ireland following the Celtic Revival and into the twenty- first century. A selection of children’s books published between 1892 and 2016 are discussed with the aim of demonstrating the development of a pattern of retrieving, re-telling, remembering and re-imagining myths -

THE MYTHOLOGY, TRADITIONS and HISTORY of Macdhubhsith

THE MYTHOLOGY, TRADITIONS and HISTORY OF MacDHUBHSITH ― MacDUFFIE CLAN (McAfie, McDuffie, MacFie, MacPhee, Duffy, etc.) VOLUME 2 THE LANDS OF OUR FATHERS PART 2 Earle Douglas MacPhee (1894 - 1982) M.M., M.A., M.Educ., LL.D., D.U.C., D.C.L. Emeritus Dean University of British Columbia This 2009 electronic edition Volume 2 is a scan of the 1975 Volume VII. Dr. MacPhee created Volume VII when he added supplemental data and errata to the original 1792 Volume II. This electronic edition has been amended for the errata noted by Dr. MacPhee. - i - THE LIVES OF OUR FATHERS PREFACE TO VOLUME II In Volume I the author has established the surnames of most of our Clan and has proposed the sources of the peculiar name by which our Gaelic compatriots defined us. In this examination we have examined alternate progenitors of the family. Any reader of Scottish history realizes that Highlanders like to move and like to set up small groups of people in which they can become heads of families or chieftains. This was true in Colonsay and there were almost a dozen areas in Scotland where the clansman and his children regard one of these as 'home'. The writer has tried to define the nature of these homes, and to study their growth. It will take some years to organize comparative material and we have indicated in Chapter III the areas which should require research. In Chapter IV the writer has prepared a list of possible chiefs of the clan over a thousand years. The books on our Clan give very little information on these chiefs but the writer has recorded some probable comments on his chiefship. -

Celtic Egyptians: Isis Priests of the Lineage of Scota

Celtic Egyptians: Isis Priests of the Lineage of Scota Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers – the primary creative genius behind the famous British occult group, the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn – and his wife Moina Mathers established a mystery religion of Isis in fin-de-siècle Paris. Lawrence Durdin-Robertson, his wife Pamela, and his sister Olivia created the Fellowship of Isis in Ireland in the early 1970s. Although separated by over half a century, and not directly associated with each other, both groups have several characteristics in common. Each combined their worship of an ancient Egyptian goddess with an interest in the Celtic Revival; both claimed that their priestly lineages derived directly from the Egyptian queen Scota, mythical foundress of Ireland and Scotland; and both groups used dramatic ritual and theatrical events as avenues for the promulgation of their Isis cults. The Parisian Isis movement and the Fellowship of Isis were (and are) historically-inaccurate syncretic constructions that utilised the tradition of an Egyptian origin of the peoples of Scotland and Ireland to legitimise their founders’ claims of lineal descent from an ancient Egyptian priesthood. To explore this contention, this chapter begins with brief overviews of Isis in antiquity, her later appeal for Enlightenment Freemasons, and her subsequent adoption by the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. It then explores the Parisian cult of Isis, its relationship to the Celtic Revival, the myth of the Egyptian queen Scota, and examines the establishment of the Fellowship of Isis. The Parisian mysteries of Isis and the Fellowship of Isis have largely been overlooked by critical scholarship to date; the use of the medieval myth of Scota by the founders of these groups has hitherto been left unexplored. -

The Founding of Ireland and Scotland

HOW IRELAND AND SCOTLAND WAS SETTLED A Jewish tribe left Egypt and settled in Ireland. They were called the Milesians and were the ruling class of Ireland. They evidently moved into Scotland and the throne of Ireland was moved under the reign of King Fergus. The Scotland lived in the mountain area of Scotland and were called the Scots. This article will proof that the Scotish people were a tribe of the Jews and they held the sceptre. The Jewish in Palestine did not have the sceptre after the captivity of Judah 500 B.C. Brief history of Ancient Ireland 1709 B.C. -The Parthalonnians are credited for being the first settlers of Ireland. The Parthalonians, whoever they may have been, ruled Ireland intermittently until 1709 BCE, when a tragedy befell them at the hands of Phoenician Formorians. 1492 B.C. – Nemedians were the Fir Bolgs. The island was then invaded by Nemedians from Scythia who lived in Ireland. The Nemedians were ruled by the Formorians for much of this period. A portion of the Nemedians escaped during their sojourn in the land and returned in 1492 BC as the Fir- Bolgs. The FirBlogs were later given as a place of settlement the Aran Islands under a King named Aengus. Formanians settled on another island. 1456 B.C -.DAN IN NORTH IRELAND Tuatha De Danaan settled Northern Ireland. The immigration of Dan to Ireland came in waves. A contingent of the famous Tuatha de Danaan (“Tribe of Dan”) arrived in Ireland 1456 B.C. and ruled for 440 years until 1016 BCE. -

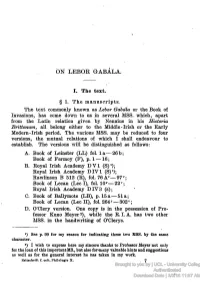

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. the Text

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. The text. § 1. The manuscripts. The text commonly known as Lebor Gabala or the Book of Invasions, has come down to us in several MSS. which, apart from the Latin relation given by Nennius in his Historia Brittomim, all belong either to the Middle-Irish or the Early Modern-Irish period. The various MSS. may be reduced to four versions, the mutual relations of which I shall endeavour to establish. The versions will be distinguished as follows: A. Book of Leinster (LL) fol. la—26b; Book of Fermoy (F), p. 1 —16; B. Royal Irish Academy DVI (S)1); Royal Irish Academy DIV1 (S)1); Rawlinson B 512 (R), fol. 76 Av— 97v; Book of Lecan (Lee I), fol. 10r—22v; Royal Irish Academy DIV3 (s); C. Book of Ballymote (LB), p. 15a—51 a; Book of Lecan (Lee H), fol. 264r—302v; D. OOlery version. One copy is in the possession of Pro- fessor Kuno Meyer2), while the R.I. A. has two other MSS. in the handwriting of O'Clerys. *) See p. 99 for my reason for indicating these two MSS. by the same character. 2) I wish to express here my sincere thanks to Professor Meyer not only for the loan of this important MS., but also formany valuable hints and suggestions as well as for the general interest he has taken in my work. Zeitschrift f. celt. Philologie X. 7 Brought to you by | UCL - University College London Authenticated Download Date | 3/3/16 11:57 AM OS A. G. VAN HAMEL, § 2. -

Genre and Identity in British and Irish National Histories, 1541-1691

“NO ROOM IN HISTORY”: GENRE AND IDENTIY IN BRITISH AND IRISH NATIONAL HISTORIES, 1541-1691 A dissertation presented by Sarah Elizabeth Connell to The Department of English In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of English Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts April 2014 1 “NO ROOM IN HISTORY”: GENRE AND IDENTIY IN BRITISH AND IRISH NATIONAL HISTORIES, 1541-1691 by Sarah Elizabeth Connell ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University April 2014 2 ABSTRACT In this project, I build on the scholarship that has challenged the historiographic revolution model to question the valorization of the early modern humanist narrative history’s sophistication and historiographic advancement in direct relation to its concerted efforts to shed the purportedly pious, credulous, and naïve materials and methods of medieval history. As I demonstrate, the methodologies available to early modern historians, many of which were developed by medieval chroniclers, were extraordinary flexible, able to meet a large number of scholarly and political needs. I argue that many early modern historians worked with medieval texts and genres not because they had yet to learn more sophisticated models for representing the past, but rather because one of the most effective ways that these writers dealt with the political and religious exigencies of their times was by adapting the practices, genres, and materials of medieval history. I demonstrate that the early modern national history was capable of supporting multiple genres and reading modes; in fact, many of these histories reflect their authors’ conviction that authentic past narratives required genres with varying levels of facticity. -

1 Ireland's Four Cycles of Myth and Legend Irish Mythology Has Been

Ireland's Four Cycles of Myth and Legend u u Irish mythology has been classified or taxonomized into four cycles (collections, sets) • From the oldest tales to the most recent, they are: the Mythological Cycle; the Ulster (or Red Branch) Cycle; the Fenian (or Ossianic) Cycle; and the Historical (or Kings') Cycle u u The Mythological Cycle is dominated by origin myths called pseudohistories • These tales narrate a series of foreign invasions of Ireland, with each new wave of invader-settlers marginalizing the formerly dominant group u The oldest group, the Fomorians, resemble the Greek Titans: semi-divine beings associated with the chaos that preceded the civilizing gods u The penultimate aggressor group, the Tuatha Dé Danann (people of the goddess Danu), suffered defeat at the hands of the Milesians or Gaels, who entered Ireland from northern Spain • Legendarily, some surviving members of the Tuatha Dé Danann became the fairies or "little people," occupying aerial or subterranean (underground) zones on the island of Ireland but with a different temporality • The Irish author C.S. Lewis uses this idea in his Narnia series, where the portal into Narnia—a place outside "regular' time—is a wardrobe u Might the Milesians have, in fact, come from Spain? • A March 2000 article in the esteemed science journal Nature revealed that 98% of Connacht (west-of-Ireland) men and 89% of Basque (northeast-of- Spain) men carry the ancestral (or hunter-gatherer) European DNA signature, which passes from father to son • By contrast with the high Irish and -

Ireland and the Old Testament Revision

Ireland and the Old Testament: Transmission, Translation, and Unexpected Influence 1. Introduction A medieval poem, attributed to the eleventh century poet Mael Ísu Ó’Brolcán, begins as follows: How good to hear your voice again Old love, no longer young, but true As when in Ulster I grew up And we were bedmates, I and you When first they put us twain to bed My love who speaks the tongue of heaven I was a boy with no bad thoughts A modest youth, and barely seven.1 1 Frank O’Connor, “A Priest Rediscovers His Psalm-Book,” in Kings, Lords, and Commons (London: Macmillan, 1961): 12. 1 While at first blush this sounds like a romantic ballad, this medieval work is in fact an ode to a long-lost psalm-book rediscovered by a cleric later in life.2 This lost love which “speaks the tongue of heaven” will be to many an unexpected object of affection in this verse; not only is it surprising that the Bible – and the Old Testament in particular – shows up in poetry of this sort, but that it does so in the hands of a medieval Irish priest runs counter to much popular opinion. If at all, contemporary readers might expect the Gospels to appear here, not least because of the influence of medieval works such as the Book of Kells, and their place in the contemporary landscape of Ireland and Irish tourism.3 Nevertheless, this poem highlights Ireland’s long, rich, and varied history of engagement with the Old Testament, a history that sometimes confirms our preconceptions, while at other times surprising us and confounding our expectations, as with our medieval priest and his unexpected object of affection. -

Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race by Thomas William Rolleston

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race by Thomas William Rolleston This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race Author: Thomas William Rolleston Release Date: October 16, 2010 [Ebook 34081] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MYTHS AND LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE*** MYTHS & LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE Queen Maev T. W. ROLLESTON MYTHS & LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE CONSTABLE - LONDON [8] British edition published by Constable and Company Limited, London First published 1911 by George G. Harrap & Co., London [9] PREFACE The Past may be forgotten, but it never dies. The elements which in the most remote times have entered into a nation's composition endure through all its history, and help to mould that history, and to stamp the character and genius of the people. The examination, therefore, of these elements, and the recognition, as far as possible, of the part they have actually contributed to the warp and weft of a nation's life, must be a matter of no small interest and importance to those who realise that the present is the child of the past, and the future of the present; who will not regard themselves, their kinsfolk, and their fellow-citizens as mere transitory phantoms, hurrying from darkness into darkness, but who know that, in them, a vast historic stream of national life is passing from its distant and mysterious origin towards a future which is largely conditioned by all the past wanderings of that human stream, but which is also, in no small degree, what they, by their courage, their patriotism, their knowledge, and their understanding, choose to make it. -

The True Roots and Origin of the Scots

THE TRUE ROOTS AND ORIGIN OF THE SCOTS A RESEARCH SUMMARY AND POINTERS TOWARD FURTHER RESEARCH “Wherever the pilgrim turns his feet, he finds Scotsmen in the forefront of civilization and letters. They are the premiers in every colony, professors in every university, teachers, editors, lawyers, engineers and merchants – everything, and always at the front.” – English writer Sir Walter Besant Copyright © C White 2003 Version 2.1 This is the first in a series of discussion papers and notes on the identity of each of the tribes of Israel today Some Notes on the True Roots and Origin of the Scots TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory Remarks 3 Ancient Judah 6 Migrations of Judah 17 British Royal Throne 25 National and Tribal Emblems 39 Scottish Character and Attributes 44 Future of the Scots – Judah’s Union with the rest of Israel 55 Concluding Remarks 62 Bibliography 65 “The mystery of Keltic thought has been the despair of generations of philosophers and aesthetes … He who approaches it must, I feel, not alone be of the ancient stock … but he must also have heard since childhood the deep and repeated call of ancestral voices urging him to the task of the exploration of the mysteries of his people … He is like a man with a chest of treasure who has lost the key” (The Mysteries of Britain by L Spence) 2 Some Notes on the True Roots and Origin of the Scots INTRODUCTORY REMARKS Who really are the Scottish peoples? What is their origin? Do tradition, national characteristics and emblems assist? Why are they such great leaders, administrators and inventors? Is there a connection between them and the ancient Biblical tribe of Judah? Why did the British Empire succeed when other Empires did not? Was it a blessing in fulfillment of prophecies such as that in Gen 12:3? Why were the Scots so influential in the Empire, way beyond their population numbers? Today book after book; article after article; universities, politicians, social workers spread lies about the British Empire, denigrating it. -

Ancient Irish Rhetoric

Rhetoric of Myth, Magic, and Conversion: Ancient Irish Rhetoric Of our conflicts with others we make rhetoric; of our conflicts with ourselves we make poetry—William Butler Yeats Our first tendency is to look outside Europe when searching for ancient rhetorics that do not follow the Greco-Roman tradition. After all, much of European culture was strongly influenced by Roman culture, especially following the conquests of Julius Caesar in 58-51 BCE and subsequent conquests that brought most of Europe under Roman control. Rome’s civic practices, including variations of Greco-Roman rhetoric, were eventually taught in most parts of the continent. Even after the fall of the Roman Empire in 476 A.D., Greco-Roman rhetoric continued to flourish in Europe, because St. Augustine, a generation earlier, had re-purposed it for the Roman Catholic Church in his On Christian Doctrine (426 A.D.). Ireland, however, offers us an interesting exception to Romanized Europe. The island’s remoteness allowed it to preserve much of its Celtic culture while keeping at arm’s length the cultural influences of Rome and much of medieval Europe. The Irish traded with the Roman world, and eventually they were converted to Christianity after the arrival of St. Patrick in 431 AD. Nevertheless, Irish culture stood apart from European culture, especially during the crucial period of the so-called “Dark Ages” from the fifth to ninth centuries. It was not until the date 1172 AD, when England’s Henry II conquered Ireland, that we might mark Ireland’s capitulation to European civic and educational practices—and then only as a conquered people. -

Early Races According to Irish Bards. Our Nationalities James Bonwick the Ancient Irish Literature Is of Far Greater Interest, P

Early Races According To Irish Bards. Our nationalities James Bonwick 1880 • The ancient Irish literature is of far greater interest, perhaps, than that of Great Britain, France, Spain, or Germany. Most nations traced their origin to the gods at first. Afterwards, when the deities rose somewhat higher than the earth, and retreated to the sacred precincts of a celestial Olympus, men were content with a fatherhood of the loftiest heroic character. Homer’s grand poem furnished a Trojan parentage for several races. The Irish narrations are different. Though notices of men and events of a strictly Pagan character are not unknown, the only really definite conceptions of the chroniclers, Bards and Monks, were connected with Scriptural names and saints. This fact gives us a distinct clue to the age of the stories, which must have been after the conversion to Christianity. We are told by Irish Bards of seven distinct invasions. The Firbolgs, Tuath de Danaans, and Milesians seem the only ones securing permanent occupation. A number of tribes may be indicated, with no special account of their history. The Lettmanni or Leathmannice are said to have given name to the Avene Liff or Liffey ; some trace the tribe to Livonia of the Baltic. The Mantinei might have been Teutons of Zealand. The Veneti were, also, in Venice. The Damnonians or Domnann are called the aborigines of Connaught, and thought to be Belgæ’. The Galians gave name to Ulster in Irish ; others style them Gallenians,andsaytheycame from Britain under Slangy, first monarch of Ireland. But they were not the earliest coiners, being considered the third colony.