UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Study of the Divorce of Mohammad Reza Shah with Soraya Bakhtiari

WALIA journal 30(1): 128-130, 2014 Available online at www.Waliaj.com ISSN 1026-3861 © 2014 WALIA Study of the divorce of Mohammad Reza Shah with Soraya Bakhtiari Hatam Mosaei *, Danesh Abasi Shehni, Hasan Mozafari Babadi, Saeed Bahari Babadi Department of History, Shoushtar Branch, Islamic Azad University, Shoushtar Branch, Iran Abstract: One of the key factors that led to the separation of Soraya, Mohammad Reza Shah was of another. Soraya inability to get pregnant and give birth to a succession of Crown Prince Mohammad Reza, Pahlavi series to the throne hereditary monarchy to maintain. The great rivalries of the 23 Persian date March 14, 1958 we were separated. Key words: Soraya Bakhtiari; Mohammad Reza Shah 1. Introduction December 1954 Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi and Soraya launched a three-month trip to America and * After August 28 at 1953 coup and overthrow Europe, Advisors and specialists in a hospital in New Mosaddegh. Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi was able York who had infertility, Soraya was examined, after to restore the absolute monarchy, After a while the numerous experiments and concluded, and Soraya is King and Queen Soraya decided to travel to America the problem of infertility, After some rest and leisure and Europe, Work has already begun planning the and to avoid apprehension and concern in recent ambush had happened, but his work ,In the years will be charged. Some believe that the visit of November 1954. Shah poor Ali Reza only brother the Shah and Soraya in Boston Services Shah Reza. According to the constitution and the gynecological consultation with the physicians mother of his brother Shah Qajar. -

Protests Held in Iran Against Saudi Arabia

INTERNATIONAL SATURDAY, JANUARY 9, 2016 Two refugees arrested in US over IS links LOS ANGELES: US authorities said two peo- affiliate Ansar al-Islam (Partisans of Islam), citizenship or naturalization unlawfully and From Refugee to Radical ple with ties to the Islamic State group were which previously operated under its own making false statements. Hardan, who lives in Houston, was due in court yesterday in California and banner in Iraq and Syria. Listed as a terrorist Texas Governor Greg Abbott and other granted legal permanent resident status Texas, including a refugee from Syria organization by the United Nations and the local officials said Hardan’s arrest backed in 2011, two years after entering the accused of returning there to fight alongside US, its Iraqi faction has since merged with their calls for a refugee ban. “This is precisely United States. According to the indict- IS. The arrests come amid heightened securi- the Islamic State group, though some of its why I called for a halt to refugees entering ment, he provided training, expert advice ty in the United States following last month’s Syrian fighters rejected IS. US Attorney the US from countries substantially con- and assistance to IS. He also lied on his assault by a radicalized Muslim couple in Benjamin Wagner was careful to stress that trolled by terrorists,” he said. The state’s formal application to become a natural- California that left 14 people dead and the “while (Jayab) represented a potential safety Attorney General Ken Paxton called the ized US citizen, saying he was not associa- November terror attacks in Paris. -

Iranian Espionage in the United States and the Anti-SAVAK Campaign (1970-1979)

The Shah’s “Fatherly Eye” Iranian Espionage in the United States and the Anti-SAVAK Campaign (1970-1979) Eitan Meisels Undergraduate Senior Thesis Department of History Columbia University 13 April 2020 Thesis Instructor: Elisheva Carlebach Second Reader: Paul Chamberlin Meisels 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Historiography, Sources, and Methods ......................................................................................... 12 Chapter 1: Roots of the Anti-SAVAK Campaign ......................................................................... 14 Domestic Unrest in Iran ............................................................................................................ 14 What Did SAVAK Aim to Accomplish? .................................................................................. 19 Chapter 2: The First Phase of the Anti-SAVAK Campaign (1970-1974) .................................... 21 Federal Suspicions Stir ............................................................................................................. 21 Counterintelligence to Campaign ............................................................................................. 24 Chapter 3: The Anti-SAVAK Campaign Expands (1975-1976) ................................................. -

The Historical Relationship Between Women's Education and Women's

The Historical Relationship between Women’s Education and Women’s Activism in Iran Somayyeh Mottaghi The University of York, UK Abstract This paper focuses on the historical relationship between women’s education and women’s activism in Iran. The available literature shows that education is consid- ered to be one important factor for Iranian women’s activism. The historical anal- ysis of women’s demand for education helps us to gain an understanding of the past in order to relate it to the future. This paper analyzes Iranian women’s active participation in education throughout the Safavid period (1501-1722) and the Qajar period (1794-1925). Women’s demand for education continued into the twentieth century and by the time of the constitutional revolution (1905-1911), during which Iranian women participated immensely in political affairs, the alliance of elite and non-elite women was clearly visible around educational issues. Women’s demand for education gained particular visibility; however, the focus shifted from modernization based on Westernization during the Pahlavi period (1925-1979), towards Islamization from 1979 onwards. This paper analyzes the ways in which, during different eras, women have been treated differently regard- ing their rights to education and at some points they faced difficulties even in exercising them; therefore, they had to constantly express their demands. Key words Iran, Education, Women’s movement, Historical perspective Introduction The historical analysis of women’s activism in Iran shows that educa- tion has always been considered an important factor for Iranian women and something that they have always demanded. The right to education is non-negotiable, embedded in the teaching of Islam as well as in hu- ㅣ4 ❙ Somayyeh Mottaghi man rights provisions. -

Unveiling America: the Popularization of Iranian Exilic Memoirs in Post 9/11 American Society

Khorsand 1 Unveiling America: The Popularization of Iranian Exilic Memoirs In Post 9/11 American Society By Anahita Khorsand Department: English Thesis Advisor: Karim Mattar, English Honors Council Representative: Karen Jacobs, English Third Reader: Joseph Jupille, Political Science Fourth Reader: Mark Winokur, English Defense Date: April 1, 2019 Khorsand 2 Table of Contents Introduction: Iranian History In Multiple Dimensions……………………………………3 Chapter 1: America’s Expanding Society………………………………………………..16 Chapter 2: Reading Lolita Under Attack………………………………………………...36 Chapter 3: The Complete Persepolis: Picturing Identity………………………………...57 Conclusion: Instigating Cultural Growth………………………………………………...78 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………..83 Khorsand 3 Introduction: Iranian History in Multiple Dimensions With the growing political tensions between the powers of the West and those of the Middle East, the representative voices of these respective regions ameliorate a cross- cultural understanding of human experience. The contemporary appeal of Middle Eastern literature for Western and exilic audiences affirm a personal connection to themes of identity conflict and self-reflection among global society. Anglophone Iranian works, in particular, rose in popularity among American readers in the early 2000s and continue their prevalence among book clubs across the nation. As the daughter of two Iranian immigrants, I can infer from my own fascination how Iranian literature arose. However, the increasingly hostile rhetoric surrounding Iran in the -

Notes and Documents - United Nations Centre Against Apartheid, No

Notes and Documents - United Nations Centre Against Apartheid, No. 8/70 http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.nuun1970_06 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Notes and Documents - United Nations Centre Against Apartheid, No. 8/70 Alternative title Notes and Documents - United Nations Centre Against ApartheidNo. 8/70 Author/Creator United Nations Centre against Apartheid Publisher Department of Political and Security Council Affairs Date 1970-04-00 Resource type Reports Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa, Sweden, Iran, Islamic Republic of, Somalia Coverage (temporal) 1970 Source Northwestern University Libraries Description Address by the Secretary-General, U Thant; Address by Princess Ashraf Pahlavi (Iran), Chairman of the Commission on Human Rights Address by Mr. -

One Revolution Or Two? the Iranian Revolution and the Islamic Republic

ONE REVOLUTION OR TWO? THE IRANIAN REVOLUTION AND THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC By Val Moghadam Introduction The bicentennial of the French Revolution happens to coincide with the tenth anniversary of the Iranian Revolution. While the first has been widely regarded as the quintessential social and transformative revolution, the sec- ond is problematical both theoretically and politically. Whereas the October Revolution was in many ways the vanguard revolution par excellence, the Iranian Revolution appears retrograde. In the Marxist view, revolution is an essential part of the forward march of history, a progressive step creating new social-productive relations as well as a new political system, consciousness and values. In this context, how might events in Iran be termed 'revolutionary'? Precisely what kind of a revolution transpired between 1977 and 1979 (and afterward)? Surely clerical rule cannot be regarded as progressive? In what sense, then, can we regard the Iranian Revolution as a step forward in the struggle for emancipation of the Iranian working classes? Clearly the Iranian Revolution presents itself as an anomaly. The major revolutions that have been observed and theorized are catego- rized by Marxists as bourgeois or socialist revolutions.1 This is determined by the revolution's ideology, leadership, programme, class base and orientation, and by changes in the social structure following the change of regime. Fur- ther, there is a relationship between modernity and revolution, as discussed by Marx and Engels in The Communist Manifesto, suggested by Marshall Berman in his engaging All That Is Solid Melts Into Air, and elaborated by Perry Anderson in a recent essay .2 Some academic theorists of revolution and social change (Banington Moore, Theda Skocpol, Charles Tilly, Ellen Kay Trimberger, Susan Eckstein, taking their cue from Marx) have stressed the modernizing role played by revolutions. -

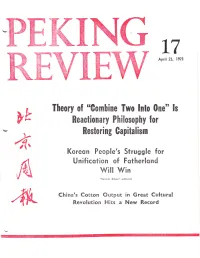

Peking Review, No.' 17

ffffi L7 April 23, l97l n'Gombine Theory 0f Two lnto 0lre" ls eh Reaetionary Phllosophy for Restoring Capitalism 4" Koreon People's Stnuggle for Unificction of Fstherlond wil! \Min {e "Renmin Riboo" editoriol China's Cotton Output in Great Cultural ,W Revolution Hits a New Record Y/ 0uotalioms From te,nin Marx's philosophy is a consummare phi- losophical matetiaLism which has provided mankind, 'and es,pecially the working class, with powerful instruments of knowledge. fa:D Y-, The splitting of a sir"gle whole and the.cog- :' nition' of its, contradictory part$ is the, e $sence : of dialectics. v- E"ffiE WEEK Cqmbodion New Yeor's Doy Congress Kuo Mo-jo'met the distin- the Chinese people har,'e always fol- Bonquet guished Iranian guests the same day. lowed '"vith interest and attention the Premier Chou gave a banquet in franian people's efforts in their Samdech Norodom Sihanouk, Head their honour the same evening. s'rruggle against foreign aggression of State of Cambodia, and Madame and for national construction. In At the banquet Premier Chou and Sihanouk gaYe a banquet on April order to safeguard state sovereignty Frincess Ashraf proposed toasts to 13 in honour of Chinese leaders on and proteet their national resouices, the growing friendship betrveen the the oceasion of. Cambodia's New Iran. together with other members of people of China and Iran. Premier Year's Day. Present at the banquet the Organization of Petroleum Ex- Chou proposed a toast to the health were Premier Chou En-lai, Chief of porting Countries, have reeently of His MajesW Mohammad Reza the P.L.A. -

Celebrating Diversity ... • BUILDING THE

138 March - April 2012 Vol. XXIII No. 138 • Celebrating Diversity ... • BUILDING THE DREAM Design: Saeed Jalali • FinDing my groove • the Poetry oF bijan jalali • Homework BreaktHrougH • PAssING THE ToRcH of sUccEss rocks san Diego • art of iran in tHe eigHteentH anD nineteentH centuries: Qajar era BaHa’is of iran: A sToRy of sTRUGGLE No. 138/ March - April 2012 1 138 Editorial Since 1991 By: Shahri Estakhry Persian Cultural Center’s Celebrating Diversity – bilingual magazine is a bi-monthly publication organized for Learning To Respect Differences literary, cultural and information purposes Financial support is provided by the City of Once again, it is time for the jubilation of Norouz. Time to say farewell to the dormancy of San Diego Commission for Arts and Culture. another winter season and welcome the rejuvenation of our Mother Earth with the coming of Persian Cultural Center spring. We should get ready to dance with the blossoming of every flower and be thankful to have 9265 Dowdy Dr. # 105 • san Diego, CA 92126 been given another spring to celebrate and enjoy the blessing of being alive. tel :( 858) 653-0336 fax & message: (619) 374-7335 As I write this editorial it is the beginning of the Chinese New Year, the year of the Dragon. Less email: [email protected] web site: www.pccus.org than a month ago we celebrated the coming of 2012 in the Gregorian calendar. Now coming up www.pccsd.org on the first day of spring will be the Norouz celebration, representing a new year for nearly 300 million people around the world. -

Hhadi Dawi, Members Months

-- ' - 1 Pm ,- H H : :M k : i MES A.) 1 V,' Choootal : 5P' ,.. 7 f . PRICE Af. 3 ' SUNDAY, OCTOBER' 16, 1966, (MIZAN 24, 1345, S.H.) VOL. V, NO. 168. f ;TZ KABUL, Nation Celebrates Monarch's Birthday Princess Ashraf Returns Home Delkusha deception, Buzkashi Mark Fete Her Royal Highness Princess Ashraf Pehlavi, here for a three day visit at the invitation of HRH Princess Bllqls, left for home this morning. She was seen off at the airport by Princess Bilqis, : : "Jr. Sardar Abdul Wall. Nour Ahmad Etemadi, the acting Prime Min- ; ister and Minister of Foreign Af- fairs, the Minister of Court cabi- r net members, the Mayor of Kabul, the Governor of Kabul, Ambas- OVi sador and members of the Iran- J ian Embassy. The two Princesses inspected a guard of honour. An album of photos depicting scenes of Prin- - w h , "".!"- J- 1 4 cess Ashraf's visit to Afghanistan, tr J was presented to her. t sis- Princess Ashraf Pahlavi, . His Royal High Ahmad Shah, High President of the ? Prince '4 ter of the Shah of Iran, last night Afghan Red Crescent Society delivering a message to the nation 1 ' had dinner with His Majesty the over Radio Afghanistan on the occasion of the Red Crescent King and Her Majesty the Queen ' V in Gulkhana Palace. Week. '..v.', ".h HRH - Ahmad Shah and his HRH Prince Ahmad Shah Praises wife Princess Khatol, HRH Prin- cess Bilqis and her husband, Work Of Red Crescent Society Sardar Abdul Wali other mem- : The following is On this occasion J would like to bers of royal family, Editor's note the Nour speech His Royal express my satisfaction to my col-- Ahmad Etemadi, Acting the text of the of Prime Highness Prince Ahmad Shah broad leagues. -

Complete Dissertation

VU Research Portal Next Generation Diaspora: the formation of Iranian American-ness among second- generation migrant internet users in Los Angeles Alinejad, D. 2015 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Alinejad, D. (2015). Next Generation Diaspora: the formation of Iranian American-ness among second- generation migrant internet users in Los Angeles. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 03. Oct. 2021 VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT Next Generation Diaspora: the formation of Iranian American-ness among second-generation migrant internet users in Los Angeles ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. F.A. van der Duyn Schouten, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van de promotiecommissie van de Faculteit der Sociale Wetenschappen op maandag 16 februari 2015 om 13.45 uur in de aula van de universiteit, De Boelelaan 1105 door Donya Alinejad geboren te Teheran, Iran i promotoren: prof.dr. -

Shahr-E Now, Tehran's Red-Light District (1909–1979)

SHAHR-E NOW, TEHRAN’S RED-LIGHT DISTRICT (1909–1979): THE STATE, “THE PROSTITUTE,” THE SOLDIER, AND THE FEMINIST By Samin Rashidbeigi Submitted to Central European University Department of Gender Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of European Master in Women’s and Gender History Supervisor: Professor Francisca de Haan CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2015 Abstract This thesis deals with the history of Shahr-e Now, Tehran’s red-light district from 1909 until the 1979 Islamic Revolution. The district, as large as two football pitches, functioned as a sex market for almost seventy years with around 1,500 prostitutes living and working there. Shahr-e Now’s existence as “Tehran’s red-light district before the 1979 Revolution” has been only briefly mentioned in a number of scholarly works; however, the district has not been analyzed as a gendered and politically relevant urban construction in the context of modern Iranian history. This thesis uses the archival documents collected from The National Archive of Iran and The Document Center of Iran’s Parliament to explain Shahr-e Now’s long-lasting functioning in front of the public eye—despite the fundamental tension with Islamic morale. This thesis argues, firstly, that Shahr-e Now was initiated by state officials, and preserved during the Pahlavi period (1925–1979), mainly for the sake of the military population in Tehran. Using the vast literature on the rise of the modern army in Iran as part of the Pahlavi Dynasty’s establishment, this thesis explains that the increasing number of soldiers in Tehran was the main reason why the Pahlavi regime enabled/allowed the creation of Shahr-e Now; the state-regulated prostitution in Shahr-e Now served to provide the military with “clean women.” Moreover, this thesis suggests that the system of regulation within SN was pretty much similar to systems of regulation enforced by other modern(izing) nation states in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.