The Progress of Good Governance in Botswana 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Combined Seventeenth to Twenty-Second Periodic Reports Submitted by Botswana Under Article 9 of the Convention, Due Since 2009*

United Nations CERD/C/BWA/17-22 International Convention on Distr.: General 21 July 2020 the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination Original: English English, French and Spanish only Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination Combined seventeenth to twenty-second periodic reports submitted by Botswana under article 9 of the Convention, due since 2009* [Date received: 30 January 2020] * The present document is being issued without formal editing. GE.20-09810(E) CERD/C/BWA/17-22 General Information Replies to the list of issues prior to reporting CERD/C/BWA/QPR/17-22 Reply to paragraph 1 of the list of issues 1. In Botswana, the primary legislation that offers protection to human rights covered by the Convention is the Constitution. Section 3 of the Constitution accords fundamental rights and freedoms to every person on a non-discriminatory basis, including race. In addition, Section 15 of the Constitution specifically prohibits discrimination on the basis of, among others, race. 2. Since Botswana’s last report, significant legislative developments which promote and protect human rights covered by this Convention have taken place. These include the enactment of the Local Government Act of 2008, Cybercrime and Computer Related Crimes Act of 2018 and the Children’s Act of 2009. These laws incorporate the principle of non-discrimination on the basis of race in public procurement, transmission of electronic material and administration of the Children’s Act, respectively. 3. In terms of institutional framework, the Government has established a Human Rights Unit within the Ministry of Presidential Affairs, Governance and Public Administration. -

Botswana Guardian August 7, 2020 1

Botswana Guardian www.botswanaguardian.co.bw August 7, 2020 www.botswanaguardian.co.bw 1 Est. 1982 Fearless and Responsible ISSUE 4: Friday 7 AUGUST 2020 Alcohol industry jobs on the line p8 Botswana will send peace BDP in sixes troops on a and sevens need-to basis Ernest Moloi BG reporter Nicholas Mokwena Botswana will deploy troops BG reporter in peacekeeping missions only when there is “absolutely certain ember of positivity” that such effort will result Parliament in the promotion of a settlement, Mfor Jwaneng- President Dr. Mokgwetsi Masisi Mabutsane Mephato has said. Reatile has put his Masisi who is the incoming Chair party - Botswana of the SADC Organ on Defense, Democratic Party Politics and Security Cooperation (BDP) - in an told the media Wednesday evening awkward position. at State House 1 Gardens after a virtual Summit of the Organ Troika This follows his BDP MPs losing trust in Reatile plus Force Intervention Brigade- decision last week Troops Contributing Countries ‘VP and other senior party MPs not to vote with his (FIB-TCC) and the Democratic supported the motion so expectation colleagues for the Republic of Congo (DRC). was that Reatile will vote with us’ suspension Flanked by ministers Unity Dow I am a BDP member in good standing- SEE PAGE 6 and Kabo Morwaeng of Foreign Reatile SEE PAGE 5 LECHA LOAN #Areyeng BSB BotswanaBotswana Guardian Guardian 22 BGBGMARKETS MARKEts www.botswanaguardian.co.bw www.botswanaguardian.co.bw AugustAugust 7, 7, 2020 2020 Sefalana pays shareholders AbsaBotswana Guardian 2BG BGreporterMARKETS company annual financial statements. www.botswanaguardian.co.bw The divi- July 17, 2020 dend will be paid around the 25 th of August 200 appoint Sefalana group last week announced that the to shareholders registered by 14 th of the same board of directors ETFhas approved trading 27.5 thebe per up month. -

Daily Hansard 08 March 2017

DAILY YOUR VOICE IN PARLIAMENT THE SECOND MEETING OF THE THIRD SESSION OF THE ELEVENTH PARLIAMENT WEDNESDAY 08 MARCH 2017 MIXED VERSION HANSARD NO. 187 DISCLAIMER Unocial Hansard This transcript of Parliamentary proceedings is an unocial version of the Hansard and may contain inaccuracies. It is hereby published for general purposes only. The nal edited version of the Hansard will be published when available and can be obtained from the Assistant Clerk (Editorial). THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY SPEAKER The Hon. Gladys K. T. Kokorwe MP. DEPUTY SPEAKER The Hon. Kagiso P. Molatlhegi, MP Gaborone South Clerk of the National Assembly - Ms B. N. Dithapo Deputy Clerk of the National Assembly - Ms T. Tsiang Learned Parliamentary Counsel - Mr S. Chikanda Assistant Clerk (E) - Mr R. Josiah CABINET His Excellency Lt. Gen. Dr. S. K. I. Khama PH, FOM, - President DCO, DSM, MP. His Honour M. E. K. Masisi, MP. (Moshupa- Vice President Manyana) - Hon. Dr. P. Venson-Moitoi, MP. (Serowe South) - Minister of International Affairs and Cooperation Hon. S. Tsogwane, MP. (Boteti North) - Minister of Local Government and Rural Development Hon. N. E. Molefhi, MP. (Selebi Phikwe East) - Minister of Infrastructure and Housing Development Hon. S. Kgathi, MP. (Bobirwa) - Minister of Defence, Justice and Security Hon. O. K. Mokaila, MP. (Specially Elected) - Minister of Transport and Communications Hon. P. M. Maele, MP. (Lerala - Maunatlala) - Minister of Land Management, Water and Sanitation Services Hon. E. J. Batshu, MP. (Nkange) - Minister of Nationality, Immigration and Gender Affairs Hon. D. K. Makgato, MP. (Sefhare - Ramokgonami) - Minister of Health and Wellness Minister of Environment, Natural Resources Conservation and Hon. -

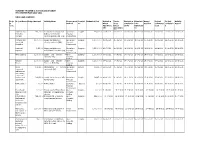

MINISTRY of DEFENCE JUSTICE and SECURITY PROCUREMEN PLAN 2021-2022 MDJS HEADQUARTERS Proje Ct Code Project Name Budget Amount Ac

MINISTRY OF DEFENCE JUSTICE AND SECURITY PROCUREMEN PLAN 2021-2022 MDJS HEADQUARTERS Proje Project Name Budget Amount Activity Name Procurement Descipli Estimated Cost Invitation Tender Evaluation Submissio Award Project Project Activity ct Method ne Direct Close completion n for Decision Commence Completio Report Code Appointme Direct by PE Adjudicati ment n ntte Appointme on ntte Uniforms and 143,230.00 A Contract for Supply and Quotations Supplies 143,230.00 20-04-2021 08-05-2021 08-04-2021 04-12-2021 15-06-2021 15-06-2021 22-06-2021 26-08-2021 Protective Delivery of Protective Proposal Clothing Clothing and Uniform (HQ) Procurement Domestic and 1,500,000.00 Supply and delivery of Quotations Supplies 1,500,000.00 16-08-2021 31-08-2021 31-08-2021 09-06-2021 15-06-2021 15-06-2021 22-06-2021 26-08-2021 household cleaning materials (HQ) Proposal Requisites Procurement Incidental 2,350,000 Supply and delivery of Quotations Supplies 2,350,000.00 16-07-2021 08-03-2021 08-05-2021 08-09-2021 08-12-2021 16-08-2021 20-08-2021 23-08-2021 Expenses Refreshments for MDJS (HQ) Proposal Procurement Office supplies 1,500,000.00 Supply and Delivery of Open Supplies 1,500,000.00 14-06-2021 07-09-2021 14-07-2021 23-07-2021 29-07-2021 08-02-2021 23-08-2021 27-08-2021 Sationery (HQ) Domestic Bidding Genuine 1,500,000.00 Supply and Delivery of Open Supplies 1,500,000.00 14-06-2021 07-09-2021 14-07-2021 23-07-2021 29-07-2021 08-02-2021 23-08-2021 27-08-2021 Toners Toners to MDJS HQ Domestic Bidding Office 172,110.00 Maintanance of running Quotations Service -

Tender Advert

TENDER ADVERT www.etender.co.bw Botswana Prison Service - DJS/MTC/PRI 031/2020/2021 Companies are invited to express their interest in the consultancy services on conditions of service for non-uniformed (civilian) staff of the Botswana Prison Service Closing: 21 January 2021 09H00 Site Visit: Contacts Senior Superintendent Ntshebe 3611711/21 3975398/003 [email protected] Senior Superintendent Bedi 3611711/21 3975398/003 [email protected] Collection : The physical address for the collection of Tender Document is Botswana Prison Service Headquarters, Broadhurst Industrial, Plot No. 10211, next to Mafulo House at the Supplies Office. Documents may be collected during office days between 07:30 and 12:45 and from 13:45 to 16:30 with effect from 14th December 2020. Queries relating to the issuance of these documents may be addressed to: Senior Superintendent Ntshebe and Senior Superintendent Bedi at Telephone No. 3611711/21, Fax Nos. 3975398/003, Email: [email protected] and [email protected] Fee: Delivery: The names and addresses of companies should be clearly marked on the envelope. One (1) original marked “Original” plus two (2) copies marked “Copy” must be hand-delivered in sealed envelopes. Identification details to be shown on each tender offer are: “Tender No. DJS/MTC/PRI 031/2020/2021 - Expression of Interest for Consultancy Services on Conditions of Service for Non-Uniformed (Civilian) Staff of the Botswana Prison Service”. Tender offers will be submitted to The Secretary, Ministerial Tender Committee, Ministry of Defence, Justice and Security Headquarters, Central Square Building, Ground Floor, Office No. 004 at the Tender Opening Hall, Gaborone, Central Business District, Phase 2, Plot No. -

Republic of Botswana - European Community

Republic of Botswana - European Community JOINT ANNUAL REPORT 2008 Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................... 3 1. Country Performance ..................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Update on the political situation and political governance ................................................................. 4 1.2 Update on the economic situation and economic governance............................................................. 6 1.3 Update on the poverty and social situation......................................................................................... 10 1.4 Update on the environmental situation............................................................................................... 12 2. Overview of past and ongoing co-operation................................................................................................. 13 2.1 Reporting on the financial performance of EDF resources............................................................... 13 2.2 Reporting on General and Sector Budget Support............................................................................ 14 2.3 Project and programmes in the focal and non-focal areas................................................................ 15 2.3.1 Focal Sector: Human Resource Development......................................................................... -

The Republic of Botswana Second and Third Report To

THE REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA SECOND AND THIRD REPORT TO THE AFRICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN AND PEOPLES' RIGHTS (ACHPR) IMPLEMENTATION OF THE AFRICAN CHARTER ON HUMAN AND PEOPLES’ RIGHTS 2015 1 | P a g e TABLE OF CONTENTS I. PART I. a. Abbreviations b. Introduction c. Methodology and Consultation Process II. PART II. A. General Information - B. Laws, policies and (institutional) mechanisms for human rights C. Follow-up to the 2010 Concluding observations D. Obstacles to the exercise and enjoyment of the rights and liberties enshrined in the African Charter: III. PART III A. Areas where Botswana has made significant progress in the realization of the rights and liberties enshrined in the African Charter a. Article 2, 3 and 19 (Non-discrimination and Equality) b. Article 7 & 26 (Fair trial, Independence of the Judiciary) c. Article 10 (Right to association) d. Article 14 (Property) e. Article 16 (Health) f. Article 17 (Education) g. Article 24 (Environment) B. Areas where some progress has been made by Botswana in the realization of the rights and liberties enshrined in the African Charter a. Article 1er (implementation of the provisions of the African Charter) b. Article 4 (Life and Integrity of the person) c. Article 5 (Human dignity/Torture) d. Article 9 (Freedom of Information) e. Article 11 (Freedom of Assembly) f. Article 12 (Freedom of movement) g. Article 13 (participation to public affairs) h. Article 15 (Work) i. Article 18 (Family) j. Article 20 (Right to existence) k. Article 21 (Right to freely dispose of wealth and natural resources) 2 | P a g e C. -

Judging the Epidemic: a Judicial Handbook on HIV, Human Rights

Judging the epidemic A judicial handbook on HIV, human rights and the law UNAIDS / JC2497E (English original, May 2013) ISBN 978-92-9253-025-9 Copyright © 2013. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). All rights reserved. Publications produced by UNAIDS can be obtained from the UNAIDS Information Production Unit. Reproduction of graphs, charts, maps and partial text is granted for educational, not-for-profit and commercial purposes as long as proper credit is granted to UNAIDS: UNAIDS + year. For photos, credit must appear as: UNAIDS/name of photographer + year. Reproduction permission or translation-related requests—whether for sale or for non-commercial distribution—should be addressed to the Information Production Unit by e-mail at: [email protected]. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNAIDS concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. UNAIDS does not warrant that the information published in this publication is complete and correct and shall not be liable for any damages incurred as a result of its use. Unless otherwise indicated photographs used in this document are used for illustrative purposes only. Unless indicated, any person depicted in the document is a “model”, and use of the photograph does not indicate endorsement by the model of the content of this document nor is there any relation between the model and any of the topics covered in this document. -

IN the HIGH COURT of BOTSWANA HELD at LOBATSE Misca. No. 52

IN THE HIGH COURT OF BOTSWANA HELD AT LOBATSE Misca. No. 52 of 2002 In the matter between: ROY SESANA 1st Applicant KEIWA SETLHOBOGWA AND OTHERS 2nd & further Applicants and THE ATTORNEY GENERAL (in his Respondent capacity as Recognized agent of the Government of the Republic of Botswana) Mr. G. Bennett for the Applicants Mr. S. T. Pilane with him Mr. L. D. Molodi for the Respondent J U D G M E N T CORAM: Hon. Mr. Justice M. Dibotelo Hon. Justice U. Dow Hon. Mr. Justice M. P. Phumaphi M. DIBOTELO, J.: 1. On the 19 February 2002, the Applicants filed an urgent application on notice of motion seeking at paragraphs 2 and 3 thereof an order declaring, inter alia, that: “2 (a) The termination by the Government with effect from 31 January 2002 of the following basic and essential services to the Applicants in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR) (namely) – i. the provision of drinking water on a weekly basis; ii. the maintenance of the supply of borehole water; iii. the provision of rations to registered destitutes; iv. the provision of rations for registered orphans; v. the provision of transport for the Applicants’ children to and from school; vi. the provision of healthcare to the Applicants through mobile clinics and ambulance services is unlawful and unconstitutional; 2. the Government is obliged to: (i) restore to the Applicants the basic and essential services that it terminated with effect from 31 January 2002; and (ii) continue to provide to the Applicants the basic and essential services that it had been providing to them immediately prior to the termination of the provision of these services; (c) those Applicants, whom the Government forcibly removed from the Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR) after the termination of the provision to them of the basic and essential services referred to above, have been unlawfully despoiled of their possession of the land which they lawfully occupied in their settlements in the CKGR, and should immediately be restored to their possession of that land. -

Land Tenure Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization

Land Tenure Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization. Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Ijagbemi, Bayo, 1963- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 17:13:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/196133 LAND TENURE REFORMS AND SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION IN BOTSWANA: IMPLICATIONS FOR URBANIZATION by Bayo Ijagbemi ____________________ Copyright © Bayo Ijagbemi 2006 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2006 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Bayo Ijagbemi entitled “Land Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization” and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr Thomas Park _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr Stephen Lansing _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr David Killick _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr Mamadou Baro Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

State of the Nation Address to the 3Rd Session of the 10Th Parliament

State of the Nation Address to the 3rd Session of the 10th Parliament 08/11/11 State of the Nation Address to the 3rd Session of the 10th Parliament State of the Nation Address to the 3rd Session of the 10th Parliament STATE OF THE NATION ADDRESS BY HIS EXCELLENCY Lt. GEN. SERETSE KHAMA IAN KHAMA PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA TO THE THIRD SESSION OF THE TENTH PARLIAMENT "BOTSWANA FIRST" 7th November 2011, GABORONE: 1. Madam Speaker, before we begin, I request that we all observe a moment of silence for those who have departed during the past year. Thank you. 2. Let me also take this opportunity to commend the Leader of the House, His Honour the Vice President, on his recent well deserved awards. In addition to the Naledi ya Botswana, which he received for his illustrious service to the nation, His Honour also did us proud when he received a World Citizen Award for his international, as well as domestic, contributions. I am sure other members will agree with me that these awards are deserving recognition of a true statesman. 3. Madam Speaker, it is a renewed privilege to address this Honourable House and the nation. This annual occasion allows us to step back and take a broader look at the critical challenges we face, along with the opportunities we can all embrace when we put the interests of our country first. 4. As I once more appear before you, I am mindful of the fact that this address will be the subject of further deliberations. -

Thursday 26 November 2020 the First Meeting of the Second Session of the Twelfth Parliament English Version

THE FIRST MEETING OF THE SECOND SESSION OF THE TWELFTH PARLIAMENT THURSDAY 26 NOVEMBER 2020 ENGLISH VERSION HANSARD NO: 200 THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY SPEAKER The Hon. Phandu T. C. Skelemani PH, MP. DEPUTY SPEAKER The Hon. Mabuse M. Pule, MP. (Mochudi East) Clerk of the National Assembly - Ms B. N. Dithapo Deputy Clerk of the National Assembly - Mr L. T. Gaolaolwe Learned Parliamentary Counsel - Ms M. Mokgosi Assistant Clerk (E) - Mr R. Josiah CABINET His Excellency Dr M. E. K. Masisi, MP. - President His Honour S. Tsogwane, MP. (Boteti West) - Vice President Minister for Presidential Affairs, Governance and Public Hon. K. N. S. Morwaeng, MP. (Molepolole South) - Administration Hon. K. T. Mmusi, MP. (Gabane-Mmankgodi) - Minister of Defence, Justice and Security Hon. Dr L. Kwape, MP. (Kanye South) - Minister of International Affairs and Cooperation Hon. E. M. Molale, MP. (Goodhope-Mabule ) - Minister of Local Government and Rural Development Hon. K. S. Gare, MP. (Moshupa-Manyana) - Minister of Agricultural Development and Food Security Minister of Environment, Natural Resources Conservation Hon. P. K. Kereng, MP. (Specially Elected) - and Tourism Hon. Dr E. G. Dikoloti MP. (Mmathethe-Molapowabojang) - Minister of Health and Wellness Hon. T.M. Segokgo, MP. (Tlokweng) - Minister of Transport and Communications Hon. K. Mzwinila, MP. (Specially Elected) - Minister of Land Management, Water and Sanitation Services Minister of Youth Empowerment, Sport and Culture Hon. T. M. Rakgare, MP. (Mogoditshane) - Development Hon. A. M. Mokgethi, MP. (Gaborone Bonnington North) - Minister of Nationality, Immigration and Gender Affairs Hon. Dr T. Matsheka, MP. (Lobatse) - Minister of Finance and Economic Development Hon. F. M. M.