Gender Equality and Women's Empowerment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Textual and Visual Uses of the Literary Motif of Cross-Dressing In

The Textual and Visual Uses of the Literary Motif of Cross-Dressing in Medieval French Literature, 1200–1500 Vanessa Elizabeth Wright Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of PhD in Medieval Studies University of Leeds Institute for Medieval Studies September 2019 2 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Vanessa Elizabeth Wright to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisors Rosalind Brown-Grant, Catherine Batt, and Melanie Brunner for their guidance, support, and for continually encouraging me to push my ideas further. They have been a wonderful team of supervisors and it has been a pleasure to work with them over the past four years. I would like to thank my examiners Emma Cayley and Helen Swift for their helpful comments and feedback on this thesis and for making my viva a positive and productive experience. I gratefully acknowledge the funding that allowed me to undertake this doctoral project. Without the School of History and the Institute for Medieval Studies Postgraduate Research Scholarship, I would not have been able to undertake this study. Trips to archives and academic conferences were made possible by additional bursaries and fellowships from Institute for Medieval Studies, the Royal Historical Society, the Society for the Study of Medieval Languages and Literatures, the Society for Medieval Feminist Scholarship’s Foremothers Fellowship (2018), and the Society for the Study of French History. -

The Marriage Issue

Association for Jewish Studies SPRING 2013 Center for Jewish History The Marriage Issue 15 West 16th Street The Latest: New York, NY 10011 William Kentridge: An Implicated Subject Cynthia Ozick’s Fiction Smolders, but not with Romance The Questionnaire: If you were to organize a graduate seminar around a single text, what would it be? Perspectives THE MAGAZINE OF THE ASSOCIATION FOR JEWISH STUDIES Table of Contents From the Editors 3 From the President 3 From the Executive Director 4 The Marriage Issue Jewish Marriage 6 Bluma Goldstein Between the Living and the Dead: Making Levirate Marriage Work 10 Dvora Weisberg Married Men 14 Judith Baskin ‘According to the Law of Moses and Israel’: Marriage from Social Institution to Legal Fact 16 Michael Satlow Reading Jewish Philosophy: What’s Marriage Got to Do with It? 18 Susan Shapiro One Jewish Woman, Two Husbands, Three Laws: The Making of Civil Marriage and Divorce in a Revolutionary Age 24 Lois Dubin Jewish Courtship and Marriage in 1920s Vienna 26 Marsha Rozenblit Marriage Equality: An American Jewish View 32 Joyce Antler The Playwright, the Starlight, and the Rabbi: A Love Triangle 35 Lila Corwin Berman The Hand that Rocks the Cradle: How the Gender of the Jewish Parent Influences Intermarriage 42 Keren McGinity Critiquing and Rethinking Kiddushin 44 Rachel Adler Kiddushin, Marriage, and Egalitarian Relationships: Making New Legal Meanings 46 Gail Labovitz Beyond the Sanctification of Subordination: Reclaiming Tradition and Equality in Jewish Marriage 50 Melanie Landau The Multifarious -

The Woman-Slave Analogy: Rhetorical Foundations in American

The Woman-Slave Analogy: Rhetorical Foundations in American Culture, 1830-1900 Ana Lucette Stevenson BComm (dist.), BA (HonsI) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2014 School of History, Philosophy, Religion and Classics I Abstract During the 1830s, Sarah Grimké, the abolitionist and women’s rights reformer from South Carolina, stated: “It was when my soul was deeply moved at the wrongs of the slave that I first perceived distinctly the subject condition of women.” This rhetorical comparison between women and slaves – the woman-slave analogy – emerged in Europe during the seventeenth century, but gained peculiar significance in the United States during the nineteenth century. This rhetoric was inspired by the Revolutionary Era language of liberty versus tyranny, and discourses of slavery gained prominence in the reform culture that was dominated by the American antislavery movement and shared among the sisterhood of reforms. The woman-slave analogy functioned on the idea that the position of women was no better – nor any freer – than slaves. It was used to critique the exclusion of women from a national body politic based on the concept that “all men are created equal.” From the 1830s onwards, this analogy came to permeate the rhetorical practices of social reformers, especially those involved in the antislavery, women’s rights, dress reform, suffrage and labour movements. Sarah’s sister, Angelina, asked: “Can you not see that women could do, and would do a hundred times more for the slave if she were not fettered?” My thesis explores manifestations of the woman-slave analogy through the themes of marriage, fashion, politics, labour, and sex. -

Botswana Guardian August 7, 2020 1

Botswana Guardian www.botswanaguardian.co.bw August 7, 2020 www.botswanaguardian.co.bw 1 Est. 1982 Fearless and Responsible ISSUE 4: Friday 7 AUGUST 2020 Alcohol industry jobs on the line p8 Botswana will send peace BDP in sixes troops on a and sevens need-to basis Ernest Moloi BG reporter Nicholas Mokwena Botswana will deploy troops BG reporter in peacekeeping missions only when there is “absolutely certain ember of positivity” that such effort will result Parliament in the promotion of a settlement, Mfor Jwaneng- President Dr. Mokgwetsi Masisi Mabutsane Mephato has said. Reatile has put his Masisi who is the incoming Chair party - Botswana of the SADC Organ on Defense, Democratic Party Politics and Security Cooperation (BDP) - in an told the media Wednesday evening awkward position. at State House 1 Gardens after a virtual Summit of the Organ Troika This follows his BDP MPs losing trust in Reatile plus Force Intervention Brigade- decision last week Troops Contributing Countries ‘VP and other senior party MPs not to vote with his (FIB-TCC) and the Democratic supported the motion so expectation colleagues for the Republic of Congo (DRC). was that Reatile will vote with us’ suspension Flanked by ministers Unity Dow I am a BDP member in good standing- SEE PAGE 6 and Kabo Morwaeng of Foreign Reatile SEE PAGE 5 LECHA LOAN #Areyeng BSB BotswanaBotswana Guardian Guardian 22 BGBGMARKETS MARKEts www.botswanaguardian.co.bw www.botswanaguardian.co.bw AugustAugust 7, 7, 2020 2020 Sefalana pays shareholders AbsaBotswana Guardian 2BG BGreporterMARKETS company annual financial statements. www.botswanaguardian.co.bw The divi- July 17, 2020 dend will be paid around the 25 th of August 200 appoint Sefalana group last week announced that the to shareholders registered by 14 th of the same board of directors ETFhas approved trading 27.5 thebe per up month. -

Concubinage and Union Libre: a Historical Comparison of the Rights of Unwed Cohabitants in Wrongful Death Actions in France and Louisiana

CONCUBINAGE AND UNION LIBRE: A HISTORICAL COMPARISON OF THE RIGHTS OF UNWED COHABITANTS IN WRONGFUL DEATH ACTIONS IN FRANCE AND LOUISIANA Robert F. Taylor* I. INTRODUCTION Across the centuries of western sociological and juridical thought the rights, requirements, and burdens placed on the marriage rela- tionship have reflected the ethical and moral customs of the area and the time. Because perceptions of ethical and moral right or wrong are continually in a state of flux, interpersonal relationships reflect that uncertainty; and because law can neither depart from ethical custom nor lag behind it, the law is also constantly evolving. For the majority of Americans, heterosexual cohabitation in a marriage relationship most often entails civil predicates such as blood tests, licenses and certificates, together with some sort of secular or religious solemnization. Yet today, more than ever before, the phenomenon of unwed cohabitation is not only alive and well, but is destined to expand even more dramatically in fu- ture years." The bureau of census statistics indicates that during the 1960's the number of persons living together "without benefit of clergy" increased by over seven hundred percent.2 By 1978 that figure had doubled again, to more than one million couples. Among persons under twenty-five years of age, the numbers had aug- mented eight fold.8 Indeed, the "practice of unwed cohabitation *Instructor from University of the Pacific, McGeorge School of Law at the Salzburg Insti- tute of International Law (Summer 1984); Doctoral candidate in French civil law at Univer- sity of Strasbourg, France (1984). Diplme, Langue des Affaires, University of Nice (1983); L.L.M., University of the Pacific, McGeorge School of Law (1982); J.D., Cumberland School of Law (1980); Member of the Alabama Bar. -

Antifeminism Online. MGTOW (Men Going Their Own Way)

Antifeminism Online MGTOW (Men Going Their Own Way) Jie Liang Lin INTRODUCTION Reactionary politics encompass various ideological strands within the online antifeminist community. In the mass media, events such as the 2014 Isla Vista killings1 or #gamergate,2 have brought more visibility to the phenomenon. Although antifeminism online is most commonly associated with middle- class white males, the community extends as far as female students and professionals. It is associated with terms such as: “Men’s Rights Movement” (MRM),3 “Meninism,”4 the “Red Pill,”5 the “Pick-Up Artist” (PUA),6 #gamergate, and “Men Going Their Own Way” (MGTOW)—the group on which I focused my study. I was interested in how MGTOW, an exclusively male, antifeminist group related to past feminist movements in theory, activism and community structure. I sought to understand how the internet affects “antifeminist” identity formation and articulation of views. Like many other antifeminist 1 | On May 23, 2014 Elliot Rodger, a 22-year old, killed six and injured 14 people in Isla Vista—near the University of California, Santa Barbara campus—as an act of retribution toward women who didn’t give him attention, and men who took those women away from him. Rodger kept a diary for three years in anticipation of his “endgame,” and subscribed to antifeminist “Pick-Up Artist” videos. http://edition.cnn.com/2014/05/26/justice/ california-elliot-rodger-timeline/ Accessed: March 28, 2016. 2 | #gamergate refers to a campaign of intimidation of female game programmers: Zoë Quinn, Brianna Wu and feminist critic Anita Sarkeesian, from 2014 to 2015. -

Thursday 26 November 2020 the First Meeting of the Second Session of the Twelfth Parliament English Version

THE FIRST MEETING OF THE SECOND SESSION OF THE TWELFTH PARLIAMENT THURSDAY 26 NOVEMBER 2020 ENGLISH VERSION HANSARD NO: 200 THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY SPEAKER The Hon. Phandu T. C. Skelemani PH, MP. DEPUTY SPEAKER The Hon. Mabuse M. Pule, MP. (Mochudi East) Clerk of the National Assembly - Ms B. N. Dithapo Deputy Clerk of the National Assembly - Mr L. T. Gaolaolwe Learned Parliamentary Counsel - Ms M. Mokgosi Assistant Clerk (E) - Mr R. Josiah CABINET His Excellency Dr M. E. K. Masisi, MP. - President His Honour S. Tsogwane, MP. (Boteti West) - Vice President Minister for Presidential Affairs, Governance and Public Hon. K. N. S. Morwaeng, MP. (Molepolole South) - Administration Hon. K. T. Mmusi, MP. (Gabane-Mmankgodi) - Minister of Defence, Justice and Security Hon. Dr L. Kwape, MP. (Kanye South) - Minister of International Affairs and Cooperation Hon. E. M. Molale, MP. (Goodhope-Mabule ) - Minister of Local Government and Rural Development Hon. K. S. Gare, MP. (Moshupa-Manyana) - Minister of Agricultural Development and Food Security Minister of Environment, Natural Resources Conservation Hon. P. K. Kereng, MP. (Specially Elected) - and Tourism Hon. Dr E. G. Dikoloti MP. (Mmathethe-Molapowabojang) - Minister of Health and Wellness Hon. T.M. Segokgo, MP. (Tlokweng) - Minister of Transport and Communications Hon. K. Mzwinila, MP. (Specially Elected) - Minister of Land Management, Water and Sanitation Services Minister of Youth Empowerment, Sport and Culture Hon. T. M. Rakgare, MP. (Mogoditshane) - Development Hon. A. M. Mokgethi, MP. (Gaborone Bonnington North) - Minister of Nationality, Immigration and Gender Affairs Hon. Dr T. Matsheka, MP. (Lobatse) - Minister of Finance and Economic Development Hon. F. M. M. -

Separation, Adultery, Children Born out of Wedlock

COI QUERY Country of Origin Philippines Main subject Separation, adultery, children born out of wedlock Question(s) 1) Legal framework of divorce in the Philippines, and its implementation/enforcement in practice; 2) Legal framework of adultery in the Philippines, and its implementation/enforcement in practice; 3) Societal consequences of adultery; 4) Separation Agreements in the Philippines and their legal effects; 5) Legal status of children born out of the wedlock and/or as result of adultery; 6) Societal attitude towards a child born out of wedlock and/or as result of adultery Date of completion 6 March 2020 Query Code Q5-2020 Contributing EU+ COI n/a units (if applicable) Disclaimer This response to a COI query has been elaborated according to the Common EU Guidelines for Processing COI and EASO COI Report Methodology. The information provided in this response has been researched, evaluated and processed with utmost care within a limited time frame. All sources used are referenced. A quality review has been performed in line with the above mentioned methodology. This document does not claim to be exhaustive neither conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to international protection. If a certain event, person or organisation is not mentioned in the report, this does not mean that the event has not taken place or that the person or organisation does not exist. Terminology used should not be regarded as indicative of a particular legal position. The information in the response does not necessarily reflect the opinion of EASO and makes no political statement whatsoever. The target audience is caseworkers, COI researchers, policy makers, and decision making authorities. -

Masisi to Reshuffle Cabinet 5

The Patriot on Sunday | www.thepatriot.co.bw | February 28, 2021 News 1 GAMBLING RAKES IN P79M - PAGE 3 |QUEER TRIBE WANT TO BE HEARD - PAGE 3 |MPS WARNED AGAINST GREED- PAGE 5 STOP COVID-19 WASH YOUR HANDS! www.thepatriot.co.bw FEBRUARY 28, 2021 | ISSUE 413 P12.00 Masisi to Curfew relaxed, Booze back! • Covid19 vaccines arrive in March, movement eased • Community based care takes centre stage • Alcohol sold on take-away during week days ONLY • Discotheque, night clubs remain closed reshuffle STAFF WRITERS living in Botswana will be eligible to of AstraZeneca, Covax and Pfizer [email protected] be given a dose. “The disease does not (suitable for people aged 16 and above) discrimate on gender, physical features vaccines. Other vaccines are suitable resident Mokgweetsi Masisi etc. Everybody will be given a dose. for people aged 18 years and above. has pleaded with Batswana to If we manage to secure excess doses Botswana has also entered P accept vaccination without we will share with our neighbours. into agreement in principle with cabinet any hiccups because the safety of any Countries that tried to close out other neighbouring Namibia for a back vaccine brought into the country nations have failed to contain the up on the procurement of Covid-19 • Fire, hire will be verified by Botswana Medical disease because the pandemic has vaccines should other avenues face interrupted by Regulatory Authority (BOMRA). affected everybody everywhere in the challenges. The two neoighbours Addressing the nation on Friday world,” said Masisi. have also encouraged universities in Namibia trip night, Masisi pleaded with community Reiterating the point, Deputy both countries to entere into a MoU leaders, civic organisations and Coordinator of the Presidential Task for research on the development of • Underperforming politicians to unite in encouraging Force Professor Mosepele Mosepele covid19 vaccine, Masisi revealed. -

General Assembly Distr.: General 22 February 2010

United Nations A/HRC/WG.6/8/LSO/1 General Assembly Distr.: General 22 February 2010 Original: English Human Rights Council Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review Eighth session Geneva, 3–14 May 2010 National report submitted in accordance with paragraph 15 (a) of the annex to Human Rights Council resolution 5/1* Lesotho * The present document was not edited before being sent to the United Nations translation services. GE.10-11075 A/HRC/WG.6/8/LSO/1 I. Methodology and consultation process 1. The methodology used in compiling this Report is a combination of desk research and stakeholder consultations through a series of workshops. The Human Rights Unit of the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights first developed a framework for the compilation of the Report. That was followed by consultative workshop held with all Government Ministries. A National workshop involving all stakeholders was then held to complement and validate the draft Report. II. Background: Normative and institutional framework A. Background (a) Geography 2. Lesotho is located in Southern Africa. It is landlocked and entirely surrounded by the Republic of South Africa. It covers an area of about 30555 square kilometres and has a population of about 1.88 million.1 (b) Political system 3. Lesotho is a constitutional monarchy. It gained independence from Britain on the 4th October, 1966. The King is the Head of State. There are three arms of Government, namely, the Executive, the Legislature and the Judiciary, to ensure checks and balances. The Head of Government is the Prime Minister. 4. Over the years, Lesotho’s democracy has been evolving and at times proved to be fragile. -

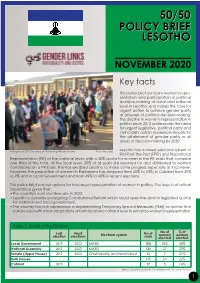

2020 Policy Brief

50/5050/50 POLICY BRIEF LESOTHO NOVEMBER 2020 Key facts This policy brief concerns women's repre- sentation and participation in political decision-making at local and national level in Lesotho, and makes the case for urgent action to achieve gender parity at all levels of political decision-making. The decline in women's representation in politics since 2012 underscores the need for urgent legislative, political party and civil society action as pressure mounts for the attainment of gender parity in all areas of decision-making by 2030. Voting in the 2017 elections at Malumeng Primary School, Photo: Ntolo Lekau Lesotho has a mixed electoral system of First-Past-The-Post (FPTP) and Proportional Representation (PR) at the national level, with a 30% quota for women in the PR seats that comprise one third of the total. At the local level, 30% of all seats are reserved for and distributed to women candidates on a PR basis. This has enabled Lesotho to make some progress especially at local level. However, the proportion of women in Parliament has dropped from 25% to 23%; in Cabinet from 29% to 9% and in Local Government and from 49% to 40% in recent elections. This policy brief sets out options for increased representation of women in politics. The issue is of critical importance given that: • The country's next elections are in 2022. •Lesotho is currently undergoing Constitutional Reform which could open the door to legislated quotas for national and local government. •The country has rich experience in implementing Temporary Special Measures (TSM) or quotas that can be used with minor adaptations at both local and national level to enhance women's representation. -

Contextualizing Liminality in Botswana Fiction and Reportage

THE COLLAPSE OF CERTAINTY: CONTEXTUALIZING LIMINALITY IN BOTSWANA FICTION AND REPORTAGE by FETSON ANDERSON KALUA submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF LITERATURE AND PHILOSOPHY in the subject ENGLISH at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA PROMOTER: PROF P D RYAN NOVEMBER 2007 Student No: 3115-208-2 DECLARATION I declare that The Collapse of Certainty: Contextualizing Liminality in Botswana Fiction and Reportage is my own work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. ------------------------------ --------------------- Signature Date (MR FA KALUA) ii Abstract The Collapse of Certainty: Contextualizing Liminality in Botswana’s Fiction and Reportage. This thesis deploys Homi Bhabha’s perspective of postcolonial literary theory as a critical procedure to examine particular instances of fiction, as well as reportage on Botswana. Its unifying interest is to pinpoint the shifting nature or reality of Botswana and, by extension, of African identities. To that end, I use Bhabha’s concept of liminality to inform the work of writers such as Unity Dow, Alexander McCall Smith, and instances of reportage (by Rupert Isaacson and Caitlin Davies), from the 1990s to date. The aims of the thesis are, among other things, to establish the extent to which Homi Bhabha’s appropriation of the term liminality (which derives from Victor Turner’s notion of limen for inbetweenness), and its application in the postcolonial context inflects the reading of the above works whose main motifs include the following: a contestation of any views which privilege one culture above another, challenging a jingoistic rootedness in one culture, and promoting an awareness of the existence of several, interlocking or even clashing realities which finally produce multiple meanings, values and identities.