'Implications of Lesotho's COVID-19 Response Framework for the Rule Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Assembly Distr.: General 22 February 2010

United Nations A/HRC/WG.6/8/LSO/1 General Assembly Distr.: General 22 February 2010 Original: English Human Rights Council Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review Eighth session Geneva, 3–14 May 2010 National report submitted in accordance with paragraph 15 (a) of the annex to Human Rights Council resolution 5/1* Lesotho * The present document was not edited before being sent to the United Nations translation services. GE.10-11075 A/HRC/WG.6/8/LSO/1 I. Methodology and consultation process 1. The methodology used in compiling this Report is a combination of desk research and stakeholder consultations through a series of workshops. The Human Rights Unit of the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights first developed a framework for the compilation of the Report. That was followed by consultative workshop held with all Government Ministries. A National workshop involving all stakeholders was then held to complement and validate the draft Report. II. Background: Normative and institutional framework A. Background (a) Geography 2. Lesotho is located in Southern Africa. It is landlocked and entirely surrounded by the Republic of South Africa. It covers an area of about 30555 square kilometres and has a population of about 1.88 million.1 (b) Political system 3. Lesotho is a constitutional monarchy. It gained independence from Britain on the 4th October, 1966. The King is the Head of State. There are three arms of Government, namely, the Executive, the Legislature and the Judiciary, to ensure checks and balances. The Head of Government is the Prime Minister. 4. Over the years, Lesotho’s democracy has been evolving and at times proved to be fragile. -

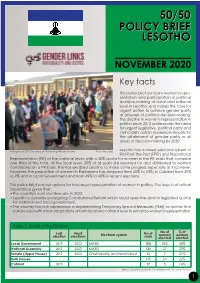

2020 Policy Brief

50/5050/50 POLICY BRIEF LESOTHO NOVEMBER 2020 Key facts This policy brief concerns women's repre- sentation and participation in political decision-making at local and national level in Lesotho, and makes the case for urgent action to achieve gender parity at all levels of political decision-making. The decline in women's representation in politics since 2012 underscores the need for urgent legislative, political party and civil society action as pressure mounts for the attainment of gender parity in all areas of decision-making by 2030. Voting in the 2017 elections at Malumeng Primary School, Photo: Ntolo Lekau Lesotho has a mixed electoral system of First-Past-The-Post (FPTP) and Proportional Representation (PR) at the national level, with a 30% quota for women in the PR seats that comprise one third of the total. At the local level, 30% of all seats are reserved for and distributed to women candidates on a PR basis. This has enabled Lesotho to make some progress especially at local level. However, the proportion of women in Parliament has dropped from 25% to 23%; in Cabinet from 29% to 9% and in Local Government and from 49% to 40% in recent elections. This policy brief sets out options for increased representation of women in politics. The issue is of critical importance given that: • The country's next elections are in 2022. •Lesotho is currently undergoing Constitutional Reform which could open the door to legislated quotas for national and local government. •The country has rich experience in implementing Temporary Special Measures (TSM) or quotas that can be used with minor adaptations at both local and national level to enhance women's representation. -

Gender Equality and Women's Empowerment

ACADEMIC PAPER GENDER EQUALITY AND WOMEN’S EMPOWERMENT: CONSTITUTIONAL JURISPRUDENCE MAY 2017 UN WOMEN © 2017 UN Women The electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribute- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information on this licence see: <http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/>. This publication is independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of UN Women, the Just Governance Group or International IDEA, or the view of their respective Boards or Council members. ACADEMIC PAPER GENDER EQUALITY AND WOMEN’S EMPOWERMENT: CONSTITUTIONAL JURISPRUDENCE UN WOMEN NEW YORK, MAY 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ...................................................... 7 Abbreviations ......................................................... 10 Executive Summary .................................................... 11 Recommendations. 11 Constitutional provisions .................................... 11 CEDAW and international instruments ......................... 12 Judicial reasoning ........................................... 12 Public-interest litigation approaches .......................... 12 Addressing gaps through further research. 12 1. Introduction -

Mental Disability and the Executive: a Comparative Analysis of the Separation of Powers

LCB_23_2_Article_6_Nelson (Do Not Delete) 6/13/2019 9:53 PM NOTES & COMMENTS MENTAL DISABILITY AND THE EXECUTIVE: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE SEPARATION OF POWERS by Zachary Nelson The doctrine of Separation of Powers is integral to the United States’ consti- tutional system. To prevent tyranny, governmental power must be separated to ensure that no government institution nor official gains too much power. The U.S. Constitution was drafted with this central concern in mind. To achieve successful separation of powers, constitutions must make clear—or at least discernible—the boundaries and scope of each power. One of the most significant areas in which this clarity is required is in the election, mainte- nance, and removal of the country’s executive leadership. For over 175 years, the U.S. Constitution lacked a procedure for removing its president from office for reasons of ill health. This was not due to a surplus of healthy presidents. In fact, the history of U.S. presidents is one of frequent illness, sudden traumas, and eleventh-hour miracles. Numerous presidents narrowly avoided death, while countless others kept hidden their struggles with physical frailty and decline. Beyond physical ailments, presidents endure stress * J.D., summa cum laude, Lewis & Clark Law School, 2019; M.A., Colorado State University, 2016; B.A., University of South Dakota, 2013. Thank you to Professor Ozan Varol for the valuable comments, feedback, and guidance during the drafting process, to the staff of the Lewis & Clark Law Review for their diligent work preparing this for publication, and to my family for their constant encouragement. -

Coalition Politics in Southern Africa Cover.Indd

AFRICA DIALOGUE Monograph Series No. 1/2018 COMPLEXITIES OF COALITION POLITICS IN SOUTHERN AFRICA The rise and fall of Lesotho’s coalition governments The Intricacies and Pitfalls of the Politics of Coalition in Mozambique The Politics of Dominance and Survival: Coalition Politics in South Africa 1994–2018 Complexities of Coalition Politics in Southern Africa Monograph Series No. 1/2018 Edited By: Senzo Ngubane ACCORD The Africa Dialogue Monograph Series is published by the African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD). ACCORD is a civil society institution working throughout Africa to bring creative African solutions to the challenges posted by conflict on the continent. ACCORD’s primary aim is to influence political developments by bringing conflict resolution, dialogue and institutional development to the forefront as an alternative to armed violence and protracted conflict. Disclaimer Views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of ACCORD. While every attempt has been made to ensure that the information published here is accurate, no responsibility is accepted for any loss or damage that may arise out of the reliance of any person upon any of the information this series contains. Copyright © 2018 ACCORD ISSN 1562–7004 This publication may be downloaded at no charge from the ACCORD website: <http://www.accord.org.za>. All rights reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. -

The Design of the Executive Branch

A Practical Guide to Constitution Building: The Design of the Executive Branch Markus Böckenförde This paper appears as chapter 4 of International IDEA’s publication A Practical Guide to Constitution Building. The full Guide is available in PDF and as an e-book at <http://www.idea.int> and includes an introductory chapter (chapter 1) and chapters on principles and cross-cutting themes in constitution building (chapter 2), building a culture of human rights (chapter 3), constitution building and the design of the legislature and the judiciary (chapters 5 and 6), and decentralized forms of government in relation to constitution building (chapter 7). International IDEA resources on Constitution Building A Practical Guide to Constitution Building: The Design of the Executive Branch © International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA), 2011 This publication is independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council of Member States, or those of the donors. Applications for permission to reproduce all or any part of this publication should be made to: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA) Strömsborg SE -103 34 Stockholm Sweden Tel: +46-8-698 37 00 Fax: +46-8-20 24 22 Email: [email protected] Website: www.idea.int Design and layout by: Turbo Design, Ramallah Printed by: Bulls Graphics, Sweden Cover design by: Turbo Design, Ramallah Cover illustration by: Sharif Sarhan ISBN: 978-91-86565-31-2 This publication is produced as part of the Constitution Building Programme implemented by International IDEA with funding from the Royal Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. -

Download/66807

CITIZENSHIP AND STATELESSNESS IN THE MEMBER STATES OF THE SOUTHERN AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT COMMUNITY DECEMBER 2020 Bronwen Manby CITIZENSHIP AND STATELESSNESS IN THE MEMBER STATES OF THE SOUTHERN AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT COMMUNITY 2020 Disclaimer This report may be quoted, cited, uploaded to other websites and copied, provided that the source is acknowledged. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of UNHCR. All names have been changed for the personal stories in boxes. Map of the 16 SADC Member States © UNHCR 2020 i UNHCR / December, 2020 CITIZENSHIP AND STATELESSNESS IN THE MEMBER STATES OF THE SOUTHERN AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT COMMUNITY 2020 Contents Disclaimer i Map of the 16 SADC Member States i Methodology and acknowledgments vi A note on terminology viii Summary 1 Extent of statelessness 1 Causes of statelessness 1 Groups at risk of statelessness 2 The impact of statelessness 2 International and African standards 3 Protection against statelessness in the legal frameworks of SADC states 3 Due process and transparency 4 Lack of access to naturalisation 5 Civil registration and identification 5 Regional cooperation and efforts to reduce statelessness 6 Overview of the report 7 Key recommendations 8 The history of nationality law in southern Africa 10 Migration and nationality since the colonial era 10 Transition to independence and initial frameworks of law 12 Post-independence trends 15 Comparative analysis of nationality legislation 17 Constitutional and legislative protection for the -

Customs and Constitutions: State Recognition of Customary Law Around the World

Customs and Constitutions: State recognition of customary law around the world Katrina Cuskelly i Customs and Constitutions: State recognition of customary law around the world Katrina Cuskelly ii The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN. Published by: IUCN, Asia Regional Office, Bangkok, Thailand Copyright: © 2011 IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Cuskelly, Katrina. (2011). Customs and Constitutions: State recognition of customary law around the world. IUCN, Bangkok, Thailand. vi + 151 pp. ISBN: 978-2-8317-1429-5 Produced by: IUCN Regional Environmental Law Programme, Asia, Bangkok, Thailand Cover image: Wheel of Dharma, Jokhang Monastery, Tibet © iStockphoto LP Available from: IUCN Publications Services, www.iucn.org/publications iii Table of Contents Foreword .......................................................................................................................... -

Download Article In

AFRICAN HUMAN RIGHTS LAW JOURNAL To cite: CM Fombad & LA Abdulrauf ‘Comparative overview of the constitutional framework for controlling the exercise of emergency powers in Africa’ (2020) 20 African Human Rights Law Journal 376-411 http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1996-2096/2020/v20n2a2 Comparative overview of the constitutional framework for controlling the exercise of emergency powers in Africa Charles Manga Fombad* Professor, Institute for International and Comparative Law in Africa, Faculty of Law, University of Pretoria, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7794-1496 Lukman Adebisi Abdulrauf** Senior Lecturer, Department of Public Law, University of Ilorin, Nigeria; Fellow, Institute for International and Comparative Law in Africa, Faculty of Law, University of Pretoria, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4877-9415 Summary: The need to act swiftly in times of emergency gives governments a reason to exercise emergency powers. This is a legally valid and accepted practice in modern democracies. Post-independence African constitutions contained provisions that sought to regulate states of emergency, placing the emphasis on who could make such declarations and what measures could be taken, but paid scant attention to the safeguards that were needed to ensure that the enormous powers that governments were allowed to accrue and exercise in dealing with emergencies were not abused. As a result, these broad powers were regularly used to abuse fundamental human rights and suppress opponents of the government. In the post-1990 wave of constitutional reforms in Africa, some attempts were made to introduce safeguards * Licence en Droit (Yaounde) LLM PhD (London); [email protected] * LLB (Zaria) LLM (Ilorin) LLD (Pretoria); [email protected] CONSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK FOR CONTROLLING EMERGENCY POWERS IN AFRICA 377 against the misuse of emergency powers. -

The Legislature

PARLIAMENTARY ROLE AND ITS RELATIONSHIP WITH ITS RELEVANT INSTITUTIONS IN EFFECTIVELY ADDRESSING CLIMATE CHANGE ISSUES-LESOTHO A study commissioned and supported by the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) in partnership with European Parliamentarians for Africa (AWEPA) September 2010 Prepared by „Manthatisi Margaret Machepha 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Part A A description of the Parliament; its make up; How Parliament business is conducted and its support Structures. 1. The Parliament of Lesotho 1.1 Mode of Elections 1.1.1 Section 55 Composition of the Senate 1.1.2 Section 56 Composition of National Assembly 1.2 The Senate and its functions 1.3 Challenges facing the Senate 1.4 The National Assembly 1.4.1 The Legislature 1.4.2 The Executive 1.4.3 Office of the Attorney General 1.4.4 Section 95 establishes a Council of State 1.4.5 Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions 1.4.6 The Judicature Part B 2. Policy/Legal Framework for Climate Change in Lesotho 2.1 Ministry of Natural Resources Parliamentarian Portfolio Committee 2 2.2 Lesotho Metereological Services 2.3Government Policies,Projects and Initiatives 2.4Mitigation Initiatives andMeasures 2.4.1 Adaptation Measures 2.5 Vulnerability of Lesotho to Climate Change 2.6 Climate Change Adaptation 2.7 Mitigation 2.8 Summary of Policies and Legislation, which directly or Indirectly address Climate Change 3. Parliament involvement in Climate Change Activities 3.1 Lesotho‟s participation in the UNFCC 3.2 Summary of meetings/Cabinet submissions and Parliamentarians presentations 3.3 Actual involvement of MPs 4. -

Lesotho Country Report BTI 2014

BTI 2014 | Lesotho Country Report Status Index 1-10 5.48 # 71 of 129 Political Transformation 1-10 6.25 # 57 of 129 Economic Transformation 1-10 4.71 # 88 of 129 Management Index 1-10 4.96 # 63 of 129 scale score rank trend This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2014. It covers the period from 31 January 2011 to 31 January 2013. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2014 — Lesotho Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2014. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. BTI 2014 | Lesotho 2 Key Indicators Population M 2.1 HDI 0.461 GDP p.c. $ 1963.1 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 1.1 HDI rank of 187 158 Gini Index 52.5 Life expectancy years 48.2 UN Education Index 0.501 Poverty3 % 62.3 Urban population % 28.3 Gender inequality2 0.534 Aid per capita $ 96.4 Sources: The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2013 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2013. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $2 a day. Executive Summary The period under review was characterized by changes that could determine whether economic stability lies ahead for Lesotho. The country held general elections on 26 May 2012, and Thomas Thabane, the leader of All Basotho Convention (ABC), became prime minister. -

Editorial by Paul E

PEDRO UGARTE/AFP PEDRO EDITORIAL BY PAUL E. NANTULYA his issue of Conflict Trends offers some background against which the latest constitutional insights into contemporary constitutional and electoral changes in her country have taken developments in Africa, both from a country place. She looks at the specific amendments, the Tspecific, to regional and more thematic issues. work of the Interim Political Authority and briefly The pieces have been contributed by a combina- touches on the new electoral system, which com- tion of constitutional experts, conflict management bines a first past the post system with a mixed specialists and political analysts. This mix, member proportional representation system, reflects ACCORD’s own thinking around constitu- widely seen as a compromise to offset the parlia- tional issues in Africa, which generally supports mentary imbalances created by the former system the view that constitutions have always been nego- in the 1998 elections. The country is expected to tiated, amended reviewed, or overthrown against a hold its next elections in April 2002. specific political context, and with concrete politi- Following this brief constitutional update on cal objectives in mind. They are also inevitably Lesotho, Prof. Severine Rugumamu, from the influenced by the prevailing conflict dynamics on Conflict Management Centre at the Organisation of the ground, which in turn cannot be separated African Unity, shares some insights into state sover- from the wider socio-economic and political milieu eignty and intervention in Africa. This particular within which the different political, social and theme, touching as it does on specific and broader other interest groups and formations manoeuvre questions of local and global governance, is now fil- for power, influence and reform.