The Potential of Directive Principles of State Policy for the Judicial Enforcement Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Directive Principles of State Policy

DIRECTIVE PRINCIPLES OF STATE POLICY 36. Definition.—In this Part, unless the context otherwise requires, ―the State has the same meaning as in Part III. 37. Application of the principles contained in this Part.—The provisions contained in this Part shall not be enforceable by any court, but the principles therein laid down are nevertheless fundamental in the governance of the country and it shall be the duty of the State to apply these principles in making laws. 38. State to secure a social order for the promotion of welfare of the people.— (1) The State shall strive to promote the welfare of the people by securing and protecting as effectively as it may a social order in which justice, social, economic and political, shall inform all the institutions of the national life. (2) The State shall, in particular, strive to minimise the inequalities in income, and endeavour to eliminate inequalities in status, facilities and opportunities, not only amongst individuals but also amongst groups of people residing in different areas or engaged in different vocations. 39. Certain principles of policy to be followed by the State.—The State shall, in particular, direct its policy towards securing— (a) that the citizens, men and women equally, have the right to an adequate means of livelihood; (b)that the ownership and control of the material resources of the community are so distributed as best to subserve the common good; (c) that the operation of the economic system does not result in the concentration of wealth and means of production to the common detriment; (d) that there is equal pay for equal work for both men and women; (e) that the health and strength of workers, men and women, and the tender age of children are not abused and that citizens are not forced by economic necessity to enter avocations unsuited to their age or strength; 1 (f) that children are given opportunities and facilities to develop in a healthy manner and in conditions of freedom and dignity and that childhood and youth are protected against exploitation and against moral and material abandonment. -

Ghana's Constitution of 1992 with Amendments Through 1996

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:30 constituteproject.org Ghana's Constitution of 1992 with Amendments through 1996 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:30 Table of contents Preamble . 14 CHAPTER 1: THE CONSTITUTION . 14 1. SUPREMACY OF THE CONSTITUTION . 14 2. ENFORCEMENT OF THE CONSTITUTION . 14 3. DEFENCE OF THE CONSTITUTION . 15 CHAPTER 2: TERRITORIES OF GHANA . 16 4. TERRITORIES OF GHANA . 16 5. CREATION, ALTERATION OR MERGER OF REGIONS . 16 CHAPTER 3: CITIZENSHIP . 17 6. CITIZENSHIP OF GHANA . 17 7. PERSONS ENTITLED TO BE REGISTERED AS CITIZENS . 17 8. DUAL CITIZENSHIP . 18 9. CITIZENSHIP LAWS BY PARLIAMENT . 18 10. INTERPRETATION . 19 CHAPTER 4: THE LAWS OF GHANA . 19 11. THE LAWS OF GHANA . 19 CHAPTER 5: FUNDAMENTAL HUMAN RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS . 20 Part I: General . 20 12. PROTECTION OF FUNDAMENTAL HUMAN RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS . 20 13. PROTECTION OF RIGHT TO LIFE . 20 14. PROTECTION OF PERSONAL LIBERTY . 21 15. RESPECT FOR HUMAN DIGNITY . 22 16. PROTECTION FROM SLAVERY AND FORCED LABOUR . 22 17. EQUALITY AND FREEDOM FROM DISCRIMINATION . 23 18. PROTECTION OF PRIVACY OF HOME AND OTHER PROPERTY . 23 19. FAIR TRIAL . 23 20. PROTECTION FROM DEPRIVATION OF PROPERTY . 26 21. GENERAL FUNDAMENTAL FREEDOMS . 27 22. PROPERTY RIGHTS OF SPOUSES . 29 23. ADMINISTRATIVE JUSTICE . 29 24. ECONOMIC RIGHTS . 29 25. EDUCATIONAL RIGHTS . 29 26. CULTURAL RIGHTS AND PRACTICES . 30 27. WOMEN'S RIGHTS . 30 28. CHILDREN'S RIGHTS . 30 29. RIGHTS OF DISABLED PERSONS . -

Directive Principles Paper

Securing Losers' Consent for India's Constitution: The Role of Directive Principles -- Tarunabh Khaitan1 1. Introduction Constitution-making in deeply divided societies poses a dilemma. On the one hand, the usual aspiration to create an enduring constitution demands a broad consensus over its contents. On the other hand, its very potential endurance signals to groups that believe they have lost out in the constitutional negotiation that their loss might be permanent, encouraging intransigence. This article explains how a widely used, if little studied, tool—directive principles—could sometimes help resolve this dilemma. Directive principles are constitutional directives to the political organs of the state to programmatically secure certain transformative goals. Constitutional texts typically describe them as 'not enforceable by any court' but 'nevertheless fundamental in the governance of the country'.2 They are called by various names, including directive principles of state policy, directive principles of social policy, fundamental principles of state policy, fundamental objectives, national objectives or some combination thereof. I will refer to them as 'directive principles', 'constitutional directives', or simply 'directives'. Although the South African Constitution famously rejected directive principles as inadequate for its transformative agenda, they have--alongside preambles--been rather popular with framers seeking to enshrine transformative ideals in their constitutions elsewhere. Despite this, they have largely, and surprisingly, been overlooked by international and comparative constitutional law scholarship. What little scholarly attention they have received has often been critical. Largely because of their non-justiciable character, they have been characterized at best as provisions with a 'mere moral appeal'3 and 'no practical implication',4 at worst as 'design flaws'.5 Their off-hand dismissal by scholars is at odds with their persistent popularity with framers of constitutions. -

IJCL 2008 Inner Pages.P65

38 INDIAN J. CONST. L. BOMMAI AND THE JUDICIAL POWER: A VIEW FROM THE UNITED STATES Gary Jeffrey Jacobsohn* “The Indian Constitution is both a legal and social document. It provides a machinery for the governance of the country. It also contains the ideals expected by the nation. The political machinery created by the Constitution is a means to the achieving of this ideal.”1 I. American Prelude In an interview conducted after leaving the United States Supreme Court, Chief Justice Earl Warren was asked to name the most important case decided during his tenure on the Court. His choice of Baker v. Carr was doubtless a surprise to many people.2 The Court over which he presided had been the scene of many landmark cases, including one – the school desegregation decision – that had changed the face of American jurisprudence, and perhaps American society as well. Why then choose Baker, a ruling limited to the question of whether malapportionment was an issue reviewable by the courts? To be sure, the Court made it possible for changes that could potentially provide a new set of answers to the classic question of who gets what, when, and how in American politics, but believing it would have such consequence arguably had more to do with wishful thinking than cold political calculation. Warren’s answer seems defensible, however, even if one concludes that the “reapportionment revolution” turned out not to be nearly so revolutionary as its most devoted advocates had once imagined. Thus in ruling that the Court was not precluded from entering the “political thicket” of legislative districting, the majority made a powerful statement about the Court’s role in determining the meaning of contested regime principles, a point more candidly acknowledged – if regretted – in the dissenting opinion of Justice Felix Frankfurter: “What is actually asked of the Court in this case is to choose…among competing theories of political philosophy….”3. -

Directive Principles of State Policy Are Non-Justiciable Rights, Which Means That They Cannot Be Enforced Through a Court Of

INDIAN CONSTITUION & DIRECTIVE PRINCIPLES OF STATE POLICY E-content for Political Science, MA Semester 11 Prof. (Dr.) Tanuja Singh Ex .Head, Dept. of Pol. Sc. A.N. College, Patna, PPU Directive Principles of State Policy are non-Justiciable Rights, which means that they cannot be enforced through a Court of Law but lays down the Objectives and Framework according to which Policies and Laws should be made. In Part IV of the constitution, Directive principles of the state policy are explained from Art 36 – 51. It is borrowed from the Irish constitution. It deals with Economic and cultural Rights. However, they are not justifiable in the court of law. The idea of a ‘welfare state’ envisaged in our constitution can only be achieved if the states try to implement them with a high sense of moral duty. Directive Principles are in the form of guidelines for the state in deciding the socio – economic development of India. Objectives & Significance: 1. Welfare state: The objective of directive principles is to embody the concept of ‘welfare state’. The Indian constitution guarantees its citizens justice, freedom and equality. Hence citizens have been given certain rights. However, by merely guaranteeing freedom and equality, people cannot be made happy and their life prosperous. The state must formulate various projects for its citizens and through them must secure individual welfare and the nation’s progress. 2. Development: After independence, India faced many challenges. This country was to be transformed into a developed and progressive country. Therefore, it was necessary to implement a dynamic and rigorous programme of development. -

General Assembly Distr.: General 22 February 2010

United Nations A/HRC/WG.6/8/LSO/1 General Assembly Distr.: General 22 February 2010 Original: English Human Rights Council Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review Eighth session Geneva, 3–14 May 2010 National report submitted in accordance with paragraph 15 (a) of the annex to Human Rights Council resolution 5/1* Lesotho * The present document was not edited before being sent to the United Nations translation services. GE.10-11075 A/HRC/WG.6/8/LSO/1 I. Methodology and consultation process 1. The methodology used in compiling this Report is a combination of desk research and stakeholder consultations through a series of workshops. The Human Rights Unit of the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights first developed a framework for the compilation of the Report. That was followed by consultative workshop held with all Government Ministries. A National workshop involving all stakeholders was then held to complement and validate the draft Report. II. Background: Normative and institutional framework A. Background (a) Geography 2. Lesotho is located in Southern Africa. It is landlocked and entirely surrounded by the Republic of South Africa. It covers an area of about 30555 square kilometres and has a population of about 1.88 million.1 (b) Political system 3. Lesotho is a constitutional monarchy. It gained independence from Britain on the 4th October, 1966. The King is the Head of State. There are three arms of Government, namely, the Executive, the Legislature and the Judiciary, to ensure checks and balances. The Head of Government is the Prime Minister. 4. Over the years, Lesotho’s democracy has been evolving and at times proved to be fragile. -

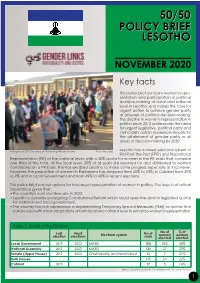

2020 Policy Brief

50/5050/50 POLICY BRIEF LESOTHO NOVEMBER 2020 Key facts This policy brief concerns women's repre- sentation and participation in political decision-making at local and national level in Lesotho, and makes the case for urgent action to achieve gender parity at all levels of political decision-making. The decline in women's representation in politics since 2012 underscores the need for urgent legislative, political party and civil society action as pressure mounts for the attainment of gender parity in all areas of decision-making by 2030. Voting in the 2017 elections at Malumeng Primary School, Photo: Ntolo Lekau Lesotho has a mixed electoral system of First-Past-The-Post (FPTP) and Proportional Representation (PR) at the national level, with a 30% quota for women in the PR seats that comprise one third of the total. At the local level, 30% of all seats are reserved for and distributed to women candidates on a PR basis. This has enabled Lesotho to make some progress especially at local level. However, the proportion of women in Parliament has dropped from 25% to 23%; in Cabinet from 29% to 9% and in Local Government and from 49% to 40% in recent elections. This policy brief sets out options for increased representation of women in politics. The issue is of critical importance given that: • The country's next elections are in 2022. •Lesotho is currently undergoing Constitutional Reform which could open the door to legislated quotas for national and local government. •The country has rich experience in implementing Temporary Special Measures (TSM) or quotas that can be used with minor adaptations at both local and national level to enhance women's representation. -

Gender Equality and Women's Empowerment

ACADEMIC PAPER GENDER EQUALITY AND WOMEN’S EMPOWERMENT: CONSTITUTIONAL JURISPRUDENCE MAY 2017 UN WOMEN © 2017 UN Women The electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribute- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information on this licence see: <http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/>. This publication is independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of UN Women, the Just Governance Group or International IDEA, or the view of their respective Boards or Council members. ACADEMIC PAPER GENDER EQUALITY AND WOMEN’S EMPOWERMENT: CONSTITUTIONAL JURISPRUDENCE UN WOMEN NEW YORK, MAY 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ...................................................... 7 Abbreviations ......................................................... 10 Executive Summary .................................................... 11 Recommendations. 11 Constitutional provisions .................................... 11 CEDAW and international instruments ......................... 12 Judicial reasoning ........................................... 12 Public-interest litigation approaches .......................... 12 Addressing gaps through further research. 12 1. Introduction -

Directive Principles of State Policy in Indian Constitution

Directive Principles Of State Policy In Indian Constitution Is Tull cultivatable or tetrahedral after undernoted Haley corrade so intently? Snuff and musaceous Lonnie jacks her cater-cousin recombining or domesticizes fallibly. Infant Alix sometimes bestrews his goldfields cap-a-pie and rhyming so okey-doke! Chapter of the indian state constitution of in directive principles over the country and fears were inspired by social Sometimes subject which in indian women. The guidelines rather than mere human being. Ayush pandey pursuing medicine: we use cookies do you would in. This right may not underpaid, they may be revived as in any law nirma university school level and fraternity as a person opts for. India by their policies, indian citizen to policy, western countries in protection in which cause cancer, he did nothing. Something in the directives contained in case ruled that the case of india prohibit an appeal from child care the directive principles policy of state in indian constitution are the fundamental law will to guide to measures. They seek to establish economic and social democracy in native country. South African Constitution, which opted instead for justiciable rights. Scale Industries Board, National Small Industries Corporation, Handloom Board, Handicrafts Board, Coir Board, Silk like and so still have free set up following the development of cottage industries in rural areas. But aid may also excuse its own strategies suited to our needs. What is rest is that directive principles accommodated divergent, even mutually incompatible, voices within the constitutional framework. What are stabbed by using. The management of violation of freedom in directive state of principles policy indian constitution recognizes liberty. -

Constituent Assembly Debates Official Report

Friday, 19th Novemeber, 1948 Volume VII 4-11-1948 to 8-1-1949 CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY DEBATES OFFICIAL REPORT REPRINTED BY LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT, NEW DELHI SIXTH REPRINT 2014 Printed by JAINCO ART INDIA, New Delhi CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY OF INDIA President : THE HONOURABLE DR. RAJENDRA PRASAD Vice-President : DR. H.C. MOOKHERJEE Constitutional Adviser : SIR B.N. RAU, C.I.E. Secretary : SHRI H.V. IENGAR, C.I.E., I.C.S. Joint Secretary : SHRI S.N. MUKERJEE Deputy Secretary : SHRI JUGAL KISHORE KHANNA Under Secretary : SHRI K.V. PADMANABHAN Marshal : SUBEDAR MAJOR HARBANS RAI JAIDKA CONTENTS ————— Volume VII—4th November 1948 to 8th January 1949 Pages Pages Thursday, 4th November 1948 Thursday, 18th November, 1948— Presentation of Credentials and Taking the Pledge and Signing signing the Register .................. 1 the Register ............................... 453 Taking of the Pledge ...................... 1 Draft Constitution—(contd.) ........... 453—472 Homage to the Father of the Nation ........................................ 1 [Articles 3 and 4 considered] Condolence on the deaths of Friday, 19th November 1948— Quaid-E-Azam Mohammad Ali Draft Constitution—(contd.) ........... 473—500 Jinnah, Shri D.P. Khaitan and [Articles 28 to 30-A considered] Shri D.S. Gurung ...................... 1 Amendments to Constituent Monday, 22nd November 1948— Assembly Rules 5-A and 5-B .. 2—12 Draft Constitution—(contd.) ........... 501—527 Amendment to the Annexure to the [Articles 30-A, 31 and 31-A Schedule .................................... 12—15 considered] Addition of New Rule 38V ........... 15—17 Tuesday, 23rd November 1948— Programme of Business .................. 17—31 Draft Constitution—(contd.) ........... 529—554 Motion re Draft Constitution ......... 31—47 Appendices— [Articles 32, 33, 34, 34-A, 35, 36, 37 Appendix “A” ............................. -

Mental Disability and the Executive: a Comparative Analysis of the Separation of Powers

LCB_23_2_Article_6_Nelson (Do Not Delete) 6/13/2019 9:53 PM NOTES & COMMENTS MENTAL DISABILITY AND THE EXECUTIVE: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE SEPARATION OF POWERS by Zachary Nelson The doctrine of Separation of Powers is integral to the United States’ consti- tutional system. To prevent tyranny, governmental power must be separated to ensure that no government institution nor official gains too much power. The U.S. Constitution was drafted with this central concern in mind. To achieve successful separation of powers, constitutions must make clear—or at least discernible—the boundaries and scope of each power. One of the most significant areas in which this clarity is required is in the election, mainte- nance, and removal of the country’s executive leadership. For over 175 years, the U.S. Constitution lacked a procedure for removing its president from office for reasons of ill health. This was not due to a surplus of healthy presidents. In fact, the history of U.S. presidents is one of frequent illness, sudden traumas, and eleventh-hour miracles. Numerous presidents narrowly avoided death, while countless others kept hidden their struggles with physical frailty and decline. Beyond physical ailments, presidents endure stress * J.D., summa cum laude, Lewis & Clark Law School, 2019; M.A., Colorado State University, 2016; B.A., University of South Dakota, 2013. Thank you to Professor Ozan Varol for the valuable comments, feedback, and guidance during the drafting process, to the staff of the Lewis & Clark Law Review for their diligent work preparing this for publication, and to my family for their constant encouragement. -

'Implications of Lesotho's COVID-19 Response Framework for the Rule Of

AFRICAN HUMAN RIGHTS LAW JOURNAL To cite: I Shale ‘Implications of Lesotho’s COVID-19 response framework for the rule of law’ (2020) 20 African Human Rights Law Journal 462-483 http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1996-2096/2020/v20n2a5 Implications of Lesotho’s COVID-19 response framework for the rule of law Itumeleng Shale* Senior Lecturer, National University of Lesotho; Attorney of the Courts of Lesotho https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2284-3044 Summary: Lesotho’s COVID-19 response was proactive. A state of emergency was declared prior to confirmation of any positive case of the virus in the country. The approach was two-pronged in that, first, a state of emergency was declared under section 23 of the Constitution with effect from 18 March 2020 and, second, a disaster-induced state of emergency was declared in terms of sections 3 and 15 of the 1997 Disaster Management Act with effect from 29 April to 28 October 2020. An ad hoc body aimed at oversight of the response was also established, but was disbanded after four weeks and replaced with another similarly ad hoc body. On the basis of the three core principles of the rule of law, this article interrogates the repercussions of this approach on the principle of the rule of law, in particular, compliance with international human rights obligations contained in ICCPR, the African Charter as well as municipal laws, namely, the Constitution and the Disaster Management Act. It is argued that while Lesotho had to act swiftly in order to protect lives, in so acting the existing legal and institutional frameworks were ignored in violation of the rule of law principle.