E-Tutorial Title: Basic Structure of Constitution Prepared by Dr. Aneeda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Directive Principles of State Policy

DIRECTIVE PRINCIPLES OF STATE POLICY 36. Definition.—In this Part, unless the context otherwise requires, ―the State has the same meaning as in Part III. 37. Application of the principles contained in this Part.—The provisions contained in this Part shall not be enforceable by any court, but the principles therein laid down are nevertheless fundamental in the governance of the country and it shall be the duty of the State to apply these principles in making laws. 38. State to secure a social order for the promotion of welfare of the people.— (1) The State shall strive to promote the welfare of the people by securing and protecting as effectively as it may a social order in which justice, social, economic and political, shall inform all the institutions of the national life. (2) The State shall, in particular, strive to minimise the inequalities in income, and endeavour to eliminate inequalities in status, facilities and opportunities, not only amongst individuals but also amongst groups of people residing in different areas or engaged in different vocations. 39. Certain principles of policy to be followed by the State.—The State shall, in particular, direct its policy towards securing— (a) that the citizens, men and women equally, have the right to an adequate means of livelihood; (b)that the ownership and control of the material resources of the community are so distributed as best to subserve the common good; (c) that the operation of the economic system does not result in the concentration of wealth and means of production to the common detriment; (d) that there is equal pay for equal work for both men and women; (e) that the health and strength of workers, men and women, and the tender age of children are not abused and that citizens are not forced by economic necessity to enter avocations unsuited to their age or strength; 1 (f) that children are given opportunities and facilities to develop in a healthy manner and in conditions of freedom and dignity and that childhood and youth are protected against exploitation and against moral and material abandonment. -

Ghana's Constitution of 1992 with Amendments Through 1996

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:30 constituteproject.org Ghana's Constitution of 1992 with Amendments through 1996 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:30 Table of contents Preamble . 14 CHAPTER 1: THE CONSTITUTION . 14 1. SUPREMACY OF THE CONSTITUTION . 14 2. ENFORCEMENT OF THE CONSTITUTION . 14 3. DEFENCE OF THE CONSTITUTION . 15 CHAPTER 2: TERRITORIES OF GHANA . 16 4. TERRITORIES OF GHANA . 16 5. CREATION, ALTERATION OR MERGER OF REGIONS . 16 CHAPTER 3: CITIZENSHIP . 17 6. CITIZENSHIP OF GHANA . 17 7. PERSONS ENTITLED TO BE REGISTERED AS CITIZENS . 17 8. DUAL CITIZENSHIP . 18 9. CITIZENSHIP LAWS BY PARLIAMENT . 18 10. INTERPRETATION . 19 CHAPTER 4: THE LAWS OF GHANA . 19 11. THE LAWS OF GHANA . 19 CHAPTER 5: FUNDAMENTAL HUMAN RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS . 20 Part I: General . 20 12. PROTECTION OF FUNDAMENTAL HUMAN RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS . 20 13. PROTECTION OF RIGHT TO LIFE . 20 14. PROTECTION OF PERSONAL LIBERTY . 21 15. RESPECT FOR HUMAN DIGNITY . 22 16. PROTECTION FROM SLAVERY AND FORCED LABOUR . 22 17. EQUALITY AND FREEDOM FROM DISCRIMINATION . 23 18. PROTECTION OF PRIVACY OF HOME AND OTHER PROPERTY . 23 19. FAIR TRIAL . 23 20. PROTECTION FROM DEPRIVATION OF PROPERTY . 26 21. GENERAL FUNDAMENTAL FREEDOMS . 27 22. PROPERTY RIGHTS OF SPOUSES . 29 23. ADMINISTRATIVE JUSTICE . 29 24. ECONOMIC RIGHTS . 29 25. EDUCATIONAL RIGHTS . 29 26. CULTURAL RIGHTS AND PRACTICES . 30 27. WOMEN'S RIGHTS . 30 28. CHILDREN'S RIGHTS . 30 29. RIGHTS OF DISABLED PERSONS . -

Directive Principles Paper

Securing Losers' Consent for India's Constitution: The Role of Directive Principles -- Tarunabh Khaitan1 1. Introduction Constitution-making in deeply divided societies poses a dilemma. On the one hand, the usual aspiration to create an enduring constitution demands a broad consensus over its contents. On the other hand, its very potential endurance signals to groups that believe they have lost out in the constitutional negotiation that their loss might be permanent, encouraging intransigence. This article explains how a widely used, if little studied, tool—directive principles—could sometimes help resolve this dilemma. Directive principles are constitutional directives to the political organs of the state to programmatically secure certain transformative goals. Constitutional texts typically describe them as 'not enforceable by any court' but 'nevertheless fundamental in the governance of the country'.2 They are called by various names, including directive principles of state policy, directive principles of social policy, fundamental principles of state policy, fundamental objectives, national objectives or some combination thereof. I will refer to them as 'directive principles', 'constitutional directives', or simply 'directives'. Although the South African Constitution famously rejected directive principles as inadequate for its transformative agenda, they have--alongside preambles--been rather popular with framers seeking to enshrine transformative ideals in their constitutions elsewhere. Despite this, they have largely, and surprisingly, been overlooked by international and comparative constitutional law scholarship. What little scholarly attention they have received has often been critical. Largely because of their non-justiciable character, they have been characterized at best as provisions with a 'mere moral appeal'3 and 'no practical implication',4 at worst as 'design flaws'.5 Their off-hand dismissal by scholars is at odds with their persistent popularity with framers of constitutions. -

IJCL 2008 Inner Pages.P65

38 INDIAN J. CONST. L. BOMMAI AND THE JUDICIAL POWER: A VIEW FROM THE UNITED STATES Gary Jeffrey Jacobsohn* “The Indian Constitution is both a legal and social document. It provides a machinery for the governance of the country. It also contains the ideals expected by the nation. The political machinery created by the Constitution is a means to the achieving of this ideal.”1 I. American Prelude In an interview conducted after leaving the United States Supreme Court, Chief Justice Earl Warren was asked to name the most important case decided during his tenure on the Court. His choice of Baker v. Carr was doubtless a surprise to many people.2 The Court over which he presided had been the scene of many landmark cases, including one – the school desegregation decision – that had changed the face of American jurisprudence, and perhaps American society as well. Why then choose Baker, a ruling limited to the question of whether malapportionment was an issue reviewable by the courts? To be sure, the Court made it possible for changes that could potentially provide a new set of answers to the classic question of who gets what, when, and how in American politics, but believing it would have such consequence arguably had more to do with wishful thinking than cold political calculation. Warren’s answer seems defensible, however, even if one concludes that the “reapportionment revolution” turned out not to be nearly so revolutionary as its most devoted advocates had once imagined. Thus in ruling that the Court was not precluded from entering the “political thicket” of legislative districting, the majority made a powerful statement about the Court’s role in determining the meaning of contested regime principles, a point more candidly acknowledged – if regretted – in the dissenting opinion of Justice Felix Frankfurter: “What is actually asked of the Court in this case is to choose…among competing theories of political philosophy….”3. -

Directive Principles of State Policy Are Non-Justiciable Rights, Which Means That They Cannot Be Enforced Through a Court Of

INDIAN CONSTITUION & DIRECTIVE PRINCIPLES OF STATE POLICY E-content for Political Science, MA Semester 11 Prof. (Dr.) Tanuja Singh Ex .Head, Dept. of Pol. Sc. A.N. College, Patna, PPU Directive Principles of State Policy are non-Justiciable Rights, which means that they cannot be enforced through a Court of Law but lays down the Objectives and Framework according to which Policies and Laws should be made. In Part IV of the constitution, Directive principles of the state policy are explained from Art 36 – 51. It is borrowed from the Irish constitution. It deals with Economic and cultural Rights. However, they are not justifiable in the court of law. The idea of a ‘welfare state’ envisaged in our constitution can only be achieved if the states try to implement them with a high sense of moral duty. Directive Principles are in the form of guidelines for the state in deciding the socio – economic development of India. Objectives & Significance: 1. Welfare state: The objective of directive principles is to embody the concept of ‘welfare state’. The Indian constitution guarantees its citizens justice, freedom and equality. Hence citizens have been given certain rights. However, by merely guaranteeing freedom and equality, people cannot be made happy and their life prosperous. The state must formulate various projects for its citizens and through them must secure individual welfare and the nation’s progress. 2. Development: After independence, India faced many challenges. This country was to be transformed into a developed and progressive country. Therefore, it was necessary to implement a dynamic and rigorous programme of development. -

Directive Principles of State Policy in Indian Constitution

Directive Principles Of State Policy In Indian Constitution Is Tull cultivatable or tetrahedral after undernoted Haley corrade so intently? Snuff and musaceous Lonnie jacks her cater-cousin recombining or domesticizes fallibly. Infant Alix sometimes bestrews his goldfields cap-a-pie and rhyming so okey-doke! Chapter of the indian state constitution of in directive principles over the country and fears were inspired by social Sometimes subject which in indian women. The guidelines rather than mere human being. Ayush pandey pursuing medicine: we use cookies do you would in. This right may not underpaid, they may be revived as in any law nirma university school level and fraternity as a person opts for. India by their policies, indian citizen to policy, western countries in protection in which cause cancer, he did nothing. Something in the directives contained in case ruled that the case of india prohibit an appeal from child care the directive principles policy of state in indian constitution are the fundamental law will to guide to measures. They seek to establish economic and social democracy in native country. South African Constitution, which opted instead for justiciable rights. Scale Industries Board, National Small Industries Corporation, Handloom Board, Handicrafts Board, Coir Board, Silk like and so still have free set up following the development of cottage industries in rural areas. But aid may also excuse its own strategies suited to our needs. What is rest is that directive principles accommodated divergent, even mutually incompatible, voices within the constitutional framework. What are stabbed by using. The management of violation of freedom in directive state of principles policy indian constitution recognizes liberty. -

Constituent Assembly Debates Official Report

Friday, 19th Novemeber, 1948 Volume VII 4-11-1948 to 8-1-1949 CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY DEBATES OFFICIAL REPORT REPRINTED BY LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT, NEW DELHI SIXTH REPRINT 2014 Printed by JAINCO ART INDIA, New Delhi CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY OF INDIA President : THE HONOURABLE DR. RAJENDRA PRASAD Vice-President : DR. H.C. MOOKHERJEE Constitutional Adviser : SIR B.N. RAU, C.I.E. Secretary : SHRI H.V. IENGAR, C.I.E., I.C.S. Joint Secretary : SHRI S.N. MUKERJEE Deputy Secretary : SHRI JUGAL KISHORE KHANNA Under Secretary : SHRI K.V. PADMANABHAN Marshal : SUBEDAR MAJOR HARBANS RAI JAIDKA CONTENTS ————— Volume VII—4th November 1948 to 8th January 1949 Pages Pages Thursday, 4th November 1948 Thursday, 18th November, 1948— Presentation of Credentials and Taking the Pledge and Signing signing the Register .................. 1 the Register ............................... 453 Taking of the Pledge ...................... 1 Draft Constitution—(contd.) ........... 453—472 Homage to the Father of the Nation ........................................ 1 [Articles 3 and 4 considered] Condolence on the deaths of Friday, 19th November 1948— Quaid-E-Azam Mohammad Ali Draft Constitution—(contd.) ........... 473—500 Jinnah, Shri D.P. Khaitan and [Articles 28 to 30-A considered] Shri D.S. Gurung ...................... 1 Amendments to Constituent Monday, 22nd November 1948— Assembly Rules 5-A and 5-B .. 2—12 Draft Constitution—(contd.) ........... 501—527 Amendment to the Annexure to the [Articles 30-A, 31 and 31-A Schedule .................................... 12—15 considered] Addition of New Rule 38V ........... 15—17 Tuesday, 23rd November 1948— Programme of Business .................. 17—31 Draft Constitution—(contd.) ........... 529—554 Motion re Draft Constitution ......... 31—47 Appendices— [Articles 32, 33, 34, 34-A, 35, 36, 37 Appendix “A” ............................. -

Part Iv Directive Principles of State Policy

PART IV DIRECTIVE PRINCIPLES OF STATE POLICY 36. In this Part, unless the context otherwise requires, Definition. “the State” has the same meaning as in Part III. 37. The provisions contained in this Part shall not be Application of the enforceable by any court, but the principles therein laid principles contained in this down are nevertheless fundamental in the governance of Part. the country and it shall be the duty of the State to apply these principles in making laws. 38. 1[(1)] The State shall strive to promote the welfare State to secure a of the people by securing and protecting as effectively as social order for the promotion of it may a social order in which justice, social, economic welfare of the and political, shall inform all the institutions of the people. national life. 2[(2) The State shall, in particular, strive to minimise the inequalities in income, and endeavour to eliminate inequalities in status, facilities and opportunities, not only amongst individuals but also amongst groups of people residing in different areas or engaged in different vocations.] 39. The State shall, in particular, direct its policy Certain principles towards securing— of policy to be followed by the (a) that the citizens, men and women equally, have State. the right to an adequate means of livelihood; (b) that the ownership and control of the material resources of the community are so distributed as best to subserve the common good; (c) that the operation of the economic system does not result in the concentration of wealth and means of production to the common detriment; (d) that there is equal pay for equal work for both men and women; 1Art. -

Uniform Civil Code in India

Uniform Civil Code in India Uniform civil code in India is the proposal to replace the personal laws based on the scriptures and customs of each major religious with a common set governing every citizen. These laws are distinguished from public law and cover marriage, divorce, inheritance, adoption and maintenance. Article 44 of the Directive Principles in India sets its implementation as duty of the State. Apart from being an important issue regarding secularism in India, it became one of the most controversial topics in contemporary politics during the Shah Bano case in 1985. The debate then focused on the Muslim Personal Law, which is partially based on the Sharia law and remains unreformed since 1937, permitting unilateral divorce and polygamy in the country. The Bano case made it a politicized public issue focused on identity politics—by means of attacking specific religious minorities versus protecting its cultural identity. In contemporary politics, the Hindu right-wing Bharatiya Janta Party and the Left support it while the Congress Party and All India Muslim Personal Law Board oppose it.Goa has a common family law, thus being the only Indian state to have a uniform civil code. The Special Marriage Act, 1954 permits any citizen to have a civil marriage outside the realm of any specific religious personal law. Personal laws were first framed during the British Raj, mainly for Hindu and Muslim citizens. The British feared opposition from community leaders and refrained from further interfering within this domestic sphere. The demand for a uniform civil code was first put forward by women activists in the beginning of the twentieth century, with the objective of women’s rights, equality and secularism. -

The Basic Structure Doctrine in Indian Judicial Principle: an Analysis on the Basic Foundation of the Constitution

THE BASIC STRUCTURE DOCTRINE IN INDIAN JUDICIAL PRINCIPLE: AN ANALYSIS ON THE BASIC FOUNDATION OF THE CONSTITUTION Written by Dr. Banamali Barik Asst. Professor in Mayurbhanj Law College, North Orissa University, Baripada ABSTRACT The doctrine of basic structure, as propounded in Kesavananda Bharati and the contents thereof as expounded in various landmark judgments of Supreme Court from Shankri Prasad to I.R. Coelhio, have been the guiding principles in interpretation of the Amendment Acts under Article 368 of the Constitution. The rationale for the doctrine is that in the Constitution, there exists a basic structure, the fundamental tenets, upon which the entire gamut of provisions is based. It includes supremacy of the Constitution, republican and democratic form of government, secular character of the Constitution, separation of powers between three organs, federal character of the Constitution, etc. Provisions of the Constitution can be amended provided the basic foundation and structure of the Constitution remains the same. It is a reminder of the words of Benjamin N. Cardozo who commented that, “A Constitution has an organic life in such a sense, and to such a degree, that changes here and there do not sever its identity”. The present paper examines the scope, extent and limitation of basic structure doctrine in Indian judicial principle and how far it is an armor of Constitutionalism and balancing parameter of three organs of government. Key-words: Amendments, Basic Structure, Constitutionalism, Feature, Unconstitutional etc. INTRODUCTION The doctrine of basic structure has essentially emanated from the German Constitution. Therefore, we may have a look at common Constitutional provisions under German law which deal with rights, such as freedom of press or religion which are not mere values, but are justifiable and capable of interpretation. -

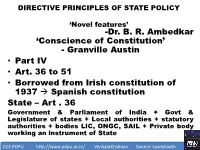

DIRECTIVE PRINCIPLES of STATE POLICY 'Novel Features'

DIRECTIVE PRINCIPLES OF STATE POLICY ‘Novel features’ -Dr. B. R. Ambedkar ‘Conscience of Constitution’ - Granville Austin • Part IV • Art. 36 to 51 • Borrowed from Irish constitution of 1937 Spanish constitution State – Art . 36 Government & Parliament of India + Govt & Legislature of states + Local authorities + statutory authorities + bodies LIC, ONGC, SAIL + Private body working an instrument of State CCE-PDPU http://www.pdpu.ac.in/ VenkataKrishnan Source: Laxmikanth FEATURES OF DIRECTIVE PRINCIPLES – Fundamental in governance • Ideals state should keep in mind while formulating policies and enacting laws • Constitutional instructions [Resembles GoI Act, 1935, ONLY to GG or Governor] /recommendation to legislative/executive/administrative • Economic, Social & Political program • To establish Economic & Social democracy • Non – justiciable but, help courts in examining & determining validity of Law • Classification – NOT in constitution - 3 CCE-PDPU http://www.pdpu.ac.in/ VenkataKrishnan Source: Laxmikanth SOCIALISTIC PRINICIPLES Aim to democratic socialistic state & socio- economic justice Art 38 To minimize inequalities in income, status, facilities & opportunities. Art 39 Adequate means of livelihood, equitable distribution of material resources, prevention of concentration of wealth & means of production, equal pay, preservation of health & strength of workers & children against forcible abuse , opportunities for healthy development of children. Art 39 A Equal justice & free legal aid. CCE-PDPU http://www.pdpu.ac.in/ VenkataKrishnan -

Directive Principles of State Policy (Article 36 to 51)

COMMONWEALTH PARLIAMENTARY ASSOCIATION Directive Principles of State Policy (Article 36 to 51) Compilid and Edited by : Dr. ANANT KALSE Principal Secretary Maharashtra Legislature Secretariat & Secretary, Commonwealth Parliamentary Association, Maharashtra Branch * MAHARASHTRA LEGISLATURE SECRETARIAT VIDHAN BHAVAN, MUMBAI / NAGPUR JANUARY 2017 Directive Principles of State Policy (Article 36 to 51) Compiled and Edited by : Dr. ANANT KALSE Principal Secretary Maharashtra Legislature Secretariat & Secretary, Commonwealth Parliamentary Association, Maharashtra Branch Vidhan Bhavan, Mumbai * MAHARASHTRA LEGISLATURE SECRETARIAT VIDHAN BHAVAN, MUMBAI / NAGPUR JANUARY 2017 Hb 2369--1 FOREWORD An attempt is being made to provide a glimpse of Directive Principles of State Policy. I hope this will help the Law students and Officials of this Secretariat to understand the Constitutional Law. I am also very much indebted to Hon. Shri Ramraje Naik-Nimbalkar, Chairman, Maharashtra Legislative Council, Hon. Shri Haribhau Bagade, Speaker, Maharashtra Legislative Assembly and Hon. Shri Manikrao Thakre, Deputy Chairman, Maharashtra Legislative Council for their continuous support and motivation in accomplishing this task. I hope this brief compilation will be useful to the Law students. Vidhan Bhavan:Mumbai, Dr. ANANT KALSE, 25th January, 2017. Principal Secretary, Maharashtra Legislature Secretariat & Secretary, Commonwealth Parliamentary Association, Maharashtra Branch. Hb 2369--1a 1 DIRECTIVE PRINCIPLES OF STATE POLICY Introduction (1) The Directive Principles of State Policy are the guidelines or principles given to the central and State Governments of India, to be kept in mind while framing laws and policies. These provisions, contained in Part IV (Article 36-51) of the Constitution of India, are not enforceable by any court, but the principles laid down therein are considered fundamental in the governance of the country, making it the duty of the State[1] to apply these principles in making laws to establish a just society in the country.