Editorial by Paul E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monthly Forecast

May 2021 Monthly Forecast 1 Overview Overview 2 In Hindsight: Is There a Single Right Formula for In May, China will have the presidency of the Secu- Da’esh/ISIL (UNITAD) is also anticipated. the Arria Format? rity Council. The Council will continue to meet Other Middle East issues include meetings on: 4 Status Update since our virtually, although members may consider holding • Syria, the monthly briefings on political and April Forecast a small number of in-person meetings later in the humanitarian issues and the use of chemical 5 Peacekeeping month depending on COVID-19 conditions. weapons; China has chosen to initiate three signature • Lebanon, on the implementation of resolution 7 Yemen events in May. Early in the month, it will hold 1559 (2004), which called for the disarma- 8 Bosnia and a high-level briefing on Upholding“ multilateral- ment of all militias and the extension of gov- Herzegovina ism and the United Nations-centred internation- ernment control over all Lebanese territory; 9 Syria al system”. Wang Yi, China’s state councillor and • Yemen, the monthly meeting on recent 11 Libya minister for foreign affairs, is expected to chair developments; and 12 Upholding the meeting. Volkan Bozkir, the president of the • The Middle East (including the Palestinian Multilateralism and General Assembly, is expected to brief. Question), also the monthly meeting. the UN-Centred A high-level open debate on “Addressing the During the month, the Council is planning to International System root causes of conflict while promoting post- vote on a draft resolution to renew the South Sudan 13 Iraq pandemic recovery in Africa” is planned. -

LIST of PARTICIPANTS LISTE DES PARTICIPANTS 206Th Session of the Governing Council

LIST OF PARTICIPANTS LISTE DES PARTICIPANTS 206th Session of the Governing Council (extraordinary virtual session) 1 to 4 November 2020 - 2 - Mr./M. Chen Guomin Acting President of the Inter-Parliamentary Union Président par intérim de l'Union interparlementaire Mr./M. Martin Chungong Secretary General of the Inter-Parliamentary Union Secrétaire général de l'Union interparlementaire - 3 - AFGHANISTAN RAHMANI, Mir Rahman (Mr.) Speaker of the House of the People Governing Council Member EZEDYAR, Mohammad Alam (Mr.) Deputy Speaker of the House of Elders Governing Council Member of the Committee on Provincial Councils, Member Immunities and Privileges ELHAM KHALILI, Khadija (Ms.) Member of the House of the People Governing Council Member ARYUBI, Abdul Qader (Mr.) Secretary General, House of the People HASSAS, Pamir (Mr.) Director of Relations to the IPU, House Secretary of the Group of the People ALGERIA – ALGÉRIE CHENINE, Slimane (M.) Président de l'Assemblée populaire nationale Governing Council Member BOUZEKRI, Hamid (M.) Membre du Conseil de la Nation Governing Council Member LABIDI, Nadia (Mme) Membre de l'Assemblée populaire nationale Governing Council Member ANDORRA – ANDORRE SUÑÉ, Roser (Ms.) Speaker of Parliament Governing Council Member COSTA, Ferran (Mr.) Member of the Parliament Governing Council Member of the Finance and Budget Committee Member Chair of the Education, Research, Culture, Youth and Sport Committee VELA, Susanna (Ms.) Member of Parliament Governing Council Member of the Health Committee Member Member of the Education, -

Tracking Conflict Worldwide

CRISISWATCH Tracking Conflict Worldwide CrisisWatch is our global conict tracker, a tool designed to help decision-makers prevent deadly violence by keeping them up-to-date with developments in over 70 conicts and crises, identifying trends and alerting them to risks of escalation and opportunities to advance peace. Learn more about CrisisWatch July 2021 Global Overview JULY 2021 Trends for Last Month July 2021 Outlook for This Month DETERIORATED SITUATIONS August 2021 Ethiopia, South Africa, Zambia, CONFLICT RISK ALERTS Afghanistan, Bosnia And Herzegovina, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Ukraine, Ethiopia, Zambia, Armenia, Azerbaijan Cuba, Haiti, Syria, Tunisia RESOLUTION OPPORTUNITIES IMPROVED SITUATIONS None Central African Republic, Côte d’Ivoire CrisisWatch warns of three conict risks in August. Ethiopia’s spreading Tigray war is spiraling into a dangerous new phase, which will likely lead to more deadly violence and far greater instability countrywide. Fighting along the state border between Armenia and Azerbaijan, the deadliest since the Autumn 2020 war, could escalate further. More violence could surge in Zambia as tensions between ruling party and opposition supporters are running high ahead of the 12 August general elections. Our monthly conict tracker highlights deteriorations in thirteen countries in July. The Taliban continued its major offensive in Afghanistan, seizing more international border crossings and launching its rst assault on Kandahar city since 2001. South Africa faced its most violent unrest since apartheid ended in 1991, leaving over 300 dead. The killing of President Jovenel Moïse in murky circumstances plunged Haiti into political turmoil. Tunisia’s months-long political crisis escalated when President Kaïs Saïed dismissed Prime Minister Hichem Mechichi and suspended parliament. -

General Assembly Distr.: General 22 February 2010

United Nations A/HRC/WG.6/8/LSO/1 General Assembly Distr.: General 22 February 2010 Original: English Human Rights Council Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review Eighth session Geneva, 3–14 May 2010 National report submitted in accordance with paragraph 15 (a) of the annex to Human Rights Council resolution 5/1* Lesotho * The present document was not edited before being sent to the United Nations translation services. GE.10-11075 A/HRC/WG.6/8/LSO/1 I. Methodology and consultation process 1. The methodology used in compiling this Report is a combination of desk research and stakeholder consultations through a series of workshops. The Human Rights Unit of the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights first developed a framework for the compilation of the Report. That was followed by consultative workshop held with all Government Ministries. A National workshop involving all stakeholders was then held to complement and validate the draft Report. II. Background: Normative and institutional framework A. Background (a) Geography 2. Lesotho is located in Southern Africa. It is landlocked and entirely surrounded by the Republic of South Africa. It covers an area of about 30555 square kilometres and has a population of about 1.88 million.1 (b) Political system 3. Lesotho is a constitutional monarchy. It gained independence from Britain on the 4th October, 1966. The King is the Head of State. There are three arms of Government, namely, the Executive, the Legislature and the Judiciary, to ensure checks and balances. The Head of Government is the Prime Minister. 4. Over the years, Lesotho’s democracy has been evolving and at times proved to be fragile. -

International Experience with E-Voting

International Experience with E-Voting Norwegian E-Vote Project Jordi Barrat i Esteve, Ben Goldsmith and John Turner June 2012 TION FO DA R N EL U E O C F I T O L R A F A N L O S I Y T E S A Global Expertise. Local Solutions. T N E R M E S Sustainable Democracy. S T N I 2 5 Y E A R S International Experience with E-Voting Copyright © 2012 International Foundation for Electoral Systems. All rights reserved. Permission Statement: No part of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without the written permission of IFES. Requests for permission should include the following information: A description of the material for which permission to copy is desired. The purpose for which the copied material will be used and the manner in which it will be used. Your name, title, company or organization name, telephone number, fax number, email address and mailing address. Please send all requests for permission to: International Foundation for Electoral Systems 1850 K Street, NW, Fifth Floor Washington, DC 20006 Email: [email protected] Fax: 202.350.6701 International Experience with E-voting Norwegian E-vote Project International Experience with E-voting Norwegian E-vote Project Jordi Barrat i Esteve, Ben Goldsmith and John Turner June 2012 Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Foundation for Electoral Systems. -

Parliamentary Oversight of European Security and Defence Policy: a Matter of Formal Competences Or the Will of Parliamentarians?

Online Papers on Parliamentary Democracy 4/2016 Parliamentary Oversight of European Security and Defence Policy: A Matter of Formal Competences or the Will of Parliamentarians? Aleksandra Maatsch, Patricio Galella This online paper series is published by PADEMIA: Parliamentary Democracy in Europe It is funded by the European Commission. Series Editors: Thomas Christiansen, Anna Herranz, Anna-Lena Högenauer ISBN: 978-94-91704-13-0 Parliamentary Oversight of European Security and Defence Policy: A Matter of Formal Competences or the Will of Parliamentarians? Aleksandra Maatsch, Patricio Galella 1 Abstract Are parliaments with strong formal powers for the deployment of troops likely to conduct more intensive oversight than their counterparts with weak or no powers? The literature suggests that strong formal powers delineate boundaries of parliamentary oversight. However, this article demonstrates that strong formal powers are not necessary for parliaments in order to conduct oversight. If parliaments with weak formal powers had strong incentives to carry out oversight of the EU NAVFOR Operation Atalanta, they did so by means of weakly-regulated forms of oversight. The article demonstrates that oversight beyond mandatory procedures coincides with domestic politicisation of Operation Atalanta (national framing). However, if European or international frames were dominant, parliaments were more likely to limit their oversight to mandatory procedures. Cases selected for the analysis, namely Germany, UK, France, Spain and Luxembourg, vary on the two explanatory factors (strength of formal powers and domestic politicisation of the Operation). 1 Aleksandra Maatsch, Chair of European and Multilevel Politics at the University of Cologne (Interim), Patricio Galella is a lawyer and holds a PhD in International Law and International Relations (University Complutense of Madrid, Spain). -

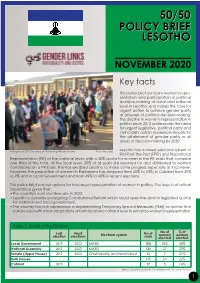

2020 Policy Brief

50/5050/50 POLICY BRIEF LESOTHO NOVEMBER 2020 Key facts This policy brief concerns women's repre- sentation and participation in political decision-making at local and national level in Lesotho, and makes the case for urgent action to achieve gender parity at all levels of political decision-making. The decline in women's representation in politics since 2012 underscores the need for urgent legislative, political party and civil society action as pressure mounts for the attainment of gender parity in all areas of decision-making by 2030. Voting in the 2017 elections at Malumeng Primary School, Photo: Ntolo Lekau Lesotho has a mixed electoral system of First-Past-The-Post (FPTP) and Proportional Representation (PR) at the national level, with a 30% quota for women in the PR seats that comprise one third of the total. At the local level, 30% of all seats are reserved for and distributed to women candidates on a PR basis. This has enabled Lesotho to make some progress especially at local level. However, the proportion of women in Parliament has dropped from 25% to 23%; in Cabinet from 29% to 9% and in Local Government and from 49% to 40% in recent elections. This policy brief sets out options for increased representation of women in politics. The issue is of critical importance given that: • The country's next elections are in 2022. •Lesotho is currently undergoing Constitutional Reform which could open the door to legislated quotas for national and local government. •The country has rich experience in implementing Temporary Special Measures (TSM) or quotas that can be used with minor adaptations at both local and national level to enhance women's representation. -

Gender Equality and Women's Empowerment

ACADEMIC PAPER GENDER EQUALITY AND WOMEN’S EMPOWERMENT: CONSTITUTIONAL JURISPRUDENCE MAY 2017 UN WOMEN © 2017 UN Women The electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribute- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information on this licence see: <http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/>. This publication is independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of UN Women, the Just Governance Group or International IDEA, or the view of their respective Boards or Council members. ACADEMIC PAPER GENDER EQUALITY AND WOMEN’S EMPOWERMENT: CONSTITUTIONAL JURISPRUDENCE UN WOMEN NEW YORK, MAY 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ...................................................... 7 Abbreviations ......................................................... 10 Executive Summary .................................................... 11 Recommendations. 11 Constitutional provisions .................................... 11 CEDAW and international instruments ......................... 12 Judicial reasoning ........................................... 12 Public-interest litigation approaches .......................... 12 Addressing gaps through further research. 12 1. Introduction -

Unicef Somalia

UNICEF SOMALIA EMERGENCY COUNTRY PROFILE May 1999 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY OF BASIC DATA............................................................................................................1 PART 1: BACKGROUND..................................................................................................................4 A) SOCIO-POLITICAL CONTEXT...............................................................4 B) CURRENT SITUATION...........................................................................9 C) SECURITY............................................................................................11 D) SITUATION OF WOMEN AND CHILDREN...........................................13 PART II: UNICEF EMERGENCY PROGRAMME IN SOMALIA.......................................................16 HEALTH ....................................................................................................16 WATER AND SANITATION.......................................................................17 BASIC EDUCATION.................................................................................18 COORDINATION, COMMUNICATION AND ADVOCACY .........................20 EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS AND RESPONSE ................................21 STAFF.......................................................................................................23 FUNDING .................................................................................................24 COOPERATION WITH UN/NGOs/ INTERNATIONAL ORGANISATIONS .......................................................24 -

Final List of Delegations

Supplément au Compte rendu provisoire (21 juin 2019) LISTE FINALE DES DÉLÉGATIONS Conférence internationale du Travail 108e session, Genève Supplement to the Provisional Record (21 June 2019) FINAL LIST OF DELEGATIONS International Labour Conference 108th Session, Geneva Suplemento de Actas Provisionales (21 de junio de 2019) LISTA FINAL DE DELEGACIONES Conferencia Internacional del Trabajo 108.ª reunión, Ginebra 2019 La liste des délégations est présentée sous une forme trilingue. Elle contient d’abord les délégations des Etats membres de l’Organisation représentées à la Conférence dans l’ordre alphabétique selon le nom en français des Etats. Figurent ensuite les représentants des observateurs, des organisations intergouvernementales et des organisations internationales non gouvernementales invitées à la Conférence. Les noms des pays ou des organisations sont donnés en français, en anglais et en espagnol. Toute autre information (titres et fonctions des participants) est indiquée dans une seule de ces langues: celle choisie par le pays ou l’organisation pour ses communications officielles avec l’OIT. Les noms, titres et qualités figurant dans la liste finale des délégations correspondent aux indications fournies dans les pouvoirs officiels reçus au jeudi 20 juin 2019 à 17H00. The list of delegations is presented in trilingual form. It contains the delegations of ILO member States represented at the Conference in the French alphabetical order, followed by the representatives of the observers, intergovernmental organizations and international non- governmental organizations invited to the Conference. The names of the countries and organizations are given in French, English and Spanish. Any other information (titles and functions of participants) is given in only one of these languages: the one chosen by the country or organization for their official communications with the ILO. -

1 Rev. 7 Project Name Support to Building Inclusive Institutions Of

SOMALIA UN MPTF PROGRAMME QUARTERLY PROGRESS REPORT Period (Quarter-Year): Period: Quarter-2 (April- June) 2017 Project Name Support to Building Inclusive Institutions of Parliament in Somalia (PSP) (UNDP SOM10 Project ID 00094911) Gateway ID MPTF Project ID-00096825 (Gateway ID) Start date March 2013 Planned end date 30 Jun 2017 Name: Nahid Hussein Focal Person Email: [email protected] (Tel): 252 (0)612863045 PSG PSG (s): 1: Inclusive politics: Achieve a stable and peaceful Somalia through inclusive political processes Priority Priority 1: Advance inclusive political dialogue to clarify and settle relations between the federal government and existing and emerging administrations and initiate processes of social reconciliation to restore between communities. Milestone Location Federal; Somaliland; Puntland, Galmudug, Jubaland, Southwest, and Hirshabelle states Gender Marker 2 Total Budget as per ProDoc USD 16,617,286 MPTF: USD 4,427,882 PBF: 0 Non MPTF sources: UNDP Trac: USD 3,918,619 Other: USD 8,290,236 PUNO Report approved by: Position/Title Signature 1. PSG1 David Akopyan Deputy Country Director – (4SOU1) Programme 1 Rev. 7 SOMALIA UN MPTF Total MPTF Funds Received Total non-MPTF Funds Received PUNO Current quarter Cumulative Current quarter Cumulative UNDP 563,628 4,427,882 0 12,208,855 JP Expenditure of MPTF Funds1 JP Expenditure of non-MPTF Funds PUNO Current quarter Cumulative Current quarter Cumulative UNDP 276,749 2,879,879 940,033 11,758,921 QUARTER HIGHLIGHTS 1. The first annual Somali Women Parliamentarian conference was held in Mogadishu on 24-25 April 2017 2. Capacity building activities provided to the five parliaments namely NFP, SWSA, HSSA, JSA, PL HoR by the project include training on legislative process, committee functions, consultations and civic education. -

A STUDY of the LEGAL Fralyiework of PROTECTING COPYRIGHTS in HARGEISA REGION of SDMALILAND

A STUDY OF THE LEGAL FRAlYIEWORK OF PROTECTING COPYRIGHTS IN HARGEISA REGION OF SDMALILAND A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED FOR THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF A MASTER OF LAW OF KAMPAVt INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY MASTER OF COMMERCIAL LAW BY: !VIULAHO MOHAMED ALI Reg No: LLM-CL/45563/143/DF SUPERVISOR DR MUGAGGA ROBERT NOVEMBER 2015 DECLARATION A "This thesis is my original work and has not been presented for Degree or any other academic award in University or Institution of Learning". Mulaho Mohamed Ali Name and Signature of Candidate Date---lfljJ.-----#-(If I '}$J ;- DECLARATION B "I confinn that the work reported in this thesis is carried out by the candidate under my supervision." oate----- _\':~J~-- ~-- --- ii APPROVAL SHEET This Dissertation is entitled "A Study of the Legal Framework of Protecting Copyrights in Hargeisa Region of Somaliland" prepared and submitted by Mulaho Mohamed Ali in partial fulfillment for the requirements for award of a Master of Commercial Law has been examined and approved by iii DEDICATION This research is dedicated to my beloved Parents Dr. Mohamed Ali Odey, Mrs Baarliin Mohamed Bahdoon and Mrs Luul Mohamud Hirabe as well as all my siblings particularly Ali Mohamed Ali Odey and Liiban Mohamed Ali Odey those who have always been there for me whenever I needed their help. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like thanks to the Almighty Allah for all time protecting and guiding me since early childhood up to now, and allow me to complete this study Special thanks to my supervisor Dr. Mugagga Robert who guided and advised me while carrying out this study.