Legal Environment Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Combined Seventeenth to Twenty-Second Periodic Reports Submitted by Botswana Under Article 9 of the Convention, Due Since 2009*

United Nations CERD/C/BWA/17-22 International Convention on Distr.: General 21 July 2020 the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination Original: English English, French and Spanish only Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination Combined seventeenth to twenty-second periodic reports submitted by Botswana under article 9 of the Convention, due since 2009* [Date received: 30 January 2020] * The present document is being issued without formal editing. GE.20-09810(E) CERD/C/BWA/17-22 General Information Replies to the list of issues prior to reporting CERD/C/BWA/QPR/17-22 Reply to paragraph 1 of the list of issues 1. In Botswana, the primary legislation that offers protection to human rights covered by the Convention is the Constitution. Section 3 of the Constitution accords fundamental rights and freedoms to every person on a non-discriminatory basis, including race. In addition, Section 15 of the Constitution specifically prohibits discrimination on the basis of, among others, race. 2. Since Botswana’s last report, significant legislative developments which promote and protect human rights covered by this Convention have taken place. These include the enactment of the Local Government Act of 2008, Cybercrime and Computer Related Crimes Act of 2018 and the Children’s Act of 2009. These laws incorporate the principle of non-discrimination on the basis of race in public procurement, transmission of electronic material and administration of the Children’s Act, respectively. 3. In terms of institutional framework, the Government has established a Human Rights Unit within the Ministry of Presidential Affairs, Governance and Public Administration. -

The Case of Botswana

BIDPA Publications Series BIDPA Working Paper 45 Synthetic Gem QualityOctober 2016 Diamonds and their Potential Impact on the Botswana Economy Technology and the Nature of Active Citizenship: The Case of Botswana Roman Grynberg Margaret Sengwaketse MolefeMasedi B. Motswapong Phirinyane Botswana Institute for Development Policy Analysis BOTSWANA INSTITUTE FOR DEVELOPMENT POLICY ANALYSIS Synthetic Gem Quality Diamonds and their Potential Impact on the Botswana Economy BIDPA The Botswana Institute for Development Policy Analysis (BIDPA) is an independent trust, which started operations in 1995 as a non-governmental policy research institution. BIDPA’s mission is to inform policy and build capacity through research and consultancy services. BIDPA is part-funded by the Government of Botswana. BIDPA Working Paper Series The series comprises of papers which reflect work in progress, which may be of interest to researchers and policy makers, or of a public education character. Working papers may already be published elsewhere or may appear in other publications. Molefe B. Phirinyane is Research Fellow at the Botswana Institute for Development Policy Analysis. ISBN: 978-99968-451-3-0 © Botswana Institute for Development Policy Analysis, 2016 Disclaimer The views expressed in this document are entirely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of BIDPA. Technology and the Nature of Active Citizenship: The Case of Botswana TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ...................................................................................................................... -

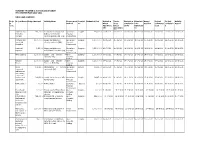

MINISTRY of DEFENCE JUSTICE and SECURITY PROCUREMEN PLAN 2021-2022 MDJS HEADQUARTERS Proje Ct Code Project Name Budget Amount Ac

MINISTRY OF DEFENCE JUSTICE AND SECURITY PROCUREMEN PLAN 2021-2022 MDJS HEADQUARTERS Proje Project Name Budget Amount Activity Name Procurement Descipli Estimated Cost Invitation Tender Evaluation Submissio Award Project Project Activity ct Method ne Direct Close completion n for Decision Commence Completio Report Code Appointme Direct by PE Adjudicati ment n ntte Appointme on ntte Uniforms and 143,230.00 A Contract for Supply and Quotations Supplies 143,230.00 20-04-2021 08-05-2021 08-04-2021 04-12-2021 15-06-2021 15-06-2021 22-06-2021 26-08-2021 Protective Delivery of Protective Proposal Clothing Clothing and Uniform (HQ) Procurement Domestic and 1,500,000.00 Supply and delivery of Quotations Supplies 1,500,000.00 16-08-2021 31-08-2021 31-08-2021 09-06-2021 15-06-2021 15-06-2021 22-06-2021 26-08-2021 household cleaning materials (HQ) Proposal Requisites Procurement Incidental 2,350,000 Supply and delivery of Quotations Supplies 2,350,000.00 16-07-2021 08-03-2021 08-05-2021 08-09-2021 08-12-2021 16-08-2021 20-08-2021 23-08-2021 Expenses Refreshments for MDJS (HQ) Proposal Procurement Office supplies 1,500,000.00 Supply and Delivery of Open Supplies 1,500,000.00 14-06-2021 07-09-2021 14-07-2021 23-07-2021 29-07-2021 08-02-2021 23-08-2021 27-08-2021 Sationery (HQ) Domestic Bidding Genuine 1,500,000.00 Supply and Delivery of Open Supplies 1,500,000.00 14-06-2021 07-09-2021 14-07-2021 23-07-2021 29-07-2021 08-02-2021 23-08-2021 27-08-2021 Toners Toners to MDJS HQ Domestic Bidding Office 172,110.00 Maintanance of running Quotations Service -

Tender Advert

TENDER ADVERT www.etender.co.bw Botswana Prison Service - DJS/MTC/PRI 031/2020/2021 Companies are invited to express their interest in the consultancy services on conditions of service for non-uniformed (civilian) staff of the Botswana Prison Service Closing: 21 January 2021 09H00 Site Visit: Contacts Senior Superintendent Ntshebe 3611711/21 3975398/003 [email protected] Senior Superintendent Bedi 3611711/21 3975398/003 [email protected] Collection : The physical address for the collection of Tender Document is Botswana Prison Service Headquarters, Broadhurst Industrial, Plot No. 10211, next to Mafulo House at the Supplies Office. Documents may be collected during office days between 07:30 and 12:45 and from 13:45 to 16:30 with effect from 14th December 2020. Queries relating to the issuance of these documents may be addressed to: Senior Superintendent Ntshebe and Senior Superintendent Bedi at Telephone No. 3611711/21, Fax Nos. 3975398/003, Email: [email protected] and [email protected] Fee: Delivery: The names and addresses of companies should be clearly marked on the envelope. One (1) original marked “Original” plus two (2) copies marked “Copy” must be hand-delivered in sealed envelopes. Identification details to be shown on each tender offer are: “Tender No. DJS/MTC/PRI 031/2020/2021 - Expression of Interest for Consultancy Services on Conditions of Service for Non-Uniformed (Civilian) Staff of the Botswana Prison Service”. Tender offers will be submitted to The Secretary, Ministerial Tender Committee, Ministry of Defence, Justice and Security Headquarters, Central Square Building, Ground Floor, Office No. 004 at the Tender Opening Hall, Gaborone, Central Business District, Phase 2, Plot No. -

Republic of Botswana - European Community

Republic of Botswana - European Community JOINT ANNUAL REPORT 2008 Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................... 3 1. Country Performance ..................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Update on the political situation and political governance ................................................................. 4 1.2 Update on the economic situation and economic governance............................................................. 6 1.3 Update on the poverty and social situation......................................................................................... 10 1.4 Update on the environmental situation............................................................................................... 12 2. Overview of past and ongoing co-operation................................................................................................. 13 2.1 Reporting on the financial performance of EDF resources............................................................... 13 2.2 Reporting on General and Sector Budget Support............................................................................ 14 2.3 Project and programmes in the focal and non-focal areas................................................................ 15 2.3.1 Focal Sector: Human Resource Development......................................................................... -

The Republic of Botswana Second and Third Report To

THE REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA SECOND AND THIRD REPORT TO THE AFRICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN AND PEOPLES' RIGHTS (ACHPR) IMPLEMENTATION OF THE AFRICAN CHARTER ON HUMAN AND PEOPLES’ RIGHTS 2015 1 | P a g e TABLE OF CONTENTS I. PART I. a. Abbreviations b. Introduction c. Methodology and Consultation Process II. PART II. A. General Information - B. Laws, policies and (institutional) mechanisms for human rights C. Follow-up to the 2010 Concluding observations D. Obstacles to the exercise and enjoyment of the rights and liberties enshrined in the African Charter: III. PART III A. Areas where Botswana has made significant progress in the realization of the rights and liberties enshrined in the African Charter a. Article 2, 3 and 19 (Non-discrimination and Equality) b. Article 7 & 26 (Fair trial, Independence of the Judiciary) c. Article 10 (Right to association) d. Article 14 (Property) e. Article 16 (Health) f. Article 17 (Education) g. Article 24 (Environment) B. Areas where some progress has been made by Botswana in the realization of the rights and liberties enshrined in the African Charter a. Article 1er (implementation of the provisions of the African Charter) b. Article 4 (Life and Integrity of the person) c. Article 5 (Human dignity/Torture) d. Article 9 (Freedom of Information) e. Article 11 (Freedom of Assembly) f. Article 12 (Freedom of movement) g. Article 13 (participation to public affairs) h. Article 15 (Work) i. Article 18 (Family) j. Article 20 (Right to existence) k. Article 21 (Right to freely dispose of wealth and natural resources) 2 | P a g e C. -

Botswana North-South Carrier Water Project Field Survey

Botswana North-South Carrier Water Project Field Survey: July 2003 1. Project Profile & Japan’s ODA Loan Angola Zambia Botswana Zimbabwe Namibia Maun Francistown Ghanzi Palapye Mamuno Maharapye South Africa Gaborone Tshabong Project location map Mmamashia Water Treatment Works 1.1 Background Botswana is a landlocked country that is situated in the Kalahari Basin on the plains of southern Africa (average altitude: approximately 900 meters); it is bordered by the Republic of South Africa, Zimbabwe, Namibia, and Zambia. Its territory is generally flat and covers an area of 582 thousand square meters or approximately one-and-a-half times the size of Japan. It has a sub-tropical climate, with much of the country being arid or semi-arid. Annual rainfall averages 400mm nationwide, with southwestern regions seeing the least precipitation (250mm) and southeastern areas the most (600mm). Rainfall levels are seasonally affected and unstable. Botswana has few surface water resources in consequence of its topographical and geographical features and sources the majority of its water from groundwater fossil resources. At the time of appraisal, the water supply rate was 100 percent in urban areas centered around the capital, Gaborone, but in view of the fact that demand was growing at exponential rates, large-scale development of underground water was problematic and water resources around the capital had been developed, the country was considering water transmission from other regions. In addition, Gaborone was importing water on a regular basis from South Africa and the country harbored a long-cherished wish to develop independent national water resources. By contrast, the water supply rate in the regions was 50 percent and reliant on groundwater. -

Botswana Country Report-Annex-4 4Th Interim Techical Report

PROMOTING PARTNERSHIPS FOR CRIMEPREVENTION BETWEEN THE STATE AND PRIVATE SECURITY PROVIDERS IN BOTSWANA BY MPHO MOLOMO AND ZIBANI MAUNDENI Introduction Botswana stands out as the only African country to have sustained an unbroken record of liberal democracy and political stability since independence. The country has been dubbed the ‘African Miracle’ (Thumberg Hartland, 1978; Samatar, 1999). It is widely regarded as a success story arising from its exploitation and utilisation of natural resources, establishing a strong state, institutional and administrative capacity, prudent macro-economic stability and strong political leadership. These attributes, together with the careful blending of traditional and modern institutions have afforded Botswana a rare opportunity of political stability in the Africa region characterised by political and social strife. The expectation is that the economic growth will bring about development and security. However, a critical analysis of Botswana’s development trajectory indicates that the country’s prosperity has it attendant problems of poverty, unemployment, inequalities and crime. Historically crime prevention was a preserve of the state using state security agencies as the police, military, prisons and other state apparatus, such as, the courts and laws. However, since the late 1980s with the expanded definition of security from the narrow static conception to include human security, it has become apparent that state agencies alone cannot combat the rising levels of crime. The police in recognising that alone they cannot cope with the crime levels have been innovative and embarked on other models of public policing, such as, community policing as a public society partnership to combat crime. To further cater for the huge demand on policing, other actors, which are non-state actors; in particular private security firms have come in, especially in the urban market and occupy a special niche to provide a service to those who can afford to pay for it. -

Securing Recognition of Minorities and Maginalized People and Their Rights in Botswana

Evaluation: Securing Recognition of Minorities and Marginalized People and their Rights in Botswana PROJECT EVALUATION REPORT FINAL SECURING RECOGNITION OF MINORITIES AND MAGINALIZED PEOPLE AND THEIR RIGHTS IN BOTSWANA Submitted to: Minorities Rights Group International, 54 Commercial Street, London E1, 6LT, United Kingdom Submitted by: Tersara Investments P.O. Box 2139, Gaborone, Botswana, Africa 2/27/2019 This document is property of Minorities Rights Group International, a registered UK Charity and Company Limited by Guarantee and its Partners. 1 Evaluation: Securing Recognition of Minorities and Marginalized People and their Rights in Botswana Document details Client Minority Rights Group International Project title Consulting Services for the Final Evaluation: Securing Recognition of Minorities and Marginalized Peoples and their Rights in Botswana Document type Final Evaluation Document No. TS/18/MRG/EVAL00 This document Text (pgs.) Tables (No.) Figures (no.) Annexes Others comprises 17 3 7 2 N/A Document control Document version Detail Issue date TS/19/MRG/EVAL01 Project Evaluation Report FINAL for 13 June 2019 MRGI 2 Evaluation: Securing Recognition of Minorities and Marginalized People and their Rights in Botswana Contents Document details ..................................................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. Document control ................................................................................................................................... 2 LIST OF FIGURES (TABLES, CHARTS) -

State of the Nation Address to the 3Rd Session of the 10Th Parliament

State of the Nation Address to the 3rd Session of the 10th Parliament 08/11/11 State of the Nation Address to the 3rd Session of the 10th Parliament State of the Nation Address to the 3rd Session of the 10th Parliament STATE OF THE NATION ADDRESS BY HIS EXCELLENCY Lt. GEN. SERETSE KHAMA IAN KHAMA PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA TO THE THIRD SESSION OF THE TENTH PARLIAMENT "BOTSWANA FIRST" 7th November 2011, GABORONE: 1. Madam Speaker, before we begin, I request that we all observe a moment of silence for those who have departed during the past year. Thank you. 2. Let me also take this opportunity to commend the Leader of the House, His Honour the Vice President, on his recent well deserved awards. In addition to the Naledi ya Botswana, which he received for his illustrious service to the nation, His Honour also did us proud when he received a World Citizen Award for his international, as well as domestic, contributions. I am sure other members will agree with me that these awards are deserving recognition of a true statesman. 3. Madam Speaker, it is a renewed privilege to address this Honourable House and the nation. This annual occasion allows us to step back and take a broader look at the critical challenges we face, along with the opportunities we can all embrace when we put the interests of our country first. 4. As I once more appear before you, I am mindful of the fact that this address will be the subject of further deliberations. -

Department of Road Transport and Safety Offices

DEPARTMENT OF ROAD TRANSPORT AND SAFETY OFFICES AND SERVICES MOLEPOLOLE • Registration & Licensing of vehicles and drivers • Driver Examination (Theory & Practical Tests) • Transport Inspectorate Tel: 5920148 Fax: 5910620 P/Bag 52 Molepolole Next to Molepolole Police MOCHUDI • Registration & Licensing of vehicles and drivers • Driver Examination (Theory & Practical Tests) • Transport Inspectorate P/Bag 36 Mochudi Tel : 5777127 Fax : 5748542 White House GABORONE Headquarters BBS Mall Plot no 53796 Tshomarelo House (Botswana Savings Bank) 1st, 2nd &3rd Floor Corner Lekgarapa/Letswai Road •Registration & Licensing of vehicles and drivers •Road safety (Public Education) Tel: 3688600/62 Fax : Fax: 3904067 P/Bag 0054 Gaborone GABORONE VTS – MARUAPULA • Registration & Licensing of vehicles and drivers • Driver Examination (Theory & Practical Tests) • Vehicle Examination Tel: 3912674/2259 P/Bag BR 318 B/Hurst Near Roads Training & Roads Maintenance behind Maruapula Flats GABORONE II – FAIRGROUNDS • Registration & Licensing of vehicles and drivers • Driver Examination : Theory Tel: 3190214/3911540/3911994 Fax : P/Bag 0054 Gaborone GABORONE - OLD SUPPLIES • Registration & Licensing of vehicles and drivers • Transport Permits • Transport Inspectorate Tel: 3905050 Fax :3932671 P/Bag 0054 Gaborone Plot 1221, Along Nkrumah Road, Near Botswana Power Corporation CHILDREN TRAFFIC SCHOOL •Road Safety Promotion for children only Tel: 3161851 P/Bag BR 318 B/Hurst RAMOTSWA •Registration & Licensing of vehicles and drivers •Driver Examination (Theory & Practical -

Chapter 1 Botswana.Fm

HUMAN RIGHTS PROTECTED? NINE SOUTHERN AFRICAN COUNTRY REPORTS ON HIV, AIDS AND THE LAW AIDS and Human Rights Research Unit 2007 Human rights protected? Nine Southern African country reports on HIV, AIDS and the law Published by: Pretoria University Law Press (PULP) The Pretoria University Law Press (PULP) is a publisher at the Faculty of Law, University of Pretoria, South Africa. PULP endeavours to publish and make available innovative, high-quality scholarly texts on law in Africa that have been peer-reviewed. PULP also publishes a series of collections of legal documents related to public law in Africa, as well as text books from African countries other than South Africa. For more information on PULP, see www.pulp.up.ac.za Printed and bound by: ABC Press Cape Town Cover design: Yolanda Booyzen, Centre for Human Rights To order, contact: PULP Faculty of Law University of Pretoria South Africa 0002 Tel: +27 12 420 4948 Fax: +27 12 362 5125 [email protected] www.pulp.up.ac.za ISBN: 978-0-9802658-7-3 The financial support of OSISA is gratefully acknowledged. © 2007 Copyright subsists in this work. It may be reproduced only with permission from the AIDS and Human Rights Research Unit, University of Pretoria. Table of contents PREFACE iv LIST OF FREQUENTLY USED ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS vii 1 HIV, AIDS and the law in Botswana 1 2 HIV, AIDS and the law in Lesotho 39 3 HIV, AIDS and the law in Malawi 81 4 HIV, AIDS and the law in Mozambique 131 5 HIV, AIDS and the law in Namibia 163 6 HIV, AIDS and the law in South Africa 205 7 HIV, AIDS and the