Reflections from the Developments of School Science Curricula

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

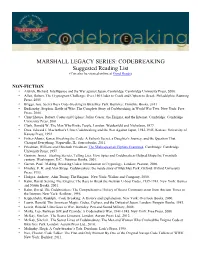

CODEBREAKING Suggested Reading List (Can Also Be Viewed Online at Good Reads)

MARSHALL LEGACY SERIES: CODEBREAKING Suggested Reading List (Can also be viewed online at Good Reads) NON-FICTION • Aldrich, Richard. Intelligence and the War against Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. • Allen, Robert. The Cryptogram Challenge: Over 150 Codes to Crack and Ciphers to Break. Philadelphia: Running Press, 2005 • Briggs, Asa. Secret Days Code-breaking in Bletchley Park. Barnsley: Frontline Books, 2011 • Budiansky, Stephen. Battle of Wits: The Complete Story of Codebreaking in World War Two. New York: Free Press, 2000. • Churchhouse, Robert. Codes and Ciphers: Julius Caesar, the Enigma, and the Internet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. • Clark, Ronald W. The Man Who Broke Purple. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1977. • Drea, Edward J. MacArthur's Ultra: Codebreaking and the War Against Japan, 1942-1945. Kansas: University of Kansas Press, 1992. • Fisher-Alaniz, Karen. Breaking the Code: A Father's Secret, a Daughter's Journey, and the Question That Changed Everything. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, 2011. • Friedman, William and Elizebeth Friedman. The Shakespearian Ciphers Examined. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1957. • Gannon, James. Stealing Secrets, Telling Lies: How Spies and Codebreakers Helped Shape the Twentieth century. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2001. • Garrett, Paul. Making, Breaking Codes: Introduction to Cryptology. London: Pearson, 2000. • Hinsley, F. H. and Alan Stripp. Codebreakers: the inside story of Bletchley Park. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993. • Hodges, Andrew. Alan Turing: The Enigma. New York: Walker and Company, 2000. • Kahn, David. Seizing The Enigma: The Race to Break the German U-boat Codes, 1939-1943. New York: Barnes and Noble Books, 2001. • Kahn, David. The Codebreakers: The Comprehensive History of Secret Communication from Ancient Times to the Internet. -

Benedict Cumberbatch Talks the Imitation Game

JANUARY 2015 | VOLUME 16 | NUMBER 1 Smart Meets Sexy BENEDICT CUMBERBATCH TALKS THE IMITATION GAME Inside HUGH BONNEVILLE LIAM NEESON PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 41619533 THE 10 INCREDIBLE MOVIES YOU HAVE TO SEE THIS YEAR, PAGE 26 CONTENTS JANUARY 2015 | VOL 16 | Nº1 COVER STORY 40 GENIUS ROLE Benedict Cumberbatch’s fervent fans won’t be disappointed with his latest role. The Imitation Game casts the 38-year-old Brit as Alan Turing, a gay, mathematical genius who helped hasten the end of WWII. Here he talks about bringing Turing to life and his various other talents BY INGRID RANDOJA REGULARS 4 EDITOR’S NOTE 8 SNAPS 10 IN BRIEF 14 SPOTLIGHT: CANADA 16 ALL DRESSED UP 20 IN THEATRES 44 CASTING CALL 47 RETURN ENGAGEMENT 48 AT HOME 50 FINALLY… FEATURES IMAGE HARGRAVE/AUGUST AUSTIN BY PHOTO COVER 26 2015’S BIG PICS! 32 FABLED CAST 34 MAN OF ACTION 38 PAPA BEAR It’s going to be an epic year We break down which famous Taken 3 star Liam Neeson Paddington’s Hugh Bonneville at the movies. We take you actors play which well-known talks about his longtime says playing father figure to a through the 10 films you must fairy tale characters in love of action movies, and mischievous talking bear gave see, starting with the return of the musical extravaganza recent decision to get clean him the chance to revisit his Star Wars! Into the Woods and healthy own childhood BY INGRID RANDOJA BY INGRID RANDOJA BY BOB STRAUSS BY INGRID RANDOJA JANUARY 2015 | CINEPLEX MAGAZINE | 3 EDITOR’S NOTE PUBLISHER SALAH BACHIR EDITOR MARNI WEISZ DEPUTY EDITOR INGRID RANDOJA ART DIRECTOR TREVOR THOMAS STEWART ASSISTANT ART DIRECTOR STEVIE SHIPMAN VICE PRESIDENT, PRODUCTION SHEILA GREGORY CONTRIBUTORS LEO ALEFOUNDER, BOB STRAUSS ADVERTISING SALES FOR CINEPLEX MAGAZINE AND LE MAGAZINE CINEPLEX IS HANDLED BY CINEPLEX MEDIA. -

Why Python for Chatbots

Schedule: 1. History of chatbots and Artificial Intelligence 2. The growing role of Chatbots in 2020 3. A hands on look at the A.I Chatbot learning sequence 4. Q & A Session Schedule: 1. History of chatbots and Artificial Intelligence 2. The growing role of Chatbots in 2020 3. A hands on look at the A.I Chatbot learning sequence 4. Q & A Session Image credit: Archivio GBB/Contrasto/Redux History •1940 – The Bombe •1948 – Turing Machine •1950 – Touring Test •1980 Zork •1990 – Loebner Prize Conversational Bots •Today – Siri, Alexa Google Assistant Image credit: Photo 172987631 © Pop Nukoonrat - Dreamstime.com 1940 Modern computer history begins with Language Analysis: “The Bombe” Breaking the code of the German Enigma Machine ENIGMA MACHINE THE BOMBE Enigma Machine image: Photographer: Timothy A. Clary/AFP The Bombe image: from movie set for The Imitation Game, The Weinstein Company 1948 – Alan Turing comes up with the concept of Turing Machine Image CC-BY-SA: Wikipedia, wvbailey 1948 – Alan Turing comes up with the concept of Turing Machine youtube.com/watch?v=dNRDvLACg5Q 1950 Imitation Game Image credit: Archivio GBB/Contrasto/Redux Zork 1980 Zork 1980 Text parsing Loebner Prize: Turing Test Competition bit.ly/loebnerP Conversational Chatbots you can try with your students bit.ly/MITsuku bit.ly/CLVbot What modern chatbots do •Convert speech to text •Categorise user input into categories they know •Analyse the emotion emotion in user input •Select from a range of available responses •Synthesize human language responses Image sources: Biglytics -

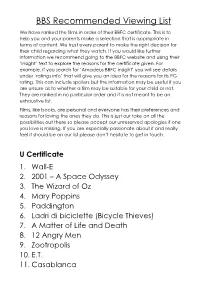

BBS Recommended Viewing List

BBS Recommended Viewing List We have ranked the films in order of their BBFC certificate. This is to help you and your parents make a selection that is appropriate in terms of content. We trust every parent to make the right decision for their child regarding what they watch. If you would like further information we recommend going to the BBFC website and using their ‘Insight’ text to explore the reasons for the certificate given. For example, if you search for ‘Amadeus BBFC insight’ you will see details under ‘ratings info’ that will give you an idea for the reasons for its PG rating. This can include spoilers but the information may be useful if you are unsure as to whether a film may be suitable for your child or not. They are ranked in no particular order and it is not meant to be an exhaustive list. Films, like books, are personal and everyone has their preferences and reasons for loving the ones they do. This is just our take on all the possibilities out there so please accept our unreserved apologies if one you love is missing. If you are especially passionate about it and really feel it should be on our list please don’t hesitate to get in touch. U Certificate 1. Wall-E 2. 2001 – A Space Odyssey 3. The Wizard of Oz 4. Mary Poppins 5. Paddington 6. Ladri di biciclette (Bicycle Thieves) 7. A Matter of Life and Death 8. 12 Angry Men 9. Zootropolis 10. E.T. 11. Casablanca 12. Sense and Sensibility 13. -

Inequality in 900 Popular Films: Gender, Race/Ethnicity, LGBT, & Disability from 2007‐2016

July 2017 INEQUALITY IN POPULAR FILMS MEDIA, DIVERSITY, & SOCIAL CHANGE INITIATIVE USC ANNENBERG MDSCInitiative Facebook.com/MDSCInitiative THE NEEDLE IS NOT MOVING ON SCREEN FOR FEMALES IN FILM Prevalence of female speaking characters across 900 films, in percentages Percentage of 900 films with 32.8 32.8 Balanced Casts 12% 29.9 30.3 31.4 31.4 28.4 29.2 28.1 Ratio of males to females 2.3 : 1 Total number of ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ speaking characters 39,788 LEADING LADIES RARELY DRIVE THE ACTION IN FILM Of the 100 top films in 2016... And of those Leads and Co Leads*... Female actors were from underrepresented racial / ethnic groups Depicted a 3 Female Lead or (identical to 2015) Co Lead 34 Female actors were at least 45 years of age or older 8 (compared to 5 in 2015) 32 films depicted a female lead or co lead in 2015. *Excludes films w/ensemble casts GENDER & FILM GENRE: FUN AND FAST ARE NOT FEMALE ACTION ANDOR ANIMATION COMEDY ADVENTURE 40.8 36 36 30.7 30.8 23.3 23.4 20 20.9 ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ % OF FEMALE SPEAKING % OF FEMALE SPEAKING % OF FEMALE SPEAKING CHARACTERS CHARACTERS CHARACTERS © DR. STACY L. SMITH GRAPHICS: PATRICIA LAPADULA PAGE THE SEXY STEREOTYPE PLAGUES SOME FEMALES IN FILM Top Films of 2016 13-20 yr old 25.9% 25.6% females are just as likely as 21-39 yr old females to be shown in sexy attire 10.7% 9.2% with some nudity, and 5.7% 3.2% MALES referenced as attractive. FEMALES SEXY ATTIRE SOME NUDITY ATTRACTIVE HOLLYWOOD IS STILL SO WHITE WHITE .% percentage of under- represented characters: 29.2% BLACK .% films have NO Black or African American speaking characters HISPANIC .% 25 OTHER % films have NO Latino speaking characters ASIAN .% 54 films have NO Asian speaking *The percentages of Black, Hispanic, Asian, and Other characters characters have not changed since 2007. -

Abstract Violence and Heteronormativity in Gay

ABSTRACT VIOLENCE AND HETERONORMATIVITY IN GAY-THEMED FILMS Anna-Marie Malley, M.A. Department of Sociology Northern Illinois University, 2017 Kerry O. Ferris, Director Drawing from a sample of 15 “gay/lesbian”-themed films shown in theaters in the U.S. between 1980 to 2016, a qualitative analysis was conducted of the film narratives, looking at the co-constructions of queer (LGBTQ) identity and violence. Films were selected based on widest theatrical release within the genre list “Gay/Lesbian.” Both the categories of queer identity and violence were drawn broadly to incorporate both easily identifiable and “ambiguously” queer characters, as well as to account for both physical and nonphysical forms of violence. Analysis identifies plot developments of exclusion, threat, and physical forms of harm as expressions of violence and argues that to varying degrees these expressions of violence mark queer protagonists and other queer supporting characters as deviant and/or damned within their fictitious social realities. NORTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY DE KALB, ILLINOIS DECEMBER 2017 VIOLENCE AND HETERONORMATIVITY IN GAY-THEMED FILMS BY ANNA-MARIE MALLEY ©2017 Anna-Marie Malley A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY Thesis Director: Kerry O. Ferris ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to my thesis committee: Drs. Ferris, Weffer, and Walther, for their direction and insight through each step of the process. I also want to recognize other faculty, Dr. Rodgers and Dr. Sharp, who have offered advice when needed. I am also deeply grateful to my friends Ana Hernandez, Katarina McGuire, Laura Guilfoyle, Laura Kruczinski, Nabil Juklif, and Rodrigo Martinez for taking the time to read and suggest edits at various stages of the writing process. -

Exploring the Imitation Game Using Machine Intelligence in Improvised Theatre

Proceedings of the Fourteenth Artificial Intelligence and Interactive Digital Entertainment Conference (AIIDE 2018) Improbotics: Exploring the Imitation Game Using Machine Intelligence in Improvised Theatre Kory W. Mathewson,1,2 Piotr Mirowski2 1University of Alberta Edmonton, Alberta, Canada 2HumanMachine, London, UK [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Theatrical improvisation (impro or improv) is a demanding form of live, collaborative performance. Improv is a humor- ous and playful artform built on an open-ended narrative structure which simultaneously celebrates effort and failure. It is thus an ideal test bed for the development and deploy- ment of interactive artificial intelligence (AI)-based conversa- tional agents, or artificial improvisors. This case study intro- duces an improv show experiment featuring human actors and Figure 1: Illustration of two Improbotics rehearsals. artificial improvisors. We have previously developed a deep- learning-based artificial improvisor, trained on movie subti- tles, that can generate plausible, context-based, lines of dia- logue suitable for theatre (Mathewson and Mirowski 2017b). and the audience, short- and long-term memory of narrative In this work, we have employed it to control what a subset elements, and practiced storytelling skills (Johnstone 1979). of human actors say during an improv performance. We also From an audience point of view, improvisors must express give human-generated lines to a different subset of perform- convincing raw emotions and act physically. ers. All lines are provided to actors with headphones and all We agree that improvisational computational storytelling performers are wearing headphones. This paper describes a is a grand challenge in artificial intelligence (AI) as proposed Turing test, or imitation game, taking place in a theatre, with by (Martin and others 2016). -

Ap Euro. Summer Assignment.2019

AP EUROPEAN HISTORY SUMMER ASSIGNMENT 2019-2020 Ms. Lynn Ovaska AP Euro is designed for students who wish to experience the challenge of a college level course that examines the social, political and economic history of Europe during the last 500 years. Since AP classes require substantial commitment and effort, I assume you are ready to put in significant time outside of the classroom to think critically, read curiously, write thoughtfully and study conscientiously about European history. Our summer assignment is the start of important work. If we faithfully adhere to AP Euro curriculum and you complete all course assignments, you will be well-prepared for the AP exam in May to earn college credit. Pick up your textbook from the school bookstore today for your summer assignment! Western Civilization Since 1300: AP Edition (9th Updated Edition) by Jackson J. Spielvogel Summer Assignments: All assignments are due the first day of school. (Time: 10-15 hours) PART 1: Read and Take Notes on Intro and Chapter 11 PART 2: Become an Expert on a Country PART 3: Create and Memorize Maps PART 1: Start the Textbook (3-4 hours) Read and take hand-written notes in the format that works for you. You must have your textbook note taking system set as we beginning the year since we will read over 600 pages and you need to have them summarized. Whether you use Cornell method or classic outlines, loose leaf paper or a notebook, highlighters or a particular pen, you must be able to explain why you use your system. -

Madison Art Cinemas on May 21, 1999

INDIE FOCUS brought to you by The concessions stand has a black veneer with metallic speckles. The accent panels are a mustard color with many abstract color accents. It boasts a beautiful tomato-red espresso machine. The theater offers a few unusual items, not the least of which are Italian coffees and beverages that are imported from Italy, and each espresso, cappuccino, macchiato is ground, packed, and brewed to order. MADISON HISTORY greater Philadelphia (owned and operated by Tony >> The Bonoff Theatre Cimino) got us to the finish line ahead of schedule ART CINEMAS opened in 1912, originally and affordably. Vladimir Shpitalnik (Yale Drama MADISON, CONN. as a single-screen theater, School set, stage, and costume designer) gave the by Arnold Gorlick, Owner with a seating capacity given theater its unique design and color palette; the as 597 in 1941. In 1948 it late Ben Mordecai (former Yale University dean of was remodeled to the plans of architectural firm theater marketing and Broadway producer) worked SCREENS William Riseman Associates and was renamed with me to develop a marketing strategy to launch 2 Madison Theater. the theater; attorney Michael Forte, who negoti- OCCUPANCY: Hoyts Theatres (the Australian chain) purchased ated the lease without knowing how he might be Screen 1: 221 the theater from its local owner-operator. They paid should the deal crater; my film buyer, Rob Screen 2: 202 twinned the theater in 1977. At some point in the Lawinski of Brielle Cinemas, whose tireless passion TOP-PERFORMING TITLES building’s history, it served as a meeting hall and and devotion has helped make the Madison Art 2016 gymnasium as well. -

A.I. Artifical Intelligence About a Boy Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter

A.I. Artifical Intelligence Almost Holy The Art of Racing in the Rain About A Boy Aloha The Artist Abraham Lincoln: Alone in Berlin Vampire Hunter As Time Goes By: The Already Tomorrow in Complete Series Abyss Hong Kong Atomic Blonde Across the Universe Amelie Atonement Ad Astra American Assassin Au Revoir Les Enfants Adam's Rib American Gods: Season 1 The Autobiography of Miss Adaptation The Americans: Seasons 1- Jane Pittman 3 After the Wedding Avatar The American Side The Aftermath Away from Her American Sniper The Age of Adaline Baby Driver Amistad Albert Nobbs Back to the Future II An American in Paris Alien Balzac and the Little Anatomy of a Murder Chinese Seamstress Alien:Covenant And the Band Played On Band of Brothers Alien 3 And Then There Were Bandits Alien Resurrection None The Band's Visit Aliens Angel Has Fallen Bang the Drum Slowly All About Eve Angels in America Barefoot Contessa All Creatures Great and Annie Hall Small Battlestar Galactica: Anywhere But Here Seasons 1-4.5 All My Friends Are Funeral Singers The Apartment Beast All of My Heart: Inn Love Approaching the Unknown Beatriz At Dinner All of My Heart: The Apocalypse Now A Beautiful Day in the Wedding Neighborhood Apollo 13 All the Money in the World Because I Said So Argo All the President's Men Becoming Jane Arn: The Knight Templar Before I Fall Black Hawk Down Bridesmaids Before Midnight Black or White Brigadoon Before Sunrise Black Panther Bridge of Spies Before Sunset Black Swan The Bridge on the River Kwai Being 17 Blade Runner Brightburn Bella Blade Runner -

THE IMITATION GAME – EIN Pädagogisches STRENG GEHEIMES LEBEN Begleitmaterial

Das Film programm zum Wissenschaftsjahr 2019 – KÜNSTLICHE INTELLIGENZ im Rahmen der bundesweiten SchulKinoWochen THE IMITATION GAME – EIN Pädagogisches STRENG GEHEIMES LEBEN Begleitmaterial THE IMITATION GAME Pädagogisches Begleitmaterial 2 WISSENSCHAFT, KINO UND SCHULE Denkende Maschinen, künstliche Menschen – das Kino kennt sie schon eine ganze Weile. Doch die Realität holt mit großen Schritten auf. Ob im Operationssaal, auf der Straße oder bei der Suche Film Der nach einem*r Lebenspartner*in: wir sind umzingelt von Algorithmen und lernenden Systemen. Und täglich kommen neue hinzu. Das Wissenschaftsjahr 2019 widmet sich der Künstlichen Intelligenz mit ihren vielen Facetten und mindestens ebenso vielen spannenden Fragen: Wie lernen Maschinen? Haben sie eigene Rechte? Warum ist die Mensch-Maschine-Kommunikation so kompliziert? Woher kommt das Unbehagen, sich mit menschenähnlichen Robotern zu unterhalten? Einige Filme haben schon vor Jahrzehnten Fragen gestellt, die heute plötzlich akut werden. So etwa der Science Fiction-Klassiker BLADE RUNNER (USA/Hong Kong 1982, ab 11. Klasse), in dem ein Hinweise für Lehrkräfte Hinweise Androidenjäger um einen neuen Blick auf künstliche Menschen ringt. Ähnliche Lernerfahrungen stehen uns allen bevor, wenn der Dokumentarfilm HI, A.I. (Deutschland 2019, ab 9. Klasse) Recht behält. Er taucht ein in die Ausläufer einer neuen Epoche, in der Mensch und Roboter mit großen Schritten aufeinander zu gehen. Das tun sie nach einigen Irrungen und Wirrungen auch im amüsanten und doch tiefsinnigen Animationsfilm WALL•E – DER LETZTE RÄUMT DIE ERDE AUF (USA 2008, ab 3. Klasse). Ernster geht es im Thriller EX MACHINA (Großbritannien 2015, ab 9. Klasse) zu: Zwischen einem jungen Programmierer, seinem Chef und der attraktiven Roboterfrau Ava entspinnt sich ein raffinierter Machtkampf. -

Weinstein Company and Amc Theatres Offer High School Students Opportunity to See the Imitation Game Free on March 6

WEINSTEIN COMPANY AND AMC THEATRES® OFFER HIGH SCHOOL STUDENTS OPPORTUNITY TO SEE THE IMITATION GAME FREE ON MARCH 6TH OSCAR® WINNING SCREENWRITER GRAHAM MOORE TO INTRODUCE FILM March 2, 2015 (New York, NY) – The Weinstein Company (TWC) and AMC Theatres announced today they are partnering to provide high school students nationwide with free tickets to Academy Award® winning film THE IMITATION GAME at AMC on Friday, March 6 only. The companies are offering complimentary tickets to the movie to 50,000 students, with AMC leading outreach to schools and community groups, with a special focus on high school computer classes, math and science teams and LGBT clubs being encouraged to attend at 180 theaters presenting the movie. The free high school screenings of the film at AMC will include a special taped introductory message from IMITATION GAME screenwriter Graham Moore, who was awarded last weekend with the Oscar® for Best Adapted Screenplay. Students can present their student ID at the participating AMC box office to receive a free ticket. For information on theatre locations and showtimes on Friday, March 6th, please visit: http://www.amctheatres.com/ Commented TWC Co-Chairman Harvey Weinstein: “As Graham Moore said in his brilliant speech at the Oscars, Turing’s legacy should inspire kids to be individuals, stay weird and stay different. We’re so pleased to be joining with the remarkable team at AMC in giving students all over the country an opportunity to see THE IMITATION GAME. Alan Turing’s story is an incredibly important part of history