Abstract Violence and Heteronormativity in Gay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reflections from the Developments of School Science Curricula

Imitation game: Reflections from the developments of school science curricula SONG, Jinwoong (宋眞雄) Department of Physics Education, Seoul National University What will fulfill this need can be stated in equally simple terms. It is, ironically enough, that science be taught as science. (Joseph J. Schwab, 1962: 188-9) 1.Introduction The Imitation Game is a 2014 British historical drama film directed by Morten Tyldu m and written by Graham Moore, based on the biography Alan Turing: The Enigma by A ndrew Hodges. It stars Benedict Cumberbatch as British cryptanalyst Alan Turing, who dec rypted German intelligence codes for the British government during the Second World War (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Imitation_Game). The ’Imitation Game’ refers to so-calle d ‘Turing Test’ which is a test for artificial intelligence suggested by a famous British ma thematician, Alan Turing (1912-54), who is known as the father of the computer. Through his paper, “Computing machinery and intelligence” (1950), Tuning gave a conceptual fou ndation of AI (Artificial Intelligence), by suggesting the Turing Test, “a test of a machine’ s ability to exhibit intelligent behavior equivalent to, or indistinguishable from, that of a h uman.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turing_test) Science is now considered as one of the core (often three of them) subjects across th e world, together with the national language and mathematics. For example, in PISA studi es, science is included in the three main areas, with literacy and mathematics (e.g. OECD, 2018). And, in TIMSS studies, science and mathematics are the two main subjects for th e international comparison (https://timssandpirls.bc.edu/timss2015/). -

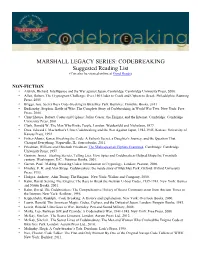

CODEBREAKING Suggested Reading List (Can Also Be Viewed Online at Good Reads)

MARSHALL LEGACY SERIES: CODEBREAKING Suggested Reading List (Can also be viewed online at Good Reads) NON-FICTION • Aldrich, Richard. Intelligence and the War against Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. • Allen, Robert. The Cryptogram Challenge: Over 150 Codes to Crack and Ciphers to Break. Philadelphia: Running Press, 2005 • Briggs, Asa. Secret Days Code-breaking in Bletchley Park. Barnsley: Frontline Books, 2011 • Budiansky, Stephen. Battle of Wits: The Complete Story of Codebreaking in World War Two. New York: Free Press, 2000. • Churchhouse, Robert. Codes and Ciphers: Julius Caesar, the Enigma, and the Internet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. • Clark, Ronald W. The Man Who Broke Purple. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1977. • Drea, Edward J. MacArthur's Ultra: Codebreaking and the War Against Japan, 1942-1945. Kansas: University of Kansas Press, 1992. • Fisher-Alaniz, Karen. Breaking the Code: A Father's Secret, a Daughter's Journey, and the Question That Changed Everything. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, 2011. • Friedman, William and Elizebeth Friedman. The Shakespearian Ciphers Examined. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1957. • Gannon, James. Stealing Secrets, Telling Lies: How Spies and Codebreakers Helped Shape the Twentieth century. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2001. • Garrett, Paul. Making, Breaking Codes: Introduction to Cryptology. London: Pearson, 2000. • Hinsley, F. H. and Alan Stripp. Codebreakers: the inside story of Bletchley Park. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993. • Hodges, Andrew. Alan Turing: The Enigma. New York: Walker and Company, 2000. • Kahn, David. Seizing The Enigma: The Race to Break the German U-boat Codes, 1939-1943. New York: Barnes and Noble Books, 2001. • Kahn, David. The Codebreakers: The Comprehensive History of Secret Communication from Ancient Times to the Internet. -

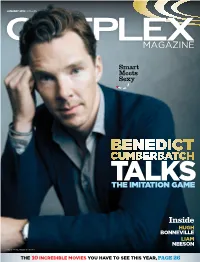

Benedict Cumberbatch Talks the Imitation Game

JANUARY 2015 | VOLUME 16 | NUMBER 1 Smart Meets Sexy BENEDICT CUMBERBATCH TALKS THE IMITATION GAME Inside HUGH BONNEVILLE LIAM NEESON PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 41619533 THE 10 INCREDIBLE MOVIES YOU HAVE TO SEE THIS YEAR, PAGE 26 CONTENTS JANUARY 2015 | VOL 16 | Nº1 COVER STORY 40 GENIUS ROLE Benedict Cumberbatch’s fervent fans won’t be disappointed with his latest role. The Imitation Game casts the 38-year-old Brit as Alan Turing, a gay, mathematical genius who helped hasten the end of WWII. Here he talks about bringing Turing to life and his various other talents BY INGRID RANDOJA REGULARS 4 EDITOR’S NOTE 8 SNAPS 10 IN BRIEF 14 SPOTLIGHT: CANADA 16 ALL DRESSED UP 20 IN THEATRES 44 CASTING CALL 47 RETURN ENGAGEMENT 48 AT HOME 50 FINALLY… FEATURES IMAGE HARGRAVE/AUGUST AUSTIN BY PHOTO COVER 26 2015’S BIG PICS! 32 FABLED CAST 34 MAN OF ACTION 38 PAPA BEAR It’s going to be an epic year We break down which famous Taken 3 star Liam Neeson Paddington’s Hugh Bonneville at the movies. We take you actors play which well-known talks about his longtime says playing father figure to a through the 10 films you must fairy tale characters in love of action movies, and mischievous talking bear gave see, starting with the return of the musical extravaganza recent decision to get clean him the chance to revisit his Star Wars! Into the Woods and healthy own childhood BY INGRID RANDOJA BY INGRID RANDOJA BY BOB STRAUSS BY INGRID RANDOJA JANUARY 2015 | CINEPLEX MAGAZINE | 3 EDITOR’S NOTE PUBLISHER SALAH BACHIR EDITOR MARNI WEISZ DEPUTY EDITOR INGRID RANDOJA ART DIRECTOR TREVOR THOMAS STEWART ASSISTANT ART DIRECTOR STEVIE SHIPMAN VICE PRESIDENT, PRODUCTION SHEILA GREGORY CONTRIBUTORS LEO ALEFOUNDER, BOB STRAUSS ADVERTISING SALES FOR CINEPLEX MAGAZINE AND LE MAGAZINE CINEPLEX IS HANDLED BY CINEPLEX MEDIA. -

Savages Randilee Sequeira Larson Concordia University - Portland

Concordia University - Portland CU Commons Undergraduate Theses Spring 2017 Savages Randilee Sequeira Larson Concordia University - Portland Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.cu-portland.edu/theses Part of the Creative Writing Commons Recommended Citation Sequeira Larson, Randilee, "Savages" (2017). Undergraduate Theses. 149. http://commons.cu-portland.edu/theses/149 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by CU Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of CU Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2 Savages A senior thesis submitted to The Department of English College of Arts & Sciences In partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Bachelor of Arts degree in English by Randilee Sequeira Larson Faculty Supervisor _________________________________________ __________________ Dr. Ceiridwen Terrill Date Department Chair _________________________________________ __________________ Dr. Kim Knutsen Date Dean, College of Arts & Sciences ___________________________________________ __________________ Rev. Dr. David Kluth Date Chief Academic Officer _____________________________________ __________________ Dr. Joe Mannion Date Concordia University Portland, Oregon May, 2017 3 Abstract Savages is a memoir chronicling my near-immediate expulsion from the Army upon arriving to Basic Training. The story begins with my discharge, made on the grounds that I was “psychologically unstable” and therefore couldn’t be trusted as a soldier. The diagnosis was based primarily on a sexual assault I went through several months before shipping. When I was given my in-processing packet on the first day, one of the questions asked “Have you ever been raped or sexually assaulted?” By opting for honesty and marking yes, I sealed my fate and lost my job in a single pen stoke. -

Contenido Estrenos Mexicanos

Contenido estrenos mexicanos ............................................................................120 programas especiales mexicanos .................................. 122 Foro de los Pueblos Indígenas 2019 .......................................... 122 Programa Exilio Español ....................................................................... 123 introducción ...........................................................................................................4 Programa Luis Buñuel ............................................................................. 128 Presentación ............................................................................................................... 5 El Día Después ................................................................................................ 132 ¡Bienvenidos a Morelia! ................................................................................... 7 Feratum Film Festival .............................................................................. 134 Mensaje de la Secretaría de Cultura ....................................................8 ......... 10 Mensaje del Instituto Mexicano de Cinematografía funciones especiales mexicanas .......................................137 17° Festival Internacional de Cine de Morelia ............................11 programas especiales internacionales................148 ...........................................................................................................................12 jurados Programa Agnès Varda ...........................................................................148 -

Why Python for Chatbots

Schedule: 1. History of chatbots and Artificial Intelligence 2. The growing role of Chatbots in 2020 3. A hands on look at the A.I Chatbot learning sequence 4. Q & A Session Schedule: 1. History of chatbots and Artificial Intelligence 2. The growing role of Chatbots in 2020 3. A hands on look at the A.I Chatbot learning sequence 4. Q & A Session Image credit: Archivio GBB/Contrasto/Redux History •1940 – The Bombe •1948 – Turing Machine •1950 – Touring Test •1980 Zork •1990 – Loebner Prize Conversational Bots •Today – Siri, Alexa Google Assistant Image credit: Photo 172987631 © Pop Nukoonrat - Dreamstime.com 1940 Modern computer history begins with Language Analysis: “The Bombe” Breaking the code of the German Enigma Machine ENIGMA MACHINE THE BOMBE Enigma Machine image: Photographer: Timothy A. Clary/AFP The Bombe image: from movie set for The Imitation Game, The Weinstein Company 1948 – Alan Turing comes up with the concept of Turing Machine Image CC-BY-SA: Wikipedia, wvbailey 1948 – Alan Turing comes up with the concept of Turing Machine youtube.com/watch?v=dNRDvLACg5Q 1950 Imitation Game Image credit: Archivio GBB/Contrasto/Redux Zork 1980 Zork 1980 Text parsing Loebner Prize: Turing Test Competition bit.ly/loebnerP Conversational Chatbots you can try with your students bit.ly/MITsuku bit.ly/CLVbot What modern chatbots do •Convert speech to text •Categorise user input into categories they know •Analyse the emotion emotion in user input •Select from a range of available responses •Synthesize human language responses Image sources: Biglytics -

From Real Time to Reel Time: the Films of John Schlesinger

From Real Time to Reel Time: The Films of John Schlesinger A study of the change from objective realism to subjective reality in British cinema in the 1960s By Desmond Michael Fleming Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2011 School of Culture and Communication Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne Produced on Archival Quality Paper Declaration This is to certify that: (i) the thesis comprises only my original work towards the PhD, (ii) due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all other material used, (iii) the thesis is fewer than 100,000 words in length, exclusive of tables, maps, bibliographies and appendices. Abstract The 1960s was a period of change for the British cinema, as it was for so much else. The six feature films directed by John Schlesinger in that decade stand as an exemplar of what those changes were. They also demonstrate a fundamental change in the narrative form used by mainstream cinema. Through a close analysis of these films, A Kind of Loving, Billy Liar, Darling, Far From the Madding Crowd, Midnight Cowboy and Sunday Bloody Sunday, this thesis examines the changes as they took hold in mainstream cinema. In effect, the thesis establishes that the principal mode of narrative moved from one based on objective realism in the tradition of the documentary movement to one which took a subjective mode of narrative wherein the image on the screen, and the sounds attached, were not necessarily a record of the external world. The world of memory, the subjective world of the mind, became an integral part of the narrative. -

Winter/Spring 2020 Calendar

WINTER/SPRING 2020 DIRECTORS MESSAGE As the calendar turns over from 2019 to 2020, never This season we also highlight UCLA’s Centennial has the Hammer’s imperative “to build a more just with a special exhibition that is the result of a world” felt more urgent. In the aftermath of the collaboration across disciplines at the university. impeachment hearings, the presidential election Inside the Mask highlights extraordinary objects lies ahead and the global climate crisis is upon us. from the collection of the Fowler Museum and is Holding firm to facts, actively participating in the co-organized by acclaimed theater director and democratic process, and taking action are critical UCLA professor Peter Sellars, and Hammer curator for all of us in 2020. I am proud of the programs and Allegra Pesenti. exhibitions here at the Hammer that bring clarity, As we head into the new year, I am pleased to perspective, and purpose to our understanding of welcome Larry Jackson, global creative director the many issues we all face. of Apple Music, to our Board of Directors; as well To that end, I am honored to say that the Hammer as two new members of our Board of Overseers, art will be a voting center in the Democratic primaries. collector and philanthropist Carla Emil and cohead Larry Jackson As you may have read, the process for voting in of the Motion Picture Group at Creative Artists California has changed: regardless of where you live Agency and collector Joel Lubin. Larry, Carla, and in Los Angeles, you can vote at any voting center— Joel will join our other board members to guide the polls will be open over multiple days. -

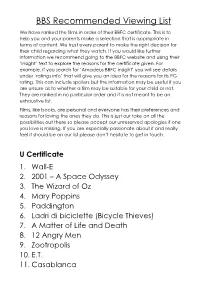

BBS Recommended Viewing List

BBS Recommended Viewing List We have ranked the films in order of their BBFC certificate. This is to help you and your parents make a selection that is appropriate in terms of content. We trust every parent to make the right decision for their child regarding what they watch. If you would like further information we recommend going to the BBFC website and using their ‘Insight’ text to explore the reasons for the certificate given. For example, if you search for ‘Amadeus BBFC insight’ you will see details under ‘ratings info’ that will give you an idea for the reasons for its PG rating. This can include spoilers but the information may be useful if you are unsure as to whether a film may be suitable for your child or not. They are ranked in no particular order and it is not meant to be an exhaustive list. Films, like books, are personal and everyone has their preferences and reasons for loving the ones they do. This is just our take on all the possibilities out there so please accept our unreserved apologies if one you love is missing. If you are especially passionate about it and really feel it should be on our list please don’t hesitate to get in touch. U Certificate 1. Wall-E 2. 2001 – A Space Odyssey 3. The Wizard of Oz 4. Mary Poppins 5. Paddington 6. Ladri di biciclette (Bicycle Thieves) 7. A Matter of Life and Death 8. 12 Angry Men 9. Zootropolis 10. E.T. 11. Casablanca 12. Sense and Sensibility 13. -

Inequality in 900 Popular Films: Gender, Race/Ethnicity, LGBT, & Disability from 2007‐2016

July 2017 INEQUALITY IN POPULAR FILMS MEDIA, DIVERSITY, & SOCIAL CHANGE INITIATIVE USC ANNENBERG MDSCInitiative Facebook.com/MDSCInitiative THE NEEDLE IS NOT MOVING ON SCREEN FOR FEMALES IN FILM Prevalence of female speaking characters across 900 films, in percentages Percentage of 900 films with 32.8 32.8 Balanced Casts 12% 29.9 30.3 31.4 31.4 28.4 29.2 28.1 Ratio of males to females 2.3 : 1 Total number of ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ speaking characters 39,788 LEADING LADIES RARELY DRIVE THE ACTION IN FILM Of the 100 top films in 2016... And of those Leads and Co Leads*... Female actors were from underrepresented racial / ethnic groups Depicted a 3 Female Lead or (identical to 2015) Co Lead 34 Female actors were at least 45 years of age or older 8 (compared to 5 in 2015) 32 films depicted a female lead or co lead in 2015. *Excludes films w/ensemble casts GENDER & FILM GENRE: FUN AND FAST ARE NOT FEMALE ACTION ANDOR ANIMATION COMEDY ADVENTURE 40.8 36 36 30.7 30.8 23.3 23.4 20 20.9 ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ % OF FEMALE SPEAKING % OF FEMALE SPEAKING % OF FEMALE SPEAKING CHARACTERS CHARACTERS CHARACTERS © DR. STACY L. SMITH GRAPHICS: PATRICIA LAPADULA PAGE THE SEXY STEREOTYPE PLAGUES SOME FEMALES IN FILM Top Films of 2016 13-20 yr old 25.9% 25.6% females are just as likely as 21-39 yr old females to be shown in sexy attire 10.7% 9.2% with some nudity, and 5.7% 3.2% MALES referenced as attractive. FEMALES SEXY ATTIRE SOME NUDITY ATTRACTIVE HOLLYWOOD IS STILL SO WHITE WHITE .% percentage of under- represented characters: 29.2% BLACK .% films have NO Black or African American speaking characters HISPANIC .% 25 OTHER % films have NO Latino speaking characters ASIAN .% 54 films have NO Asian speaking *The percentages of Black, Hispanic, Asian, and Other characters characters have not changed since 2007. -

Rupert Everett ~ 36 Screen Credits

Rupert Everett ~ 36 Screen Credits Look at that lip. Hauteur, condescension, disdain writ large. "I am a very limited actor. There's a certain amount I can do and that's it," said Everett in 2014. Maybe so, but - see My Best Friend's Wedding, An Ideal Husband, Separate Lies or Unconditional Love - how well he does it. Born in Burnham Deepdale, Norfolk on 29 May 1959 the second son of parents Anthony and Sara, RUPERT JAMES HECTOR EVERETT is of English, Scottish, Irish and more distant German and Dutch ancestry. His father, who died in 2009, was a Major in the British Army who later worked in business. When he was six, Rupert was taken into Braintree for his first trip to a cinema. There was a long queue, the child was typically fretful and the grown-ups thought about leaving, but finally decided not to: And so my mother bought the fateful tickets and unknowingly guided me through a pair of swing doors into the rest of my life ... ... Those huge curtains silently swished open and Mary Poppins sprang across the footlights and into my heart. After preliminary instruction from a governess, Everett was educated at Far- leigh House School, Andover from seven to thirteen then at Ampleforth College, Yorkshire from thirteen to sixteen, at which point he absconded to London to become an actor. After two years of living the bohemian life to the full (if not excess), he won a coveted place at the Central School of Speech and Drama, but after attending for two tempestuous and more or less unrewarding years was told not to return for a third. -

Casey Affleck Anna Pniowsky

CONDOR DISTRIBUTION présente une production Black Bear Pictures / Sea Change Media CASEY AFFLECK ANNA PNIOWSKY un film écrit & réalisé par CASEY AFFLECK avec la participation de ELISABETH MOSS 2019 – Couleur – 119 mn - États-Unis Matériel presse en HD sur https://www.condor-films.fr/film/light-of-my-life/ SORTIE LE 12 AOÛT 2020 DISTRIBUTION RELATIONS PRESSE Condor Distribution Bossa-Nova / Michel Burstein 11, rue de Rome – 75008 Paris 32, bd Saint-Germain - 75005 Paris Tél : 01 55 94 91 70 Tél : 01 43 26 26 26 [email protected] [email protected] www.condor-films.fr www.bossa-nova.info 1 SYNOPSIS Dans un futur proche où la population féminine a été éradiquée, un père tâche de protéger Rag, sa fille unique, miraculeusement épargnée. Dans ce monde brutal dominé par les instincts primaires, la survie passe par une stricte discipline, faite de fuite permanente et de subterfuges. Mais il le sait, son plus grand défi est ailleurs: alors que tout s'effondre, comment maintenir l'illusion d'un quotidien insouciant et préserver la complicité fusionnelle avec sa fille ? 2 NOTE D’INTENTION DU RÉALISATEUR En tant que cinéaste, je suis attiré par les histoires qui mettent en valeur notre humanité. L'histoire d'un parent dévoué par-dessus tout à son enfant en est une dans laquelle j'espère que tout un chacun pourra se retrouver. En tant que père de deux enfants, je leur ai raconté beaucoup d'histoires au moment du coucher. Chacune, bien que parfois inspirée de celle d'avant, devait être inventée de toutes pièces sous peine d’encourir la critique de leur part.