Annual Safety Performance Report 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Operator's Story Appendix

Railway and Transport Strategy Centre The Operator’s Story Appendix: London’s Story © World Bank / Imperial College London Property of the World Bank and the RTSC at Imperial College London Community of Metros CoMET The Operator’s Story: Notes from London Case Study Interviews February 2017 Purpose The purpose of this document is to provide a permanent record for the researchers of what was said by people interviewed for ‘The Operator’s Story’ in London. These notes are based upon 14 meetings between 6th-9th October 2015, plus one further meeting in January 2016. This document will ultimately form an appendix to the final report for ‘The Operator’s Story’ piece Although the findings have been arranged and structured by Imperial College London, they remain a collation of thoughts and statements from interviewees, and continue to be the opinions of those interviewed, rather than of Imperial College London. Prefacing the notes is a summary of Imperial College’s key findings based on comments made, which will be drawn out further in the final report for ‘The Operator’s Story’. Method This content is a collation in note form of views expressed in the interviews that were conducted for this study. Comments are not attributed to specific individuals, as agreed with the interviewees and TfL. However, in some cases it is noted that a comment was made by an individual external not employed by TfL (‘external commentator’), where it is appropriate to draw a distinction between views expressed by TfL themselves and those expressed about their organisation. -

Tunnel from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia This Article Is About Underground Passages

Tunnel From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This article is about underground passages. For other uses, see Tunnel (disambiguation). "Underpass" redirects here. For the John Foxx song, see Underpass (song). Entrance to a road tunnel inGuanajuato, Mexico. Utility tunnel for heating pipes between Rigshospitalet and Amagerværket in Copenhagen,Denmark Tunnel on the Taipei Metro inTaiwan Southern portal of the 421 m long (1,381 ft) Chirk canal tunnel A tunnel is an underground or underwater passageway, dug through the surrounding soil/earth/rock and enclosed except for entrance and exit, commonly at each end. A pipeline is not a tunnel, though some recent tunnels have used immersed tube construction techniques rather than traditional tunnel boring methods. A tunnel may be for foot or vehicular road traffic, for rail traffic, or for a canal. The central portions of a rapid transit network are usually in tunnel. Some tunnels are aqueducts to supply water for consumption or for hydroelectric stations or are sewers. Utility tunnels are used for routing steam, chilled water, electrical power or telecommunication cables, as well as connecting buildings for convenient passage of people and equipment. Secret tunnels are built for military purposes, or by civilians for smuggling of weapons, contraband, or people. Special tunnels, such aswildlife crossings, are built to allow wildlife to cross human-made barriers safely. Contents [hide] 1 Terminology 2 History o 2.1 Clay-kicking 3 Geotechnical investigation and design o 3.1 Choice of tunnels vs. -

Rail Accident Report

Rail Accident Report Fatal collision between a Super Voyager train and a car on the line at Copmanthorpe 25 September 2006 Report 33/2007 September 2007 This investigation was carried out in accordance with: l the Railway Safety Directive 2004/49/EC; l the Railways and Transport Safety Act 2003; and l the Railways (Accident Investigation and Reporting) Regulations 2005. © Crown copyright 2007 You may re-use this document/publication (not including departmental or agency logos) free of charge in any format or medium. You must re-use it accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and you must give the title of the source publication. Where we have identified any third party copyright material you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This document/publication is also available at www.raib.gov.uk. Any enquiries about this publication should be sent to: RAIB Email: [email protected] The Wharf Telephone: 01332 253300 Stores Road Fax: 01332 253301 Derby UK Website: www.raib.gov.uk DE21 4BA This report is published by the Rail Accident Investigation Branch, Department for Transport. Fatal collision between a Super Voyager train and a car at Copmanthorpe, 25 September 2006 Contents Introduction 5 Summary of the report 6 Key facts about the accident 6 Immediate cause, contributory factors, underlying causes 7 Severity of consequences 7 Recommendations 7 The Accident 8 Summary of the accident 8 The parties involved 8 Location 9 External circumstances 9 Train -

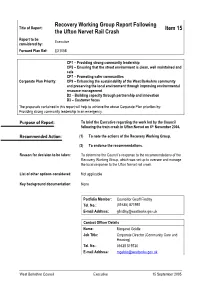

Recovery Working Group Report Following the Ufton Nervet Rail

Recovery Working Group Report Following Title of Report: Item 15 the Ufton Nervet Rail Crash Report to be Executive considered by: Forward Plan Ref: EX1058 CP1 – Providing strong community leadership CP5 – Ensuring that the street environment is clean, well maintained and safe CP7 – Promoting safer communities Corporate Plan Priority: CP9 – Enhancing the sustainability of the West Berkshire community and preserving the local environment through improving environmental resource management D2 – Building capacity through partnership and innovation D3 – Customer focus The proposals contained in this report will help to achieve the above Corporate Plan priorities by: Providing strong community leadership in an emergency. Purpose of Report: To brief the Executive regarding the work led by the Council following the train crash in Ufton Nervet on 6 th November 2004. Recommended Action: (1) To note the actions of the Recovery Working Group. (2) To endorse the recommendations. Reason for decision to be taken: To determine the Council’s response to the recommendations of the Recovery Working Group, which was set up to oversee and manage the local response to the Ufton Nervet rail crash. List of other options considered: Not applicable Key background documentation: None Portfolio Member: Councillor Geoff Findlay Tel. No.: (01635) 871992 E-mail Address: [email protected] Contact Officer Details Name: Margaret Goldie Job Title: Corporate Director (Community Care and Housing) Tel. No.: 01635 519730 E-mail Address: [email protected] West Berkshire Council Executive 15 September 2005 Implications Policy: The recommendations contained within the report include some proposed changes to the Council’s Emergency Planning procedures. Personnel: Some recommendations will require further training for staff. -

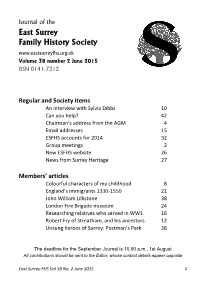

Journal JUN15

Journal of the East Surrey Family History Society www.eastsurreyfhs.org.uk Volume 38 number 2 June 2015 ISSN 0141-7312 Regular and Society items An interview with Sylvia Dibbs 10 Can you help? 42 Chairman’s address from the AGM 4 Email addresses 15 ESFHS accounts for 2014 32 Group meetings 2 New ESFHS website 26 News from Surrey Heritage 27 Members’ articles Colourful characters of my childhood 8 England’s immigrants 1330-1550 21 John William Lillistone 38 London Fire Brigade museum 24 Researching relatives who served in WW1 16 Robert Fry of Streatham, and his ancestors 12 Unsung heroes of Surrey: Postman’s Park 36 The deadline for the September Journal is 10.00 a.m., 1st August All contributions should be sent to the Editor, whose contact details appear opposite East Surrey FHS Vol 38 No. 2 June 2015 1 Group meetings June 4 Surrey Gardens in Walworth 1831 – 1878 Stephen Humphrey Sutton Stephen is a Local and Family Historian in Southwark 8 Had you thought of looking at . ? Hilary Blanford Southwark A look at some unusual sources, and ideas to add some flesh to the bones of your ancestors 16 What did your ancestors leave behind? Croydon This is an open meeting: please bring anything relevant to your family history and share your memorabilia 24 Hearth Tax and other 17th century sources Francis Howcutt Lingfield July 2 My ancestors were Thames watermen Pat Hilbert Sutton Pat has been a family historian for over 20 years and is currently Chairman of the East Dorset group of the Somerset and Dorset FHS. -

Chapter Four – a Good Public Transport Experience

A GOOD PUBLIC TRANSPORT EXPERIENCE 129 Chapter four – A good public transport experience London has one of the most extensive public transport networks in the world, with more than 9 million trips made every day by bus, tram, Tube, train and river boat. Use of the public transport system has increased by 65 per cent since 2000, largely because of enhanced services and an improved customer experience. An easy to use and accessible public transport system is an essential part of the Healthy Streets Approach as it gives people alternatives to car use for journeys that are not possible on foot or by cycle. By providing the most efficient and affordable option for journeys that are either impractical or too long to walk or cycle, public transport has helped to reduce Londoners’ dependency on cars during the past 15 years and this trend must continue. VERSION FOR PUBLICATION A GOOD PUBLIC TRANSPORT EXPERIENCE 131 401 As it grows, the city requires the public This chapter sets out the importance of The whole journey ‘By 2041, the transport capacity to reduce crowding a whole journey approach, where public A good public transport experience and support increasing numbers of transport improvements are an integral means catering for the whole journey, public transport people travelling more actively, efficiently part of delivering the Healthy Streets with all its stages, from its planning to and sustainably. Figure 18 shows that Approach. The chapter then explains the return home. All public transport system will need by 2041 the public transport system will in four sections how London’s public journeys start or finish on foot or by need to cater for up to around 15 million transport services can be improved for cycle, and half of all walking in London is trips every day. -

11 July 2006 Mumbai Train Bombings

11 July 2006 Mumbai train bombings July 2006 Mumbai train bombings One of the bomb-damaged coaches Location Mumbai, India Target(s) Mumbai Suburban Railway Date 11 July 2006 18:24 – 18:35 (UTC+5.5) Attack Type Bombings Fatalities 209 Injuries 714 Perpetrator(s) Terrorist outfits—Student Islamic Movement of India (SIMI), Lashkar-e-Toiba (LeT; These are alleged perperators as legal proceedings have not yet taken place.) Map showing the 'Western line' and blast locations. The 11 July 2006 Mumbai train bombings were a series of seven bomb blasts that took place over a period of 11 minutes on the Suburban Railway in Mumbai (formerly known as Bombay), capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra and India's financial capital. 209 people lost their lives and over 700 were injured in the attacks. Details The bombs were placed on trains plying on the western line of the suburban ("local") train network, which forms the backbone of the city's transport network. The first blast reportedly took place at 18:24 IST (12:54 UTC), and the explosions continued for approximately eleven minutes, until 18:35, during the after-work rush hour. All the bombs had been placed in the first-class "general" compartments (some compartments are reserved for women, called "ladies" compartments) of several trains running from Churchgate, the city-centre end of the western railway line, to the western suburbs of the city. They exploded at or in the near vicinity of the suburban railway stations of Matunga Road, Mahim, Bandra, Khar Road, Jogeshwari, Bhayandar and Borivali. -

Betonösszetevők Hatása Az Alagútfalazatok Hőtűrésére

Budapesti Műszaki és Gazdaságtudományi Egyetem Építőanyagok és Mérnökgeológia Tanszék 1111 Budapest, Műegyetem rkp. 3. PhD értekezés BETONÖSSZETEVŐK HATÁSA AZ ALAGÚTFALAZATOK HŐTŰRÉSÉRE Fehérvári Sándor okl. építőmérnök Tudományos vezető: Dr. Salem Georges Nehme, PhD egyetemi docens Budapest 2009. április PhD értekezés Betonösszetevők hatása az alagútfalazatok hőtűrésére Fehérvári Sándor Tartalom Jelölések és rövidítések d Fogalmak d ELŐSZÓ I 1. BEVEZETÉS, PROBLÉMAFELVETÉS 1 1.1 Alagúti katasztrófák, balesetek 1 1.2 Hazai előírások, tapasztalatok 2 1.3 Az értekezés témája 3 1.4 Az értekezés célkitűzései 3 2. AZ ALAGÚTTÜZEK TERMÉSZETE 4 2.1 A hőteher 4 3. AZ ALAGÚTTÜZEK HATÁSA A VASBETON FALAZATRA 7 3.1 Tűzvédelem 7 3.2 Vasbeton alagútfalazatok viselkedése tűz esetén 7 3.3 A vasbeton falazat tűzállósága 7 3.4 A beton viselkedése nagy hőmérsékleten 8 3.5 Mechanikai jellemzők változása 9 3.6 Réteges leválás 13 4. LABORATÓRIUMI KÍSÉRLETEK 14 4.1 Kísérletek áttekintése 14 4.2 Kísérleti receptúrák 14 4.2.1 Cementpépek 14 4.2.2 Betonok 16 4.3 Hőterheléses vizsgálat 17 4.3.1 Általános vizsgálat 17 4.3.2 Alkalmazott hőfoklépcsők és próbatest darabszámok 17 4.3.3 Különleges hűtési módok 18 4.4 Vizsgálatokhoz felhasznált eszközök 19 4.5 Eredmények ábrázolása 19 5. A TISZTA PORTLANDCEMENT FAJLAGOS FELÜLETE ÉS A CEMENTPÉP VÍZ/CEMENT TÉNYEZŐJÉNEK HATÁSA A CEMENTKŐ MARADÓ NYOMÓSZILÁRDSÁGÁRA ÉS KÉMIAI JELLEMZŐIRE 20 5.1 Fajlagos felület hatása a tiszta portlandcementek hőtűrésére 20 5.2 Víz/cement tényező hatása a tiszta portlandcementek hőtűrésére 22 5.3 Ca(OH)2 szint változása a hőmérséklet emelkedésével 24 5.4 Összefoglalás 25 6. KIEGÉSZÍTŐ-ANYAGOK HATÁSA A CEMENTKŐ MARADÓ MECHANIKAI JELLEMZŐIRE 26 6.1 Mészkőliszt és kohósalak adagolásának hatása a cementkő maradó nyomószilárdsági jellemzőire, állandó víz/finomrész tényező esetén 27 6.2 Mészkőliszt, dolomitliszt, kohósalak, kvarcliszt és barit adagolásának hatása azonos víz/portlandcement tényező esetén a cementkő hőterhelés utáni maradó nyomószilárdsági jellemzőire 29 6.3 Összefoglalás 32 7. -

2005 Annual Return

Annual Return Reporting on the year 2004/05 31 July 2005 Page 2 Contents Executive summary.....................................................................................................................................................................................................5 Introduction..................................................................................................................................................................................................................16 Network Rail’s regulatory targets....................................................................................................................................................................20 Key performance indicators................................................................................................................................................................................24 Section 1 – Operational performance .........................................................................................................................................................27 Introduction...................................................................................................................................................................................................27 Summarised network-wide data (delays to major operators) ........................................................................................28 National delay data by cause...............................................................................................................................................................30 -

Annual Safety Performance Report 2010/11

Annual Safety Performance Report 2010/11 If you would like to give feedback on any of the material contained in this report, or if you have any suggestions for future editions, please contact: Liz Davies Safety Intelligence Strategy Manager RSSB Block 2, Angel Square 1 Torrens Street London EC1V 1NY 020 3142 5475 [email protected] The report may be downloaded from the RSSB website: www.rssb.co.uk. Additional hard copies may be ordered at cost price by contacting the RSSB enquiry desk on 020 3142 5400. Rail Safety and Standards Board 2011 Contents __________________________________________________________________________ Contents Executive summary v 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Purpose of the report 1 1.2 Scope of the report 1 1.3 How the report analyses safety 1 1.3.1 Person type 1 1.3.2 Fatalities, injuries and FWI 2 1.3.3 Methodology 3 1.4 Data quality 3 1.5 RSSB reporting to be used for ORR’s National Rail Trends 4 1.6 Report structure 4 2 Safety overview 5 2.1 System risk profile 6 2.1.1 Fatalities 6 2.1.2 Fatalities and weighted injuries 7 2.2 Fatalities and injuries in 2010/11 8 2.3 Notable safety-related occurrences of 2010/11 9 2.4 Long-term historical trends 13 2.4.1 Rail usage 13 2.4.2 Fatalities 14 2.4.3 Train accidents 15 2.5 Looking to the future 16 2.5.1 Future influences on safety 16 2.5.2 Research and Development Programme 19 2.5.3 Sustainable Rail Programme 19 2.6 Safety overview key safety facts 20 3 Progress against industry trajectories and targets 21 3.1 Trajectories of the 2009 – 2014 SSP 22 3.1.1 How progress towards -

Safety Case for the Introduction of New Technology Into an Existing Railway System

Safety Case for the Introduction of New Technology into an Existing Railway System Peri Smith M.Sc., B.Eng.,DIC 20th September 2016 Imperial College London Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering Centre for Transport Studies Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy and the Diploma of Imperial College London Declaration I hereby declare that the work here within is that of the author and work of others has been appropriately referenced. Some of the material represented in this thesis has been published in conference and journal material as referenced in this thesis. PhD Student: Miss Peri Smith Date: September 2016 Academic Supervisor: Professor Washington Ochieng Date: September 2016 Academic Supervisor: Dr Arnab Majumdar Date: September 2016 ‘The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives licence. Researchers are free to copy, distribute or transmit the thesis on the condition that they attribute it, that they do not use it for commercial purposes and that they do not alter, transform or build upon it. For any reuse or redistribution, researchers must make clear to others the licence terms of this work’. 3 Dedication I dedicate this research to my great-grandmother Metella Smith. 4 Abstract This thesis addresses safety in the railway industry with a focus on safety culture, defined by the United Kingdom’s Health and Safety Executive as ‘the behavioural aspects (i.e. what people do) and the situational aspects of the company (i.e. what the organisation has)’. Current safety management systems do not appropriately incorporate safety culture. -

The Southall Rail Accident Inquiry Report Professor John Uff QC Freng

iealth 6 Safety Commission The Southall Rail Accident Inquiry Report - Professor John Uff QC FREng 2 Erratum The Southali Rail Accident Inquiry Report iSBN 0 7176 1757 2 Annex 09 Passengers & Staff believed to have sustained injury as a result of the accident Include 'Stuttard, Janis, Mrs Coach H' Delete ' Stothart, Chloe Helen, Miss Coach C' MlSC 210 HSE BOOKS 0 Crown copyright 2000 Applications for reproduction should be made in writing to: Copyright Unit, Her Majesty's Stationery Office, St Clernents House, 2-16 Colegate, Nofwich NR3 1BQ First published 2000 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. LIST OF CONTENTS Inquiry into Southall Railway Accident Preface Glossary Report Summary PART ONE THE ACCIDENT Chapter l How the accident happened Chapter 2 The emergency response Chapter 3 The track and signals Chapter 4 Why was the freight train crossing? Chapter 5 Driver competence and training Chapter 6 Why were the safety systems not working? Chapter 7 Why the accident happened PART TWO EVENTS SINCE SOUTJULL Chapter 8 The Inquiry and delay to progress Chapter 9 Reactions to Southall Chapter 10 Ladbroke Grove and its aftermath PART THREE WIDER SAFETY ISSUES Chapter 11 Crashworthiness and means of escape Chapter 12 Automatic Warning System (AWS) Chapter 13 Automatic Train Protection (ATP) Chapter 14 Railway Safety Issues PART FOUR CONCLUSION Chapter 15 Discussion and Conclusions Chapter 16 Lessons to be learned Chapter 17 Recommendations ANNEXES THIS Report follows an Inquiry held between September and December 1999 into the cause of a major rail accident which occurred on 19 September 1997 at Southall, 9 miles west of Paddington.