Rifts in Omani Employment Culture: Emerging Joblessness in the Context of Uneven Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Draft Provisonal Agenda and Time-Table

IT/GB-5/13/Inf. 2 June 2013 FIFTH SESSION OF THE GOVERNING BODY Muscat, Oman, 24-28 September 2013 NOTE FOR PARTICIPANTS Last Update: 15 July 2013 1. MEETING ARRANGEMENTS .......................................................................................................... 2 DATE AND PLACE OF THE MEETING ........................................................................................................... 2 COMMUNICATIONS WITH THE SECRETARIAT ........................................................................................... 2 INVITATION LETTERS ................................................................................................................................. 2 ADMISSION OF PARTICIPANTS .................................................................................................................... 2 States that are Contracting Parties ......................................................................................................... 2 States that are not Contracting Parties................................................................................................... 3 Other international bodies or agencies .................................................................................................. 3 2. REGISTRATION ................................................................................................................................. 3 ONLINE PRE-REGISTRATION ..................................................................................................................... -

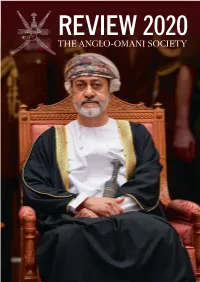

THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY REVIEW 2020 Project Associates’ Business Is to Build, Manage and Protect Our Clients’ Reputations

REVIEW 2020 THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY REVIEW 2020 Project Associates’ business is to build, manage and protect our clients’ reputations. Founded over 20 years ago, we advise corporations, individuals and governments on complex communication issues - issues which are usually at the nexus of the political, business, and media worlds. Our reach, and our experience, is global. We often work on complex issues where traditional models have failed. Whether advising corporates, individuals, or governments, our goal is to achieve maximum targeted impact for our clients. In the midst of a media or political crisis, or when seeking to build a profile to better dominate a new market or subject-area, our role is to devise communication strategies that meet these goals. We leverage our experience in politics, diplomacy and media to provide our clients with insightful counsel, delivering effective results. We are purposefully discerning about the projects we work on, and only pursue those where we can have a real impact. Through our global footprint, with offices in Europe’s major capitals, and in the United States, we are here to help you target the opinions which need to be better informed, and design strategies so as to bring about powerful change. Corporate Practice Private Client Practice Government & Political Project Associates’ Corporate Practice Project Associates’ Private Client Project Associates’ Government helps companies build and enhance Practice provides profile building & Political Practice provides strategic their reputations, in order to ensure and issues and crisis management advisory and public diplomacy their continued licence to operate. for individuals and families. -

Omani Undergraduate Students', Teachers' and Tutors' Metalinguistic

Omani Undergraduate Students’, Teachers’ and Tutors’ Metalinguistic Understanding of Cohesion and Coherence in EFL Academic Writing and their Perspectives of Teaching Cohesion and Coherence Al Siyabi, Jamila Abdullah Kharboosh Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education March 2019 1 Omani Undergraduate Students’, Teachers’ and Tutors’ Metalinguistic Understanding of Cohesion and Coherence in EFL Academic Writing and their Perspectives of Teaching Cohesion and Coherence Submitted by Jamila Abdullah Kharboosh Al Siyabi to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education, March 2019. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (Signed) Jamila 2 ABSTRACT My interpretive study aims to explore how EFL university students verbally articulate their understanding of cohesion and coherence, how they perceive the teaching of cohesion and coherence and how they reflect on the way they have attempted to actualise cohesion and coherence in their EFL academic texts. The study also looks at how their writing teachers and tutors metalinguistically understand cohesion and coherence, and how they perceive issues related to the teaching/tutoring of cohesion and coherence. It has researched the situated realities of students, teachers and tutors through semi-structured interviews, and is informed by Halliday and Hasan’s (1976) taxonomy on cohesion and coherence. -

Paper Submitted by H.E. Malallah Bin Ali Bin Habib Al-Lawati at The

Sultanate of Oman Ministry of National Heritage & Culture Paper submitted by H.E. Malallah bin Ali bin Habib Al-Lawati at the International Seminar of "the Contributions of the Islamic Culture for the Maritime Silk Route" Quanzhou, China, 21-26 February, 1994 International Expedition of "the Islamic Culture along the Coast of China" 27 February - 16 March, 1994 1 Sultanate of Oman Ministry of National Heritage & Culture OMAN AN ENTRÉPOT ON THE MARITIME TRADE ROUTES The Irish explorer Tim Severin in his book 'THE SINDBAD VOYAGE' claims that Omanis have known seafaring ever since man knew the mast and sail. But the recorded history of their negotiation with sea, however, begins in the 3rd millennium BC when Sumerians had settled in northern Oman and mined Copper in Sohar which they called Magan. They sent this copper to the town of Urr in Mesopotamia where they had their headquarters. Apparently the copper was transported by Omani ships. King Sargon of Akkad is said to have praised the Omani ships anchored in an Iraqi Port bringing copper and diorite stones from Magan. The early contact of the Omani People with the sea could be attributed to the following factors:- a) Its location at crossroads between South East Asia, the Middle East and Africa. b) Its long shores extending from Hurmuz Straits on the extreme north down to Yemen - Oman borders. c) Its safe and convenient natural sea-havens for ships. The ports of Muscat, Sohar and Qalhat provided safe shelters plus abundant supplies to ships in all seasons. By virtue of seafaring, Omanis were excellent ship-builders. -

THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY REVIEW 2019 W&S Anglo-Omani-2019-Issue.Indd 1

REVIEW 2019 THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY REVIEW 2019 WWW.WILLIAMANDSON.COM THE PERFECT DESTINATION FOR TOWN & COUNTRY LIVING W&S_Anglo-Omani-2019-Issue.indd 1 19/08/2019 11:51 COVER PHOTO: REVIEW 2019 Jokha Alharthi, winner of the Man Booker International Prize WWW.WILLIAMANDSON.COM THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY CONTENTS 6 CHAIRMAN’S OVERVIEW 62 CHINA’S BELT AND ROAD INITIATIVE 9 NEW WEBSITE FOR THE SOCIETY 64 OMAN AND THE MIDDLE EAST INFRASTRUCTURE BOOM 10 JOKHA ALHARTHI AWARDED THE MAN BOOKER INTERNATIONAL PRIZE 66 THE GULF RESEARCH MEETING AT CAMBRIDGE 13 OLLIE BLAKE’S WEDDING IN CANADA 68 OMAN AND ITS NEIGHBOURS 14 HIGH-LEVEL PARLIAMENTARY EXCHANGES 69 5G NATIONAL WORKING GROUP VISIT TO UK 16 INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON OMANI- 70 OBBC AND OMAN’S VISION 2040 BRITISH RELATIONS IN THE 19TH CENTURY 72 GHAZEER – KHAZZAN PHASE 2 18 ARAB WOMEN AWARD FOR OMANI FORMER MINISTER 74 OLD MUSCAT 20 JOHN CARBIS – OMAN EXPERIENCE 76 OMANI BRITISH LAWYERS ASSOCIATION ANNUAL LONDON RECEPTION 23 THE WORLD’S OLDEST MARINER’S ASTROLABE 77 LONDON ORGAN RECITAL 26 OMAN’S NATURAL HERITAGE LECTURE 2018 79 OUTWARD BOUND OMAN 30 BATS, RODENTS AND SHREWS OF DHOFAR 82 ANGLO-OMANI LUNCHEON 2018 84 WOMEN’S VOICES – THE SOCIETY’S PROGRAMME FOR NEXT YEAR 86 ARABIC LANGUAGE SCHEME 90 GAP YEAR SCHEME REPORT 93 THE SOCIETY’S GRANT SCHEME 94 YOUNG OMANI TEACHERS VISIT BRITISH SCHOOLS 34 ISLANDS IN THE DESERT 96 UNLOCKING THE POTENTIAL OF OMAN’S YOUTH 40 THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF EARLY ISLAM IN OMAN 98 NGG DELEGATION – THE NUDGE FACTOR 44 MILITANT JIHADIST POETRY -

15714 Yenigun 2021 E1.Docx

International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change. www.ijicc.net Volume 15, Issue 7, 2021 The Omani Diaspora in Eastern Africa Cuneyt Yeniguna, Yasir AlRahbib, aAssociate Professor, Director of International Relations and Security Studies Graduate Programs, Founder of Political Science Department, College of Economics and Political Science, Sultan Qaboos University, Muscat, Oman, bOman National Defence College, Sultan Qaboos University, IRSS Graduate Program, M.A. in International Relations, Muscat, Oman. Email: [email protected], [email protected]; [email protected], [email protected] Diasporas play an important role in international relations by connecting homeland and host country. Diasporas can act as a bridge between the sending states and the receiving states in promoting peace and security, and in facilitating economic cooperation between the two sides. Omani people started to settle into Eastern Africa 1300 years ago. It intensified dramatically and reached its peak during the Golden Age of Oman. After Oman lost power and territories in the last century, the natural Omani Diaspora emerged in five different African countries. Perhaps there are millions of Omanis in the region, but the data is not well known. This study concentrates historical background of the Omani Diaspora and today’s Omani Diaspora situation in the region. To understand their current situation in the region, a visit plan was projected and 4 countries and 17 cities were visited, 155 families’ representatives were interviewed with 13 interview questions. In this study, the Omani Diaspora’s tendencies, cultural developments, family relations, home country (Oman) relations, economic situation, political participation, and civil organisational capabilities have been explored. -

Oman's Foreign Policy : Foundations and Practice

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 11-7-2005 Oman's foreign policy : foundations and practice Majid Al-Khalili Florida International University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Al-Khalili, Majid, "Oman's foreign policy : foundations and practice" (2005). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1045. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/1045 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida OMAN'S FOREIGN POLICY: FOUNDATIONS AND PRACTICE A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS by Majid Al-Khalili 2005 To: Interim Dean Mark Szuchman College of Arts and Sciences This dissertation, written by Majid Al-Khalili, and entitled Oman's Foreign Policy: Foundations and Practice, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this dissertation and recommend that it be approved. Dr. Nicholas Onuf Dr. Charles MacDonald Dr. Richard Olson Dr. 1Mohiaddin Mesbahi, Major Professor Date of Defense: November 7, 2005 The dissertation of Majid Al-Khalili is approved. Interim Dean Mark Szuchman C lege of Arts and Scenps Dean ouglas Wartzok University Graduate School Florida International University, 2005 ii @ Copyright 2005 by Majid Al-Khalili All rights reserved. -

Presented by Prime Minister Attends India-Oman Business Meet in Muscat, Oman (February 12, 2018)

Presented by Prime Minister attends India-Oman Business Meet in Muscat, Oman (February 12, 2018) INDIA-OMAN RELATIONS A PRODUCT OF HISTORICAL AND CONTEMPORARY POLITICAL, ECONOMIC AND CULTURAL BONDS By Dr. Lakshmi Priya* ndia and Oman share a strategic and Oman bilateral trade amounts to $ 6.7 billion cordial relationship, well refl ected in their (2017-18). The visit of Indian Prime Minister Imulti-faceted bilateral engagements across Narendra Modi to Oman in February 2018 various fi elds. India as well as Oman have served to further bolster the already warm and respected each other’s sovereignty and share cordial relationship between the two countries. an enduring bond which has only been growing India’s capital New Delhi is geographically stronger with time. closer to Muscat than many Indian cities. The Situated across the Arabian Sea, India is roots of the India-Oman relationship can be Oman’s natural partner with which it has been traced to the 5000 year old maritime trade engaged in trade since ancient times. Oman between the two countries. Oman has been hosts over 800,000 Indian expatriates who bestowed with a topography that isolates it send remittances back home and are a constant within the Arabian Peninsula as well as keeps source of income for India. There are more it secluded from the outside world. The Gulf of than 250 flights per week between Muscat Oman, the Arabian Sea, and the Rub al Khali and Salalah in Oman and a dozen locations in (Empty Quarter) of Saudi Arabia ensure that India. India and Oman conduct regular biennial the only contact that Oman can have with outer bilateral military exercises, and the total India- world is through its water ways. -

Indo–Omani Relations in the Reign of Sultan Taimur Bin Faisal Al Busaidi (1913-1931 AD)

www.ccsenet.org/ach Asian Culture and History Vol. 4, No. 1; January 2012 Indo–Omani Relations in the Reign of Sultan Taimur Bin Faisal Al Busaidi (1913-1931 AD) Dr. Mahmmoud Muhammad Al-Jbarat, Assistant Professor Modern and Contemporary History, Al-Balqa’a Applied University Amman University College for Financial and Administrative Sciences, Jordan E-mail: [email protected] Received: June 8, 2011 Accepted: September 9, 2011 Published: January 1, 2012 doi:10.5539/ach.v4n1p77 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ach.v4n1p77 This article Materials was gathered during 2010-2011 in preparation to participate in the International Conference (Oman and India prospects and civilization) held at sultan Qaboos University from February 27th to March 1st 2011 and the main Ideas were presented in Arabic. Abstract This paper relies on primary resources dealing with the history of Oman along with British documents, which are the most important materials that dealt with the situation in the region, in general, and in Oman in Particular, at a time when Britain had power, presence and military control over India through the Government of British India. At that time, Britain tried to open lines of communication and forge agreements with the Arabian Gulf countries in order to secure its control over this vital region and secure communications with its colonies in India. This study focuses on the economic and commercial relations between the two countries including trade of spices, textile, weapons, slaves, dates and other goods, the currencies used in these commercial exchanges, and the volume of trade. It also explores the volatility of these relations in different periods. -

Evaluating the Resonance of Official Islam in Oman, Jordan, and Morocco

religions Article Evaluating the Resonance of Official Islam in Oman, Jordan, and Morocco Annelle Sheline Middle East Program, The Quincy Institute, Washington, DC 20006, USA; [email protected] Abstract: Acts of political violence carried out by Muslim individuals have generated international support for governments that espouse so-called “moderate Islam” as a means of preventing terrorism. Governments also face domestic skepticism about moderate Islam, especially if the alteration of official Islam is seen as resulting from external pressure. By evaluating the views of individuals that disseminate the state’s preferred interpretation of Islam—members of the religious and educational bureaucracy—this research assesses the variation in the resonance of official Islam in three differ- ent Arab monarchies: Oman, Jordan, and Morocco. The evidence suggests that if official Islam is consistent with earlier content and directed internally as well as externally, it is likely to resonate. Resonance was highest in Oman, as religious messaging about toleration was both consistent over time and directed internally, and lowest in Jordan, where the content shifted and foreign content differed from domestic. In Morocco, messages about toleration were relatively consistent, although the state’s emphasis on building a reputation for toleration somewhat undermined its domestic credibility. The findings have implications for understanding states’ ability to shift their populations’ views on religion, as well as providing greater nuance for interpreting the capacity of state-sponsored rhetoric to prevent violence. Keywords: official Islam; resonance; Oman; Jordan; Morocco Citation: Sheline, Annelle. 2021. Evaluating the Resonance of Official Islam in Oman, Jordan, and Morocco. 1. Introduction Religions 12: 145. -

Health Vision 2050 Sultanate of Oman

�سلـطـنـــــــــة ُعـــــمــان Sultanate of Oman وزارة ال�ســـــــــحــــــة Ministry of Health Health Vision 2050 THE MAIN DOCUMENT Health Vision 2050 The Main Document Prepared by Undersecretariat for Planning Affairs Ministry of Health Sultanate of Oman First Edition May 2014 Health Vision 2050 Sultanate of Oman Contributors Steering Committee Dr Ali Taleb AlHinai, Undersecretary for Planning; Chairman Dr Ahmed Mohamed AlQasmi, Director General of Planning Dr Medhat K. ElSayed, Senior Consultant, Adviser Health Information and Epidemiology Mr Mohamed Hussein Fahmy Bayoumi, Senior Health Information System Supervisor Dr Adhra Hilal Al Mawali, Director of Research and Study Dr Halima Qalm AlHinai, Senior Consultant, Directorate General of Planning Mr Said AlSaidi, Adviser, Studies and Management Development Mr Mohamed Said AlAffifi, Adviser, Office of H.E. Undersecretary for Planning Affaires Strategic Studies Review Team Dr Nazar Abdelrehim Elfaki, Advisor, Human Resources for Health Planning Dr Waleed Khamis AlNadabi, Director Monitoring and Evaluation Other Contributors Dr Mahmoud Attia Abd El Aty, Adviser of Research and Studies Mr Damodaran Yellappan, Senior Health Information System Supervisor International Reviewers Office of the WHO Representative, Oman Dr Abdullah Assaedi, WHO Representative, Sultanate of Oman Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office, WHO (EMRO) Group of Advisors Dr Belgacem Sabri, Ex-Director of Health Systems, EMRO New Zealand Health System Team Professor Des Gorman, Executive Chairman, Health Workforce New Zealand -

Study on Master Plan for Industrial Development in the Sultanate of Oman

No. DIRECTORATE GENERAL OF INDUSTRY, DIRECTORATE GENERAL OF SME DEVELOPMENT, MINISTRY OF COMMERCE AND INDUSTRY, THE SULTANATE OF OMAN STUDYSTUDY ONON MASTERMASTER PLANPLAN FORFOR INDUSTRIALINDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENTDEVELOPMENT ININ THETHE SULTANATESULTANATE OFOF OOMANMAN (SUMMARY)(SUMMARY) FEBRUARY 2010 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY UNICO INTERNATIONAL CORPORATION IDD JR 10-020 Str. of 54 56 Hor 58 60 ° ° mu ° ° Khasab Ra's z OMAN Musandam ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF 26° IRAN Jask- Diba- - al Hisn - PERSIAN GULF Dubayy Madha Al Fujayrah Shinas- GULF OF OMAN Abu Dhabi - Al Liwa'- (Abu Zaby) A - - L Suhar Al Buraymi Saham H - - 24° A Al Khaburah 24° - J Al Qabil A ah As Sib- atr R M - (Masqat) UNITED ARAB EMIRATES Barka' Muscat ank Dank A . D W L - - Bidbid - Afi Qurayyat - G 'Ibri HA - Bahla'- RBI AL H Bimmah Al - AJA Izki R Khuwayr yn AS A Nazwá H - Qalhat S l H - . a A Sur W - R Sanaw Q - Al Hadd ad I sw A Adam . Al Mintirib W W - a - W Al Kamil d - a Al Huwaysah i 22° W H d - As 22° a - a i - Bilad Bani d Suwayh - l M - - i f Bu'Ali m i a l T a Al al y s a h OMAN - Mu n r Ramlat Ashkharah i r - d b Umm as a a - a - al - W m - Samim n - i Wahibah Ra's Jibsh l Sharkh - a Ramlat h al - - - Ra's ar Ru'ays K Ghirbaniyat h SAUDI ARABIA - ra si Filim a l - M Khaluf t - - a Jazirat Masirah a ' r h (Masira) a u - - T Kalban ' m Sirab b h a - 20° u S Hayma' 20° s -is R t a - s la ra - m a Khalij r Ra l H - A at a Duqm Masirah Jidd - r Al 'Aja'iz ta w ARABIAN SEA a h K n W i .