15714 Yenigun 2021 E1.Docx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pre-Colonial States and Separatist Civil Wars

Historical Origins of Modern Ethnic Violence: Pre-Colonial States and Separatist Civil Wars Jack Paine* August 20, 2019 Abstract This paper explains how precolonial statehood has triggered postcolonial ethnic violence. Groups organized as a pre-colonial state (PCS groups) often leveraged their historical privileges to control the postcolonial state while also excluding other ethnic groups from power, creating motives for rebellion. The size of the PCS group determined other groups’ opportunities for either gaining a separate state or overthrowing the government at the center. Regression evidence based on a novel global dataset of historical statehood demonstrates a strong positive correlation between stateless groups in countries with a PCS group and separatist civil war onset. Although the typical PCS group is large enough to deter center-seeking rebellions, in countries where the PCS group is small, stateless groups in their countries fight center-seeking rebellions at high rates. By contrast, particularly large PCS groups disable any rebellion prospects. These findings also explain cross-regional patterns in ethnic civil war onset and aims. *Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, University of Rochester, [email protected]. I thank Bethany Lacina, Alex Lee, and Christy Qiu for helpful comments on earlier drafts. 1 INTRODUCTION Large-scale ethnic conflict is strikingly and tragically common in the postcolonial world. Numerous states outside of Western Europe fit the categorization of weakly institutionalized polities in which armed rebellion provides a viable avenue for aggrieved groups to achieve political goals. Many scholars analyze prospects for powersharing coalitions in these countries and consistently find that ethnic groups that lack access to power in the central government more frequently fight civil wars (Cederman, Gleditsch and Buhaug 2013; Roessler 2016). -

The Harem 19Th-20Th Centuries”

Pt.II: Colonialism, Nationalism, the Harem 19th-20th centuries” Week 10: Nov. 18-22 “Zanzibar – the ‘New Andalous’ Zanzibar: 19th-20th C. (Zanzibar) Zanzibar: 19th-20th C. • Context: requires history of several centuries • Emergence of ‘Swahili’ coast/culture • 16th century with Portuguese conquests • 18th century Omani political/military involvement • 19th century Omani Economic presence Zanzibar: 19th-20th C. • Story ends with in late 19th century: • British and German involvement • Imperial political struggles • Changing global economy • Abolition of Slavery Zanzibar: 19th-20th C. • Story of the Swahili Coast Ocean Trade: Tied East Africa into Arabian and Indian Economies From Medieval Period Zanzibar: 19th-20th C. • Emergence of ‘Swahili’: Trade Winds (Monsoons): Changed direction every Six months Traders forced To remain on East African Coast Zanzibar: 19th-20th C. • Emergence of ‘Swahili’: • Intermarried with African women, established settlements • Built mosques, created Muslim communities • Emergence by 15th century: wealthy ‘Swahili City States’ scattered along coast • Language and culture embracing ‘Indian Ocean World’ Swahili Mosque: 19th-20th C. Zanzibar: 19th-20th C. Zanzibar: 19th-20th C. Swahili Coast: 16th-17th C • Portugal Creating ‘Ocean Empire’: • Following on trans-Atlantic expansion • Developed trade relations with West and Central Africa • Goal: to recapture Indian Ocean and Asian (China) commerce from Muslims • Meant controlling East Africa Portuguese in East Africa Swahili Coast: 16th – 17th C. • 1505: Portuguese successfully sacked Kilwa Swahili Coast: 16th – 17th C. • Established influence along most of coast, built ‘Fort Jesus’ (modern Mozambique) Swahili Coast: 16th – 17th C. • 1552: Portuguese Captured Muscat – Omani Capital Controlled from 1508 – 1650; taken by Persians – retaken by Oman 1741 Swahili Coast: 16th – 17th C. -

Islam and the Abolition of Slavery in the Indian Ocean

Proceedings of the 10th Annual Gilder Lehrman Center International Conference at Yale University Slavery and the Slave Trades in the Indian Ocean and Arab Worlds: Global Connections and Disconnections November 7‐8, 2008 Yale University New Haven, Connecticut Islamic Abolitionism in the Western Indian Ocean from c. 1800 William G. Clarence‐Smith, SOAS, University of London Available online at http://www.yale.edu/glc/indian‐ocean/clarence‐smith.pdf © Do not cite or circulate without the author’s permission For Bernard Lewis, ‘Islamic abolitionism’ is a contradiction in terms, for it was the West that imposed abolition on Islam, through colonial decrees or by exerting pressure on independent states.1 He stands in a long line of weighty scholarship, which stresses the uniquely Western origins of the ending slavery, and the unchallenged legality of slavery in Muslim eyes prior to the advent of modern secularism and socialism. However, there has always been a contrary approach, which recognizes that Islam developed positions hostile to the ‘peculiar institution’ from within its own traditions.2 This paper follows the latter line of thought, exploring Islamic views of slavery in the western Indian Ocean, broadly conceived as stretching from Egypt to India. Islamic abolition was particularly important in turning abolitionist laws into a lived social reality. Muslim rulers were rarely at the forefront of passing abolitionist legislation, 1 Bernard Lewis, Race and slavery in the Middle East, an historical enquiry (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990) pp. 78‐84. Clarence‐Smith 1 and, if they were, they often failed to enforce laws that were ‘for the Englishman to see.’ Legislation was merely the first step, for it proved remarkably difficult to suppress the slave trade, let alone slavery itself, in the western Indian Ocean.3 Only when the majority of Muslims, including slaves themselves, embraced the process of reform did social relations really change on the ground. -

Draft Provisonal Agenda and Time-Table

IT/GB-5/13/Inf. 2 June 2013 FIFTH SESSION OF THE GOVERNING BODY Muscat, Oman, 24-28 September 2013 NOTE FOR PARTICIPANTS Last Update: 15 July 2013 1. MEETING ARRANGEMENTS .......................................................................................................... 2 DATE AND PLACE OF THE MEETING ........................................................................................................... 2 COMMUNICATIONS WITH THE SECRETARIAT ........................................................................................... 2 INVITATION LETTERS ................................................................................................................................. 2 ADMISSION OF PARTICIPANTS .................................................................................................................... 2 States that are Contracting Parties ......................................................................................................... 2 States that are not Contracting Parties................................................................................................... 3 Other international bodies or agencies .................................................................................................. 3 2. REGISTRATION ................................................................................................................................. 3 ONLINE PRE-REGISTRATION ..................................................................................................................... -

Moorings: Indian Ocean Trade and the State in East Africa

MOORINGS: INDIAN OCEAN TRADE AND THE STATE IN EAST AFRICA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Nidhi Mahajan August 2015 © 2015 Nidhi Mahajan MOORINGS: INDIAN OCEAN TRADE AND THE STATE IN EAST AFRICA Nidhi Mahajan, Ph. D. Cornell University 2015 Ever since the 1998 bombings of American embassies in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam, especially post - 9/11 and the “War on Terror,” the Kenyan coast and the Indian Ocean beyond have become flashpoints for national and international security. The predominantly Muslim sailors, merchants, and residents of the coast, with transnational links to Somalia, the Middle East, and South Asia have increasingly become the object of suspicion. Governments and media alike assume that these longstanding transnational linkages, especially in the historical sailing vessel or dhow trade, are entwined with networks of terror. This study argues that these contemporary security concerns gesture to an anxiety over the coast’s long history of trade and social relations across the Indian Ocean and inland Africa. At the heart of these tensions are competing notions of sovereignty and territoriality, as sovereign nation-states attempt to regulate and control trades that have historically implicated polities that operated on a loose, shared, and layered notion of sovereignty and an “itinerant territoriality.” Based on over twenty-two months of archival and ethnographic research in Kenya and India, this dissertation examines state attempts to regulate Indian Ocean trade, and the manner in which participants in these trades maneuver regulatory regimes. -

The Omani Empire and the Development of East Africa

International Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Studies Volume 6, Issue 7, 2019, PP 25-30 ISSN 2394-6288 (Print) & ISSN 2394-6296 (Online) The Omani Empire and the Development of East Africa ABOH, JAMES A1*, NTUI, DANIEL OKORN2, PATRICK O. ODEY3 1&3Department of History and International Studies, University of Calabar, Calabar,Nigeria. 2INEC, Akwa Ibom State,Nigeria. *Corresponding Author: ABOH, JAMES A, Department of History and International Studies, University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigerai. Email:[email protected] ABSTRACT The East African coast had extensive interaction with other regions and races in the world. One of these groups was the Omani Arabs who were pulled to the coastline of East Africa for commercial expansion, the serenity of the environment and the fertility of the soil. The Omani Sultan had ruled the empire from Muscat but later relocated the capital to Zanzibar. This paper examines the impact of the Omani Empire on the economic, socio-cultural and political development of East Africa. It was observed that with the interactions that first began along the coastlines of East Africa some coastal city-states like Pemba, Malindi, Mozambique, Sofia, Kilwa, Mombasa, and Zanzibar emerged. The Omani Arabs under the leadership of Sultan Sayyid Said introduced the caravan trade, custom duties, credit facility for investment, and the invention of a hybrid of language and culture- Swahili/Kswahili. Nevertheless, the innovations introduced into the east coast of Africa were intended to fulfill the commercial mandate of the Arabs leaving Africans as passive and/or unequal participants in the scheme of things, given the meddlesomeness of the Arabs in the internal affairs of the East Africans leading to conflicts that continue to hunt the region. -

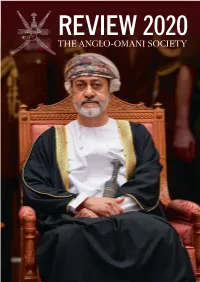

THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY REVIEW 2020 Project Associates’ Business Is to Build, Manage and Protect Our Clients’ Reputations

REVIEW 2020 THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY REVIEW 2020 Project Associates’ business is to build, manage and protect our clients’ reputations. Founded over 20 years ago, we advise corporations, individuals and governments on complex communication issues - issues which are usually at the nexus of the political, business, and media worlds. Our reach, and our experience, is global. We often work on complex issues where traditional models have failed. Whether advising corporates, individuals, or governments, our goal is to achieve maximum targeted impact for our clients. In the midst of a media or political crisis, or when seeking to build a profile to better dominate a new market or subject-area, our role is to devise communication strategies that meet these goals. We leverage our experience in politics, diplomacy and media to provide our clients with insightful counsel, delivering effective results. We are purposefully discerning about the projects we work on, and only pursue those where we can have a real impact. Through our global footprint, with offices in Europe’s major capitals, and in the United States, we are here to help you target the opinions which need to be better informed, and design strategies so as to bring about powerful change. Corporate Practice Private Client Practice Government & Political Project Associates’ Corporate Practice Project Associates’ Private Client Project Associates’ Government helps companies build and enhance Practice provides profile building & Political Practice provides strategic their reputations, in order to ensure and issues and crisis management advisory and public diplomacy their continued licence to operate. for individuals and families. -

University of London Oman and the West

University of London Oman and the West: State Formation in Oman since 1920 A thesis submitted to the London School of Economics and Political Science in candidacy for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Francis Carey Owtram 1999 UMI Number: U126805 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U126805 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 bLOSiL ZZLL d ABSTRACT This thesis analyses the external and internal influences on the process of state formation in Oman since 1920 and places this process in comparative perspective with the other states of the Gulf Cooperation Council. It considers the extent to which the concepts of informal empire and collaboration are useful in analysing the relationship between Oman, Britain and the United States. The theoretical framework is the historical materialist paradigm of International Relations. State formation in Oman since 1920 is examined in a historical narrative structured by three themes: (1) the international context of Western involvement, (2) the development of Western strategic interests in Oman and (3) their economic, social and political impact on Oman. -

Rifts in Omani Employment Culture: Emerging Joblessness in the Context of Uneven Development

Rifts in Omani Employment Culture: Emerging Joblessness in the Context of Uneven Development. The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Al-Hashmi, Julanda S. H. 2019. Rifts in Omani Employment Culture: Emerging Joblessness in the Context of Uneven Development.. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42004191 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Rifts in Omani Employment Culture: Emerging Joblessness in the Context of Uneven Development. A Julanda S. H. Al-Hashmi A Thesis in the Field of Government for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University March 2019 Copyright ! Julanda Al-Hashmi 2019 Abstract Beginning in 1970, Oman experienced modernization at a rapid pace due to the discovery of oil. At that time, the country still had not invested much in infrastructure development, and a large part of the national population had low levels of literacy as they lacked formal education. For these reasons, the national workforce was unable to fuel the growing oil and gas sector, and the Omani government found it necessary to import foreign labor during the 1970s. Over the ensuing decades, however, the reliance on foreign labor has remained and has led to sharp labor market imbalances. Today the foreign-born population is 45 percent of Oman’s total population and makes up an overwhelming 89 percent of the private sector workforce. -

A Study of Ibadi Oman

UCLA Journal of Religion Volume 2 2018 Developing Tolerance and Conservatism: A Study of Ibadi Oman Connor D. Elliott The George Washington University ABSTRACT This thesis analyzes the development of Omani-Ibadi society from pre- Islam to the present day. Oman represents an anomaly in the religious world because its Ibadi theology is conservative in nature while also preaching unwavering tolerance. To properly understand how Oman developed such a unique culture and religion, it is necessary to historically analyze the country by recounting the societal developments that occurred throughout the millennia. By doing so, one begins to understand that Oman did not achieve this peaceful religious theology over the past couple of decades. Oman has an exceptional society that was built out of longtime traditions like a trade-based economy that required foreign interaction, long periods of political sovereignty or autonomy, and a unique theology. The Omani-Ibadi people and their leaders have continuously embraced the ancient roots of their regional and religious traditions to create a contemporary state that espouses a unique society that leads people to live conservative personal lives while exuding outward tolerance. Keywords: Oman, Ibadi, Tolerance, Theology, History, Sociology UCLA Journal of Religion Vol. 2, 2018 Developing Tolerance and Conservatism: A Study of Ibadi Oman By Connor D. Elliott1 The George Washington University INTRODUCTION he Sultanate of Oman is a country which consistently draws acclaim T for its tolerance and openness towards peoples of varying faiths. The sect of Islam most Omanis follow, Ibadiyya, is almost entirely unique to Oman with over 2 million of the 2.5 million Ibadis worldwide found in the sultanate.2 This has led many to see the Omani government as the de facto state-representative of Ibadiyya in contemporary times. -

Omani Undergraduate Students', Teachers' and Tutors' Metalinguistic

Omani Undergraduate Students’, Teachers’ and Tutors’ Metalinguistic Understanding of Cohesion and Coherence in EFL Academic Writing and their Perspectives of Teaching Cohesion and Coherence Al Siyabi, Jamila Abdullah Kharboosh Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education March 2019 1 Omani Undergraduate Students’, Teachers’ and Tutors’ Metalinguistic Understanding of Cohesion and Coherence in EFL Academic Writing and their Perspectives of Teaching Cohesion and Coherence Submitted by Jamila Abdullah Kharboosh Al Siyabi to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education, March 2019. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (Signed) Jamila 2 ABSTRACT My interpretive study aims to explore how EFL university students verbally articulate their understanding of cohesion and coherence, how they perceive the teaching of cohesion and coherence and how they reflect on the way they have attempted to actualise cohesion and coherence in their EFL academic texts. The study also looks at how their writing teachers and tutors metalinguistically understand cohesion and coherence, and how they perceive issues related to the teaching/tutoring of cohesion and coherence. It has researched the situated realities of students, teachers and tutors through semi-structured interviews, and is informed by Halliday and Hasan’s (1976) taxonomy on cohesion and coherence. -

Paper Submitted by H.E. Malallah Bin Ali Bin Habib Al-Lawati at The

Sultanate of Oman Ministry of National Heritage & Culture Paper submitted by H.E. Malallah bin Ali bin Habib Al-Lawati at the International Seminar of "the Contributions of the Islamic Culture for the Maritime Silk Route" Quanzhou, China, 21-26 February, 1994 International Expedition of "the Islamic Culture along the Coast of China" 27 February - 16 March, 1994 1 Sultanate of Oman Ministry of National Heritage & Culture OMAN AN ENTRÉPOT ON THE MARITIME TRADE ROUTES The Irish explorer Tim Severin in his book 'THE SINDBAD VOYAGE' claims that Omanis have known seafaring ever since man knew the mast and sail. But the recorded history of their negotiation with sea, however, begins in the 3rd millennium BC when Sumerians had settled in northern Oman and mined Copper in Sohar which they called Magan. They sent this copper to the town of Urr in Mesopotamia where they had their headquarters. Apparently the copper was transported by Omani ships. King Sargon of Akkad is said to have praised the Omani ships anchored in an Iraqi Port bringing copper and diorite stones from Magan. The early contact of the Omani People with the sea could be attributed to the following factors:- a) Its location at crossroads between South East Asia, the Middle East and Africa. b) Its long shores extending from Hurmuz Straits on the extreme north down to Yemen - Oman borders. c) Its safe and convenient natural sea-havens for ships. The ports of Muscat, Sohar and Qalhat provided safe shelters plus abundant supplies to ships in all seasons. By virtue of seafaring, Omanis were excellent ship-builders.