The Harem 19Th-20Th Centuries”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pre-Colonial States and Separatist Civil Wars

Historical Origins of Modern Ethnic Violence: Pre-Colonial States and Separatist Civil Wars Jack Paine* August 20, 2019 Abstract This paper explains how precolonial statehood has triggered postcolonial ethnic violence. Groups organized as a pre-colonial state (PCS groups) often leveraged their historical privileges to control the postcolonial state while also excluding other ethnic groups from power, creating motives for rebellion. The size of the PCS group determined other groups’ opportunities for either gaining a separate state or overthrowing the government at the center. Regression evidence based on a novel global dataset of historical statehood demonstrates a strong positive correlation between stateless groups in countries with a PCS group and separatist civil war onset. Although the typical PCS group is large enough to deter center-seeking rebellions, in countries where the PCS group is small, stateless groups in their countries fight center-seeking rebellions at high rates. By contrast, particularly large PCS groups disable any rebellion prospects. These findings also explain cross-regional patterns in ethnic civil war onset and aims. *Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, University of Rochester, [email protected]. I thank Bethany Lacina, Alex Lee, and Christy Qiu for helpful comments on earlier drafts. 1 INTRODUCTION Large-scale ethnic conflict is strikingly and tragically common in the postcolonial world. Numerous states outside of Western Europe fit the categorization of weakly institutionalized polities in which armed rebellion provides a viable avenue for aggrieved groups to achieve political goals. Many scholars analyze prospects for powersharing coalitions in these countries and consistently find that ethnic groups that lack access to power in the central government more frequently fight civil wars (Cederman, Gleditsch and Buhaug 2013; Roessler 2016). -

Islam and the Abolition of Slavery in the Indian Ocean

Proceedings of the 10th Annual Gilder Lehrman Center International Conference at Yale University Slavery and the Slave Trades in the Indian Ocean and Arab Worlds: Global Connections and Disconnections November 7‐8, 2008 Yale University New Haven, Connecticut Islamic Abolitionism in the Western Indian Ocean from c. 1800 William G. Clarence‐Smith, SOAS, University of London Available online at http://www.yale.edu/glc/indian‐ocean/clarence‐smith.pdf © Do not cite or circulate without the author’s permission For Bernard Lewis, ‘Islamic abolitionism’ is a contradiction in terms, for it was the West that imposed abolition on Islam, through colonial decrees or by exerting pressure on independent states.1 He stands in a long line of weighty scholarship, which stresses the uniquely Western origins of the ending slavery, and the unchallenged legality of slavery in Muslim eyes prior to the advent of modern secularism and socialism. However, there has always been a contrary approach, which recognizes that Islam developed positions hostile to the ‘peculiar institution’ from within its own traditions.2 This paper follows the latter line of thought, exploring Islamic views of slavery in the western Indian Ocean, broadly conceived as stretching from Egypt to India. Islamic abolition was particularly important in turning abolitionist laws into a lived social reality. Muslim rulers were rarely at the forefront of passing abolitionist legislation, 1 Bernard Lewis, Race and slavery in the Middle East, an historical enquiry (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990) pp. 78‐84. Clarence‐Smith 1 and, if they were, they often failed to enforce laws that were ‘for the Englishman to see.’ Legislation was merely the first step, for it proved remarkably difficult to suppress the slave trade, let alone slavery itself, in the western Indian Ocean.3 Only when the majority of Muslims, including slaves themselves, embraced the process of reform did social relations really change on the ground. -

Moorings: Indian Ocean Trade and the State in East Africa

MOORINGS: INDIAN OCEAN TRADE AND THE STATE IN EAST AFRICA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Nidhi Mahajan August 2015 © 2015 Nidhi Mahajan MOORINGS: INDIAN OCEAN TRADE AND THE STATE IN EAST AFRICA Nidhi Mahajan, Ph. D. Cornell University 2015 Ever since the 1998 bombings of American embassies in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam, especially post - 9/11 and the “War on Terror,” the Kenyan coast and the Indian Ocean beyond have become flashpoints for national and international security. The predominantly Muslim sailors, merchants, and residents of the coast, with transnational links to Somalia, the Middle East, and South Asia have increasingly become the object of suspicion. Governments and media alike assume that these longstanding transnational linkages, especially in the historical sailing vessel or dhow trade, are entwined with networks of terror. This study argues that these contemporary security concerns gesture to an anxiety over the coast’s long history of trade and social relations across the Indian Ocean and inland Africa. At the heart of these tensions are competing notions of sovereignty and territoriality, as sovereign nation-states attempt to regulate and control trades that have historically implicated polities that operated on a loose, shared, and layered notion of sovereignty and an “itinerant territoriality.” Based on over twenty-two months of archival and ethnographic research in Kenya and India, this dissertation examines state attempts to regulate Indian Ocean trade, and the manner in which participants in these trades maneuver regulatory regimes. -

The Omani Empire and the Development of East Africa

International Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Studies Volume 6, Issue 7, 2019, PP 25-30 ISSN 2394-6288 (Print) & ISSN 2394-6296 (Online) The Omani Empire and the Development of East Africa ABOH, JAMES A1*, NTUI, DANIEL OKORN2, PATRICK O. ODEY3 1&3Department of History and International Studies, University of Calabar, Calabar,Nigeria. 2INEC, Akwa Ibom State,Nigeria. *Corresponding Author: ABOH, JAMES A, Department of History and International Studies, University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigerai. Email:[email protected] ABSTRACT The East African coast had extensive interaction with other regions and races in the world. One of these groups was the Omani Arabs who were pulled to the coastline of East Africa for commercial expansion, the serenity of the environment and the fertility of the soil. The Omani Sultan had ruled the empire from Muscat but later relocated the capital to Zanzibar. This paper examines the impact of the Omani Empire on the economic, socio-cultural and political development of East Africa. It was observed that with the interactions that first began along the coastlines of East Africa some coastal city-states like Pemba, Malindi, Mozambique, Sofia, Kilwa, Mombasa, and Zanzibar emerged. The Omani Arabs under the leadership of Sultan Sayyid Said introduced the caravan trade, custom duties, credit facility for investment, and the invention of a hybrid of language and culture- Swahili/Kswahili. Nevertheless, the innovations introduced into the east coast of Africa were intended to fulfill the commercial mandate of the Arabs leaving Africans as passive and/or unequal participants in the scheme of things, given the meddlesomeness of the Arabs in the internal affairs of the East Africans leading to conflicts that continue to hunt the region. -

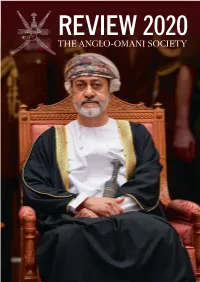

THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY REVIEW 2020 Project Associates’ Business Is to Build, Manage and Protect Our Clients’ Reputations

REVIEW 2020 THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY REVIEW 2020 Project Associates’ business is to build, manage and protect our clients’ reputations. Founded over 20 years ago, we advise corporations, individuals and governments on complex communication issues - issues which are usually at the nexus of the political, business, and media worlds. Our reach, and our experience, is global. We often work on complex issues where traditional models have failed. Whether advising corporates, individuals, or governments, our goal is to achieve maximum targeted impact for our clients. In the midst of a media or political crisis, or when seeking to build a profile to better dominate a new market or subject-area, our role is to devise communication strategies that meet these goals. We leverage our experience in politics, diplomacy and media to provide our clients with insightful counsel, delivering effective results. We are purposefully discerning about the projects we work on, and only pursue those where we can have a real impact. Through our global footprint, with offices in Europe’s major capitals, and in the United States, we are here to help you target the opinions which need to be better informed, and design strategies so as to bring about powerful change. Corporate Practice Private Client Practice Government & Political Project Associates’ Corporate Practice Project Associates’ Private Client Project Associates’ Government helps companies build and enhance Practice provides profile building & Political Practice provides strategic their reputations, in order to ensure and issues and crisis management advisory and public diplomacy their continued licence to operate. for individuals and families. -

University of London Oman and the West

University of London Oman and the West: State Formation in Oman since 1920 A thesis submitted to the London School of Economics and Political Science in candidacy for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Francis Carey Owtram 1999 UMI Number: U126805 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U126805 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 bLOSiL ZZLL d ABSTRACT This thesis analyses the external and internal influences on the process of state formation in Oman since 1920 and places this process in comparative perspective with the other states of the Gulf Cooperation Council. It considers the extent to which the concepts of informal empire and collaboration are useful in analysing the relationship between Oman, Britain and the United States. The theoretical framework is the historical materialist paradigm of International Relations. State formation in Oman since 1920 is examined in a historical narrative structured by three themes: (1) the international context of Western involvement, (2) the development of Western strategic interests in Oman and (3) their economic, social and political impact on Oman. -

A Study of Ibadi Oman

UCLA Journal of Religion Volume 2 2018 Developing Tolerance and Conservatism: A Study of Ibadi Oman Connor D. Elliott The George Washington University ABSTRACT This thesis analyzes the development of Omani-Ibadi society from pre- Islam to the present day. Oman represents an anomaly in the religious world because its Ibadi theology is conservative in nature while also preaching unwavering tolerance. To properly understand how Oman developed such a unique culture and religion, it is necessary to historically analyze the country by recounting the societal developments that occurred throughout the millennia. By doing so, one begins to understand that Oman did not achieve this peaceful religious theology over the past couple of decades. Oman has an exceptional society that was built out of longtime traditions like a trade-based economy that required foreign interaction, long periods of political sovereignty or autonomy, and a unique theology. The Omani-Ibadi people and their leaders have continuously embraced the ancient roots of their regional and religious traditions to create a contemporary state that espouses a unique society that leads people to live conservative personal lives while exuding outward tolerance. Keywords: Oman, Ibadi, Tolerance, Theology, History, Sociology UCLA Journal of Religion Vol. 2, 2018 Developing Tolerance and Conservatism: A Study of Ibadi Oman By Connor D. Elliott1 The George Washington University INTRODUCTION he Sultanate of Oman is a country which consistently draws acclaim T for its tolerance and openness towards peoples of varying faiths. The sect of Islam most Omanis follow, Ibadiyya, is almost entirely unique to Oman with over 2 million of the 2.5 million Ibadis worldwide found in the sultanate.2 This has led many to see the Omani government as the de facto state-representative of Ibadiyya in contemporary times. -

The Harem 19Th-20Th Centuries”

Pt.II: Colonialism, Nationalism, the Harem 19th-20th centuries” Week 10: Nov. 18-22 “Zanzibar – the ‘New Andalous’ Zanzibar: 19th-20th C. (Zanzibar) Zanzibar: 19th-20th C. • Context: requires history of several centuries • Emergence of ‘Swahili’ coast/culture • 16th century with Portuguese conquests • 18th century Omani political/military involvement • 19th century Omani Economic presence Zanzibar: 19th-20th C. • Story ends with in late 19th century: • British and German involvement • Imperial political struggles • Changing global economy • Abolition of Slavery Zanzibar: 19th-20th C. • Story of the Swahili Coast Ocean Trade: Tied East Africa into Arabian and Indian Economies From Medieval Period Zanzibar: 19th-20th C. • Emergence of ‘Swahili’: Trade Winds (Monsoons): Changed direction every Six months Traders forced To remain on East African Coast Zanzibar: 19th-20th C. • Emergence of ‘Swahili’: • Intermarried with African women, established settlements • Built mosques, created Muslim communities • Emergence by 15th century: wealthy ‘Swahili City States’ scattered along coast • Language and culture embracing ‘Indian Ocean World’ Swahili Mosque: 19th-20th C. Zanzibar: 19th-20th C. Zanzibar: 19th-20th C. Swahili Coast: 16th-17th C • Portugal Creating ‘Ocean Empire’: • Following on trans-Atlantic expansion • Developed trade relations with West and Central Africa • Goal: to recapture Indian Ocean and Asian (China) commerce from Muslims • Meant controlling East Africa Portuguese in East Africa Swahili Coast: 16th –17th C. • 1505: Portuguese successfully sacked Kilwa Swahili Coast: 16th –17th C. • Established influence along most of coast, built ‘Fort Jesus’ (modern Mozambique) Swahili Coast: 16th –17th C. • 1552: Portuguese Captured Muscat – Omani Capital Controlled from 1508 – 1650; taken by Persians – retaken by Oman 1741 Swahili Coast: 16th –17th C. -

15714 Yenigun 2021 E1.Docx

International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change. www.ijicc.net Volume 15, Issue 7, 2021 The Omani Diaspora in Eastern Africa Cuneyt Yeniguna, Yasir AlRahbib, aAssociate Professor, Director of International Relations and Security Studies Graduate Programs, Founder of Political Science Department, College of Economics and Political Science, Sultan Qaboos University, Muscat, Oman, bOman National Defence College, Sultan Qaboos University, IRSS Graduate Program, M.A. in International Relations, Muscat, Oman. Email: [email protected], [email protected]; [email protected], [email protected] Diasporas play an important role in international relations by connecting homeland and host country. Diasporas can act as a bridge between the sending states and the receiving states in promoting peace and security, and in facilitating economic cooperation between the two sides. Omani people started to settle into Eastern Africa 1300 years ago. It intensified dramatically and reached its peak during the Golden Age of Oman. After Oman lost power and territories in the last century, the natural Omani Diaspora emerged in five different African countries. Perhaps there are millions of Omanis in the region, but the data is not well known. This study concentrates historical background of the Omani Diaspora and today’s Omani Diaspora situation in the region. To understand their current situation in the region, a visit plan was projected and 4 countries and 17 cities were visited, 155 families’ representatives were interviewed with 13 interview questions. In this study, the Omani Diaspora’s tendencies, cultural developments, family relations, home country (Oman) relations, economic situation, political participation, and civil organisational capabilities have been explored. -

University of Leeds School of Politics and International Studies (POLIS)

State, Religion and Democracy in the Sultanate of Oman Sulaiman H. AI-Farsi Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Politics and International Studies (POLIS) June,2010 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. UNIVERSITY OF LEEDS Acknowledgements This thesis is gratefully dedicated in particular to my marvellous supervisors, Professor Clive Jones and Dr. Caroline Dyer for their unparalleled support throughout the study period; for their serenity in reading my successive drafts; for their invaluable advice, comments, and prompt responses; for their immeasurable time expended and for their care and sympathy during trying times. lowe a great debt of gratitude to the University of Leeds for its excellent research resources and environment; for its libraries, the SDDU, the ISS and all staff in the POLIS department, and particularly the most patient and dynamic Helen Philpott. I am also greatly indebted to my beloved country, Oman, for everything, including the scholarship offered to me to do this research; to the members of my family who continued to support me throughout this study, particularly my wife who has taken on all the responsibilities of looking after the house and children; to my children (Maeen, Hamed, Ahmed and Mohammed) for understanding why I was away from them despite their young ages, and my brothers (Abdullah and Mohammed) who backed me and looked after my family. -

2B-1. Homework-Person 1

Oman’s History Oman has been inhabited since pre-historic times. Because of its important strategic location, it has been a major trading country since the 6th century BCE – though it was often dominated by other peoples (Persians, Babylonians, etc.). After the coming of Islam, the area was ruled by religious leaders (imams) and then by hereditary kings. With the growth of European influence in the area, the Portuguese took control of Oman and the surrounding areas, ruling through the 16th and part of the 17th centuries. By the mid- 1600s, however, Oman was gradually gaining independence; by 1698, Oman had also taken control of Zanzibar (2000 miles away, but easily accessible by sea thanks to the monsoon winds) and other parts of East Africa. Zanzibar became such an important part of the Omani Empire that for a few decades in the mid-19th century, the Sultan of Oman actually moved to the island and ruled from there. By the 1860s, however, the two areas were ruled by different branches of the same Omani royal family; by the 1890s, the British seized Zanzibar, permanently severing the political link between Zanzibar and Oman. The 20th century saw Oman begin to modernize. In the 1950s, the sultan had to put down a revolt led by the Muslim religious leader (imam) of Nizwa, while in the 1960s, the government had to fight a communist-led rebellion in the Dhofar region, which borders Yemen. The Omani government eventually was successful in putting down both revolts. In 1970, the current sultan, Sultan Qaboos, came to power by ousting his father, who went into exile. -

The Imperial Roots of Global Trade ∗

The Imperial Roots of Global Trade ∗ Gunes Gokmeny Wessel N. Vermeulenz Pierre-Louis V´ezinax October 11, 2017 Abstract Today's countries emerged from hundreds of years of conquests, alliances and downfalls of empires. Empires facilitated trade within their controlled territories by building and securing trade and migration routes, and by imposing common norms, languages, religions, and legal systems, all of which led to the accumulation of trading capital. In this paper, we uncover how the rise and fall of empires over the last 5,000 years still influence world trade. We collect novel data on 5,000 years of imperial history of countries, construct a measure of accumulated trading capital between countries, and estimate its effect on trade patterns today. Our measure of trading capital has a positive and significant effect on trade that survives controlling for potential historical mechanisms such as sharing a language, a religion, genes, a legal system, and for the ease of natural trade and invasion routes. This suggests a persistent and previously unexplained effect of long-gone empires on trade. JEL CODES: F14, N70 Key Words: long run, persistence, empires, trading capital, gravity. ∗We are grateful to Danila Smirnov for excellent research assistance and to Roberto Bonfatti, Anton Howes, Vania Licio, and seminar participants at the 2016 Canadian Economic Association Annual Meeting in Ottawa, King's College London, and the 2017 FREIT Workshop in Cagliari for their constructive comments. yNew Economic School and the Center for the Study of Diversity and Social Interactions, Moscow. Email: [email protected]. Gokmen acknowledges the support of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation, grant No.