Imes Capstone Paper Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amir Mourns H M Sultan Qaboos

www.thepeninsula.qa Volume 24 | Number 8134 SUNDAY 12 JANUARY 2020 17 JUMADA I - 1441 2 RIYALS BUSINESS | 17 SPORT | 24 ARTIC expands Rublev wins operational Qatar hotel portfolio ExxonMobil in Qatar Open Enjoy unlimited local data and calls with the new Qatarna 5G plans Amir, Putin hold phone talks, Amir mourns H M Sultan Qaboos discuss regional Qatar announces ‘Oman to continue path developments three days of QNA — DOHA mourning This is a sad day for all the Gulf people, as for the laid by Sultan Qaboos’ brothers in Oman. With great sorrow, we received in Amir H H Sheikh Tamim bin Qatar the news of the departure of Sultan Qaboos to the QNA — MUSCAT set by the late H M Sultan Hamad Al Thani held a tele- QNA — DOHA mercy of Allah The Almighty, leaving behind a rising Qaboos in bolstering cooper- phone conversation yesterday country and a great legacy that everyone cherishes. It is H M Sultan Haitham bin ation with brothers in the GCC with H E President Vladimir Amir H H Sheikh Tamim bin a great loss for the Arab and Islamic nations. We offer Tariq bin Taimur Al Said was and the Arab world without Putin of the friendly Russian Hamad Al Thani mourned condolences to the brotherly Omani people and we pray announced as the new Sultan interfering in the affairs of Federation. yesterday the death of H M to Allah for His Majesty the Supreme Paradise. of Oman, in succession to the others. Peace and coexistence During the phone call, they Sultan Qaboos bin Said bin late H M Sultan Qaboos bin will remain as cornerstones of discussed a number of regional Taimur of the Sultanate of and international issues of Oman, who passed away on common concern, especially Friday evening. -

Latorre 8840 SP13.Pdf

WS 8840 Topics in Representing Gender Nation and Gender in Latin American Visual Culture Professor Guisela Latorre Class time: Tuesdays 11:15-2:00pm Phone: 247-7720 Classroom: 286 University Hall Email: [email protected] Office: 286H University Hall Office Hours: Thursdays 11-1pm or by appointment Course Description For the past three decades, scholars in the fields of gender, ethnic, and cultural studies, among other disciplines, have insisted upon the critical role that gendered ideologies play in the formation of nationalist discourses, myths and paradigms. Given its history of colonialism and imperialism but also hybridity and mestizaje, Latin America has emerged as a rich and complicated breeding ground for national and nationalist rhetorics that are deeply steeped in notions of femininity, masculinity, and other gendered constructs. While gendered nationalist tropes have been forged through various social and political means in Latin America, visual cultural production in its many forms has been a powerful vehicle through which these ideologies are promoted, disseminated and inscribed upon the social psyche. This graduate seminar is thus dedicated to the perilous history of gender, nation and visual culture in Latin America. Art, film, and mass media, among other visual “artifacts”, will be at the center of our discussions, queries and debates in class this quarter. We will explore varied and diverse themes such as the following: 1) casta paintings and their role in the formation of New Spain’s colonial state, 2) Eva Perón or Evita as a national icon in Argentina, 3) telenovelas and cultural identity in Brazil and Mexico, and many others. -

Protest and State–Society Relations in the Middle East and North Africa

SIPRI Policy Paper PROTEST AND STATE– 56 SOCIETY RELATIONS IN October 2020 THE MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA dylan o’driscoll, amal bourhrous, meray maddah and shivan fazil STOCKHOLM INTERNATIONAL PEACE RESEARCH INSTITUTE SIPRI is an independent international institute dedicated to research into conflict, armaments, arms control and disarmament. Established in 1966, SIPRI provides data, analysis and recommendations, based on open sources, to policymakers, researchers, media and the interested public. The Governing Board is not responsible for the views expressed in the publications of the Institute. GOVERNING BOARD Ambassador Jan Eliasson, Chair (Sweden) Dr Vladimir Baranovsky (Russia) Espen Barth Eide (Norway) Jean-Marie Guéhenno (France) Dr Radha Kumar (India) Ambassador Ramtane Lamamra (Algeria) Dr Patricia Lewis (Ireland/United Kingdom) Dr Jessica Tuchman Mathews (United States) DIRECTOR Dan Smith (United Kingdom) Signalistgatan 9 SE-169 72 Solna, Sweden Telephone: + 46 8 655 9700 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.sipri.org Protest and State– Society Relations in the Middle East and North Africa SIPRI Policy Paper No. 56 dylan o’driscoll, amal bourhrous, meray maddah and shivan fazil October 2020 © SIPRI 2020 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of SIPRI or as expressly permitted by law. Contents Preface v Acknowledgements vi Summary vii Abbreviations ix 1. Introduction 1 Figure 1.1. Classification of countries in the Middle East and North Africa by 2 protest intensity 2. State–society relations in the Middle East and North Africa 5 Mass protests 5 Sporadic protests 16 Scarce protests 31 Highly suppressed protests 37 Figure 2.1. -

"El Indio" Fernández: Myth, Mestizaje, and Modern Mexico

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2009-08-10 The Indigenismo of Emilio "El Indio" Fernández: Myth, Mestizaje, and Modern Mexico Mathew J. K. HILL Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Spanish and Portuguese Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation HILL, Mathew J. K., "The Indigenismo of Emilio "El Indio" Fernández: Myth, Mestizaje, and Modern Mexico" (2009). Theses and Dissertations. 1915. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/1915 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. THE INDIGENISMO OF EMILIO “EL INDIO” FERNÁNDEZ: MYTH, MESTIZAJE, AND MODERN MEXICO by Matthew JK Hill A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Spanish and Portuguese Brigham Young University December 2009 Copyright © 2009 Matthew JK Hill All Rights Reserved BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COMMITTEE APPROVAL of a thesis submitted by Matthew JK Hill This thesis has been read by each member of the following graduate committee and by majority vote has been found to be satisfactory. Date Douglas J. Weatherford, Chair Date Russell M. Cluff Date David Laraway BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY As chair of the candidate’s graduate committee, I have read the thesis of Matthew JK Hill in its final form and have found that (1) its format, citations, and bibliographical style are consistent and acceptable and fulfill university and department style requirements; (2) its illustrative materials including figures, tables, and charts are in place; and (3) the final manuscript is satisfactory to the graduate committee and is ready for submission to the university library. -

Car Decals, Civic Rituals, and Changing Conceptions of Nationalism

International Journal of Communication 13(2019), 1368–1388 1932–8036/20190005 Car Decals, Civic Rituals, and Changing Conceptions of Nationalism JOCELYN SAGE MITCHELL1 ILHEM ALLAGUI Northwestern University in Qatar With the onset of the Gulf diplomatic crisis in June 2017, citizens and expatriate residents in Qatar affixed patriotic decals to their cars in a show of support. Using visual evidence and ethnographic interviews gathered between August 2017 and September 2018, we analyze Qatari and expatriate participation in this shared ritual of nationalism, and what each group’s participation meant to the other. Our conclusions highlight the growth of civic nationalism narratives in Qatar as a response to the diplomatic crisis, and a corresponding reduction in regional ethnic narratives of communal belonging. Keywords: diplomatic crisis, nationalism, citizens, expatriates, Qatar What can a car decal tell us about changing conceptions of nationalism and belonging in Qatar? The small, resource-rich monarchy of Qatar is characterized as an “ethnocracy” (Longva, 2005), in which belonging to the nation is based on ethnicity. Regimes such as Qatar have citizenship laws that make it nearly impossible for foreigners to naturalize. Yet while legal citizenship remains inaccessible for most foreigners in these states, nationalism—both personal identification with and public practice of—may be an important part of these noncitizens’ daily lives and of the regimes’ political legitimacy. Nationalism in Qatar took on new importance on June 5, 2017, when regional neighbors Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Bahrain, along with Egypt, broke diplomatic relations with Qatar and closed their land, sea, and air borders. -

World Leaders in Oman to Mourn Sultan's Death

International MONDAY, JANUARY 13, 2020 Morrison proposes high-powered inquiry Malta gets new premier after outrage over blogger’s murder Page 8 into bushfires response Page 9 MUSCAT: A handout picture released by the Omani News Agency shows Oman’s newly sworn-in Sultan Haitham bin Tariq receiving Bahraini King Hamad bin Isa Al-Khalifa in the capital Muscat yesterday. Tariq received world leaders and officials who presented their condolences after the death of Sultan Qaboos of Oman, on January 10, at the age of 79. —AFP Photos World leaders in Oman to mourn Sultan’s death Ceremony at Alam Palace draws figures from across political divides in Mideast MUSCAT: Britain’s Prince Charles and of 79 without an heir apparent. goes back over 200 years,” it said. assuming power on Saturday to Prime Minister Boris Johnson joined It was Sultan Qaboos’ policy of “Our countries have deep economic uphold the foreign policy of his regional leaders in Oman yesterday to neutrality and non-interference that ties and shared defence and securi- Western-backed predecessor under offer their condolences to the royal elevated Oman’s standing as a ty interests.” which Muscat balanced ties family after the death of long-reigning “Switzerland of the Middle East” As ruler, Qaboos modernized his between larger neighbors Saudi Sultan Qaboos. A ceremony at and won it respect in the region and country but also forged a broader Arabia and Iran as well as the Muscat’s Alam Palace drew figures beyond. It maintains healthy rela- role as a go-between in regional United States. -

Middle East Flashpoint Centre for Mediterranean, Middle East & Islamic Studies University of Peloponnese

Middle East Flashpoint Centre for Mediterranean, Middle East & Islamic Studies University of Peloponnese www.cemmis.edu.gr No 114 17 February 2020 The new Sultan: Oman’s Regional and Domestic challenges Charitini Petrodaskalaki * Despite speculations of a rocky transition of power, Sultan Haitham bin Tariq Al Said’s succession at the Omani throne was swift and according to the wishes of the late Sultan. While he declared that he will follow the principles set by Qaboos in terms of foreign policy, the new ruler will have to prove Oman’s commitment to neutrality and its position as intermediary in negotiations, at a time of great regional turmoil. Meanwhile, Oman has to tackle its economic and social challenges at home, in order to continue to project its international soft power. *Researcher of the Centre for Mediterranean, Middle East and Islamic Studies of the University of Peloponnese Centre for Mediterranean, Middle East & Islamic Studies www.cemmis.edu.gr The year 2020 brought about multifaceted developments in the Middle East; from the assassination of the top Iranian general Qassem Suleimani by the United States, to the US-proposed peace plan for the resolution of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, to another significant change in Oman: Sultan Qaboos bin Said al- Said, the longest-ruling Arab monarch in modern history, passed away on January 10 at the age of 79. He rose to power in 1970, when, with help from Britain and the Shah of Iran, he deposed his father and suppressed an internal uprising. Soon he set out a program of rapid development and modernization, exploiting the country’s oil reserves, but also put an end to Oman’s international isolation. -

Draft Provisonal Agenda and Time-Table

IT/GB-5/13/Inf. 2 June 2013 FIFTH SESSION OF THE GOVERNING BODY Muscat, Oman, 24-28 September 2013 NOTE FOR PARTICIPANTS Last Update: 15 July 2013 1. MEETING ARRANGEMENTS .......................................................................................................... 2 DATE AND PLACE OF THE MEETING ........................................................................................................... 2 COMMUNICATIONS WITH THE SECRETARIAT ........................................................................................... 2 INVITATION LETTERS ................................................................................................................................. 2 ADMISSION OF PARTICIPANTS .................................................................................................................... 2 States that are Contracting Parties ......................................................................................................... 2 States that are not Contracting Parties................................................................................................... 3 Other international bodies or agencies .................................................................................................. 3 2. REGISTRATION ................................................................................................................................. 3 ONLINE PRE-REGISTRATION ..................................................................................................................... -

Oman Succession Crisis 2020

Oman Succession Crisis 2020 Invited Perspective Series Strategic Multilayer Assessment’s (SMA) Strategic Implications of Population Dynamics in the Central Region Effort This essay was written before the death of Sultan Qaboos on 20 January 2020. MARCH 18 STRATEGIC MULTILAYER ASSESSMENT Author: Vern Liebl, CAOCL, MCU Series Editor: Mariah Yager, NSI Inc. This paper represents the views and opinions of the contributing1 authors. This paper does not represent official USG policy or position. Vern Liebl Center for Advanced Operational Culture Learning, Marine Corps University Vern Liebl is an analyst currently sitting as the Middle East Desk Officer in the Center for Advanced Operational Culture Learning (CAOCL). Mr. Liebl has been with CAOCL since 2011, spending most of his time preparing Marines and sailors to deploy to Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and other interesting locales. Prior to joining CAOCL, Mr. Liebl worked with the Joint Improvised Explosives Device Defeat Organization as a Cultural SME and, before that, with Booz Allen Hamilton as a Strategic Islamic Narrative Analyst. Mr. Liebl retired from the Marine Corps, but while serving, he had combat tours to Afghanistan, Iraq, and Yemen, as well as numerous other deployments to many of the countries of the Middle East and Horn of Africa. He has an extensive background in intelligence, specifically focused on the Middle East and South Asia. Mr. Liebl has a Bachelor’s degree in political science from University of Oregon, a Master’s degree in Islamic History from the University of Utah, and a second Master’s degree in National Security and Strategic Studies from the Naval War College (where he graduated with “Highest Distinction” and focused on Islamic Economics). -

Who Is Who in Pakistan & Who Is Who in the World Study Material

1 Who is Who in Pakistan Lists of Government Officials (former & current) Governor Generals of Pakistan: Sr. # Name Assumed Office Left Office 1 Muhammad Ali Jinnah 15 August 1947 11 September 1948 (died in office) 2 Sir Khawaja Nazimuddin September 1948 October 1951 3 Sir Ghulam Muhammad October 1951 August 1955 4 Iskander Mirza August 1955 (Acting) March 1956 October 1955 (full-time) First Cabinet of Pakistan: Pakistan came into being on August 14, 1947. Its first Governor General was Muhammad Ali Jinnah and First Prime Minister was Liaqat Ali Khan. Following is the list of the first cabinet of Pakistan. Sr. Name of Minister Ministry 1. Liaqat Ali Khan Prime Minister, Foreign Minister, Defence Minister, Minister for Commonwealth relations 2. Malik Ghulam Muhammad Finance Minister 3. Ibrahim Ismail Chundrigar Minister of trade , Industries & Construction 4. *Raja Ghuzanfar Ali Minister for Food, Agriculture, and Health 5. Sardar Abdul Rab Nishtar Transport, Communication Minister 6. Fazal-ul-Rehman Minister Interior, Education, and Information 7. Jogendra Nath Mandal Minister for Law & Labour *Raja Ghuzanfar’s portfolio was changed to Minister of Evacuee and Refugee Rehabilitation and the ministry for food and agriculture was given to Abdul Satar Pirzada • The first Chief Minister of Punjab was Nawab Iftikhar. • The first Chief Minister of NWFP was Abdul Qayum Khan. • The First Chief Minister of Sindh was Muhamad Ayub Khuro. • The First Chief Minister of Balochistan was Ataullah Mengal (1 May 1972), Balochistan acquired the status of the province in 1970. List of Former Prime Ministers of Pakistan 1. Liaquat Ali Khan (1896 – 1951) In Office: 14 August 1947 – 16 October 1951 2. -

Nationalism in the Gulf States

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by LSE Research Online Kuwait Programme on Development, Governance and Globalisation in the Gulf States Nationalism in the Gulf States Neil Partrick October 2009 Number 5 The Kuwait Programme on Development, Governance and Globalisation in the Gulf States is a ten year multidisciplinary global programme. It focuses on topics such as globalisation, economic development, diversification of and challenges facing resource rich economies, trade relations between the Gulf States and major trading partners, energy trading, security and migration. The Programme primarily studies the six states that comprise the Gulf Cooperation Council – Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. However, it also adopts a more flexible and broader conception when the interests of research require that key regional and international actors, such as Yemen, Iraq, Iran, as well as its interconnections with Russia, China and India, be considered. The Programme is hosted in LSE’s interdisciplinary Centre for the Study of Global Governance, and led by Professor David Held, co- director of the Centre. It supports post-doctoral researchers and PhD students, develops academic networks between LSE and Gulf institutions, and hosts a regular Gulf seminar series at the LSE, as well as major biennial conferences in Kuwait and London. The Programme is funded by the Kuwait Foundation for the Advancement of Sciences. www.lse.ac.uk/LSEKP/ Nationalism in the Gulf States Research Paper, Kuwait Programme on Development, Governance and Globalisation in the Gulf States Dr Neil Partrick American University of Sharjah United Arab Emirates [email protected] Copyright © Neil Partrick 2009 The right of Neil Partrick to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

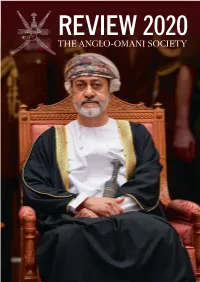

THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY REVIEW 2020 Project Associates’ Business Is to Build, Manage and Protect Our Clients’ Reputations

REVIEW 2020 THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY REVIEW 2020 Project Associates’ business is to build, manage and protect our clients’ reputations. Founded over 20 years ago, we advise corporations, individuals and governments on complex communication issues - issues which are usually at the nexus of the political, business, and media worlds. Our reach, and our experience, is global. We often work on complex issues where traditional models have failed. Whether advising corporates, individuals, or governments, our goal is to achieve maximum targeted impact for our clients. In the midst of a media or political crisis, or when seeking to build a profile to better dominate a new market or subject-area, our role is to devise communication strategies that meet these goals. We leverage our experience in politics, diplomacy and media to provide our clients with insightful counsel, delivering effective results. We are purposefully discerning about the projects we work on, and only pursue those where we can have a real impact. Through our global footprint, with offices in Europe’s major capitals, and in the United States, we are here to help you target the opinions which need to be better informed, and design strategies so as to bring about powerful change. Corporate Practice Private Client Practice Government & Political Project Associates’ Corporate Practice Project Associates’ Private Client Project Associates’ Government helps companies build and enhance Practice provides profile building & Political Practice provides strategic their reputations, in order to ensure and issues and crisis management advisory and public diplomacy their continued licence to operate. for individuals and families.