Oman Succession Crisis 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oman: Politics, Security, and U.S

Oman: Politics, Security, and U.S. Policy Updated January 27, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RS21534 SUMMARY RS21534 Oman: Politics, Security, and U.S. Policy January 27, 2020 The Sultanate of Oman has been a strategic partner of the United States since 1980, when it became the first Persian Gulf state to sign a formal accord permitting the U.S. military to use its Kenneth Katzman facilities. Oman has hosted U.S. forces during every U.S. military operation in the region since Specialist in Middle then, and it is a partner in U.S. efforts to counter terrorist groups and related regional threats. The Eastern Affairs January 2020 death of Oman’s longtime leader, Sultan Qaboos bin Sa’id Al Said, is unlikely to alter U.S.-Oman ties or Oman’s regional policies. His successor, Haythim bin Tariq Al Said, a cousin selected by Oman’s royal family immediately upon the Sultan’s death, espouses policies similar to those of Qaboos. During Qaboos’ reign (1970-2020), Oman generally avoided joining other countries in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC: Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, UAE, Bahrain, Qatar, and Oman) in regional military interventions, instead seeking to mediate their resolution. Oman joined the U.S.-led coalition against the Islamic State organization, but it did not send forces to that effort, nor did it support groups fighting Syrian President Bashar Al Asad’s regime. It opposed the June 2017 Saudi/UAE-led isolation of Qatar and did not join a Saudi-led regional counterterrorism alliance until a year after that group was formed in December 2015. -

GM ..L«»U2=U UM-H33 Casu

ROYAL NORWEGIAN EMBASSY 5*-.-94.3435‘5*-.=S1-5* U-I’--J‘ RIYADH-DQ — tLIUL§.unJ‘ UA 41441/05/24 zt-.0‘-'4‘ 92020/01/19:¢3éuA\ 2020/05/OM :5-3; MSL gmqfms,.asgmnUuamxwbuugíxgxgggàzgågíaeæymzesmwjiuméàg .2\,\_>,,,n\a_,_>,m\sfij,kgu..u^afè,fll\flej.fl\uu,gzsée,sfl\æsygmaxm dJ3---“ J93:-“ 43499oe gs:-*9 oe ~3-39/313--51‘ am 93! L§":‘JJ“‘as---S=u‘ 4-'9‘IMM” :0‘-A3"*3-‘=1-«e"‘-s+J‘$3* 0334'-“ 0° J-J3-“JW" .4:-I-w«JV-‘ea-U-C>eu-u-.I\3 oU=1--“3-D‘-ritési-.=5oJ=J‘J aw?‘ 1a,.;u\Q,é4:JuS!3Lu\,‘J\L§..ei¢51:,¢.,s:s1,s‘sM,.shi,‘9s‘Li‘s ¢§‘J'u:u\,.i.{§.;a:i ,9,.‘t...:.Js...a..':..x\,~\...,s..xsQ,:.L....\,..L§..s-.\\,.x§s:¢\;.s.;...,4.$:.1,34.,.;....x1g,:.s\ JLa.§s\,,:.\:J\4..\,':J\1:y..:.\J,;i:J4§3_i..,:;._,L.,.s;i..,c5L,.,,13¢,LLL..s\3\J>\.,¢,1s;§J 13s=;.ss‘,,A2x.sL.4..Js,?>L.4s_3,g.3s " L5-‘.-.UJ*-“deaéu‘ 4-'9‘/Saw-5‘ 43-2993;-'4‘ 3-.9354‘beis æugàmnUuaumgmgflaâumsuâaèæymaessánbmxJeg; ..L«»u2=uUM-H33 GM casu- :gun du; an.. 3,13.» s» J4‘-—-U5‘ Posta! Address Office Address Telephone: E4MaI1 P O Box 94380 Drplomatic Quarter +966 11 488 7904 [email protected] Rcyadh 11693 Riyadh Fax www.norway.no/en/saudi-arabIa/ Saudi Arabia Saudi Arabua +966 11 483 3168 ROYAL NORWEGIAN EMBASSY Ix,.+4,,,3s\3.,sJ..3ssJ1.i...J\ RIYADH-DQ üULÃuJl gå - Date: 19/01/2020 Ref: OM/05/2020 The Royal Norwegian Embassy presents its compliments to the Embassy of Sultanate of Oman in Riyadh and has the honor to convey, the following condolences message from H.E the Norwegian Minster of Foreign Affairs Ms. -

January 9, 1975 the President's Office 2:40 P.M

File scanned from the National Security Adviser's Memoranda of Conversation Collection at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON S13 SitE'£'I XGDS MEMORANDUM OF CONVERSATION PARTICIPANTS: His Majesty Qaboos bin Said, Sultan of Oman Qays Abd al-Munim Zawawi. Minister of State fo r Fo reign Affair Sayyid Tarik, Royal Advisor President Gerald R. Ford Dr. Henry A. Kissinger, Secretary of State and Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs Lt. General Brent Scowcroft DATE AND TIME: Thur sday, January 9. 1975 2:30 p. m. (45 minutes) PLACE: The Oval Office The President: We are very pleased to have you here. And we are very proud of our long relationship, which was established in 1833. ~ During Andrew Jackson's presidency. I wonder how someone from the ~ hills of Kentucky could be so farsighted. ~ 0;() J I understand we have the Peace Crops in your country. What do they do? ''; e;i Sultan Qaboos: I think they are out in the field mostly. !~!:oreign Minister: They are working mostly in agriculture. ~he President: We are revising the Peace Corps program. Now it Ilincludes a lot of retired people with real skills. Previously there were 21 .a lot of people who specialized in political matters. We have stopped most _.IO! that. .~ "." " • I wa.uld appreciate your views on South Yemen and the insurgency it'S!!~ 1~ supporting. ~ I Sultan Qaboos: They have been supporting revolutionaries and terrorists. - ;:..,..../ Jt They have two schools where they train about 500 young people whom they II Ii will later infiltrate not only into Oman but elsewhere. -

Amir Mourns H M Sultan Qaboos

www.thepeninsula.qa Volume 24 | Number 8134 SUNDAY 12 JANUARY 2020 17 JUMADA I - 1441 2 RIYALS BUSINESS | 17 SPORT | 24 ARTIC expands Rublev wins operational Qatar hotel portfolio ExxonMobil in Qatar Open Enjoy unlimited local data and calls with the new Qatarna 5G plans Amir, Putin hold phone talks, Amir mourns H M Sultan Qaboos discuss regional Qatar announces ‘Oman to continue path developments three days of QNA — DOHA mourning This is a sad day for all the Gulf people, as for the laid by Sultan Qaboos’ brothers in Oman. With great sorrow, we received in Amir H H Sheikh Tamim bin Qatar the news of the departure of Sultan Qaboos to the QNA — MUSCAT set by the late H M Sultan Hamad Al Thani held a tele- QNA — DOHA mercy of Allah The Almighty, leaving behind a rising Qaboos in bolstering cooper- phone conversation yesterday country and a great legacy that everyone cherishes. It is H M Sultan Haitham bin ation with brothers in the GCC with H E President Vladimir Amir H H Sheikh Tamim bin a great loss for the Arab and Islamic nations. We offer Tariq bin Taimur Al Said was and the Arab world without Putin of the friendly Russian Hamad Al Thani mourned condolences to the brotherly Omani people and we pray announced as the new Sultan interfering in the affairs of Federation. yesterday the death of H M to Allah for His Majesty the Supreme Paradise. of Oman, in succession to the others. Peace and coexistence During the phone call, they Sultan Qaboos bin Said bin late H M Sultan Qaboos bin will remain as cornerstones of discussed a number of regional Taimur of the Sultanate of and international issues of Oman, who passed away on common concern, especially Friday evening. -

Protest and State–Society Relations in the Middle East and North Africa

SIPRI Policy Paper PROTEST AND STATE– 56 SOCIETY RELATIONS IN October 2020 THE MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA dylan o’driscoll, amal bourhrous, meray maddah and shivan fazil STOCKHOLM INTERNATIONAL PEACE RESEARCH INSTITUTE SIPRI is an independent international institute dedicated to research into conflict, armaments, arms control and disarmament. Established in 1966, SIPRI provides data, analysis and recommendations, based on open sources, to policymakers, researchers, media and the interested public. The Governing Board is not responsible for the views expressed in the publications of the Institute. GOVERNING BOARD Ambassador Jan Eliasson, Chair (Sweden) Dr Vladimir Baranovsky (Russia) Espen Barth Eide (Norway) Jean-Marie Guéhenno (France) Dr Radha Kumar (India) Ambassador Ramtane Lamamra (Algeria) Dr Patricia Lewis (Ireland/United Kingdom) Dr Jessica Tuchman Mathews (United States) DIRECTOR Dan Smith (United Kingdom) Signalistgatan 9 SE-169 72 Solna, Sweden Telephone: + 46 8 655 9700 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.sipri.org Protest and State– Society Relations in the Middle East and North Africa SIPRI Policy Paper No. 56 dylan o’driscoll, amal bourhrous, meray maddah and shivan fazil October 2020 © SIPRI 2020 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of SIPRI or as expressly permitted by law. Contents Preface v Acknowledgements vi Summary vii Abbreviations ix 1. Introduction 1 Figure 1.1. Classification of countries in the Middle East and North Africa by 2 protest intensity 2. State–society relations in the Middle East and North Africa 5 Mass protests 5 Sporadic protests 16 Scarce protests 31 Highly suppressed protests 37 Figure 2.1. -

DOS: Foreign Relations of the United States: 1977-1980

FOREIGN RELATIONS OF THE UNITED STATES 1977–1980 VOLUME XVIII MIDDLE EAST REGION; ARABIAN PENINSULA DEPARTMENT OF STATE Washington 383-247/428-S/40005 6/18/2015 Foreign Relations of the United States, 1977–1980 Volume XVIII Middle East Region; Arabian Peninsula Editor Kelly M. McFarland General Editor Adam M. Howard United States Government Printing Office Washington 2015 383-247/428-S/40005 6/18/2015 DEPARTMENT OF STATE Office of the Historian Bureau of Public Affairs For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2250 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402-0001 383-247/428-S/40005 6/18/2015 About the Series The Foreign Relations of the United States series presents the official documentary historical record of major foreign policy decisions and significant diplomatic activity of the U.S. Government. The Historian of the Department of State is charged with the responsibility for the prep- aration of the Foreign Relations series. The staff of the Office of the Histo- rian, Bureau of Public Affairs, under the direction of the General Editor of the Foreign Relations series, plans, researches, compiles, and edits the volumes in the series. Secretary of State Frank B. Kellogg first promul- gated official regulations codifying specific standards for the selection and editing of documents for the series on March 26, 1925. These regu- lations, with minor modifications, guided the series through 1991. Public Law 102–138, the Foreign Relations Authorization Act, es- tablished a new statutory charter for the preparation of the series which was signed by President George H.W. -

World Leaders in Oman to Mourn Sultan's Death

International MONDAY, JANUARY 13, 2020 Morrison proposes high-powered inquiry Malta gets new premier after outrage over blogger’s murder Page 8 into bushfires response Page 9 MUSCAT: A handout picture released by the Omani News Agency shows Oman’s newly sworn-in Sultan Haitham bin Tariq receiving Bahraini King Hamad bin Isa Al-Khalifa in the capital Muscat yesterday. Tariq received world leaders and officials who presented their condolences after the death of Sultan Qaboos of Oman, on January 10, at the age of 79. —AFP Photos World leaders in Oman to mourn Sultan’s death Ceremony at Alam Palace draws figures from across political divides in Mideast MUSCAT: Britain’s Prince Charles and of 79 without an heir apparent. goes back over 200 years,” it said. assuming power on Saturday to Prime Minister Boris Johnson joined It was Sultan Qaboos’ policy of “Our countries have deep economic uphold the foreign policy of his regional leaders in Oman yesterday to neutrality and non-interference that ties and shared defence and securi- Western-backed predecessor under offer their condolences to the royal elevated Oman’s standing as a ty interests.” which Muscat balanced ties family after the death of long-reigning “Switzerland of the Middle East” As ruler, Qaboos modernized his between larger neighbors Saudi Sultan Qaboos. A ceremony at and won it respect in the region and country but also forged a broader Arabia and Iran as well as the Muscat’s Alam Palace drew figures beyond. It maintains healthy rela- role as a go-between in regional United States. -

Migration, Identity, and the Spatiality of Social Interaction In

MIGRATION, IDENTITY, AND THE SPATIALITY OF SOCIAL INTERACTION IN MUSCAT, SULTANATE OF OMAN by NICOLE KESSELL A THESIS Presented to the Department of International Studies and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts September 2017 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Nicole Kessell Title: Migration, Identity, and the Spatiality of Social Interaction in Muscat, Sultanate of Oman This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of International Studies by: Dennis C. Galvan Chairperson Alexander B. Murphy Member Yvonne Braun Member and Sara D. Hodges Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2017 ii © 2017 Nicole Kessell iii THESIS ABSTRACT Nicole Kessell Master of Arts Department of International Studies September 2017 Title: Migration, Identity, and the Spatiality of Social Interaction in Muscat, Sultanate of Oman Utilizing Henri Lefebvre’s theory of the production of space as a framework for exploration, this research is concerned with the social and cultural impacts of modernization and international migration to Muscat, Oman focusing on the production of space and its role in the modification and (re)construction of culture and identity in the everyday. While the Omani state is promoting a unifying national identity, Muscat residents are reconstructing and renegotiating culture and identity in the capital city. Individuals are adapting and conforming to, mediating, and contesting both the state’s identity project as well as to the equally, if not more, influential social control that is the culture of gossip and reputation. -

Middle East Flashpoint Centre for Mediterranean, Middle East & Islamic Studies University of Peloponnese

Middle East Flashpoint Centre for Mediterranean, Middle East & Islamic Studies University of Peloponnese www.cemmis.edu.gr No 114 17 February 2020 The new Sultan: Oman’s Regional and Domestic challenges Charitini Petrodaskalaki * Despite speculations of a rocky transition of power, Sultan Haitham bin Tariq Al Said’s succession at the Omani throne was swift and according to the wishes of the late Sultan. While he declared that he will follow the principles set by Qaboos in terms of foreign policy, the new ruler will have to prove Oman’s commitment to neutrality and its position as intermediary in negotiations, at a time of great regional turmoil. Meanwhile, Oman has to tackle its economic and social challenges at home, in order to continue to project its international soft power. *Researcher of the Centre for Mediterranean, Middle East and Islamic Studies of the University of Peloponnese Centre for Mediterranean, Middle East & Islamic Studies www.cemmis.edu.gr The year 2020 brought about multifaceted developments in the Middle East; from the assassination of the top Iranian general Qassem Suleimani by the United States, to the US-proposed peace plan for the resolution of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, to another significant change in Oman: Sultan Qaboos bin Said al- Said, the longest-ruling Arab monarch in modern history, passed away on January 10 at the age of 79. He rose to power in 1970, when, with help from Britain and the Shah of Iran, he deposed his father and suppressed an internal uprising. Soon he set out a program of rapid development and modernization, exploiting the country’s oil reserves, but also put an end to Oman’s international isolation. -

Who Is Who in Pakistan & Who Is Who in the World Study Material

1 Who is Who in Pakistan Lists of Government Officials (former & current) Governor Generals of Pakistan: Sr. # Name Assumed Office Left Office 1 Muhammad Ali Jinnah 15 August 1947 11 September 1948 (died in office) 2 Sir Khawaja Nazimuddin September 1948 October 1951 3 Sir Ghulam Muhammad October 1951 August 1955 4 Iskander Mirza August 1955 (Acting) March 1956 October 1955 (full-time) First Cabinet of Pakistan: Pakistan came into being on August 14, 1947. Its first Governor General was Muhammad Ali Jinnah and First Prime Minister was Liaqat Ali Khan. Following is the list of the first cabinet of Pakistan. Sr. Name of Minister Ministry 1. Liaqat Ali Khan Prime Minister, Foreign Minister, Defence Minister, Minister for Commonwealth relations 2. Malik Ghulam Muhammad Finance Minister 3. Ibrahim Ismail Chundrigar Minister of trade , Industries & Construction 4. *Raja Ghuzanfar Ali Minister for Food, Agriculture, and Health 5. Sardar Abdul Rab Nishtar Transport, Communication Minister 6. Fazal-ul-Rehman Minister Interior, Education, and Information 7. Jogendra Nath Mandal Minister for Law & Labour *Raja Ghuzanfar’s portfolio was changed to Minister of Evacuee and Refugee Rehabilitation and the ministry for food and agriculture was given to Abdul Satar Pirzada • The first Chief Minister of Punjab was Nawab Iftikhar. • The first Chief Minister of NWFP was Abdul Qayum Khan. • The First Chief Minister of Sindh was Muhamad Ayub Khuro. • The First Chief Minister of Balochistan was Ataullah Mengal (1 May 1972), Balochistan acquired the status of the province in 1970. List of Former Prime Ministers of Pakistan 1. Liaquat Ali Khan (1896 – 1951) In Office: 14 August 1947 – 16 October 1951 2. -

THE PREVALENCE of GUILE: Deception Through Time and Across Cultures and Disciplines

2 February 2007 THE PREVALENCE OF GUILE: Deception through Time and across Cultures and Disciplines by Barton Whaley “The Game is so large that one sees but a little at a time.” —Kipling, Kim (1901), Chapter 10 Foreign Denial & Deception Committee National Intelligence Council Office of the Director of National Intelligence Washington, DC 2007 -ii- CONTENTS Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................... iv INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 1. In a Nutshell: What I Expected & What I Found 2. Force versus Guile 3. The Importance of Guile in War, Politics, and Philosophy PART ONE: OF TIME, CULTURES, & DISCIPLINES ................................................. 11 4. Tribal Warfare 5. The Classical West 6. Decline in the Medieval West 7. The Byzantine Style 8. The Scythian Style 9. The Renaissance of Deception 10. Discontinuity: “Progress” and Romanticism in the 19th Century 11. The Chinese Way 12. The Japanese Style 13. India plus Pakistan 14. Arabian to Islamic Culture 15. Twentieth Century Limited 16. Soviet Doctrine 17. American Roller-coaster and the Missing Generation 18. Twenty-First Century Unlimited: Asymmetric Warfare Revisited PART TWO: LIMITATIONS ON THE PRACTICE OF DECEPTION ............................ 58 19. Biological Limitations: Nature & Nurture 20. Cultural Limitations: Philosophies, Religions, & Languages 21. Social Limitations: Ethical Codes and Political -

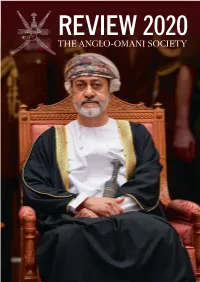

THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY REVIEW 2020 Project Associates’ Business Is to Build, Manage and Protect Our Clients’ Reputations

REVIEW 2020 THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY REVIEW 2020 Project Associates’ business is to build, manage and protect our clients’ reputations. Founded over 20 years ago, we advise corporations, individuals and governments on complex communication issues - issues which are usually at the nexus of the political, business, and media worlds. Our reach, and our experience, is global. We often work on complex issues where traditional models have failed. Whether advising corporates, individuals, or governments, our goal is to achieve maximum targeted impact for our clients. In the midst of a media or political crisis, or when seeking to build a profile to better dominate a new market or subject-area, our role is to devise communication strategies that meet these goals. We leverage our experience in politics, diplomacy and media to provide our clients with insightful counsel, delivering effective results. We are purposefully discerning about the projects we work on, and only pursue those where we can have a real impact. Through our global footprint, with offices in Europe’s major capitals, and in the United States, we are here to help you target the opinions which need to be better informed, and design strategies so as to bring about powerful change. Corporate Practice Private Client Practice Government & Political Project Associates’ Corporate Practice Project Associates’ Private Client Project Associates’ Government helps companies build and enhance Practice provides profile building & Political Practice provides strategic their reputations, in order to ensure and issues and crisis management advisory and public diplomacy their continued licence to operate. for individuals and families.