The Language Planning Situation in the Sultanate of Oman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Migration, Identity, and the Spatiality of Social Interaction In

MIGRATION, IDENTITY, AND THE SPATIALITY OF SOCIAL INTERACTION IN MUSCAT, SULTANATE OF OMAN by NICOLE KESSELL A THESIS Presented to the Department of International Studies and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts September 2017 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Nicole Kessell Title: Migration, Identity, and the Spatiality of Social Interaction in Muscat, Sultanate of Oman This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of International Studies by: Dennis C. Galvan Chairperson Alexander B. Murphy Member Yvonne Braun Member and Sara D. Hodges Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2017 ii © 2017 Nicole Kessell iii THESIS ABSTRACT Nicole Kessell Master of Arts Department of International Studies September 2017 Title: Migration, Identity, and the Spatiality of Social Interaction in Muscat, Sultanate of Oman Utilizing Henri Lefebvre’s theory of the production of space as a framework for exploration, this research is concerned with the social and cultural impacts of modernization and international migration to Muscat, Oman focusing on the production of space and its role in the modification and (re)construction of culture and identity in the everyday. While the Omani state is promoting a unifying national identity, Muscat residents are reconstructing and renegotiating culture and identity in the capital city. Individuals are adapting and conforming to, mediating, and contesting both the state’s identity project as well as to the equally, if not more, influential social control that is the culture of gossip and reputation. -

Draft Provisonal Agenda and Time-Table

IT/GB-5/13/Inf. 2 June 2013 FIFTH SESSION OF THE GOVERNING BODY Muscat, Oman, 24-28 September 2013 NOTE FOR PARTICIPANTS Last Update: 15 July 2013 1. MEETING ARRANGEMENTS .......................................................................................................... 2 DATE AND PLACE OF THE MEETING ........................................................................................................... 2 COMMUNICATIONS WITH THE SECRETARIAT ........................................................................................... 2 INVITATION LETTERS ................................................................................................................................. 2 ADMISSION OF PARTICIPANTS .................................................................................................................... 2 States that are Contracting Parties ......................................................................................................... 2 States that are not Contracting Parties................................................................................................... 3 Other international bodies or agencies .................................................................................................. 3 2. REGISTRATION ................................................................................................................................. 3 ONLINE PRE-REGISTRATION ..................................................................................................................... -

Unsettling State: Non-Citizens, State Power

UNSETTLING STATE: NON-CITIZENS, STATE POWER AND CITIZENSHIP IN THE UNITED ARAB EMIRATES by Noora Anwar Lori A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science Baltimore, Maryland October, 2013 ABSTRACT: This dissertation examines the development and enforcement of citizenship and immigration policies in the United Arab Emirates in order to revisit an enduring puzzle in comparative politics: why are resource-rich states resiliently authoritarian? The dominant explanation for the ‘oil curse’ assumes that authoritarianism emerges because regimes ‘purchase’ the political acquiescence of their citizens by redistributing rents. However, prior to the redistribution of rents comes the much more fundamental question of who will be included in the group of beneficiaries. I argue that oil facilitates the creation of authoritarian power structures because when political elites gain control over fixed assets, they can more effectively erect high barriers to political incorporation. By combining stringent citizenship policies with temporary worker programs, political elites develop their resources while concentrating the redistribution of assets to a very small percentage of the total population. In the UAE, this policy combination has been so effective that non-citizens now comprise 96 percent of the domestic labor force. The boundaries of the UAE’s citizenry became increasingly stringent as oil production was converted into revenue in the 1960s. Since oil reserves are unevenly distributed across the emirates, the political elites who signed concessions with successful oil prospectors have since monopolized control over the composition of the citizenry. As a result, domestic minorities who were previously incorporated by smaller emirates who did not discover oil have since been excluded from the citizenry. -

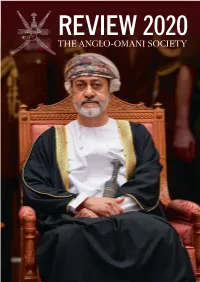

THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY REVIEW 2020 Project Associates’ Business Is to Build, Manage and Protect Our Clients’ Reputations

REVIEW 2020 THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY REVIEW 2020 Project Associates’ business is to build, manage and protect our clients’ reputations. Founded over 20 years ago, we advise corporations, individuals and governments on complex communication issues - issues which are usually at the nexus of the political, business, and media worlds. Our reach, and our experience, is global. We often work on complex issues where traditional models have failed. Whether advising corporates, individuals, or governments, our goal is to achieve maximum targeted impact for our clients. In the midst of a media or political crisis, or when seeking to build a profile to better dominate a new market or subject-area, our role is to devise communication strategies that meet these goals. We leverage our experience in politics, diplomacy and media to provide our clients with insightful counsel, delivering effective results. We are purposefully discerning about the projects we work on, and only pursue those where we can have a real impact. Through our global footprint, with offices in Europe’s major capitals, and in the United States, we are here to help you target the opinions which need to be better informed, and design strategies so as to bring about powerful change. Corporate Practice Private Client Practice Government & Political Project Associates’ Corporate Practice Project Associates’ Private Client Project Associates’ Government helps companies build and enhance Practice provides profile building & Political Practice provides strategic their reputations, in order to ensure and issues and crisis management advisory and public diplomacy their continued licence to operate. for individuals and families. -

Rifts in Omani Employment Culture: Emerging Joblessness in the Context of Uneven Development

Rifts in Omani Employment Culture: Emerging Joblessness in the Context of Uneven Development. The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Al-Hashmi, Julanda S. H. 2019. Rifts in Omani Employment Culture: Emerging Joblessness in the Context of Uneven Development.. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42004191 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Rifts in Omani Employment Culture: Emerging Joblessness in the Context of Uneven Development. A Julanda S. H. Al-Hashmi A Thesis in the Field of Government for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University March 2019 Copyright ! Julanda Al-Hashmi 2019 Abstract Beginning in 1970, Oman experienced modernization at a rapid pace due to the discovery of oil. At that time, the country still had not invested much in infrastructure development, and a large part of the national population had low levels of literacy as they lacked formal education. For these reasons, the national workforce was unable to fuel the growing oil and gas sector, and the Omani government found it necessary to import foreign labor during the 1970s. Over the ensuing decades, however, the reliance on foreign labor has remained and has led to sharp labor market imbalances. Today the foreign-born population is 45 percent of Oman’s total population and makes up an overwhelming 89 percent of the private sector workforce. -

Omani Undergraduate Students', Teachers' and Tutors' Metalinguistic

Omani Undergraduate Students’, Teachers’ and Tutors’ Metalinguistic Understanding of Cohesion and Coherence in EFL Academic Writing and their Perspectives of Teaching Cohesion and Coherence Al Siyabi, Jamila Abdullah Kharboosh Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education March 2019 1 Omani Undergraduate Students’, Teachers’ and Tutors’ Metalinguistic Understanding of Cohesion and Coherence in EFL Academic Writing and their Perspectives of Teaching Cohesion and Coherence Submitted by Jamila Abdullah Kharboosh Al Siyabi to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education, March 2019. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (Signed) Jamila 2 ABSTRACT My interpretive study aims to explore how EFL university students verbally articulate their understanding of cohesion and coherence, how they perceive the teaching of cohesion and coherence and how they reflect on the way they have attempted to actualise cohesion and coherence in their EFL academic texts. The study also looks at how their writing teachers and tutors metalinguistically understand cohesion and coherence, and how they perceive issues related to the teaching/tutoring of cohesion and coherence. It has researched the situated realities of students, teachers and tutors through semi-structured interviews, and is informed by Halliday and Hasan’s (1976) taxonomy on cohesion and coherence. -

2006 Presldenllalawardees Who Have Shown Lhe Best of the Fil,Plno

MALACANAN PALACE ",,",LA Time and again I have acknowledged the Invaluable contribuhOn ofour overseas Filipinos to national development and nation build Lng They have shared their skills and expertise to enable the Philippines to benefit from advances in sCience and technology RemiUing more than $70 billion in the last ten years, they have contributed Slgnlficanlly to our counlry's economic stability and social progress of our people. Overseas Filipinos have also shown that they are dependable partners, providl!'lQ additional resources to augment programs in health, educatIOn, livelihood projects and small infrastructure in the country, We pay tnbute to Filipinos overseas who have dedicated themselves to uplifting the human condiloOn, those who have advocated the cause of Filipinos worldwide, and who continue to bring pride and honor to lhe Philippines by their pursuit of excellence I ask the rest of the FilipinO nation to Join me in congratulating the 2006 PreSldenllalAwardees who have shown lhe best of the Fil,plno. I also extend my thanks to the men and women of the CommiSSion on Filipinos Overseas and the vanous Awards commillees for a job well done in thiS biennial search. Mabuhay kayong lahalr Mantia. 7 Decemoor 2006 , Office of Itle Pres,dent of !he Ph''PP'nes COMMISSION ON FILIPINOS OVERSEAS Today, some 185 million men, women and even children, represent,rog about 3 percent of the world's population, live Ofwork outside their country of origin. No reg,on in the world is WIthout migrants who live or work within its borders Every country is now an origin ordeslination for international migration. -

Paper Submitted by H.E. Malallah Bin Ali Bin Habib Al-Lawati at The

Sultanate of Oman Ministry of National Heritage & Culture Paper submitted by H.E. Malallah bin Ali bin Habib Al-Lawati at the International Seminar of "the Contributions of the Islamic Culture for the Maritime Silk Route" Quanzhou, China, 21-26 February, 1994 International Expedition of "the Islamic Culture along the Coast of China" 27 February - 16 March, 1994 1 Sultanate of Oman Ministry of National Heritage & Culture OMAN AN ENTRÉPOT ON THE MARITIME TRADE ROUTES The Irish explorer Tim Severin in his book 'THE SINDBAD VOYAGE' claims that Omanis have known seafaring ever since man knew the mast and sail. But the recorded history of their negotiation with sea, however, begins in the 3rd millennium BC when Sumerians had settled in northern Oman and mined Copper in Sohar which they called Magan. They sent this copper to the town of Urr in Mesopotamia where they had their headquarters. Apparently the copper was transported by Omani ships. King Sargon of Akkad is said to have praised the Omani ships anchored in an Iraqi Port bringing copper and diorite stones from Magan. The early contact of the Omani People with the sea could be attributed to the following factors:- a) Its location at crossroads between South East Asia, the Middle East and Africa. b) Its long shores extending from Hurmuz Straits on the extreme north down to Yemen - Oman borders. c) Its safe and convenient natural sea-havens for ships. The ports of Muscat, Sohar and Qalhat provided safe shelters plus abundant supplies to ships in all seasons. By virtue of seafaring, Omanis were excellent ship-builders. -

THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY REVIEW 2019 W&S Anglo-Omani-2019-Issue.Indd 1

REVIEW 2019 THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY REVIEW 2019 WWW.WILLIAMANDSON.COM THE PERFECT DESTINATION FOR TOWN & COUNTRY LIVING W&S_Anglo-Omani-2019-Issue.indd 1 19/08/2019 11:51 COVER PHOTO: REVIEW 2019 Jokha Alharthi, winner of the Man Booker International Prize WWW.WILLIAMANDSON.COM THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY CONTENTS 6 CHAIRMAN’S OVERVIEW 62 CHINA’S BELT AND ROAD INITIATIVE 9 NEW WEBSITE FOR THE SOCIETY 64 OMAN AND THE MIDDLE EAST INFRASTRUCTURE BOOM 10 JOKHA ALHARTHI AWARDED THE MAN BOOKER INTERNATIONAL PRIZE 66 THE GULF RESEARCH MEETING AT CAMBRIDGE 13 OLLIE BLAKE’S WEDDING IN CANADA 68 OMAN AND ITS NEIGHBOURS 14 HIGH-LEVEL PARLIAMENTARY EXCHANGES 69 5G NATIONAL WORKING GROUP VISIT TO UK 16 INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON OMANI- 70 OBBC AND OMAN’S VISION 2040 BRITISH RELATIONS IN THE 19TH CENTURY 72 GHAZEER – KHAZZAN PHASE 2 18 ARAB WOMEN AWARD FOR OMANI FORMER MINISTER 74 OLD MUSCAT 20 JOHN CARBIS – OMAN EXPERIENCE 76 OMANI BRITISH LAWYERS ASSOCIATION ANNUAL LONDON RECEPTION 23 THE WORLD’S OLDEST MARINER’S ASTROLABE 77 LONDON ORGAN RECITAL 26 OMAN’S NATURAL HERITAGE LECTURE 2018 79 OUTWARD BOUND OMAN 30 BATS, RODENTS AND SHREWS OF DHOFAR 82 ANGLO-OMANI LUNCHEON 2018 84 WOMEN’S VOICES – THE SOCIETY’S PROGRAMME FOR NEXT YEAR 86 ARABIC LANGUAGE SCHEME 90 GAP YEAR SCHEME REPORT 93 THE SOCIETY’S GRANT SCHEME 94 YOUNG OMANI TEACHERS VISIT BRITISH SCHOOLS 34 ISLANDS IN THE DESERT 96 UNLOCKING THE POTENTIAL OF OMAN’S YOUTH 40 THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF EARLY ISLAM IN OMAN 98 NGG DELEGATION – THE NUDGE FACTOR 44 MILITANT JIHADIST POETRY -

Participant List

Participant List 10/20/2019 8:45:44 AM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jillian Abballe UN Advocacy Officer and Anglican Communion United States Head of Office Ramil Abbasov Chariman of the Managing Spektr Socio-Economic Azerbaijan Board Researches and Development Public Union Babak Abbaszadeh President and Chief Toronto Centre for Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership in Financial Supervision Amr Abdallah Director, Gulf Programs Educaiton for Employment - United States EFE HAGAR ABDELRAHM African affairs & SDGs Unit Maat for Peace, Development Egypt AN Manager and Human Rights Abukar Abdi CEO Juba Foundation Kenya Nabil Abdo MENA Senior Policy Oxfam International Lebanon Advisor Mala Abdulaziz Executive director Swift Relief Foundation Nigeria Maryati Abdullah Director/National Publish What You Pay Indonesia Coordinator Indonesia Yussuf Abdullahi Regional Team Lead Pact Kenya Abdulahi Abdulraheem Executive Director Initiative for Sound Education Nigeria Relationship & Health Muttaqa Abdulra'uf Research Fellow International Trade Union Nigeria Confederation (ITUC) Kehinde Abdulsalam Interfaith Minister Strength in Diversity Nigeria Development Centre, Nigeria Kassim Abdulsalam Zonal Coordinator/Field Strength in Diversity Nigeria Executive Development Centre, Nigeria and Farmers Advocacy and Support Initiative in Nig Shahlo Abdunabizoda Director Jahon Tajikistan Shontaye Abegaz Executive Director International Insitute for Human United States Security Subhashini Abeysinghe Research Director Verite -

Residential Schools, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylania Press, 2004

Table of Contents I.Introduction 3 II. Historical Overview of Boarding Schools 2 A. What was their purpose? 2 B. In what countries were they located 3 United States 3 Central/South America and Caribbean 10 Australia 12 New Zealand 15 Scandinavia 18 Russian Federation 20 Asia 21 Africa 25 Middle East 24 C. What were the experiences of indigenous children? 28 D. What were the major successes and failures? 29 E. What are their legacies today and what can be learned from them? 30 III. The current situation/practices/ideologies of Boarding Schools 31 A. What purpose do they currently serve for indigenous students (eg for nomadic communities, isolated and remote communities) and/or the solution to address the low achievements rates among indigenous students? 31 North America 31 Australia 34 Asia 35 Latin America 39 Russian Federation 40 Scandinavia 41 East Africa 42 New Zealand 43 IV. Assessment of current situation/practices/ideologies of Boarding Schools 43 A. Highlight opportunities 43 B. Highlight areas for concern 45 C. Highlight good practices 46 V. Conclusion 48 VI. Annotated Bibliography 49 I. Introduction At its sixth session, the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues recommended that an expert undertake a comparative study on the subject of boarding schools.1 This report provides a preliminary analysis of boarding school policies directed at indigenous peoples globally. Because of the diversity of indigenous peoples and the nation-states in which they are situated, it is impossible to address all the myriad boarding school policies both historically and contemporary. Boarding schools have had varying impacts for indigenous peoples. -

15714 Yenigun 2021 E1.Docx

International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change. www.ijicc.net Volume 15, Issue 7, 2021 The Omani Diaspora in Eastern Africa Cuneyt Yeniguna, Yasir AlRahbib, aAssociate Professor, Director of International Relations and Security Studies Graduate Programs, Founder of Political Science Department, College of Economics and Political Science, Sultan Qaboos University, Muscat, Oman, bOman National Defence College, Sultan Qaboos University, IRSS Graduate Program, M.A. in International Relations, Muscat, Oman. Email: [email protected], [email protected]; [email protected], [email protected] Diasporas play an important role in international relations by connecting homeland and host country. Diasporas can act as a bridge between the sending states and the receiving states in promoting peace and security, and in facilitating economic cooperation between the two sides. Omani people started to settle into Eastern Africa 1300 years ago. It intensified dramatically and reached its peak during the Golden Age of Oman. After Oman lost power and territories in the last century, the natural Omani Diaspora emerged in five different African countries. Perhaps there are millions of Omanis in the region, but the data is not well known. This study concentrates historical background of the Omani Diaspora and today’s Omani Diaspora situation in the region. To understand their current situation in the region, a visit plan was projected and 4 countries and 17 cities were visited, 155 families’ representatives were interviewed with 13 interview questions. In this study, the Omani Diaspora’s tendencies, cultural developments, family relations, home country (Oman) relations, economic situation, political participation, and civil organisational capabilities have been explored.