Evaluating the Resonance of Official Islam in Oman, Jordan, and Morocco

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Letter to His Holiness Pope Benedict Xvi

In the Name of God, the Compassionate , the Merciful, And may Peace and Blessings be upon the Prophet Muhammad OPEN LETTER TO HIS HOLINESS POPE BENEDICT XVI In the Name of God, the Compassionate , the Merciful, Do not contend with people of the Book except in the fairest way …. (The Holy Qur’an, al-Ankabut , : ). Your Holiness, September th , we thought it appropriate, in the spirit of open exchange, to address your use of a debate between the Emperor Manuel II Paleologus and a “learned Persian” as the starting point for a discourse on the relationship between reason and faith. While we applaud your efforts to oppose the dominance of positivism and materialism in human life, we must point out some errors in the way you mentioned Islam as a counterpoint to the proper use of reason, as well as some mistakes in the assertions you put forward in support of your argument. There is no Compulsion in Religion You mention that “according to the experts ” the verse which begins, There is no compulsion in religion (al-Baqarah : ) is from the early period when the Prophet “was still powerless and under threat,” but this is incorrect. In fact this verse is acknowledged to belong to the period of Quranic revelation corresponding to the political and military ascendance of the young Muslim community. There is no compulsion in religion was not a command to Muslims to remain steadfast in the face of the desire of their oppressors to force them to renounce their faith, but was a reminder to Muslims themselves, once they had attained power, that they could not force another’s heart to believe. -

A Mainstream Islamic Response to the Beliefs and Practices of Islamic State

DIOCESAN SYNOD - 15.11.14 A Mainstream Islamic response to the beliefs and prac5ces of Islamic State Imam Monawar Hussain Muslim Tutor, Eton College Founder, The Oxford Foundaon www.theoxfordfoundaon.com Aims • What is Mainstream Islam? • What is extremist theology? Al-Qaeda, Al— Shabab, IS, ISIL, 9/11,7/7, Pakistani/Afghani Taliban share the same theology. We can only defeat these groups if we can defeat the theology that underpins them. • Mainstream responses Qur’an Hadith Primary Sources of Islam ©Imam Monawar Hussain Linguisc Sufi / Understanding Tradi5onalist Esoteric the Qur’an Tradi5onalist & Raonalist ©Imam Monawar Hussain Islam Hadith of Jibril Iman Ihsan ©Imam Monawar Hussain Shahada Hajj Salah Islam Zakah Sawm ©Imam Monawar Hussain Belief in Allah Desny, both the His Angels good and evil Iman Day of His Revealed Judgement Books His Messengers ©Imam Monawar Hussain Doing that Perfecon which is of Faith beau5ful Ihsan ©Imam Monawar Hussain Historical unfolding of the dimension ‘Islam’ Usul al-Fiqh / Principles of Jurisprudence Fiqh (Understanding) / Orthopraxis Sunni Schools of Law /Shi’i Schools of Law ©Imam Monawar Hussain Theology Ilm al-Kalam Iman School of al-Ashari (d. 324 AH / 936 CE) School of al-Maturidi (d. 333 AH / 944 CE) Khawarij (late 7th century) ©Imam Monawar Hussain Sufism Numerous Spiritual Orders Ihsan Naqshbandi Qadari Chish Shadhali Mevlevi ©Imam Monawar Hussain Extremist Theology • Interprets the Qur‘ān literally. • They are selec5ve in the hadīth they use. • Arbitrarily declare Muslims non-Muslim (Tak*r) and therefore jus5fy killing civilians. • Jus5fy rebellion against central Authority. • A Theology of Separateness - Separate themselves from the community of Muslims. -

United Arab Emirates (Uae)

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: United Arab Emirates, July 2007 COUNTRY PROFILE: UNITED ARAB EMIRATES (UAE) July 2007 COUNTRY اﻟﻌﺮﺑﻴّﺔ اﻟﻤﺘّﺤﺪة (Formal Name: United Arab Emirates (Al Imarat al Arabiyah al Muttahidah Dubai , أﺑﻮ ﻇﺒﻲ (The seven emirates, in order of size, are: Abu Dhabi (Abu Zaby .اﻹﻣﺎرات Al ,ﻋﺠﻤﺎن Ajman , أ مّ اﻟﻘﻴﻮﻳﻦ Umm al Qaywayn , اﻟﺸﺎرﻗﺔ (Sharjah (Ash Shariqah ,دﺑﻲّ (Dubayy) .رأس اﻟﺨﻴﻤﺔ and Ras al Khaymah ,اﻟﻔﺠﻴﺮة Fajayrah Short Form: UAE. اﻣﺮاﺗﻰ .(Term for Citizen(s): Emirati(s أﺑﻮ ﻇﺒﻲ .Capital: Abu Dhabi City Major Cities: Al Ayn, capital of the Eastern Region, and Madinat Zayid, capital of the Western Region, are located in Abu Dhabi Emirate, the largest and most populous emirate. Dubai City is located in Dubai Emirate, the second largest emirate. Sharjah City and Khawr Fakkan are the major cities of the third largest emirate—Sharjah. Independence: The United Kingdom announced in 1968 and reaffirmed in 1971 that it would end its treaty relationships with the seven Trucial Coast states, which had been under British protection since 1892. Following the termination of all existing treaties with Britain, on December 2, 1971, six of the seven sheikhdoms formed the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The seventh sheikhdom, Ras al Khaymah, joined the UAE in 1972. Public holidays: Public holidays other than New Year’s Day and UAE National Day are dependent on the Islamic calendar and vary from year to year. For 2007, the holidays are: New Year’s Day (January 1); Muharram, Islamic New Year (January 20); Mouloud, Birth of Muhammad (March 31); Accession of the Ruler of Abu Dhabi—observed only in Abu Dhabi (August 6); Leilat al Meiraj, Ascension of Muhammad (August 10); first day of Ramadan (September 13); Eid al Fitr, end of Ramadan (October 13); UAE National Day (December 2); Eid al Adha, Feast of the Sacrifice (December 20); and Christmas Day (December 25). -

Sunni – Shi`A Relations and the Implications for Belgium and Europe

FEARING A ‘SHIITE OCTOPUS’ SUNNI – SHI`A RELATIONS AND THE IMPLICATIONS FOR BELGIUM AND EUROPE EGMONT PAPER 35 FEARING A ‘SHIITE OCTOPUS’ Sunni – Shi`a relations and the implications for Belgium and Europe JELLE PUELINGS January 2010 The Egmont Papers are published by Academia Press for Egmont – The Royal Institute for International Relations. Founded in 1947 by eminent Belgian political leaders, Egmont is an independent think-tank based in Brussels. Its interdisciplinary research is conducted in a spirit of total academic freedom. A platform of quality information, a forum for debate and analysis, a melting pot of ideas in the field of international politics, Egmont’s ambition – through its publications, seminars and recommendations – is to make a useful contribution to the decision- making process. *** President: Viscount Etienne DAVIGNON Director-General: Marc TRENTESEAU Series Editor: Prof. Dr. Sven BISCOP *** Egmont - The Royal Institute for International Relations Address Naamsestraat / Rue de Namur 69, 1000 Brussels, Belgium Phone 00-32-(0)2.223.41.14 Fax 00-32-(0)2.223.41.16 E-mail [email protected] Website: www.egmontinstitute.be © Academia Press Eekhout 2 9000 Gent Tel. 09/233 80 88 Fax 09/233 14 09 [email protected] www.academiapress.be J. Story-Scientia NV Wetenschappelijke Boekhandel Sint-Kwintensberg 87 B-9000 Gent Tel. 09/225 57 57 Fax 09/233 14 09 [email protected] www.story.be All authors write in a personal capacity. Lay-out: proxess.be ISBN 978 90 382 1538 9 D/2010/4804/17 U 1384 NUR1 754 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the publishers. -

Israeli–Palestinian Peacemaking January 2019 Middle East and North the Role of the Arab States Africa Programme

Briefing Israeli–Palestinian Peacemaking January 2019 Middle East and North The Role of the Arab States Africa Programme Yossi Mekelberg Summary and Greg Shapland • The positions of several Arab states towards Israel have evolved greatly in the past 50 years. Four of these states in particular – Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the UAE and (to a lesser extent) Jordan – could be influential in shaping the course of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. • In addition to Egypt and Jordan (which have signed peace treaties with Israel), Saudi Arabia and the UAE, among other Gulf states, now have extensive – albeit discreet – dealings with Israel. • This evolution has created a new situation in the region, with these Arab states now having considerable potential influence over the Israelis and Palestinians. It also has implications for US positions and policy. So far, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the UAE and Jordan have chosen not to test what this influence could achieve. • One reason for the inactivity to date may be disenchantment with the Palestinians and their cause, including the inability of Palestinian leaders to unite to promote it. However, ignoring Palestinian concerns will not bring about a resolution of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, which will continue to add to instability in the region. If Arab leaders see regional stability as being in their countries’ interests, they should be trying to shape any eventual peace plan advanced by the administration of US President Donald Trump in such a way that it forms a framework for negotiations that both Israeli and Palestinian leaderships can accept. Israeli–Palestinian Peacemaking: The Role of the Arab States Introduction This briefing forms part of the Chatham House project, ‘Israel–Palestine: Beyond the Stalemate’. -

Oman: Politics, Security, and U.S

Oman: Politics, Security, and U.S. Policy Updated May 19, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RS21534 SUMMARY RS21534 Oman: Politics, Security, and U.S. Policy May 19, 2021 The Sultanate of Oman has been a strategic partner of the United States since 1980, when it became the first Persian Gulf state to sign a formal accord permitting the U.S. military to use its Kenneth Katzman facilities. Oman has hosted U.S. forces during every U.S. military operation in the region since Specialist in Middle then, and it is a partner in U.S. efforts to counter terrorist groups and other regional threats. In Eastern Affairs January 2020, Oman’s longtime leader, Sultan Qaboos bin Sa’id Al Said, passed away and was succeeded by Haythim bin Tariq Al Said, a cousin selected by Oman’s royal family immediately upon Qaboos’s death. Sultan Haythim espouses policies similar to those of Qaboos and has not altered U.S.-Oman ties or Oman’s regional policies. During Qaboos’s reign (1970-2020), Oman generally avoided joining other countries in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC: Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, United Arab Emirates , Bahrain, Qatar, and Oman) in regional military interventions, instead seeking to mediate their resolution. Oman joined but did not contribute forces to the U.S.-led coalition against the Islamic State organization, nor did it arm groups fighting Syrian President Bashar Al Asad’s regime. It opposed the June 2017 Saudi/UAE- led isolation of Qatar and had urged resolution of that rift before its resolution in January 2021. -

The Islamist Movement in Morocco. Main Actors and Regime Responses

DIIS REPORT 2010:05 DIIS REPORT THE ISLAMIST MOVEMENT IN MOROCCO MAIN ACTORS AND REGIME RESPONSES Julie E. Pruzan-Jørgensen DIIS REPORT 2010:05 DIIS REPORT DIIS . DANISH INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES 1 DIIS REPORT 2010:05 © Copenhagen 2010 Danish Institute for International Studies, DIIS Strandgade 56, DK-1401 Copenhagen, Denmark Ph: +45 32 69 87 87 Fax: +45 32 69 87 00 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.diis.dk Cover Design: Anine Kristensen Cover Photo: Polfoto.dk Layout: Allan Lind Jørgensen Printed in Denmark by Vesterkopi AS ISBN 978-87-7605-378-9 Price: DKK 50.00 (VAT included) DIIS publications can be downloaded free of charge from www.diis.dk Hardcopies can be ordered at www.diis.dk The report was commissioned by the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, but its findings and conclusions are entirely the responsibility of the author. Julie E. Pruzan-Jørgensen, Project Researcher, Religion, Conflict and International Politics, DIIS 2 DIIS REPORT 2010:05 Contents Abstract 4 Introduction 5 Religion and Politics in Morocco 6 The Islamist Movement in Morocco 8 Developments within MUR/PJD 11 Developments within Justice and Spirituality 15 Regime Responses: Reforms and Repression 19 Future Scenarios 24 Literature 26 3 DIIS REPORT 2010:05 Abstract Morocco’s formally accepted Islamist party, the Justice and Development Party (PJD), has further underlined its recognition of the authoritarian regime in response to a disappointing electoral showing and tough competition from the new Authenticity and Modernity Party (PAM). In contrast, the forbidden, although tolerated, Justice and Spirituality Movement (Al Adl wal Ihsan) retains its principled oppositional role. -

Draft Provisonal Agenda and Time-Table

IT/GB-5/13/Inf. 2 June 2013 FIFTH SESSION OF THE GOVERNING BODY Muscat, Oman, 24-28 September 2013 NOTE FOR PARTICIPANTS Last Update: 15 July 2013 1. MEETING ARRANGEMENTS .......................................................................................................... 2 DATE AND PLACE OF THE MEETING ........................................................................................................... 2 COMMUNICATIONS WITH THE SECRETARIAT ........................................................................................... 2 INVITATION LETTERS ................................................................................................................................. 2 ADMISSION OF PARTICIPANTS .................................................................................................................... 2 States that are Contracting Parties ......................................................................................................... 2 States that are not Contracting Parties................................................................................................... 3 Other international bodies or agencies .................................................................................................. 3 2. REGISTRATION ................................................................................................................................. 3 ONLINE PRE-REGISTRATION ..................................................................................................................... -

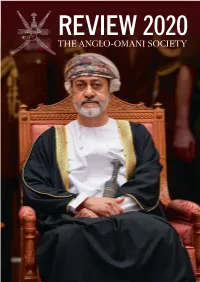

THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY REVIEW 2020 Project Associates’ Business Is to Build, Manage and Protect Our Clients’ Reputations

REVIEW 2020 THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY REVIEW 2020 Project Associates’ business is to build, manage and protect our clients’ reputations. Founded over 20 years ago, we advise corporations, individuals and governments on complex communication issues - issues which are usually at the nexus of the political, business, and media worlds. Our reach, and our experience, is global. We often work on complex issues where traditional models have failed. Whether advising corporates, individuals, or governments, our goal is to achieve maximum targeted impact for our clients. In the midst of a media or political crisis, or when seeking to build a profile to better dominate a new market or subject-area, our role is to devise communication strategies that meet these goals. We leverage our experience in politics, diplomacy and media to provide our clients with insightful counsel, delivering effective results. We are purposefully discerning about the projects we work on, and only pursue those where we can have a real impact. Through our global footprint, with offices in Europe’s major capitals, and in the United States, we are here to help you target the opinions which need to be better informed, and design strategies so as to bring about powerful change. Corporate Practice Private Client Practice Government & Political Project Associates’ Corporate Practice Project Associates’ Private Client Project Associates’ Government helps companies build and enhance Practice provides profile building & Political Practice provides strategic their reputations, in order to ensure and issues and crisis management advisory and public diplomacy their continued licence to operate. for individuals and families. -

Rifts in Omani Employment Culture: Emerging Joblessness in the Context of Uneven Development

Rifts in Omani Employment Culture: Emerging Joblessness in the Context of Uneven Development. The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Al-Hashmi, Julanda S. H. 2019. Rifts in Omani Employment Culture: Emerging Joblessness in the Context of Uneven Development.. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42004191 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Rifts in Omani Employment Culture: Emerging Joblessness in the Context of Uneven Development. A Julanda S. H. Al-Hashmi A Thesis in the Field of Government for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University March 2019 Copyright ! Julanda Al-Hashmi 2019 Abstract Beginning in 1970, Oman experienced modernization at a rapid pace due to the discovery of oil. At that time, the country still had not invested much in infrastructure development, and a large part of the national population had low levels of literacy as they lacked formal education. For these reasons, the national workforce was unable to fuel the growing oil and gas sector, and the Omani government found it necessary to import foreign labor during the 1970s. Over the ensuing decades, however, the reliance on foreign labor has remained and has led to sharp labor market imbalances. Today the foreign-born population is 45 percent of Oman’s total population and makes up an overwhelming 89 percent of the private sector workforce. -

A Study of Ibadi Oman

UCLA Journal of Religion Volume 2 2018 Developing Tolerance and Conservatism: A Study of Ibadi Oman Connor D. Elliott The George Washington University ABSTRACT This thesis analyzes the development of Omani-Ibadi society from pre- Islam to the present day. Oman represents an anomaly in the religious world because its Ibadi theology is conservative in nature while also preaching unwavering tolerance. To properly understand how Oman developed such a unique culture and religion, it is necessary to historically analyze the country by recounting the societal developments that occurred throughout the millennia. By doing so, one begins to understand that Oman did not achieve this peaceful religious theology over the past couple of decades. Oman has an exceptional society that was built out of longtime traditions like a trade-based economy that required foreign interaction, long periods of political sovereignty or autonomy, and a unique theology. The Omani-Ibadi people and their leaders have continuously embraced the ancient roots of their regional and religious traditions to create a contemporary state that espouses a unique society that leads people to live conservative personal lives while exuding outward tolerance. Keywords: Oman, Ibadi, Tolerance, Theology, History, Sociology UCLA Journal of Religion Vol. 2, 2018 Developing Tolerance and Conservatism: A Study of Ibadi Oman By Connor D. Elliott1 The George Washington University INTRODUCTION he Sultanate of Oman is a country which consistently draws acclaim T for its tolerance and openness towards peoples of varying faiths. The sect of Islam most Omanis follow, Ibadiyya, is almost entirely unique to Oman with over 2 million of the 2.5 million Ibadis worldwide found in the sultanate.2 This has led many to see the Omani government as the de facto state-representative of Ibadiyya in contemporary times. -

Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination Alternative Report Submission Indigenous Rights Violations in Algeria

Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination Alternative Report Submission Indigenous Rights Violations in Algeria Prepared for: The 94th Session of the Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination Submission Date: November 2017 Submitted by: Cultural Survival 2067 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02140 Tel: 1 (617) 441 5400 [email protected] www.culturalsurvival.org I. Reporting Organization Cultural Survival is an international Indigenous rights organization with a global Indigenous leadership and consultative status with ECOSOC since 2005. Cultural Survival is located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and is registered as a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization in the United States. Cultural Survival monitors the protection of Indigenous Peoples' rights in countries throughout the world and publishes its findings in its magazine, the Cultural Survival Quarterly, and on its website: www.cs.org. Cultural Survival also produces and distributes quality radio programs that strengthen and sustain Indigenous languages, cultures, and civil participation. II. Background Information: History, Population and Regions The total population of Algeria is estimated to be just over 41 million.1 The majority of the population — about 90% — are the Arab people living in the northern coastal regions.2 In addition, Algeria also has a nomadic or semi-nomadic population of about 1.5 million.3 Generally, the Indigenous People of Algeria are called Berbers; however, the term is regarded as a pejorative, as it comes from the word “barbarian.”4 As a result, although not officially recognized as Indigenous,5 Algeria's Indigenous Peoples self-identity as the Imazighen (plural) or Amazigh (singular).6 Due to lack of recognition, there is no official statistics or disaggregated data available on Algeria’s Indigenous population.