2020 State Rail Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Usair Rejected Contracts.Pdf

US Airways Exhibit 1 Contract Company Entity Contact Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 City State Zip Country Contract No. Effective Date Product Description The following executory contracts were not assumed under the First Amended Joint Plan of Reorganization and, pursuant to Section 8.2 of the Plan and Paragraph 18 of the Confirmation Order, are rejected effective on the earlier of (a) the date such Rejected Agreement expires or is terminated in accordance with the terms of such agreement or (b) January 5, 2004. This action was taken as a result of the growing instability in the airline industry and the unknown impact of the Iraqi war. Prior to the effective rejection date, the applicable company entity will fully perform its obligations under the executory contracts to the extent required by applicable law and will seek to negotiate new agreements to reduce operating costs and utilize facilities to best suit its business plan and operational needs or make other arrangements. LANDSIDE Pittsburgh, PA ALLEGHENY COUNTY AIRPORT DIRECTOR OF TERMINAL - SUITE Pittsburgh Hangar 3/4 #7977 AUTHORITY Mainline AVIATION 4000 PO BOX 12370 International Airport PITTSBURGH PA 15231 PIT 0463L00100 10/1/63 MAINTENANCE LEASE MAINTENANCE Lease LANDSIDE Pittsburgh, PA ALLEGHENY COUNTY AIRPORT DIRECTOR OF TERMINAL - SUITE Pittsburgh SSB #7977-B AUTHORITY Mainline AVIATION 4000 PO BOX 12370 International Airport Piitsburgh PA 15231 PIT 0473L00100 1/1/73 MAINTENANCE LEASE MAINTENANCE Lease National Transportation Center 534 Union Trust Bldg. Pittsburgh, PA National -

GAO-02-398 Intercity Passenger Rail: Amtrak Needs to Improve Its

United States General Accounting Office Report to the Honorable Ron Wyden GAO U.S. Senate April 2002 INTERCITY PASSENGER RAIL Amtrak Needs to Improve Its Decisionmaking Process for Its Route and Service Proposals GAO-02-398 Contents Letter 1 Results in Brief 2 Background 3 Status of the Growth Strategy 6 Amtrak Overestimated Expected Mail and Express Revenue 7 Amtrak Encountered Substantial Difficulties in Expanding Service Over Freight Railroad Tracks 9 Conclusions 13 Recommendation for Executive Action 13 Agency Comments and Our Evaluation 13 Scope and Methodology 16 Appendix I Financial Performance of Amtrak’s Routes, Fiscal Year 2001 18 Appendix II Amtrak Route Actions, January 1995 Through December 2001 20 Appendix III Planned Route and Service Actions Included in the Network Growth Strategy 22 Appendix IV Amtrak’s Process for Evaluating Route and Service Proposals 23 Amtrak’s Consideration of Operating Revenue and Direct Costs 23 Consideration of Capital Costs and Other Financial Issues 24 Appendix V Market-Based Network Analysis Models Used to Estimate Ridership, Revenues, and Costs 26 Models Used to Estimate Ridership and Revenue 26 Models Used to Estimate Costs 27 Page i GAO-02-398 Amtrak’s Route and Service Decisionmaking Appendix VI Comments from the National Railroad Passenger Corporation 28 GAO’s Evaluation 37 Tables Table 1: Status of Network Growth Strategy Route and Service Actions, as of December 31, 2001 7 Table 2: Operating Profit (Loss), Operating Ratio, and Profit (Loss) per Passenger of Each Amtrak Route, Fiscal Year 2001, Ranked by Profit (Loss) 18 Table 3: Planned Network Growth Strategy Route and Service Actions 22 Figure Figure 1: Amtrak’s Route System, as of December 2001 4 Page ii GAO-02-398 Amtrak’s Route and Service Decisionmaking United States General Accounting Office Washington, DC 20548 April 12, 2002 The Honorable Ron Wyden United States Senate Dear Senator Wyden: The National Railroad Passenger Corporation (Amtrak) is the nation’s intercity passenger rail operator. -

PIT VP Public Safety

The Airports & ACAA Allegheny County Airport Authority (ACAA) oversees and maintains Pittsburgh International Airport and Allegheny County Airport. Pittsburgh International Airport Pittsburgh International Airport (PIT) is in Findlay and Moon townships in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, about 20 miles west of downtown Pittsburgh. It is the second-busiest airport in Pennsylvania, after Philadelphia International Airport, serving nearly 9 million passengers in 2017. To manage growing passenger traffic, construction began on the original Greater Pittsburgh International Airport in 1946 and opened in 1952. Over time, as passenger traffic further increased, services were expanded both domestically and internationally. Allegheny County and ACAA undertook a major, nearly billion-dollar airport expansion in 1987. The new Pittsburgh International Airport opened in 1992 and has been ranked highly by travelers and industry journals. In January 2018, Air Transport World magazine named PIT its 2017 Airport of the Year, placing the airport in prestigious company alongside past winners Hong Kong International, London Heathrow and Singapore Changi. (continued...) page 2 The Airports & ACAA (continued) J.D. Power ranked Pittsburgh International in its Top 10 medium-size airports in its 2015 North American Airport Satisfaction Study. Travel + Leisure also named Pittsburgh International a Top 10 Domestic Airport in 2016. TripAdvisor ranked Pittsburgh International Airport a Traveler’s Choice Favorite for Shopping in 2016. Now, PIT is undergoing a Terminal Modernization Program which promises to positively change the air travel experience in and out of Pittsburgh for decades. In addition, by adding more nonstop flights, PIT has opened more of the nation and world to Pittsburgh for business and leisure travelers. -

RAILROAD COMMUNICATIONS Amtrak

RAILROAD COMMUNICATIONS Amtrak Amtrak Police Department (APD) Frequency Plan Freq Input Chan Use Tone 161.295 R (160.365) A Amtrak Police Dispatch 71.9 161.295 R (160.365) B Amtrak Police Dispatch 100.0 161.295 R (160.365) C Amtrak Police Dispatch 114.8 161.295 R (160.365) D Amtrak Police Dispatch 131.8 161.295 R (160.365) E Amtrak Police Dispatch 156.7 161.295 R (160.365) F Amtrak Police Dispatch 94.8 161.295 R (160.365) G Amtrak Police Dispatch 192.8 161.295 R (160.365) H Amtrak Police Dispatch 107.2 161.205 (simplex) Amtrak Police Car-to-Car Primary 146.2 160.815 (simplex) Amtrak Police Car-to-Car Secondary 146.2 160.830 R (160.215) Amtrak Police CID 123.0 173.375 Amtrak Police On-Train Use 203.5 Amtrak Police Area Repeater Locations Chan Location A Wilmington, DE B Morrisville, PA C Philadelphia, PA D Gap, PA E Paoli, PA H Race Amtrak Police 10-Codes 10-0 Emergency Broadcast 10-21 Call By Telephone 10-1 Receiving Poorly 10-22 Disregard 10-2 Receiving Well 10-24 Alarm 10-3 Priority Service 10-26 Prepare to Copy 10-4 Affirmative 10-33 Does Not Conform to Regulation 10-5 Repeat Message 10-36 Time Check 10-6 Busy 10-41 Begin Tour of Duty 10-7 Out Of Service 10-45 Accident 10-8 Back In Service 10-47 Train Protection 10-10 Vehicle/Person Check 10-48 Vandalism 10-11 Request Additional APD Units 10-49 Passenger/Patron Assist 10-12 Request Supervisor 10-50 Disorderly 10-13 Request Local Jurisdiction Police 10-77 Estimated Time of Arrival 10-14 Request Ambulance or Rescue Squad 10-82 Hostage 10-15 Request Fire Department 10-88 Bomb Threat 10-16 -

Rules and Regulations

Rules and Regulations Rules & Regulations | 02.12.21 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................4 ARTICLE I: DEFINITIONS ....................................................................................6 ARTICLE II: GENERAL CONDUCT .................................................................... 12 ARTICLE III: DOING BUSINESS AT THE AIRPORT .......................................... 16 ARTICLE IV: COMMUNICATION ........................................................................ 24 ARTICLE V: APRON OPERATIONS................................................................... 26 ARTICLE VI: MOTOR VEHICLES ....................................................................... 28 ARTICLE VII: FIRE AND SAFETY ...................................................................... 37 ARTICLE VIII: ACAA TENANT AND CONTRACTOR FIRE POLICY AND HAZARDOUS MATERIAL ................................................................................... 41 ARTICLE IX: SANITATION AND ENVIRONMENTAL ......................................... 46 ARTICLE X: SECURITY ...................................................................................... 49 ARTICLE XI: FUELING ....................................................................................... 55 ARTICLE XII: WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT ........................................................... 66 ARTICLE XIII: DEFINITIONS, NOTICE OF VIOLATIONS, ENFORCEMENT / PENALTIES ............................................................................... -

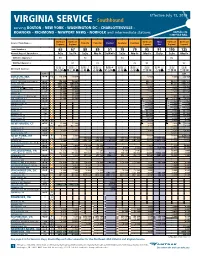

Amtrak Timetables-Virginia Service

Effective July 13, 2019 VIRGINIA SERVICE - Southbound serving BOSTON - NEW YORK - WASHINGTON DC - CHARLOTTESVILLE - ROANOKE - RICHMOND - NEWPORT NEWS - NORFOLK and intermediate stations Amtrak.com 1-800-USA-RAIL Northeast Northeast Northeast Silver Northeast Northeast Service/Train Name4 Palmetto Palmetto Cardinal Carolinian Carolinian Regional Regional Regional Star Regional Regional Train Number4 65 67 89 89 51 79 79 95 91 195 125 Normal Days of Operation4 FrSa Su-Th SaSu Mo-Fr SuWeFr SaSu Mo-Fr Mo-Fr Daily SaSu Mo-Fr Will Also Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 Will Not Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 9/2 R B y R B y R B y R B y R B s R B y R B y R B R s y R B R B On Board Service4 Q l å O Q l å O l å O l å O r l å O l å O l å O y Q å l å O y Q å y Q å Symbol 6 R95 BOSTON, MA ∑w- Dp l9 30P l9 30P 6 10A 6 30A 86 10A –South Station Boston, MA–Back Bay Station ∑v- R9 36P R9 36P R6 15A R6 35A 8R6 15A Route 128, MA ∑w- lR9 50P lR9 50P R6 25A R6 46A 8R6 25A Providence, RI ∑w- l10 22P l10 22P 6 50A 7 11A 86 50A Kingston, RI (b(™, i(¶) ∑w- 10 48P 10 48P 7 11A 7 32A 87 11A Westerly, RI >w- 11 05P 11 05P 7 25A 7 47A 87 25A Mystic, CT > 11 17P 11 17P New London, CT (Casino b) ∑v- 11 31P 11 31P 7 45A 8 08A 87 45A Old Saybrook, CT ∑w- 11 53P 11 53P 8 04A 8 27A 88 04A Springfield, MA ∑v- 7 05A 7 25A 7 05A Windsor Locks, CT > 7 24A 7 44A 7 24A Windsor, CT > 7 29A 7 49A 7 29A Train 495 Train 495 Hartford, CT ∑v- 7 39A Train 405 7 59A 7 39A Berlin, CT >v D7 49A 8 10A D7 49A Meriden, CT >v D7 58A 8 19A D7 58A Wallingford, CT > D8 06A 8 27A D8 06A State Street, CT > q 8 19A 8 40A 8 19A New Haven, CT ∑v- Ar q q 8 27A 8 47A 8 27A NEW HAVEN, CT ∑v- Ar 12 30A 12 30A 4 8 41A 4 9 03A 4 88 41A Dp l12 50A l12 50A 8 43A 9 05A 88 43A Bridgeport, CT >w- 9 29A Stamford, CT ∑w- 1 36A 1 36A 9 30A 9 59A 89 30A New Rochelle, NY >w- q 10 21A NEW YORK, NY ∑w- Ar 2 30A 2 30A 10 22A 10 51A 810 22A –Penn Station Dp l3 00A l3 25A l6 02A l5 51A l6 45A l7 17A l7 25A 10 35A l11 02A 11 05A 11 35A Newark, NJ ∑w- 3 20A 3 45A lR6 19A lR6 08A lR7 05A lR7 39A lR7 44A 10 53A lR11 22A 11 23A 11 52A Newark Liberty Intl. -

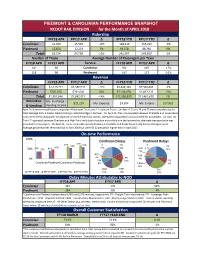

Piedmont and Carolinian Performance Snapshot

PIEDMONT & CAROLINIAN PERFORMANCE SNAPSHOT NCDOT RAIL DIVISION for the Month of APRIL 2018 Ridership FFY18 APR FFY17 APR Δ FFY18 YTD FFY17 YTD Δ Carolinian 21,060 25,525 -17% 148,219 155,219 -5% Piedmont 12,654 12,233 3% 93,378 88,284 6% Total 33,714 37,758 -11% 241,597 243,503 -1% Number of Trains Average Number of Passengers per Train FFY18 APR FFY17 APRService FFY18 APR FFY17 APR Δ 60 60 Carolinian 351 425 -17% 118 96 Piedmont 107 127 -16% Revenue FFY18 APR FFY17 APR Δ FFY18 YTD FFY17 YTD Δ Carolinian $1,310,771 $1,586,931 -17% $9,442,344 $9,564,446 -1% Piedmont $287,075 $261,040 10% $2,144,476 $1,897,232 13% Total $1,597,846 $1,847,971 -14% $11,586,820 $11,461,678 1% Amenities Mo. Surcharge + $21,214 Mo. Expense $3,304 Mo. Surplus $17,910 & Vending Vending Income April 2018 service modifications impacted 4 Piedmont Trains and 2 Carolinian Trains. On April 4, Trains 74 and 75 were cancelled due to track damage from a tractor trailer striking a railroad bridge in Durham. On April 15, Train 76 operated between Charlotte and Greensboro only due to trees and powerlines downed across the tracks by storms; alternate transportation was provided for passengers. On April 18, Train 74 operated between Charlotte and High Point only due to traction motor failure in the locomotive; alternate transportation was provided for passengers. On April 22, Trains 79 and 80 operated between Charlotte and Rocky Mount only due to CSX signal work. -

Pioneering the Application of High Speed Rail Express Trainsets in the United States

Parsons Brinckerhoff 2010 William Barclay Parsons Fellowship Monograph 26 Pioneering the Application of High Speed Rail Express Trainsets in the United States Fellow: Francis P. Banko Professional Associate Principal Project Manager Lead Investigator: Jackson H. Xue Rail Vehicle Engineer December 2012 136763_Cover.indd 1 3/22/13 7:38 AM 136763_Cover.indd 1 3/22/13 7:38 AM Parsons Brinckerhoff 2010 William Barclay Parsons Fellowship Monograph 26 Pioneering the Application of High Speed Rail Express Trainsets in the United States Fellow: Francis P. Banko Professional Associate Principal Project Manager Lead Investigator: Jackson H. Xue Rail Vehicle Engineer December 2012 First Printing 2013 Copyright © 2013, Parsons Brinckerhoff Group Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic, mechanical (including photocopying), recording, taping, or information or retrieval systems—without permission of the pub- lisher. Published by: Parsons Brinckerhoff Group Inc. One Penn Plaza New York, New York 10119 Graphics Database: V212 CONTENTS FOREWORD XV PREFACE XVII PART 1: INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION TO THE RESEARCH 3 1.1 Unprecedented Support for High Speed Rail in the U.S. ....................3 1.2 Pioneering the Application of High Speed Rail Express Trainsets in the U.S. .....4 1.3 Research Objectives . 6 1.4 William Barclay Parsons Fellowship Participants ...........................6 1.5 Host Manufacturers and Operators......................................7 1.6 A Snapshot in Time .................................................10 CHAPTER 2 HOST MANUFACTURERS AND OPERATORS, THEIR PRODUCTS AND SERVICES 11 2.1 Overview . 11 2.2 Introduction to Host HSR Manufacturers . 11 2.3 Introduction to Host HSR Operators and Regulatory Agencies . -

Pennsylvania's Welfare to Work Transportation Program

Pennsylvania’s Welfare to Work Transportation Program OUTCOME REPORT FY 2002 – 2003 “With reliable transportation services, welfare recipients will experience success in the workplace, without it they will struggle to reach the job that could bring them economic security.” Joblinks 1 PENNSYLVANIA’S WELFARE TO WORK (w2w) TRANSPORTATION PROGRAM OUTCOME REPORT: FY 2002 – 2003 SECTION PAGE 1. W2W PROGRAM OBJECTIVES 3 2. MAP WITH W2W FUNDED SERVICES 6 3. STATE AND FEDERAL 2002-2003 FUNDING 7 4. COMPARISON OF 01-02 AND 02-03 SPENDING 7 5. NUMBER AND TYPE OF CLIENTS SERVED 8 6. TYPES OF TRANSPORTATION SERVICES 9 7. COMPARISON OF SERVICES: 01-02 vs. 02-03 10 8. IMPACT OF W2W ON ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT 11 9. W2W STATISTICAL OUTCOMES 12 10. GRANTEE 2002-03 AND PRIOR AWARDS 13 11. GRANTEE FUNDING EXPENDED: 2002-2003 15 12. FUNDS EXPENDED 1997-2003 17 13. KEY W2W ACTIVITIES/ACTIONS: 20 - OUTCOME REPORT 2001-02 22 - ANNUAL GRANTEE MEETINGS 25 - JOBLINKS COORDINATION COMMITTEE 28 APPENDICES A – GRANTEE PROJECT REPORTS 30 B – STATE PARTNERS: DPW, L&I, AND DCED 63 2 WELFARE TO WORK TRANSPORTATION PROGRAM OUTCOME REPORT 02-03 When Pennsylvania initiated its Welfare Reform activities in 1997, transportation and child care were identified as the two major barriers to employment for low-income residents. In order to connect recipients of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and other low-income persons with jobs that are often located in suburban areas with minimal public transportation from urban and rural areas, appropriate and affordable transportation is essential. Therefore, the Departments of Public Welfare and Transportation (PENNDOT) established the welfare to work (w2w) Transportation Demonstration Program with these four Objectives: Formation of Partnerships - for cooperation and coordination between the transit provider and local organizations essential to the project. -

Geospatial Analysis: Commuters Access to Transportation Options

Advocacy Sustainability Partnerships Fort Washington Office Park Transportation Demand Management Plan Geospatial Analysis: Commuters Access to Transportation Options Prepared by GVF GVF July 2017 Contents Executive Summary and Key Findings ........................................................................................................... 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 6 Sources ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 ArcMap Geocoding and Data Analysis .................................................................................................. 6 Travel Times Analysis ............................................................................................................................ 7 Data Collection .......................................................................................................................................... 7 1. Employee Commuter Survey Results ................................................................................................ 7 2. Office Park Companies Outreach Results ......................................................................................... 7 3. Office Park -

CAPITOL LIMITED Train Time Schedule & Line Route

CAPITOL LIMITED train time schedule & line map Capitol Limited View In Website Mode The train line Capitol Limited has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Chicago Union Station: 4:05 PM (2) Washington Union Station: 7:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest CAPITOL LIMITED train station near you and ƒnd out when is the next CAPITOL LIMITED train arriving. Direction: Chicago Union Station CAPITOL LIMITED train Time Schedule 16 stops Chicago Union Station Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 4:05 PM Monday 4:05 PM Union Station 50 Massachusetts Avenue Ne, Washington Tuesday 4:05 PM Rockville Amtrak Wednesday 4:05 PM 250 Rockville Pike, Rockville Thursday 4:05 PM Harpers Ferry Amtrak Friday 4:05 PM 182 Potomac St, Harpers Ferry Saturday 4:05 PM Martinsburg Amtrak Station 229 East Martin Street, Berkeley County Cumberland Amtrak Station 200 Park St, Cumberland CAPITOL LIMITED train Info Direction: Chicago Union Station Connellsville Amtrak Stops: 16 Trip Duration: 1060 min Pittsburgh Amtrak Station Line Summary: Union Station, Rockville Amtrak, 1100 Liberty Avenue, Pittsburgh Harpers Ferry Amtrak, Martinsburg Amtrak Station, Cumberland Amtrak Station, Connellsville Amtrak, Alliance Amtrak Pittsburgh Amtrak Station, Alliance Amtrak, Cleveland, Elyria Amtrak, Sandusky Amtrak Station, Cleveland Toledo, Waterloo Amtrak Station, Elkhart Amtrak 200 Cleveland Memorial Shoreway, Cleveland Station, South Bend Amtrak Station, Chicago Union Station Elyria Amtrak 410 East River Road, Elyria Sandusky Amtrak Station -

Quarterly Report on the Performance and Service Quality of Intercity Passenger Train Operations

Pursuant to Section 207 of the Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act of 2008 (Public Law 110-432, Division B): Quarterly Report on the Performance and Service Quality of Intercity Passenger Train Operations Covering the Quarter Ended June, 2019 (Third Quarter of Fiscal Year 2019) Federal Railroad Administration United States Department of Transportation Published August 2019 Table of Contents (Notes follow on the next page.) Financial Table 1 (A/B): Short-Term Avoidable Operating Costs (Note 1) Table 2 (A/B): Fully Allocated Operating Cost covered by Passenger-Related Revenue Table 3 (A/B): Long-Term Avoidable Operating Loss (Note 1) Table 4 (A/B): Adjusted Loss per Passenger- Mile Table 5: Passenger-Miles per Train-Mile On-Time Performance (Table 6) Test No. 1 Change in Effective Speed Test No. 2 Endpoint OTP Test No. 3 All-Stations OTP Train Delays Train Delays - Off NEC Table 7: Off-NEC Host Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Table 8: Off-NEC Amtrak Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Train Delays - On NEC Table 9: On-NEC Total Host and Amtrak Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Other Service Quality Table 10: Customer Satisfaction Indicator (eCSI) Scores Table 11: Service Interruptions per 10,000 Train-Miles due to Equipment-related Problems Table 12: Complaints Received Table 13: Food-related Complaints Table 14: Personnel-related Complaints Table 15: Equipment-related Complaints Table 16: Station-related Complaints Public Benefits (Table 17) Connectivity Measure Availability of Other Modes Reference Materials Table 18: Route Descriptions Terminology & Definitions Table 19: Delay Code Definitions Table 20: Host Railroad Code Definitions Appendixes A.