The Post-Revolutionary Transformation of the Indonesian Army*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stud Y Guide

INTRODUCTION N SEPTEMBER 30TH, 1965, an unsuccessful Ocoup d’état triggered a series of events that have decided the course of Indonesia’s history to this very day. The leadership of President Sukarno, the man who led Indonesia to independence in NICK WILSON h 1949, was undermined, and the ascendancy of his successor, Suharto, was established. The orientation of this new nation, an amalgamation of peoples of dis- parate religions and languages living across a huge archipelago, was to change from fragile de- mocracy and neutral alignment (dependent upon balancing the GUIDE competing infl uences of Com- munism, Western colonialism, and a power-hungry army) to a military dictatorship aligned with the West. STUDY ISSUE 29 AUSTRALIAN SCREEN EDUCATION ABOVE: RICE FARMERS, CENTRAL JAVA 1 THE FAILED COUP TRIGGERED a or since, but now a full and frank ac- were part of a broader response to terror campaign, led by General Su- count of the slaughter of hundreds of events in South-East Asia. The Viet- harto. This culminated in the deposing thousands of people can be given. The nam War was escalating in 1965, and of Sukarno and the establishment of fi lm even explains some of the reasons the anti-Communist West decided Suharto’s New Order in 1966. At least for the West’s silence. that President Sukarno’s power de- fi ve hundred thousand people and pended upon Communist sup- perhaps as many as one million port. His removal from power and were killed during this period in replacement with an acceptable, purges organized by the military anti-Communist leader became a in conjunction with civilian militias. -

1 11103100105681 Irwadi Batubara, MM. Universitas Ibnu Chaldun M 2 11103100106543 Leonardus Subagyo, M.Sc

Hasil Laporan No. Nomor Sertifikat Nama Tempat Tugas Keterangan BKD BKD 1 11103100105681 Irwadi Batubara, MM. Universitas Ibnu Chaldun M 2 11103100106543 Leonardus Subagyo, M.Sc. Universitas Ibnu Chaldun M 3 11103100112471 Urhen Lukman, MA. Universitas Ibnu Chaldun M 4 08156103357 Ir. Mulki Siregar, MT. Universitas Islam Jakarta M 5 08156109369 Ir. Achmad Sutrisna, MT. Universitas Islam Jakarta M 6 08156110926 Muhammad Ali Yusuf, SE., M.Pd. Universitas Islam Jakarta M 7 08156110927 Farhana, SH., MH. Universitas Islam Jakarta M 8 091156100635 Edi Suhara, SE, MM. Universitas Islam Jakarta M 9 091156101331 Hamdan Azhar Siregar, SH, MH. Universitas Islam Jakarta M 10 091156102156 Ir. Untung Setiyo Purwanto, MT. Universitas Islam Jakarta M 11 091156105753 Endang Saefuddin Mubarok, SE, MM. Universitas Islam Jakarta M 12 101156100184 Siti Miskiah, SH., MH. Universitas Islam Jakarta M 13 101156100185 Mimin Mintarsih, SH,. MH. Universitas Islam Jakarta M 14 101156100186 Otom Mustomi, SH,. MH. Universitas Islam Jakarta M 15 11103100303161 Eka Sutisna, SE., MM. Universitas Islam Jakarta M 16 11103100306739 H. Lukman Achmad, SE., MM. Universitas Islam Jakarta M 17 11103100308546 Nur Aida, SH., M.Si. Universitas Islam Jakarta M 18 11103100309779 Ritawati, SH., MH. Universitas Islam Jakarta M 19 11103100315557 Bambang Sukamto, SH., MH. Universitas Islam Jakarta M 20 11103100316046 Fatimah, SH., MH. Universitas Islam Jakarta M 21 11103100318366 Yusri Ilyas, SE., MM. Universitas Islam Jakarta M 22 12103100313055 Untoro, SH., MH. Universitas Islam Jakarta M 23 08156211262 Tri Rumayanto, S.Si., M.Si. Universitas Jakarta M 24 08156210928 Jamalullail, S.IP, MM Universitas Jakarta M 25 091156200718 Dra. Dwi Murdiati, M.Hum. Universitas Jakarta M 26 091156202158 Dra. -

2020; Tanggal 18 Agustus 2020 Tentang Penetapan Peserta Lulus Seleksi Jalur Mandiri Tumou Tou (T2) Tahun 2020 Pada Universitas Sam Ratulangi

LAMPIRAN: KEPUTUSAN REKTOR UNIVERSITAS SAM RATULANGI NOMOR: 879/UN 12/PD/2020; TANGGAL 18 AGUSTUS 2020 TENTANG PENETAPAN PESERTA LULUS SELEKSI JALUR MANDIRI TUMOU TOU (T2) TAHUN 2020 PADA UNIVERSITAS SAM RATULANGI NOMOR TES NAMA PROGRAM STUDI PENDIDIKAN DOKTER (KBK) 120101070209 ABRAHAM DOTULUNG 120101160056 AMANDA NATASHA RORING 120101210406 ANANDA PRICILIA SAMBULELE 120101130051 BELLANTY COSTANTY TOGAS 120101020171 BRENDA WONGKAREN 120101100202 BYRGITA YOHANA PANGEMANAN 120101120229 CHINDY FERNANDA MONGDONG 120101120018 CLEVER CHRISTOVE LEARNT LONTAAN 120101050177 DWIPANIA GLORY SETIAWAN PUTRI 120101190248 ELSHADAI TAMPI 120101020045 ESTELINA IRENE BENJAMIN 120101070070 ESTER RIBCHANIA SERAN 120101080194 ESTERIN FELICIA ANAADA TATAWI 120101110088 EUPHEMIA LARASTIKA MANUMPIL 120101030115 FEIBY CIUAILEEN TOLIU 120101090173 FEYSIRA CRISTI EKA PUTRI KOWEL 120101040224 FIORENZA ANGELIKA KINDANGEN 120101080101 FRANSISKUS VALENTINO LANGI 120101100181 GISELA SONIA MONICA PITOY 120101060087 GLORIA PINLY REY 120101170025 GRIFFITH CHRISTIANE IMANUELA RUMAGIT 120101190087 GUINEVERE MIKHA VICTORIA PAENDONG 120101040147 HAHOLONGAN EVLYN REZKY PASARIBU 120101140141 HANA NASRANI ERKHOMAI NATALIA NGANTUNG 120101070109 IMANUELA MARETHA JULIA SEMBEL 120101150024 IMANUELA PUTRI TIWOUW 120101080183 ISHAK ALVITO ASSA 120101210566 JENIFER MAGDALENA BOLANG 120101100155 JOHANA ELISSA MAWIKERE 120101020069 JOHANES JUAN FERNANDO NGONGOLOY 120101140033 JOSEPH SIMKA GINTING 120101190132 KALISTA LUMENTE 120101060152 MARCHELLA RACHEL NANANGKONG 120101020163 MARDHITA -

General Nasution Brig.Jen Sarwo Edhie Let.Gen Kemal Idris Gen

30 General Nasution Brig.Jen Sarwo Edhie Let.Gen Kemal Idris Gen Simatupang Lt Gen Mokoginta Brig Jen Sukendro Let.Gen Mokoginta Ruslan Abdulgani Mhd Roem Hairi Hadi, Laksamana Poegoeh, Agus Sudono Harry Tjan Hardi SH Letjen Djatikusumo Maj.Gen Sutjipto KH Musto'in Ramly Maj Gen Muskita Maj Gen Alamsyah Let Gen Sarbini TD Hafas Sajuti Melik Haji Princen Hugeng Imam Santoso Hairi Hadi, Laksamana Poegoeh Subchan Liem Bian Kie Suripto Mhd Roem Maj.Gen Wijono Yassien Ron Hatley 30 General Nasution (24-7-73) Nasution (N) first suggested a return to the 1945 constitution in 1955 during the Pemilu. When Subandrio went to China in 1965, Nasution suggested that if China really wanted to help Indonesia, she should cut off supplies to Hongkong. According to Nasution, BK was serious about Maphilindo but Aidit convinced him that he was a world leader, not just a regional leader. In 1960 BK became head of Peperti which made him very influential in the AD with authority over the regional commanders. In 1962 N was replaced by Yani. According to the original concept, N would become Menteri Hankam/Panglima ABRI. However Omar Dhani wrote a letter to BK (probably proposed by Subandrio or BK himself). Sukarno (chief of police) supported Omar Dhani secara besar). Only Martadinata defended to original plan while Yani was 'plin-plan'. Meanwhile Nasution had proposed Gatot Subroto as the new Kasad but BK rejected this because he felt that he could not menguasai Gatot. Nas then proposed the two Let.Gens. - Djatikusuma and Hidayat but they were rejected by BK. -

Persepsi Masyarakat Terhadap Karakter Taman Kota Studi Kasus : Taman Menteri Supeno Di Semarang

4th International Symposium of NUSANTARA URBAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE (NURI) “CHANGE + HERITAGE IN ARCHITECTURE + URBAN DEVELOPMENT” November 7th, 2009, Architecture Department of Engineering Faculty, Diponegoro University, Tembalang Campuss Jl.Prof.H.Sudharto, SH, Semarang, Central Java, Indonesia Persepsi Masyarakat Terhadap Karakter Taman Kota Studi Kasus : Taman Menteri Supeno di Semarang Arief Aryo Adinata, ST1), Ir. Titien Woro Murtini, MSA2) ; Ir. Wijayanti, M.Eng3) Kota adalah merupakan wujud fisik yang Abstrak— Taman kota sebagai bagian dari ruang publik, dihasilkan oleh manusia dari waktu ke waktu yang sering tidak disadari oleh masyarakat kota akan bertungsi untuk mewadahi aktifitas hidup masyarakat kota peranannya di dalam menyelaraskan pola kehidupan kota yang kompleks dan luas. Oleh karena itu pertumbuhan yang sehat. Pemanfaatan ruang taman kota cenderung fisik kota sering menimbulkan permasalan bagi lingkungan rnenyimpang dari fungsinya, adanya perubahan aktifitas di perkotaan maupun sosial masyarakat kota. dalam taman menunjukan kekurang-pahaman masyarakat Salah satu kebutuhan kota adalah tersedianya kota di dalam memanfaatkan taman kota terhadap ruang-ruang terbuka untuk mewadahi kebutuhanan keseimbangan kehidupan lingkungan kota. masyarakat dalam melakukan aktifitas sekaligus untuk Makna yang sangat dalam mengenai kota yang mengendalikan kenyamanan iklim mikro dan keserasian berwawasan lingkungan adalah selalu menghadirkan estetikanya. taman yang hijau menjadi elemen utama yang tidak dapat Pada kenyataannya ruang terbuka di dalam kota ditinggalkan begitu saja. Bahkan karakter masyarakat sering terdesak oleh pertumbuhan massa dari gedung- sebuah kota dapat tercermin pada perilaku masyarakat kota gedung bangunan yang cenderung untuk menutup di dalam memanfaatkan taman kota. Begitu berperanya permukaan tanah sehingga dikhawatirkan terhadap taman kota terhadap pemenuhan kebutuhan masyarakat pengurangan infiltrasi air ke dalam tanah dan juga kota akan fasilitas ruang publik, sehingga memerlukan menimbulkan potensi iklim mikro menjadi panas. -

Indo 10 0 1107123622 195

194 Note: In addition to the positions shown on the chart, thepe are a number of other important agencies which are directly responsible to the Commander of the Armed Forces and his Deputy. These include the following: Strategic Intelligence Center, Institute of National Defense, Institute of Joint Staff and Command Education/Military Staff and Command College, Military Academy, Military Industries, Military Police, Military Prosecutor-General, Center of People’s Resistance and Security, and Information Center. CURRENT DATA ON THE INDONESIAN MILITARY ELITE AFTER THE REORGANIZATION OF 1969-1970 (Prepared by the Editors) Periodically in the past, the editors of Indonesia have prepared lists of the officers holding key positions in the Indonesian army to keep readers abreast of developments. (See the issues of April 1967, October 1967, and April 1969). Until very recently, the important changes meredy involved individual officers. But on Armed Forces Day, October 5, 1969, General Suharto announced a major structural reorganization of the military hierarchy, and these changes were put into effect between November 1969 and April 1970. According to the military authorities, MThe concept of reorganization, which is aimed at integrating the armed forces, arose in 1966 after the communist coup attempt of 1965. The idea was based on the view that developing countries suffer from political instability due to con flict between competing groups."1 On October 6, the then Chief of Staff of the Department of Defense and Security, Lt. Gen. Sumitro, said that the integration of the armed forces "will prevent the occurrence of situations like those in Latin America where the seizure of power is always accompanied by activities on the part of one of the armed forces or individuals from the armed forces."2 The main thrust of the reorganization (for details of which see the footnotes) is in the direction of greatly increased centraliza tion of control within the Department of Defense and Security. -

Agen Allianz Life Yang Berlisensi Syariah Aktif Per 31 Mei 2021.Pdf

DAFTAR AGEN YANG BERLISENSI SYARIAH AKTIF - AS OF 31 MEI 2021 NO AGENT_NAME LICENSE_NUMBER 1 A A AYU MANIK AW 3321012036482020 2 A ARI KARUNIAWAN 3321012006150020 3 A SALAM MUHAMMADONG 3321011025615319 4 A. A PUTU EKA PARYANTI 3321012008479521 5 A. BAROIL 3321012052451719 6 A. HARIS 3321012076460320 7 A. INDRA JAYA 14902553S 8 A. M. GANDA MARPAUNG 3321012010214720 9 A. M. YUDHISTIRA SEKUNDHITA 3321012010295421 10 A. RETNO KUSWARDHANI 3321012074445020 11 A. ROBITH SYA'BANI 3321012097213820 12 A. TIKA WIDYAWARDHANI 3321012044831519 13 A.D. KUSUMA WARDHANA 3321012002801320 14 AAN CHAERANI 3321011025616819 15 AAN DARMAWAN 3321012020846021 16 AAN DIANA 3321012064398519 17 AAN HANDOKO ANG 14443135S 18 AAN JUNAIDI 3321012027911420 19 AAN SAHIDA 3321012019837621 20 AANG YONDA ANGELA 11021161S 21 AARON ABIA JUNIAS 3321012051539419 22 AARON ADHIPUTRA WIJAYA 3321012028297020 23 AB ROHMAN 3321012016588221 24 ABANG IBNU SYAMSURIZAL 10063318S 25 ABBIET SUBIYAKTO 11075737S 26 ABD FAISAL HULA 14073438S 27 ABD HALIM 14897951S 28 ABD RHAKHMAN RAMLI 3321012001302720 29 ABDI ALAMSYAH HARAHAP 11328895S 30 ABDI SOMAD 3321012014853221 31 ABDILLAH PAHRESI 3321012031421720 32 ABDIUSTIAWAN 3321012097978220 33 ABDUL AZIS 3321012004080821 34 ABDUL AZIZ 3321012098577620 35 ABDUL FATAH 3321012091888520 36 ABDUL FIKRI GUNAWAN 3321012010309021 37 ABDUL HAKIM GALIB BELFAS 3321012016206421 38 ABDUL HARIS 14473674S 39 ABDUL HARIST GANI 3321012028298420 40 ABDUL JALIL 3321012001457020 41 ABDUL RACHMAN 14888820S 42 ABDUL RACHMAN N 3321012066747519 43 ABDUL RAHMAN 3321012038907219 -

Plagiat Merupakan Tindakan Tidak Terpuji

PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PERANAN SUDIRO DALAM PERJUANGAN KEMERDEKAAN INDONESIA TAHUN 1945 SKRIPSI Diajukan Untuk Memenuhi Salah Satu Syarat Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Pendidikan Program Studi Pendidikan Sejarah Oleh: Fransiska Ernawati NIM: 031314006 PROGRAM STUDI PENDIDIKAN SEJARAH JURUSAN PENDIDIKAN ILMU PENGETAHUAN SOSIAL FAKULTAS KEGURUAN DAN ILMU PENDIDIKAN UNIVERSITAS SANATA DHARMA YOGYAKARTA 2008 PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI ii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI iii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI MOTTO “Biarlah tanganmu menjadi penolongku, sebab aku memilih titah-titahmu” (MAZMUR 119 : 173) “Serahkanlah perbuatanmu kepada TUHAN, maka terlaksanalah segala perbuatanmu” (AMSAL 16 : 3) “Jangan ingatkan ketakutan anda, tetaplah ingat harapan dan impian anda. Jangan fikirkan frustasi anda, tetapi fikirkan potensi yang belum anda penuhi. Jangan khwatirkan diri anda sendiri dengan apa yang telah anda coba tapi gagal, tapi dengan apa yang masih mungkin anda lakukan ” (Paus Yohanes XXIII) iv PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PERSEMBAHAN Karya kecil ini kupersembahkan teruntuk : Tuhan Yesus Kristus yang senantiasa mendampingi, melindungi dan selalu memberikan segala hal yang terbaik dalam setiap langkah hidupku Bunda Maria yang sungguh baik hati Kedua orang tuaku yang tercinta, (Bapak Sugito Markus dan Ibu Senti Sihombing) Dan adik-adikku yang tersayang, (Sisilia Yuni Diliana dan Yulius Tri Setianto) v PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI vi PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI ABSTRAK Fransiska Ernawati : Peranan Sudiro Dalam Perjuangan Kemerdekaan Indonesia Tahun 1945. Penulisan skripsi ini bertujuan untuk mendeskripsikan dan menganalisis: (1) latar belakang pendidikan dan pengalaman politik (partai) dari Sudiro, (2) usaha-usaha Sudiro dalam suatu pergerakan kebangsaan sebelum perjuangan kemerdekaan Indonesia 17 Agustus 1945, (3) peranan dari Sudiro dalam pelaksanaan perjuangan kemerdekaan Indonesia tahun 1945. -

Students Shot Dead on Black Friday

Tapol bulletin no, 149/150, December 1998 This is the Published version of the following publication UNSPECIFIED (1998) Tapol bulletin no, 149/150, December 1998. Tapol bulletin (149). pp. 1-32. ISSN 1356-1154 The publisher’s official version can be found at Note that access to this version may require subscription. Downloaded from VU Research Repository https://vuir.vu.edu.au/25991/ ISSN 1356-1154 The Indonesia Human Rights Campaign TAPOL Bulletin No. 149/150 December 1998 Students shot dead on Black Friday Calls for ABRI to get out ofpolitics and for Suharto to be put on trial reverberated on the streets of Jakarta for a whole week as tens of thousands of students and hundreds of thousands of citizens protested against the Supreme Consultative Assembly (MPR) special session. On Black Friday, 13 November, eight students were slain as troops opened fire on peaceful demonstrators, almost six months to the day after student demonstrators forced the dictator, Suharto, to step down. The mass campaign against the MPR's special session sticks and unarmed students who resorted to throwing began on 28 October, when tens of thousands of students stones. Throughout the week, armoured vehicles and water demonstrated peacefully in Jakarta, protesting against the cannon supplied to the Indonesian armed forces by British meeting scheduled for 10-13 November and denouncing companies, were used to quell the protesters. the dwifungsi which gives ABRI, the armed forces unre In addition to the troops, the armed forces had hired stricted powers in all the affairs of state. gangs of men to join a vigilante brigade called PAM The demonstrations that began on 10 November grew Swakarsa armed with sharpened bamboo sticks (bambu in size as the week progressed. -

Research Study

*. APPROVED FOR RELEASE DATE:.( mY 2007 I, Research Study liWOlVEXZ4-1965 neCoup That Batkfired December 1968- i i ! This publication is prepared for tbe w of US. Cavernmeat officials. The formaf coverage urd contents of tbe puti+tim are designed to meet the specific requirements of those u~n.US. Covernment offids may obtain additional copies of this document directly or through liaison hl from the Cend InteIIigencx Agency. Non-US. Government usem myobtain this dong with rimikr CIA publications on a subscription bask by addressing inquiries to: Document Expediting (DOCEX) bject Exchange and Gift Division Library of Con- Washington, D.C ZOSaO Non-US. Gowrrrmmt users not interested in the DOCEX Project subscription service may purchase xeproductio~~of rpecific publications on nn individual hasis from: Photoduplication Servia Libmy of Congress W~hington,D.C. 20540 f ? INDONESIA - 1965 The Coup That Backfired December 1968 BURY& LAOS TMAILANO CAYBODIA SOUTU VICINAY PHILIPPIIEL b. .- .r4.n MALAYSIA INDONESIA . .. .. 4. , 1. AUSTRALIA JAVA Foreword What is commonly referred to as the Indonesian coup is more properly called "The 30 September Movement," the name the conspirators themselves gave their movement. In this paper, the term "Indonesian coup" is used inter- changeably with "The 30 September Movement ," mainly for the sake of variety. It is technically correct to refer to the events in lndonesia as a "coup" in the literal sense of the word, meaning "a sudden, forceful stroke in politics." To the extent that the word has been accepted in common usage to mean "the sudden and forcible overthrow - of the government ," however, it may be misleading. -

Kisah Tiga Jenderal Dalam Pusaran Peristiwa 11-Maret

KISAH TIGA JENDERAL DALAM PUSARAN PERISTIWA 11‐MARET‐1966 Bagian (1) “Kenapa menghadap Soeharto lebih dulu dan bukan Soekarno ? “Saya pertama‐tama adalah seorang anggota TNI. Karena Men Pangad gugur, maka yang menjabat sebagai perwira paling senior tentu adalah Panglima Kostrad. Saya ikut standard operation procedure itu”, demikian alasan Jenderal M. Jusuf. Tapi terlepas dari itu, Jusuf memang dikenal sebagai seorang dengan ‘intuisi’ tajam. 2014 Dan tentunya, juga punya kemampuan yang tajam dalam analisa June dan pembacaan situasi, dan karenanya memiliki kemampuan 21 melakukan antisipasi yang akurat, sebagaimana yang telah dibuktikannya dalam berbagai pengalamannya. Kali ini, kembali ia Saturday, bertindak akurat”. saved: Last TIGA JENDERAL yang berperan dalam pusaran peristiwa lahirnya Surat Perintah 11 Maret Kb) 1966 –Super Semar– muncul dalam proses perubahan kekuasaan dari latar belakang situasi (89 yang khas dan dengan cara yang khas pula. Melalui celah peluang yang juga khas, dalam suatu wilayah yang abu‐abu. Mereka berasal dari latar belakang berbeda, jalan pikiran dan 1966.docx ‐ karakter yang berbeda pula. Jenderal yang pertama adalah Mayor Jenderal Basuki Rachmat, dari Divisi Brawijaya Jawa Timur dan menjadi panglimanya saat itu. Berikutnya, yang kedua, Maret ‐ 11 Brigadir Jenderal Muhammad Jusuf, dari Divisi Hasanuddin Sulawesi Selatan dan pernah menjadi Panglima Kodam daerah kelahirannya itu sebelum menjabat sebagai menteri Peristiwa Perindustrian Ringan. Terakhir, yang ketiga, Brigadir Jenderal Amirmahmud, kelahiran Jawa Barat dan ketika itu menjadi Panglima Kodam Jaya. Pusaran Mereka semua mempunyai posisi khusus, terkait dengan Soekarno, dan kerapkali Dalam digolongkan sebagai de beste zonen van Soekarno, karena kedekatan mereka dengan tokoh puncak kekuasaan itu. Dan adalah karena kedekatan itu, tak terlalu sulit bagi mereka untuk Jenderal bisa bertemu Soekarno di Istana Bogor pada tanggal 11 Maret 1966. -

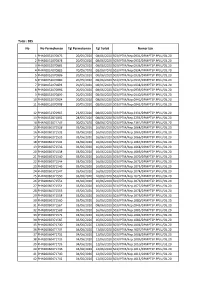

Recap Iptm 2020

Total : 985 No No Permohonan Tgl Permohonan Tgl Terbit Nomor Izin 1 PHN20052070875 20/05/2020 08/06/2020 503/IPTM/Kep.0931/DPMPTSP.PPJU/OL.20 2 PHN20052070878 20/05/2020 08/06/2020 503/IPTM/Kep.0932/DPMPTSP.PPJU/OL.20 3 PHN20052070881 20/05/2020 08/06/2020 503/IPTM/Kep.0933/DPMPTSP.PPJU/OL.20 4 PHN20052070883 20/05/2020 08/06/2020 503/IPTM/Kep.0934/DPMPTSP.PPJU/OL.20 5 PHN20052070886 20/05/2020 08/06/2020 503/IPTM/Kep.0935/DPMPTSP.PPJU/OL.20 6 PHN20052070889 20/05/2020 08/06/2020 503/IPTM/Kep.0937/DPMPTSP.PPJU/OL.20 7 PHN20052070893 20/05/2020 08/06/2020 503/IPTM/Kep.0938/DPMPTSP.PPJU/OL.20 8 PHN20052070896 20/05/2020 08/06/2020 503/IPTM/Kep.0939/DPMPTSP.PPJU/OL.20 9 PHN20052070899 20/05/2020 08/06/2020 503/IPTM/Kep.0940/DPMPTSP.PPJU/OL.20 10 PHN20052070904 20/05/2020 08/06/2020 503/IPTM/Kep.0941/DPMPTSP.PPJU/OL.20 11 PHN20052070908 20/05/2020 08/06/2020 503/IPTM/Kep.0942/DPMPTSP.PPJU/OL.20 12 PHN20052370965 23/05/2020 08/06/2020 503/IPTM/Kep.2331/DPMPTSP.PPJU/OL.20 13 PHN20052871092 28/05/2020 08/06/2020 503/IPTM/Kep.2293/DPMPTSP.PPJU/OL.20 14 PHN20053071247 30/05/2020 08/06/2020 503/IPTM/Kep.2361/DPMPTSP.PPJU/OL.20 15 PHN20060371528 03/06/2020 16/06/2020 503/IPTM/Kep.1064/DPMPTSP.PPJU/OL.20 16 PHN20060371531 03/06/2020 16/06/2020 503/IPTM/Kep.1065/DPMPTSP.PPJU/OL.20 17 PHN20060371533 03/06/2020 16/06/2020 503/IPTM/Kep.1066/DPMPTSP.PPJU/OL.20 18 PHN20060371534 03/06/2020 16/06/2020 503/IPTM/Kep.1067/DPMPTSP.PPJU/OL.20 19 PHN20060371536 03/06/2020 16/06/2020 503/IPTM/Kep.1068/DPMPTSP.PPJU/OL.20 20 PHN20060371538 03/06/2020 16/06/2020 503/IPTM/Kep.1069/DPMPTSP.PPJU/OL.20