Program Notes Amelia Bailey Distinguished Major Recital March 27Th, 2021 at 3:30Pm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Year's Music

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com fti E Y LAKS MV5IC 1896 juu> S-q. SV- THE YEAR'S MUSIC. PIANOS FOR HIRE Cramer FOR HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY Pianos BY All THE BEQUEST OF EVERT JANSEN WENDELL (CLASS OF 1882) OF NEW YORK Makers. 1918 THIS^BQQKJS FOR USE 1 WITHIN THE LIBRARY ONLY 207 & 209, REGENT STREET, REST, E.C. A D VERTISEMENTS. A NOVEL PROGRAMME for a BALLAD CONCERT, OR A Complete Oratorio, Opera Recital, Opera and Operetta in Costume, and Ballad Concert Party. MADAME FANNY MOODY AND MR. CHARLES MANNERS, Prima Donna Soprano and Principal Bass of Royal Italian Opera, Covent Garden, London ; also of 5UI the principal ©ratorio, dJrtlustra, artii Sgmphoiu) Cxmctria of ©wat Jfvitain, Jtmmca anb Canaba, With their Full Party, comprising altogether Five Vocalists and Three Instrumentalists, Are now Booking Engagements for the Coming Season. Suggested Programme for Ballad and Opera (in Costume) Concert. Part I. could consist of Ballads, Scenas, Duets, Violin Solos, &c. Lasting for about an hour and a quarter. Part II. Opera or Operetta in Costume. To play an hour or an hour and a half. Suggested Programme for a Choral Society. Part I. A Small Oratorio work with Chorus. Part II. An Operetta in Costume; or the whole party can be engaged for a whole work (Oratorio or Opera), or Opera in Costume, or Recital. REPERTOIRE. Faust (Gounod), Philemon and Baucis {Gounod) (by arrangement with Sir Augustus Harris), Maritana (Wallace), Bohemian Girl (Balfe), and most of the usual Oratorios, &c. -

Alla Zingarese August 5 and 6

Concert Program V: Alla Zingarese August 5 and 6 Friday, August 5 F RANZ JOSEph HAYDN (1732–1809) 8:00 p.m., Stent Family Hall, Menlo School Rondo all’ongarese (Gypsy Rondo) from Piano Trio in G Major, Hob. XV: 25 (1795) S Jon Kimura Parker, piano; Elmar Oliveira, violin; David Finckel, cello Saturday, August 6 8:00 p.m., The Center for Performing Arts at Menlo-Atherton HErmaNN SchULENBURG (1886–1959) AM Puszta-Märchen (Gypsy Romance and Czardas) (1936) PROgram OVERVIEW CharlES ROBERT VALDEZ A lifelong fascination with popular music of all kinds—espe- Serenade du Tzigane (Gypsy Serenade) cially the Gypsy folk music that Hungarian refugees brought to Germany in the 1840s—resulted in some of Brahms’s most ANONYMOUS cap tivating works. The music Brahms composed alla zinga- The Canary rese—in the Gypsy style—constitutes a vital dimension of his Wu Han, piano; Paul Neubauer, viola creative identity. Concert Program V surrounds Brahms’s lusty Hungarian Dances with other examples of compos- JOHANNES BrahmS (1833–1897) PROGR ERT ers drawing from Eastern European folk idioms, including Selected Hungarian Dances, WoO 1, Book 1 (1868–1869) C Hungarian Dance no. 1 in g minor; Hungarian Dance no. 6 in D-flat Major; the famous rondo “in the Gypsy style” from Joseph Haydn’s Hungarian Dance no. 5 in f-sharp minor G Major Piano Trio; the Slavonic Dances of Brahms’s pro- Wu Han, Jon Kimura Parker, piano ON tégé Antonín Dvorˇák; and Maurice Ravel’s Tzigane, a paean C to the Hun garian violin virtuoso Jelly d’Arányi. -

Bruno Walter (Ca

[To view this image, refer to the print version of this title.] Erik Ryding and Rebecca Pechefsky Yale University Press New Haven and London Frontispiece: Bruno Walter (ca. ). Courtesy of Österreichisches Theatermuseum. Copyright © by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections and of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Designed by Sonia L. Shannon Set in Bulmer type by The Composing Room of Michigan, Grand Rapids, Mich. Printed in the United States of America by R. R. Donnelley,Harrisonburg, Va. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ryding, Erik S., – Bruno Walter : a world elsewhere / by Erik Ryding and Rebecca Pechefsky. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references, filmography,and indexes. ISBN --- (cloth : alk. paper) . Walter, Bruno, ‒. Conductors (Music)— Biography. I. Pechefsky,Rebecca. II. Title. ML.W R .Ј—dc [B] - A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. For Emily, Mary, and William In memoriam Rachel Kemper and Howard Pechefsky Contents Illustrations follow pages and Preface xi Acknowledgments xv Bruno Schlesinger Berlin, Cologne, Hamburg,– Kapellmeister Walter Breslau, Pressburg, Riga, Berlin,‒ -

Ravel Compiled by David Barker

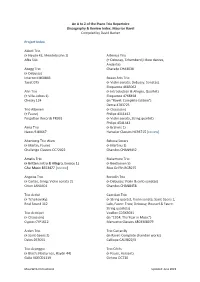

An A to Z of the Piano Trio Repertoire Discography & Review Index: Maurice Ravel Compiled by David Barker Project Index Abbot Trio (+ Haydn 43, Mendelssohn 1) Artenius Trio Afka 544 (+ Debussy, Tchemberdji: Bow dances, Andante) Abegg Trio Charade CHA3038 (+ Debussy) Intercord 860866 Beaux Arts Trio Tacet 075 (+ Violin sonata; Debussy: Sonatas) Eloquence 4683062 Ahn Trio (+ Introduction & Allegro, Quartet) (+ Villa-Lobos 1) Eloquence 4768458 Chesky 124 (in “Ravel: Complete Edition”) Decca 4783725 Trio Albeneri (+ Chausson) (+ Faure) Philips 4111412 Forgotten Records FR991 (+ Violin sonata, String quartet) Philips 4541342 Alma Trio (+ Brahms 1) Naxos 9.80667 Hanssler Classics HC93715 [review] Altenberg Trio Wien Bekova Sisters (+ Martin, Faure) (+ Martinu 1) Challenge Classics CC72022 Chandos CHAN9452 Amatis Trio Blakemore Trio (+ Britten: Intro & Allegro, Enescu 1) (+ Beethoven 5) CAvi Music 8553477 [review] Blue Griffin BGR275 Angelus Trio Borodin Trio (+ Cortes, Grieg: Violin sonata 2) (+ Debussy: Violin & cello sonatas) Orion LAN0401 Chandos CHAN8458 Trio Arché Caecilian Trio (+ Tchaikovsky) (+ String quartet, Violin sonata; Saint-Saens 1, Real Sound 112 Lalo, Faure: Trios; Debussy, Roussel & Faure: String quartets) Trio Archipel VoxBox CD3X3031 (+ Chausson) (in “1914: The Year in Music”) Cypres CYP1612 Menuetto Classics 4803308079 Arden Trio Trio Carracilly (+ Saint-Saens 2) (in Ravel: Complete chamber works) Delos DE3055 Calliope CAL3822/3 Trio Arpeggio Trio Cérès (+ Bloch: Nocturnes, Haydn 44) (+ Faure, Hersant) Gallo VDECD1119 Oehms -

The Piano Trio, the Duo Sonata, and the Sonatine As Seen by Brahms, Tchaikovsky, and Ravel

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: REVISITING OLD FORMS: THE PIANO TRIO, THE DUO SONATA, AND THE SONATINE AS SEEN BY BRAHMS, TCHAIKOVSKY, AND RAVEL Hsiang-Ling Hsiao, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2017 Dissertation directed by: Professor Rita Sloan School of Music This performance dissertation explored three significant piano trios, two major instrumental sonatas and a solo piano sonatine over the course of three recitals. Each recital featured the work of either Brahms, Tchaikovsky or Ravel. Each of these three composers had a special reverence for older musical forms and genres. The piano trio originated from various forms of trio ensemble in the Baroque period, which consisted of a dominating keyboard part, an accompanying violin, and an optional cello. By the time Brahms and Tchaikovsky wrote their landmark trios, the form had taken on symphonic effects and proportions. The Ravel Trio, another high point of the genre, written in the early twentieth century, went even further exploring new ways of using all possibilities of each instrument and combining them. The duo repertoire has come equally far: duos featuring a string instrument with piano grew from a humble Baroque form into a multifaceted, flexible classical form. Starting with Bach and continuing with Mozart and Beethoven, the form traveled into the Romantic era and beyond, taking on many new guises and personalities. In Brahms’ two cello sonatas, even though the cello was treated as a soloist, the piano still maintained its traditional prominence. In Ravel’s jazz-influenced violin sonata, he treated the two instruments with equal importance, but worked with their different natures and created an innovative sound combination. -

About the Music

ABOUT THE MUSIC Shadows and Sunshine | January 11, 12 & 13, 2020 Program notes by Steven Ledbetter | www.stevenledbetter.com MISSY MAZZOLI Sinfonia (for Orbiting Spheres) Missy Mazzoli was born in Lansdale, Pennsylvania, on October 27, 1980. Sinfonia (for Orbiting Spheres) was composed for chamber orchestra, and first performed by, the Los Angeles Philharmonic New Music Group, John Adams conducting, on April 8, 2014. An enlarged version was performed by the Boulder Philharmoinc, Michael Butterman conducting, on February 12, 2016. The score calls for pairs of flutes, oboes, clarinets and bassoons (doubling harmonicas), horns (doubling harmonicas), trumpets (doubling harmonicas), trombones (doubling harmonicas), one tuba, percussion for two players, piano (doubling synthesizer; organ sound) and strings. ABOUT THE MUSIC Missy Mazzoli, who can easily be called a superstar composer today on the strength of her growing list of powerfully- conceived works, including several operas, received her Bachelor’s degree at Boston University and a Master’s at Yale University, followed by additional study at the Royal Conservatory of the Hague. Her music has been performed widely by soloists such as pianist Emmanuel Ax, violinist Jennifer Koh, cellist Maya Beyser and mezzo Abigail Fischer; by ensembles like the Kronos Quartet, eighth blackbird, and the NOW Ensmble; and a growing list of major orchestras. She has also written three operas with librettist Royce Vavrek and has been commissioned to write a new work for the Metropolitan Opera (one of two women to receive such a commission) based on George Saunders’ recent, highly-successful novel Lincoln in the Bardo. Her description of Sinfonia (for Orbiting Spheres) captures the uniqueness of her conception of the piece. -

The Concurrent Prevalence of Modernism and Romanticism As Seen in the Operas Performed Between the World Wars and Exemplified in Ernst Krenek’S Jonny Spielt Auf

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 6-10-2020 The Concurrent Prevalence of Modernism and Romanticism as seen in the Operas Performed between the World Wars and Exemplified in Ernst Krenek’s Jonny Spielt Auf Nicole Fassold Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Fassold, Nicole, "The Concurrent Prevalence of Modernism and Romanticism as seen in the Operas Performed between the World Wars and Exemplified in Ernst Krenek’s Jonny Spielt Auf" (2020). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 5301. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/5301 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE CONCURRENT PREVALENCE OF MODERNISM AND ROMANTICISM AS SEEN IN THE OPERAS PERFORMED BETWEEN THE WORLD WARS AND EXEMPLIFIED IN ERNST KRENEK’S JONNY SPIELT AUF A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The College of Music and Dramatic Arts by Nicole Fassold B.M., Colorado State University, 2015 M.M., University of Delaware, 2017 August 2020 Acknowledgements I would like to express my deepest gratitude to the professors and panel members that have guided me throughout my Doctoral studies as well as to my parents and sister, my family all over the world, my friends, and my incredible husband for their unending support and encouragement. -

French Violin Performance from Franck to Ravel A

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles In Search of a Style: French Violin Performance from Franck to Ravel A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Musical Arts by Ji Young An 2013 © Copyright by Ji Young An 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION In Search of a Style: French Violin Performance from Franck to Ravel by Ji Young An Doctor of Musical Arts University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Robert Winter, Chair My dissertation focuses on issues of French sound and style in late nineteenth and early twentieth-century French violin repertoire. As a violinist who studied at the Paris Conservatory, I have long been puzzled as to why so little had been written about something that everyone seems to take for granted—so called French style. I attacked this elusive issue from three perspectives: 1) a detailed look at performance directions; 2) comparisons among recordings by artists close to this period (Jacques Thibaud, Zino Francescatti, as well as contemporary French artists such as Philippe Graffin and Guillaume Sutre); and 3) interviews with three living French violinists (Olivier Charlier, Régis Pasquier, and Gérard Poulet) with strong ties to this tradition. After listening to countless historical recordings, I settled on three pivotal works that illustrate the emergence and full flowering of the French style: César Franck’s Violin Sonata (1886), Claude Debussy’s Violin Sonata (1917), and ii Maurice Ravel’s Tzigane: Rapsodie de Concert pour Violon et Piano (1924). Each of them presents specific challenges: notational and stylistic issues in Franck’s Violin Sonata, Debussy’s performance directions in his Violin Sonata, and notational and interpretive issues in Ravel’s Tzigane that led to a separate, orally-transmitted French tradition. -

Ronen Chamber Ensemble and Virginie Robilliard February 26, 2008 PROGRAM NOTES

Ronen Chamber Ensemble and Virginie Robilliard 1990 Laureate of the International Violin Competition of Indianapolis February 26, 2008 PROGRAM NOTES Ernest Chausson (1855-1899): Poème for violin and piano, Op. 25 Notes by Cathleen Partlow Strauss Chausson was one of those fortunates who was independently wealthy and could therefore work at his art at his own pace. He produced relatively few works, never worrying about success as a professional musician. Although he started his university studies in law, he soon turned to music. He briefly studied with Massenet at the Paris Conservatory, and later continued as a private student of César Franck. The influence of Franck, as well as Wagner, is evident in much of his work. He had just begun to achieve some degree of critical acclaim, in large part due to successful performances of his Poème and his only symphony, when he was killed in bizarre fashion in a bicycle accident. Chausson wrote Poème, in its original form for violin and orchestra, in 1896 for the famous Belgian violinist Eugène Ysaÿe. It had its first performance in Paris on April 4, 1897. The music was inspired after Chausson read a short story by Ivan Turgenev (1818-1883), entitled "The Song of Triumphant Love." Part of the story is exotic in setting, and has, as a central feature, a prominent story-line about a violin. This exoticism is revealed by Chausson’s impression of Eastern music. It is at the heart of the late French Romantic aesthetic and is a gorgeous and opulent work. The rhapsodic piece is half the length of a traditional concerto, with more freedom inherent in the structure. -

Irreverent Reverence Saturday, February 6, 2016 • 7:30 PM First Free Methodist Church

Irreverent Reverence Saturday, February 6, 2016 • 7:30 PM First Free Methodist Church Orchestra Seattle Seattle Chamber Singers Clinton Smith, conductor JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833 – 1897) Academic Festival Overture, Op. 80 Allegro — L’istesso tempo, un poco maestoso — Animato — Maestoso JEAN SIBELIUS (1865 – 1957) Violin Concerto in D minor, Op. 47 I. Allegro moderato — Largamente — Allegro molto — Moderato assai — Allegro moderato — Allegro molto vivace Adrian Steele, violin — intermission — GABRIEL FAURE´ (1845 – 1924) Requiem in D minor, Op. 48 Introitus et Kyrie Offertorium Sanctus Pie Jesu Agnus Dei Libera me In paradisum Karina Brazas, soprano Ryan Bede, baritone Please silence cell phones and other electronics, and refrain from the use of cameras and recording devices during the performance. Special thanks to First Free Methodist Church for all of their assistance in making OSSCS’s 46th season possible, and for providing refreshments during intermission. Donations left at the refreshments tables help support FFMC and its programs. Orchestra Seattle • Seattle Chamber Singers Clinton Smith, music director • George Shangrow, founder PO Box 15825, Seattle WA 98115 • 206-682-5208 • www.osscs.org Violin Bassoon Pamela Ivezicˇ Bass Lauren Daugherty+ Jeff Eldridge Jan Kinney Timothy Braun Dean Drescher Judith Lawrence* Lorelette Knowles Greg Canova Karen Frankenfeld+ Theodora Letz Andrew Danilchik Alexander Hawker Contrabassoon Lila Woodruff May Douglas Durasoff Stephen Hegg Michel Jolivet Laurie Medill x Daniel Hericks Jason Hershey Cathrine Morrison Stephen Keeler Horn Manchung Ho+ Annie Thompson Dennis Moore Barney Blough Maria Hunt Brittany Walker Steven Tachell Laurie Heidt* Fritz Klein** Skip Viau Jim Hendrickson Pam Kummert Tenor Richard Wyckoff x Sue Perry Mark Lutz Ron Carson Davis Reed Trumpet Alex Chun Theo Schaad Rabi Lahiri Ralph Cobb x Lily Shababi Oscar Thorp Jon Lange Janet Showalter* Janet Young* German Mendoza Jr. -

February 13, 2021

Romance February 13, 2021 Photo: Jeffery Noble Romance Saturday, February 13, 2021 • 7:30PM Peoria Civic Center Theater Peoria Symphony Orchestra George Stelluto · conductor The Romaniacs Masha Lakisova · violin Michelle Areyzaga · soprano Roma Fantasy Anton Bruckner (1824-1896) arr. G. Stelluto Zigeunerweisen, Op. 20 Pablo de Sarasate (1844-1908) Masha Lakisova • violin Djangology Django Reinhardt (1910-1953)/arr. P. Ekdahl The Romaniacs Drei Zigeuner Lieder Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) He, Zigeuner, greife in die Saiten (Op. 103, No. 1) Liebe Schwalbe, Kleine Schwalbe (Op. 112, No. 6) Röslein dreie in der Reihe (Op. 103, No. 7) Michelle Areyzaga • soprano Masha Lakisova • soprano For Sephora Stochelo Rosenberg (b. 1968) arr. A.Girardo Nuages Django Reinhardt arr. P. Ekdahl The Romaniacs Tzigane Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) Masha Lakisova • violin INTERMISSION Manoir de mes rêves Django Reinhardt/arr. P. Ekdahl The Romaniacs Romancero Gitano, Op. 152 Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco (1895-1968) arr. G. Stelluto The Romaniacs with Michelle Areyzaga • soprano Tears Django Reinhardt arr. P. Ekdahl Creve Coeur (world premiere) John Miller arr. G. Stelluto Bellville Django Reinhardt arr. P. Ekdahl The Romaniacs Concert Sponsors & Underwriters Carl W. Soderstrom, MD The Meredith Foundation This program is partially supported by a Conductor’s Circle grant from the Illinois Arts Council Agency. 57 The Romaniacs John Miller started playing at the age of nine. During the 1970s, John toured with Chicago crooner Jimmy Damon, and later toured with pop star Dobie Gray (“The In Crowd” and “Drift Away”). For years he was well-known in Peoria as a private lesson teacher and performer. His credits include performing in orchestral settings with Bob Hope, Tom Jones, Rich Little, and Cab Calloway. -

Orchestre Symphonique De Montréal / Giancarlo Guerrero

AYANA TSUJI Winner of the 2016 Concours Musical International de Montréal Final round: First Prize JEAN SIBELIUS 1865–1957 Violin Concerto in D minor, Op.47 1 I. Allegro moderato 16.55 2 II. Adagio di molto 8.31 3 III. Allegro, ma non tanto 8.13 from the Quarter-final round: Bach Award (best performance of a work by J.S. Bach) Paganini Award (best performance of a Paganini Caprice) CAMILLE SAINT-SAËNS 1835–1921 4 Introduction et Rondo capriccioso in A minor, Op.28 9.41 Piano reduction by Georges Bizet (ed. Zino Francescatti) from the Semi-final round: Best Performance of a Sonata · Best Semi-final Recital André-Bachand Award (best performance of the compulsory Canadian work) IGOR STRAVINSKY 1882–1971 Duo concertant 5 I. Cantilène 3.03 6 II. Églogue I 2.18 7 III. Églogue II 2.52 8 IV. Gigue 4.17 9 V. Dithyrambe 3.34 59.42 AYANA TSUJI violin Orchestre symphonique de Montréal / Giancarlo Guerrero (1–3) Philip Chiu piano (4–9) « Je souhaiterais remercier chaleureusement Christiane LeBlanc, directrice générale et artistique du Concours musical international de Montréal pour son soutien indéfectible, son amour de la musique classique et son engagement sans faille auprès des jeunes artistes ainsi, que toute son équipe, Scott Tresham et Dina Barghout en particulier; Luc Fortin, Président de la GMMQ et Louis Leclerc, Directeur des relations de travail à la GMMQ sans l’intervention, la compréhension et l’aide desquels le projet n’aurait jamais vu le jour; Marie-Josée Desrochers et Sébastien Almon de l’Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal pour leur professionnalisme, leur gentillesse et leur efficacité; Sylvie Bouchard et Aurélie Abdeljebar de l’agence artistique Kajimoto, celles par qui tout a commencé.