Ronen Chamber Ensemble and Virginie Robilliard February 26, 2008 PROGRAM NOTES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alla Zingarese August 5 and 6

Concert Program V: Alla Zingarese August 5 and 6 Friday, August 5 F RANZ JOSEph HAYDN (1732–1809) 8:00 p.m., Stent Family Hall, Menlo School Rondo all’ongarese (Gypsy Rondo) from Piano Trio in G Major, Hob. XV: 25 (1795) S Jon Kimura Parker, piano; Elmar Oliveira, violin; David Finckel, cello Saturday, August 6 8:00 p.m., The Center for Performing Arts at Menlo-Atherton HErmaNN SchULENBURG (1886–1959) AM Puszta-Märchen (Gypsy Romance and Czardas) (1936) PROgram OVERVIEW CharlES ROBERT VALDEZ A lifelong fascination with popular music of all kinds—espe- Serenade du Tzigane (Gypsy Serenade) cially the Gypsy folk music that Hungarian refugees brought to Germany in the 1840s—resulted in some of Brahms’s most ANONYMOUS cap tivating works. The music Brahms composed alla zinga- The Canary rese—in the Gypsy style—constitutes a vital dimension of his Wu Han, piano; Paul Neubauer, viola creative identity. Concert Program V surrounds Brahms’s lusty Hungarian Dances with other examples of compos- JOHANNES BrahmS (1833–1897) PROGR ERT ers drawing from Eastern European folk idioms, including Selected Hungarian Dances, WoO 1, Book 1 (1868–1869) C Hungarian Dance no. 1 in g minor; Hungarian Dance no. 6 in D-flat Major; the famous rondo “in the Gypsy style” from Joseph Haydn’s Hungarian Dance no. 5 in f-sharp minor G Major Piano Trio; the Slavonic Dances of Brahms’s pro- Wu Han, Jon Kimura Parker, piano ON tégé Antonín Dvorˇák; and Maurice Ravel’s Tzigane, a paean C to the Hun garian violin virtuoso Jelly d’Arányi. -

Program Notes Amelia Bailey Distinguished Major Recital March 27Th, 2021 at 3:30Pm

Program Notes Amelia Bailey Distinguished Major Recital March 27th, 2021 at 3:30pm Roma Folk Dances: Villages Tunes of the Hungarian Roma. Daniel Sender (1982-) I. Ha elvettél, tartsá (Öcsöd) II. I canka uj Anna (Püspökladány) III. Hallgató (Mezókovácsháza) for Violin Solo IV. Ének (Püspökladány) V. Jaj, anyám, a vakaró (Csenyéte) Daniel Sender is currently the concertmaster of the Charlottesville Symphony and the Charlottesville Opera, as well as associate violin professor at UVA. Sender studied at Ithaca College, the University of Maryland–where he received his PhD, the Liszt Academy (Budapest) and the Institute for European Studies (Vienna). His scholarship in Hungarian music began when he was awarded a Fulbright Student Scholar grant for his research in Budapest (2010-11), where he attended the Liszt Academy as a student of Vilmos Szabadi and became interested in Hungarian Roma folk music. (Note: unless otherwise stated, assume “Hungary” in terms of folk music geographically refers to the late Austro-Hungarian Empire which existed prior to the Treaty of Trianon. At the end of WWI, the Treaty of Trianon split 75% of Austro-Hungary’s territory up into modern day Romania, Czechoslovakia, Austria, and the Balkans.) The Roma people in Hungary–also known as Romani people, and previously, “gypsies,” though that term is now considered outdated slang, are the largest minority group in Hungary, making up between 3 and 7% of the population. There is a clear cultural divide between those who consider themselves native Hungarians, and Roma people. A large proportion of the Roma population lives in extreme poverty and faces constant racial discrimination, while the European Union and Hungarian officials are only just beginning to take accountability. -

Ravel Compiled by David Barker

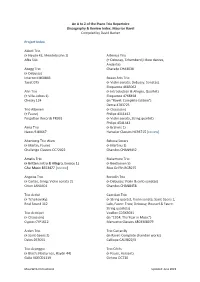

An A to Z of the Piano Trio Repertoire Discography & Review Index: Maurice Ravel Compiled by David Barker Project Index Abbot Trio (+ Haydn 43, Mendelssohn 1) Artenius Trio Afka 544 (+ Debussy, Tchemberdji: Bow dances, Andante) Abegg Trio Charade CHA3038 (+ Debussy) Intercord 860866 Beaux Arts Trio Tacet 075 (+ Violin sonata; Debussy: Sonatas) Eloquence 4683062 Ahn Trio (+ Introduction & Allegro, Quartet) (+ Villa-Lobos 1) Eloquence 4768458 Chesky 124 (in “Ravel: Complete Edition”) Decca 4783725 Trio Albeneri (+ Chausson) (+ Faure) Philips 4111412 Forgotten Records FR991 (+ Violin sonata, String quartet) Philips 4541342 Alma Trio (+ Brahms 1) Naxos 9.80667 Hanssler Classics HC93715 [review] Altenberg Trio Wien Bekova Sisters (+ Martin, Faure) (+ Martinu 1) Challenge Classics CC72022 Chandos CHAN9452 Amatis Trio Blakemore Trio (+ Britten: Intro & Allegro, Enescu 1) (+ Beethoven 5) CAvi Music 8553477 [review] Blue Griffin BGR275 Angelus Trio Borodin Trio (+ Cortes, Grieg: Violin sonata 2) (+ Debussy: Violin & cello sonatas) Orion LAN0401 Chandos CHAN8458 Trio Arché Caecilian Trio (+ Tchaikovsky) (+ String quartet, Violin sonata; Saint-Saens 1, Real Sound 112 Lalo, Faure: Trios; Debussy, Roussel & Faure: String quartets) Trio Archipel VoxBox CD3X3031 (+ Chausson) (in “1914: The Year in Music”) Cypres CYP1612 Menuetto Classics 4803308079 Arden Trio Trio Carracilly (+ Saint-Saens 2) (in Ravel: Complete chamber works) Delos DE3055 Calliope CAL3822/3 Trio Arpeggio Trio Cérès (+ Bloch: Nocturnes, Haydn 44) (+ Faure, Hersant) Gallo VDECD1119 Oehms -

The Piano Trio, the Duo Sonata, and the Sonatine As Seen by Brahms, Tchaikovsky, and Ravel

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: REVISITING OLD FORMS: THE PIANO TRIO, THE DUO SONATA, AND THE SONATINE AS SEEN BY BRAHMS, TCHAIKOVSKY, AND RAVEL Hsiang-Ling Hsiao, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2017 Dissertation directed by: Professor Rita Sloan School of Music This performance dissertation explored three significant piano trios, two major instrumental sonatas and a solo piano sonatine over the course of three recitals. Each recital featured the work of either Brahms, Tchaikovsky or Ravel. Each of these three composers had a special reverence for older musical forms and genres. The piano trio originated from various forms of trio ensemble in the Baroque period, which consisted of a dominating keyboard part, an accompanying violin, and an optional cello. By the time Brahms and Tchaikovsky wrote their landmark trios, the form had taken on symphonic effects and proportions. The Ravel Trio, another high point of the genre, written in the early twentieth century, went even further exploring new ways of using all possibilities of each instrument and combining them. The duo repertoire has come equally far: duos featuring a string instrument with piano grew from a humble Baroque form into a multifaceted, flexible classical form. Starting with Bach and continuing with Mozart and Beethoven, the form traveled into the Romantic era and beyond, taking on many new guises and personalities. In Brahms’ two cello sonatas, even though the cello was treated as a soloist, the piano still maintained its traditional prominence. In Ravel’s jazz-influenced violin sonata, he treated the two instruments with equal importance, but worked with their different natures and created an innovative sound combination. -

The Concurrent Prevalence of Modernism and Romanticism As Seen in the Operas Performed Between the World Wars and Exemplified in Ernst Krenek’S Jonny Spielt Auf

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 6-10-2020 The Concurrent Prevalence of Modernism and Romanticism as seen in the Operas Performed between the World Wars and Exemplified in Ernst Krenek’s Jonny Spielt Auf Nicole Fassold Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Fassold, Nicole, "The Concurrent Prevalence of Modernism and Romanticism as seen in the Operas Performed between the World Wars and Exemplified in Ernst Krenek’s Jonny Spielt Auf" (2020). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 5301. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/5301 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE CONCURRENT PREVALENCE OF MODERNISM AND ROMANTICISM AS SEEN IN THE OPERAS PERFORMED BETWEEN THE WORLD WARS AND EXEMPLIFIED IN ERNST KRENEK’S JONNY SPIELT AUF A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The College of Music and Dramatic Arts by Nicole Fassold B.M., Colorado State University, 2015 M.M., University of Delaware, 2017 August 2020 Acknowledgements I would like to express my deepest gratitude to the professors and panel members that have guided me throughout my Doctoral studies as well as to my parents and sister, my family all over the world, my friends, and my incredible husband for their unending support and encouragement. -

French Violin Performance from Franck to Ravel A

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles In Search of a Style: French Violin Performance from Franck to Ravel A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Musical Arts by Ji Young An 2013 © Copyright by Ji Young An 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION In Search of a Style: French Violin Performance from Franck to Ravel by Ji Young An Doctor of Musical Arts University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Robert Winter, Chair My dissertation focuses on issues of French sound and style in late nineteenth and early twentieth-century French violin repertoire. As a violinist who studied at the Paris Conservatory, I have long been puzzled as to why so little had been written about something that everyone seems to take for granted—so called French style. I attacked this elusive issue from three perspectives: 1) a detailed look at performance directions; 2) comparisons among recordings by artists close to this period (Jacques Thibaud, Zino Francescatti, as well as contemporary French artists such as Philippe Graffin and Guillaume Sutre); and 3) interviews with three living French violinists (Olivier Charlier, Régis Pasquier, and Gérard Poulet) with strong ties to this tradition. After listening to countless historical recordings, I settled on three pivotal works that illustrate the emergence and full flowering of the French style: César Franck’s Violin Sonata (1886), Claude Debussy’s Violin Sonata (1917), and ii Maurice Ravel’s Tzigane: Rapsodie de Concert pour Violon et Piano (1924). Each of them presents specific challenges: notational and stylistic issues in Franck’s Violin Sonata, Debussy’s performance directions in his Violin Sonata, and notational and interpretive issues in Ravel’s Tzigane that led to a separate, orally-transmitted French tradition. -

February 13, 2021

Romance February 13, 2021 Photo: Jeffery Noble Romance Saturday, February 13, 2021 • 7:30PM Peoria Civic Center Theater Peoria Symphony Orchestra George Stelluto · conductor The Romaniacs Masha Lakisova · violin Michelle Areyzaga · soprano Roma Fantasy Anton Bruckner (1824-1896) arr. G. Stelluto Zigeunerweisen, Op. 20 Pablo de Sarasate (1844-1908) Masha Lakisova • violin Djangology Django Reinhardt (1910-1953)/arr. P. Ekdahl The Romaniacs Drei Zigeuner Lieder Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) He, Zigeuner, greife in die Saiten (Op. 103, No. 1) Liebe Schwalbe, Kleine Schwalbe (Op. 112, No. 6) Röslein dreie in der Reihe (Op. 103, No. 7) Michelle Areyzaga • soprano Masha Lakisova • soprano For Sephora Stochelo Rosenberg (b. 1968) arr. A.Girardo Nuages Django Reinhardt arr. P. Ekdahl The Romaniacs Tzigane Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) Masha Lakisova • violin INTERMISSION Manoir de mes rêves Django Reinhardt/arr. P. Ekdahl The Romaniacs Romancero Gitano, Op. 152 Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco (1895-1968) arr. G. Stelluto The Romaniacs with Michelle Areyzaga • soprano Tears Django Reinhardt arr. P. Ekdahl Creve Coeur (world premiere) John Miller arr. G. Stelluto Bellville Django Reinhardt arr. P. Ekdahl The Romaniacs Concert Sponsors & Underwriters Carl W. Soderstrom, MD The Meredith Foundation This program is partially supported by a Conductor’s Circle grant from the Illinois Arts Council Agency. 57 The Romaniacs John Miller started playing at the age of nine. During the 1970s, John toured with Chicago crooner Jimmy Damon, and later toured with pop star Dobie Gray (“The In Crowd” and “Drift Away”). For years he was well-known in Peoria as a private lesson teacher and performer. His credits include performing in orchestral settings with Bob Hope, Tom Jones, Rich Little, and Cab Calloway. -

Download Program Notes

Shéhérazade, Three Poems of Tristan Klingsor for Voice and Orchestra Maurice Ravel taste for the exotic surfaces often in the The song-cycle Shéhérazade evolved out A catalogue of Maurice Ravel. He was 14 of the composer’s intention to write an opera years old in 1889, when the International Ex- based on the Sinbad episode from the Arabi- hibition astonished le tout Paris with such an Nights. Scheherazade is both the narrator musical attractions as a Javanese gamelan, a and heroine of that work, spinning out tale Hungarian gypsy ensemble, and a troupe of after tale because her life depends on it. Ravel Annamite dancers from Vietnam. If Claude never finished the opera, but he did com- Debussy was the first major composer to in- plete its overture, which was performed at a corporate some of those newly heard sounds concert of the Société Nationale in Paris on into his compositions, Ravel, 13 years his ju- May 27, 1899, to mild success. The piece was nior, would not be far behind. never published, and Ravel may have recy- Spain was the exotic milieu that surfaced cled some of its material into the song cycle most often in his oeuvre, although several of he composed four years later. So said Ravel’s such works — Alborada del gracioso (1904–05), pupil and biographer Alexis Roland-Manuel, Rapsodie espagnole and the opera L’Heure es- although scholars today find that any resem- pagnole (both from 1907), and the ever-popu- blance is slight. lar Boléro (1928) — may sound more redolent of faraway places today than they did to Rav- el, who hailed from a town practically on the In Short border between France and Spain and whose Born: March 7, 1875, in Ciboure, France mother was of Basque heritage. -

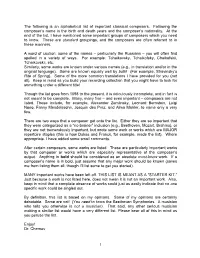

1 the Following Is an Alphabetical List of Important Classical Composers

The following is an alphabetical list of important classical composers. Following the composer’s name is the birth and death years and the composer’s nationality. At the end of the list, I have mentioned some important groups of composers which you need to know. These are standard groupings, and the composers are often referred to in these manners. A word of caution: some of the names – particularly the Russians – you will often find spelled in a variety of ways. For example: Tchaikovsky, Tchaikofsky, Chaikofskii, Tchaikovskii, etc. Similarly, some works are known under various names (e.g., in translation and/or in the original language). Some are known equally well by both! (For example, Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring). Some of the more common translations I have provided for you (not all). Keep in mind as you build your recording collection that you might have to look for something under a different title! Though the list goes from 1098 to the present, it is ridiculously incomplete, and in fact is not meant to be complete. Many, many fine – and even important – composers are not listed. These include, for example, Alexander Zemlinsky, Leonard Bernstein, Luigi Nono, Fanny Mendelssohn, Josquin des Prez, and Alma Mahler, to name only a very few. There are two ways that a composer got onto the list. Either they are so important that they were categorized as a “no-brainer” inclusion (e.g., Beethoven, Mozart, Brahms), or they are not tremendously important, but wrote some work or works which are MAJOR repertoire staples (this is how Dukas and Franck, for example, made the list). -

Ravel Tzigane Imslp

Ravel tzigane imslp Continue Joseph Maurice Ravel ʒozɛf mɔʁis ʁavɛl is a French composer, pianist and conductor. He is often associated with Impressionism with his elder contemporary Claude Debussy, although both composers rejected the term. In the 1920s and 1930s, Ravel was considered France's greatest living composer. Born into a musical-loving family, Ravel studied at the Royal College of Music of France, the Paris Conservatory; he was not well regarded by his conservative establishment, whose bias against him caused a scandal. After leaving the conservatory, Ravel found his own way as a composer, developing a style of great clarity that included elements of baroque, neoclassicism and, in his later works, jazz. He liked to experiment with the musical form, as in his most famous work, Bolero (1928), in which repetition takes the place of development. He made several orchestral arrangements of music by other composers, of which his version of Mussorgsky's 1922 paintings on the exhibition is the most famous. As a slow and painstaking worker, Ravel composed fewer works than many of his contemporaries. His works included piano pieces, chamber music, two piano concerts, ballet music, two operas (each less than an hour) and eight song cycles; he wrote no symphonies and only one religious work (Kaddish). Many of his works exist in two versions: first the piano score and then the orchestration. Some of his piano music, such as Gaspar de la Nuit (1908), are exceptionally difficult to play, and his intricate orchestral works such as Daphnis and Chloe (1912) require a skilful balance in performance. -

Ravel AUS:556673Bk Ravel AUS 6/29/08 12:46 PM Page 2

556673bk Ravel AUS:556673bk Ravel AUS 6/29/08 12:46 PM Page 2 Piano Music The Best of... Ravel was himself a good pianist. His music for the piano includes Prokofiev 8.556681 The Best of compositions in his own nostalgic archaic style, such as the Pavane and J. S. Bach 8.556656 Puccini 8.556670 the Menuet antique, as well as the more complex textures of pieces such as Jeux d’eau (Fountains), Miroirs and Gaspard de la nuit, with its sinister Beethoven 8.556651 Rachmaninov 8.556682 RAVEL connotations. The Sonatina is in Ravel’s neo-classical style and Le Berlioz 8.556678 Ravel 8.556673 tombeau de Couperin is in the form of a Baroque dance suite. Bizet 8.556671 Rimsky-Korsakov 8.556674 ✓ Recommended Recordings Brahms 8.556659 Rossini 8.556683 DDD Boléro Piano Music Vol. 1 (Pavane; Jeux d’eau; Miroirs; Sonatine) Chopin 8.556654 Saint-Saëns 8.556675 Pavane pour Naxos 8.550683 Debussy 8.556663 Schubert 8.556666 une infante Piano Music Vol. 2 (Valses nobles et sentimentales; Gaspard de la nuit; défunte Le tombeau de Couperin; La valse) Dvorˇák 8.556661 Schumann 8.556662 Naxos 8.553008 Elgar 8.556672 Shostakovich 8.556684 Alborada del gracioso Fauré 8.556679 Sibelius 8.556677 Rapsodie Grieg 8.556658 Johann Strauss II 8.556664 espagnole Handel 8.556665 Stravinsky 8.556685 Tzigane Haydn 8.556668 Tchaikovsky 8.556652 Liszt 8.556667 Verdi 8.556669 Le Tombeau de Couperin Mendelssohn 8.556660 Vivaldi 8.556655 Mozart 8.556653 Wagner 8.556657 and others Paganini 8.556680 Weber 8.556676 5 8.556673 8.556673 556673bk Ravel AUS:556673bk Ravel AUS 6/29/08 12:46 PM Page 1 ✓ Maurice Ravel 1875 - 1937 Recommended Recordings Vocal Music Boléro; Daphnis et Chloé Suite No. -

Ravel Chronologie Marnat.Pdf

1875-1937 CHRONOLOGIE et Maurice Ravel Publiée par Jean Roy dans le premier numéro des Cahiers Maurice Ravel (1985), cette Chronologie devait servir de cadre général aux documents (lettres, interviewes retrouvées, photos…) que, sous sa férule, l’ entreprise se donna mission de publier. Jean Roy1 précisait, d’ entrée de jeu, ce que ce travail devait à l’ouvrage décisif de M. Arbie Orenstein (Ravel, Man and Musicien, Columbia University Press, New York 1968, régulièrement réédité depuis). 16 numéros de Cahiers Maurice Ravel ont, depuis, vu le jour, plus ou moins régulierement, du fait de changements de gestion (ce sont les éditions Séguier qui, depuis 2004, en assument la continuité, la diffusion etant confiée à Harmonia Mundi). Reste qu’on doit aujourd’hui tenir compte de cet apport considérable, publié jusqu’à tout récemment sous l’ autorité de M. Michel Delahaye. Les découvertes personnelles de M. Manuel Cornejo et la destinée plus internationale du présent Site exigent, désormais, une réélaboration complète de ce texte initial avec des ouvertures vers les événements politiques (notamment après la Première Guerre Mondiale, Ravel y puisant de subtiles réactions) et la création artistique (extraordinaire fécondité de toute la période). Quelques notes sur certains lieux ou personnages oubliés, enfin, ont paru nécessaires. Précisons pour finir que ce travail s’ augmente du film complet de toutes les activités musicales de Maurice Ravel (liste développée, précisée et matriculée2 -Catalogue Mt.- ainsi que les travaux d’Arbie Orenstein nous avaient permis de le faire pour notre propre monographie, publiée en 1986. M.Mt 1 Haut fonctionnaire, Jean Roy (1916-2011) fut un fin commentateur de la musique française.