Ravel Tzigane Imslp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Harmony and Timbre in Maurice Ravel's Cycle Gaspard De

Miljana Tomić The role of harmony and timbre in Maurice Ravel’s cycle Gaspard de la Nuit in relation to form A thesis submitted to Music Theory Department at Norwegian Academy of Music in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master’s in Applied Music Theory Spring 2020 Copyright © 2020 Miljana Tomić All rights reserved ii I dedicate this thesis to all my former, current, and future students. iii Gaspard has been a devil in coming, but that is only logical since it was he who is the author of the poems. My ambition is to say with notes what a poet expresses with words. Maurice Ravel iv Table of contents I Introduction ............................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Preface ........................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Presentation of the research questions ..................................................................... 1 1.3 Context, relevance, and background for the project .............................................. 2 1.4 The State of the Art ..................................................................................................... 4 1.5 Methodology ................................................................................................................ 8 1.6 Thesis objectives ........................................................................................................ 10 1.7 Thesis outline ............................................................................................................ -

Alla Zingarese August 5 and 6

Concert Program V: Alla Zingarese August 5 and 6 Friday, August 5 F RANZ JOSEph HAYDN (1732–1809) 8:00 p.m., Stent Family Hall, Menlo School Rondo all’ongarese (Gypsy Rondo) from Piano Trio in G Major, Hob. XV: 25 (1795) S Jon Kimura Parker, piano; Elmar Oliveira, violin; David Finckel, cello Saturday, August 6 8:00 p.m., The Center for Performing Arts at Menlo-Atherton HErmaNN SchULENBURG (1886–1959) AM Puszta-Märchen (Gypsy Romance and Czardas) (1936) PROgram OVERVIEW CharlES ROBERT VALDEZ A lifelong fascination with popular music of all kinds—espe- Serenade du Tzigane (Gypsy Serenade) cially the Gypsy folk music that Hungarian refugees brought to Germany in the 1840s—resulted in some of Brahms’s most ANONYMOUS cap tivating works. The music Brahms composed alla zinga- The Canary rese—in the Gypsy style—constitutes a vital dimension of his Wu Han, piano; Paul Neubauer, viola creative identity. Concert Program V surrounds Brahms’s lusty Hungarian Dances with other examples of compos- JOHANNES BrahmS (1833–1897) PROGR ERT ers drawing from Eastern European folk idioms, including Selected Hungarian Dances, WoO 1, Book 1 (1868–1869) C Hungarian Dance no. 1 in g minor; Hungarian Dance no. 6 in D-flat Major; the famous rondo “in the Gypsy style” from Joseph Haydn’s Hungarian Dance no. 5 in f-sharp minor G Major Piano Trio; the Slavonic Dances of Brahms’s pro- Wu Han, Jon Kimura Parker, piano ON tégé Antonín Dvorˇák; and Maurice Ravel’s Tzigane, a paean C to the Hun garian violin virtuoso Jelly d’Arányi. -

ABSTRACT Final

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE BREADTH OF CHOPIN’S INFLUENCE ON FRENCH AND RUSSIAN PIANO MUSIC OF THE LATE 19TH AND EARLY 20TH CENTURIES Jasmin Lee, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2015 Dissertation directed by: Professor Bradford Gowen School of Music Frederic Chopin’s legacy as a pianist and composer served as inspiration for generations of later composers of piano music, especially in France and Russia. Singing melodies, arpeggiated basses, sensitivity to sonorities, the use of rubato, pedal points, and the full range of the keyboard, plus the frequent use of character pieces as compositional forms characterize Chopin’s compositional style. Future composers Claude Debussy, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Alexander Scriabin, Nikolai Medtner, Gabriel Faure, and Maurice Ravel each paid homage to Chopin and his legacy by incorporating and enhancing aspects of his writing style into their own respective works. Despite the disparate compositional trajectories of each of these composers, Chopin’s influence on the development of their individual styles is clearly present. Such influence served as one of the bases for Romantic virtuoso works that came to predominate the late 19th and early 20th century piano literature. This dissertation was completed by performing selected works of Claude Debussy, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Alexander Scriabin, Gabriel Faure, Nikolai Medtner, and Maurice Ravel, in three recitals at the Gildenhorn Recital Hall in the Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center of the University of Maryland. Compact Disc recordings of the recital are housed -

(MTO 21.1: Stankis, Ravel's ficolor

Volume 21, Number 1, March 2015 Copyright © 2015 Society for Music Theory Maurice Ravel’s “Color Counterpoint” through the Perspective of Japonisme * Jessica E. Stankis NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.15.21.1/mto.15.21.1.stankis.php KEYWORDS: Ravel, texture, color, counterpoint, Japonisme, style japonais, ornament, miniaturism, primary nature, secondary nature ABSTRACT: This article establishes a link between Ravel’s musical textures and the phenomenon of Japonisme. Since the pairing of Ravel and Japonisme is far from obvious, I develop a series of analytical tools that conceptualize an aesthetic orientation called “color counterpoint,” inspired by Ravel’s fascination with Chinese and Japanese art and calligraphy. These tools are then applied to selected textures in Ravel’s “Habanera,” and “Le grillon” (from Histoires naturelles ), and are related to the opening measures of Jeux d’eau and the Sonata for Violin and Cello . Visual and literary Japonisme in France serve as a graphical and historical foundation to illuminate how Ravel’s color counterpoint may have been shaped by East Asian visual imagery. Received August 2014 1. Introduction It’s been given to [Ravel] to bring color back into French music. At first he was taken for an impressionist. For a while he encountered opposition. Not a lot, and not for long. And once he got started, what production! —Léon-Paul Fargue, 1920s (quoted in Beucler 1954 , 53) Don’t you think that it slightly resembles the gardens of Versailles, as well as a Japanese garden? —Ravel describing his Le Belvédère, 1931 (quoted in Orenstein 1990 , 475) In “Japanizing” his garden, Ravel made unusual choices, like his harmonies. -

PROGRAM NOTES by Pamela Dellal (PD) & Michael Manning (MM)

PROGRAM NOTES by Pamela Dellal (PD) & Michael Manning (MM) © 2013 The transition from the 19th to the 20th centuries saw what is arguably history’s greatest revolution in music – indeed, in art. The grandiose ambitions of Romanticism that began with Hector Berlioz had become fully realized in the megalomythic operas of Richard Wagner and the prolix, populous symphonies of Gustav Mahler. Looking through the other end of the telescope, the Romantic miniature that began with Franz Schubert, Felix Mendelssohn, Frederic Chopin, Robert Schumann and Franz Liszt culminated in the technically and psychologically complex and deeply layered songs of Hugo Wolf and the compact, plenipotentiary late works of Johannes Brahms. For younger generations of composers inheriting this auspicious legacy, the glaring question facing them was “now what?”. So began the full assault on aesthetics, politics and culture that would spawn what in retrospect we call modernism. This assault came from multiple schools of thought, from every Western nationality, from every quarter, and its ambition was both focused and comprehensive: dismantle this edifice and start over. In music, the momentum built in two primary places, Germany and France. The former movement saw two principal branches, a very technical one led by Arnold Schoenberg and his disciples, and the very practical one intertwined with the Bauhaus movement and best represented by Paul Hindemith and Kurt Weill. In France, the effort was led by Claude Debussy with the able help of his junior, Maurice Ravel. Together, they embody a style of composition that borrowed its name from painting – Impressionisme, a moniker that was actually despised by both composers who saw it as a lazy term of convenience invented by “imbeciles”, i.e. -

Program Notes Amelia Bailey Distinguished Major Recital March 27Th, 2021 at 3:30Pm

Program Notes Amelia Bailey Distinguished Major Recital March 27th, 2021 at 3:30pm Roma Folk Dances: Villages Tunes of the Hungarian Roma. Daniel Sender (1982-) I. Ha elvettél, tartsá (Öcsöd) II. I canka uj Anna (Püspökladány) III. Hallgató (Mezókovácsháza) for Violin Solo IV. Ének (Püspökladány) V. Jaj, anyám, a vakaró (Csenyéte) Daniel Sender is currently the concertmaster of the Charlottesville Symphony and the Charlottesville Opera, as well as associate violin professor at UVA. Sender studied at Ithaca College, the University of Maryland–where he received his PhD, the Liszt Academy (Budapest) and the Institute for European Studies (Vienna). His scholarship in Hungarian music began when he was awarded a Fulbright Student Scholar grant for his research in Budapest (2010-11), where he attended the Liszt Academy as a student of Vilmos Szabadi and became interested in Hungarian Roma folk music. (Note: unless otherwise stated, assume “Hungary” in terms of folk music geographically refers to the late Austro-Hungarian Empire which existed prior to the Treaty of Trianon. At the end of WWI, the Treaty of Trianon split 75% of Austro-Hungary’s territory up into modern day Romania, Czechoslovakia, Austria, and the Balkans.) The Roma people in Hungary–also known as Romani people, and previously, “gypsies,” though that term is now considered outdated slang, are the largest minority group in Hungary, making up between 3 and 7% of the population. There is a clear cultural divide between those who consider themselves native Hungarians, and Roma people. A large proportion of the Roma population lives in extreme poverty and faces constant racial discrimination, while the European Union and Hungarian officials are only just beginning to take accountability. -

May, 1952 TABLE of CONTENTS

111 AJ( 1 ~ toa TlE PIANO STYI2 OF AAURICE RAVEL THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS by Jack Lundy Roberts, B. I, Fort Worth, Texas May, 1952 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OFLLUSTRTIONS. Chapter I. THE DEVELOPMENT OF PIANO STYLE ... II. RAVEL'S MUSICAL STYLE .. # . , 7 Melody Harmony Rhythm III INFLUENCES ON RAVEL'S EIANO WORKS . 67 APPENDIX . .* . *. * .83 BTBLIO'RAWp . * *.. * . *85 iii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Jeux d'Eau, mm. 1-3 . .0 15 2. Le Paon (Histoires Naturelles), mm. la-3 .r . -* - -* . 16 3. Le Paon (Histoires Naturelles), 3 a. « . a. 17 4. Ondine (Gaspard de a Nuit), m. 1 . .... 18 5. Ondine (Gaspard de la Nuit), m. 90 . 19 6. Sonatine, first movement, nm. 1-3 . 21 7. Sonatine, second movement, 22: 8. Sonatine, third movement, m m . 3 7 -3 8 . ,- . 23 9. Sainte, umi. 23-25 . * * . .. 25 10. Concerto in G, second movement, 25 11. _Asi~e (Shehdrazade ), mm. 6-7 ... 26 12. Menuet (Le Tombeau de Coupe rin), 27 13. Asie (Sh6hlrazade), mm. 18-22 . .. 28 14. Alborada del Gracioso (Miroirs), mm. 43%. * . 8 28 15. Concerto for the Left Hand, mii 2T-b3 . *. 7-. * * * .* . ., . 29 16. Nahandove (Chansons Madecasses), 1.Snat ,-5 . * . .o .t * * * . 30 17. Sonat ine, first movement, mm. 1-3 . 31 iv Figure Page 18. Laideronnette, Imperatrice des l~~e),i.......... Pagodtes (jMa TV . 31 19. Saint, mm. 4-6 « . , . ,. 32 20. Ondine (caspard de la Nuit), in. 67 .. .4 33 21. -

Resource Pack: Ravel

RESOURCE PACK: RAVEL musicbehindthelines.org FOOTER INSERT ACE LOGO RPO LOGO WML LOGO MAURICE RAVEL (1875–1937) RAVEL: FURTHER REFERENCE ABOUT BEHIND THE LINES Books, Scores & Audio BIOGRAPHY Periodicals Ravel during the War Websites Chronology of Key dates WW1 CENTENARY LINKS FEATURED COMPOSITIONS Le tombeau de Couperin La Valse Page | 2a About Behind the Lines Behind the Lines was a year-long programme of free participatory events and resources for all ages to commemorate the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War. The programme was delivered in partnership by Westminster Music Library and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, and supported using public funding by Arts Council England. Public Workshops Beginning in autumn 2013, educational leaders and world-class musicians from the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra led a series of 18 interactive workshops for adults and families (early years and primary age focus). Sessions explored the music and composers of the First World War through these engaging creative composition workshops, targeted at the age group specified, and using the music and resources housed in Westminster Music Library. Schools Projects In addition to the public workshop series, Behind the Lines also worked with six schools in Westminster and the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea; two secondaries and four primaries. These six schools participated in 2 day creative composition projects which drew upon the themes of the programme and linked in with the schools own learning programmes – in particular the History, Music and English curriculum. Additional schools projects can be incorporated in to the Behind the Lines programme between 2014 – 2018, although fundraising will be required. -

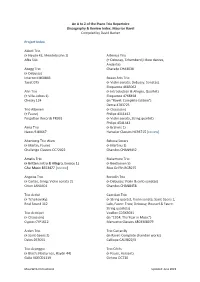

Ravel Compiled by David Barker

An A to Z of the Piano Trio Repertoire Discography & Review Index: Maurice Ravel Compiled by David Barker Project Index Abbot Trio (+ Haydn 43, Mendelssohn 1) Artenius Trio Afka 544 (+ Debussy, Tchemberdji: Bow dances, Andante) Abegg Trio Charade CHA3038 (+ Debussy) Intercord 860866 Beaux Arts Trio Tacet 075 (+ Violin sonata; Debussy: Sonatas) Eloquence 4683062 Ahn Trio (+ Introduction & Allegro, Quartet) (+ Villa-Lobos 1) Eloquence 4768458 Chesky 124 (in “Ravel: Complete Edition”) Decca 4783725 Trio Albeneri (+ Chausson) (+ Faure) Philips 4111412 Forgotten Records FR991 (+ Violin sonata, String quartet) Philips 4541342 Alma Trio (+ Brahms 1) Naxos 9.80667 Hanssler Classics HC93715 [review] Altenberg Trio Wien Bekova Sisters (+ Martin, Faure) (+ Martinu 1) Challenge Classics CC72022 Chandos CHAN9452 Amatis Trio Blakemore Trio (+ Britten: Intro & Allegro, Enescu 1) (+ Beethoven 5) CAvi Music 8553477 [review] Blue Griffin BGR275 Angelus Trio Borodin Trio (+ Cortes, Grieg: Violin sonata 2) (+ Debussy: Violin & cello sonatas) Orion LAN0401 Chandos CHAN8458 Trio Arché Caecilian Trio (+ Tchaikovsky) (+ String quartet, Violin sonata; Saint-Saens 1, Real Sound 112 Lalo, Faure: Trios; Debussy, Roussel & Faure: String quartets) Trio Archipel VoxBox CD3X3031 (+ Chausson) (in “1914: The Year in Music”) Cypres CYP1612 Menuetto Classics 4803308079 Arden Trio Trio Carracilly (+ Saint-Saens 2) (in Ravel: Complete chamber works) Delos DE3055 Calliope CAL3822/3 Trio Arpeggio Trio Cérès (+ Bloch: Nocturnes, Haydn 44) (+ Faure, Hersant) Gallo VDECD1119 Oehms -

The Piano Trio, the Duo Sonata, and the Sonatine As Seen by Brahms, Tchaikovsky, and Ravel

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: REVISITING OLD FORMS: THE PIANO TRIO, THE DUO SONATA, AND THE SONATINE AS SEEN BY BRAHMS, TCHAIKOVSKY, AND RAVEL Hsiang-Ling Hsiao, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2017 Dissertation directed by: Professor Rita Sloan School of Music This performance dissertation explored three significant piano trios, two major instrumental sonatas and a solo piano sonatine over the course of three recitals. Each recital featured the work of either Brahms, Tchaikovsky or Ravel. Each of these three composers had a special reverence for older musical forms and genres. The piano trio originated from various forms of trio ensemble in the Baroque period, which consisted of a dominating keyboard part, an accompanying violin, and an optional cello. By the time Brahms and Tchaikovsky wrote their landmark trios, the form had taken on symphonic effects and proportions. The Ravel Trio, another high point of the genre, written in the early twentieth century, went even further exploring new ways of using all possibilities of each instrument and combining them. The duo repertoire has come equally far: duos featuring a string instrument with piano grew from a humble Baroque form into a multifaceted, flexible classical form. Starting with Bach and continuing with Mozart and Beethoven, the form traveled into the Romantic era and beyond, taking on many new guises and personalities. In Brahms’ two cello sonatas, even though the cello was treated as a soloist, the piano still maintained its traditional prominence. In Ravel’s jazz-influenced violin sonata, he treated the two instruments with equal importance, but worked with their different natures and created an innovative sound combination. -

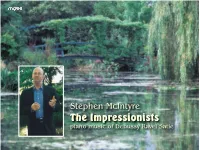

The Impressionists

Stephen McIntyre The Impressionists piano music of Debussy Ravel Satie Claude DEBUSSY (1862-1918) Images (1) 1 Reflets dans l’eau 5’39 2 Hommage à Rameau 7’10 3 Mouvement 3’26 Images (2) 4 Cloches à travers les feuilles 3’54 5 Et la lune descend sur le temple qui fut 4’58 6 Poissons d’or 3’31 Stephen Children’s Corner McIntyre 7 Doctor Gradus ad Parnassum 2’22 8 Jimbo’s Lullaby 3’25 9 Serenade for the Doll 3’09 The q0 The Snow is Dancing 2’42 qa The Little Shepherd 2’25 Impressionists qs Golliwog’s Cakewalk 2’58 Maurice RAVEL (1875-1937) Gaspard de la Nuit (Trois poèmes pour piano d’après Aloysius Bertrand) qd Ondine 6’37 qf Le Gibet 7’15 qg Scarbo 9’36 Erik SATiE (1866-1925) Trois Gnossiennes P 2000 qh Gnossiennes No 1 3’03 MOVE RECORDS qj Gnossiennes No 2 1’46 move.com.au qk Gnossiennes No 3 2’28 Claude Debussy surpassing delicacy and The second set of Images, completed in 1907, are subtlety. Alfred Cortot, both simpler and more complex. Cloches à (1862-1918) one of his principal early travers les feuilles suggests a multiplicity of bells interpreters, described it heard tolling plaintively and thunderously through The importance of the music of as “a new poetry, where the stirring of leaves. Et la lune descend sur le Claude Debussy for the bubbling laughter and temple qui fut sets a tranquil scene of moonlight development of the art in the murmured sighs, heard a over ruined temples, a profound contemplation in 20th century cannot be thousand times in every which harmonic idiom and the uses of the overstated. -

ITALIAN, PORTUGUESE, SPANISH and LATIN AMERICAN SYMPHONIES from the 19Th Century to the Present

ITALIAN, PORTUGUESE, SPANISH AND LATIN AMERICAN SYMPHONIES From the 19th Century to the Present A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman FRANCO ALFANO (1876-1960, ITALY) Born in Posillipo, Naples. After studying the piano privately with Alessandro Longo, and harmony and composition with Camillo de Nardis and Paolo Serrao at the Conservatorio di San Pietro a Majella, Naples, he attended the Leipzig Conservatory where he completed his composition studies with Salomon Jadassohn. He worked all over Europe as a touring pianist before returning to Italy where he eventually settled in San Remo. He held several academic positions: first as a teacher of composition and then director at the Liceo Musicale, Bologna, then as director of the Liceo Musicale (later Conservatory) of Turin and professor of operatic studies at the Conservatorio di San Cecilia, Rome. As a composer, he speacialized in opera but also produced ballets, orchestral, chamber, instrumental and vocal works. He is best known for having completed Puccini’s "Turandot." Symphony No. 1 in E major "Classica" (1908-10) Israel Yinon/Brandenburg State Orchestra, Frankfurt ( + Symphony No. 2) CPO 777080 (2005) Symphony No. 2 in C major (1931-2) Israel Yinon/Brandenburg State Orchestra, Frankfurt ( + Symphony No. 1) CPO 777080 (2005) ANTONIÓ VICTORINO D'ALMEIDA (b.1940, PORTUGAL) Born in Lisbon.. He was a student of Campos Coelho and graduated from the Superior Piano Course of the National Conservatory of Lisbon. He then studied composition with Karl Schiske at the Vienna Academy of Music. He had a successful international career as a concert pianist and has composed prolifically in various genres including: instrumental piano solos, chamber music, symphonic pieces and choral-symphonic music, songs, opera, cinematic and theater scores.