The Concurrent Prevalence of Modernism and Romanticism As Seen in the Operas Performed Between the World Wars and Exemplified in Ernst Krenek’S Jonny Spielt Auf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tocc0298notes.Pdf

ERNST KRENEK AT THE PIANO: AN INTRODUCTION by Peter Tregear Ernst Krenek was born on 23 August 1900 in Vienna, the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and grew up in a house that overlooked the original gravesites of Beethoven and Schubert. His parents hailed from Čáslav, in what was then Bohemia, but had moved to the city when his father, an officer in the commissary corps of the Imperial Austro-Hungarian Army, had received a posting there. Vienna, the self-styled ‘City of Music’, considered itself to be the well-spring of a musical tradition synonymous with the core values of western classical music, and so it was no matter that neither of Krenek’s parents was a practising musician of any stature: Ernst was exposed to music – and lots of it – from a very young age. Later in life he recalled with wonder the fact that ‘walking along the paths that Beethoven had walked, or shopping in the house in which Mozart had written “Don Giovanni”, or going to a movie across the street from where Schubert was born, belonged to the routine experiences of my childhood’.1 As befitting an officer’s son, Krenek received formal musical instruction from a young age, in particular piano lessons and instruction in music theory. The existence of a well-stocked music hire library in the city enabled him to become, by his mid-teens, acquainted with the entire standard Classical and Romantic piano literature of the day. His formal schooling coincidentally introduced Krenek to the literature of classical antiquity and helped ensure that his appreciation of this music would be closely associated in his own mind with his appreciation of western history and classical culture more generally. -

Alla Zingarese August 5 and 6

Concert Program V: Alla Zingarese August 5 and 6 Friday, August 5 F RANZ JOSEph HAYDN (1732–1809) 8:00 p.m., Stent Family Hall, Menlo School Rondo all’ongarese (Gypsy Rondo) from Piano Trio in G Major, Hob. XV: 25 (1795) S Jon Kimura Parker, piano; Elmar Oliveira, violin; David Finckel, cello Saturday, August 6 8:00 p.m., The Center for Performing Arts at Menlo-Atherton HErmaNN SchULENBURG (1886–1959) AM Puszta-Märchen (Gypsy Romance and Czardas) (1936) PROgram OVERVIEW CharlES ROBERT VALDEZ A lifelong fascination with popular music of all kinds—espe- Serenade du Tzigane (Gypsy Serenade) cially the Gypsy folk music that Hungarian refugees brought to Germany in the 1840s—resulted in some of Brahms’s most ANONYMOUS cap tivating works. The music Brahms composed alla zinga- The Canary rese—in the Gypsy style—constitutes a vital dimension of his Wu Han, piano; Paul Neubauer, viola creative identity. Concert Program V surrounds Brahms’s lusty Hungarian Dances with other examples of compos- JOHANNES BrahmS (1833–1897) PROGR ERT ers drawing from Eastern European folk idioms, including Selected Hungarian Dances, WoO 1, Book 1 (1868–1869) C Hungarian Dance no. 1 in g minor; Hungarian Dance no. 6 in D-flat Major; the famous rondo “in the Gypsy style” from Joseph Haydn’s Hungarian Dance no. 5 in f-sharp minor G Major Piano Trio; the Slavonic Dances of Brahms’s pro- Wu Han, Jon Kimura Parker, piano ON tégé Antonín Dvorˇák; and Maurice Ravel’s Tzigane, a paean C to the Hun garian violin virtuoso Jelly d’Arányi. -

Adam Mickiewicz's

Readings - a journal for scholars and readers Volume 1 (2015), Issue 2 Adam Mickiewicz’s “Crimean Sonnets” – a clash of two cultures and a poetic journey into the Romantic self Olga Lenczewska, University of Oxford The paper analyses Adam Mickiewicz’s poetic cycle ‘Crimean Sonnets’ (1826) as one of the most prominent examples of early Romanticism in Poland, setting it across the background of Poland’s troubled history and Mickiewicz’s exile to Russia. I argue that the context in which Mickiewicz created the cycle as well as the final product itself influenced the way in which Polish Romanticism developed and matured. The sonnets show an internal evolution of the subject who learns of his Romantic nature and his artistic vocation through an exploration of a foreign land, therefore accompanying his physical journey with a spiritual one that gradually becomes the main theme of the ‘Crimean Sonnets’. In the first part of the paper I present the philosophy of the European Romanticism, situate it in the Polish historical context, and describe the formal structure of the Crimean cycle. In the second part of the paper I analyse five selected sonnets from the cycle in order to demonstrate the poetic journey of the subject-artist, centred around the epistemological difference between the Classical concept of ‘knowing’ and the Romantic act of ‘exploring’. Introduction The purpose of this essay is to present Adam Mickiewicz's “Crimean Sonnets” cycle – a piece very representative of early Polish Romanticism – in the light of the social and historical events that were crucial for the rise of Romantic literature in Poland, with Mickiewicz as a prize example. -

German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940 Academic attention has focused on America’sinfluence on European stage works, and yet dozens of operettas from Austria and Germany were produced on Broadway and in the West End, and their impact on the musical life of the early twentieth century is undeniable. In this ground-breaking book, Derek B. Scott examines the cultural transfer of operetta from the German stage to Britain and the USA and offers a historical and critical survey of these operettas and their music. In the period 1900–1940, over sixty operettas were produced in the West End, and over seventy on Broadway. A study of these stage works is important for the light they shine on a variety of social topics of the period – from modernity and gender relations to new technology and new media – and these are investigated in the individual chapters. This book is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core at doi.org/10.1017/9781108614306. derek b. scott is Professor of Critical Musicology at the University of Leeds. -

F' ~I!~~ Disc Edition TCO93-75

NEW PUBLICATIONS ARTICLES Block. Geoffrey. 'The Broadway Canon from Show Boat to West Side Story and the European Operatic Ideal." Journal ofMusicology 11, no. 4 (Fall 1993): 525-544. Brooks,Jeanice R. "Nadia Boulanger and the Salon ofthe Princesse de Polignac." Journal ofthe American Musicological Society 46, no. 3 (Fall 1993): 415-468. Dtimling, Albrecht. "Hearing, Speaking, Singing, Writing: The Meaning of Oral Tradi tion for Bert Brecht." In Music and Gennan Literature: Their Relationship Since the Middle Ages, edited by James M. McGiathery, 31~326. Columbia, SC: Camden House, 1992. Krabbe, Niels. "Pris Kulden, M0rket Og Fordrervet: Requiem for 20'ernes Berlin." In Musikken Har Ordet: 36 Musikalske Studier, redigeret af Finn Gravesen, 133-142. Copenhagen: Gads Forlag, 1993. Lipman, Samuel. ''Wby Kurt Weill?" In Music and More: Essays, 1975-1991. By Samuel Lipman, 3~49. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1992. Margry, Karel. "'Theresienstadt' (1944-1945):The Nazi Propaganda Film Depicting the Concentration Camp as Paradise." Historical Journal ofFilm, Radio and Television 12, no. 2 (1992): 145-162. [A Gennan version appeared in: Kamy, Miroslav, ed. 11ieresienstadt: Jn der "Endlosung der Judenfrage." Prag: Panorama, 1992.) Schebera, Ji.irgen. '"Meine Tage in Dessau sind gezahlt .. .': Kurt Weill in Briefen aus seiner Vaterstadt." Dessauer Ka/ender 37 (1993): 18-24. Taruskin, Richard. 'The Golden Age ofKitsch: The Seductions and Betrayals ofWeimar Opera." The New Republic (21 March 1994): 28-36. BOOKS Green, Paul. A Southern life: Letters ofPaul Green: 1916-1981. Edited by Laurence G. Avery. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1994. Murphy, Donna B. and Stephen Moore. Helen Hayes: A Bio-Bibliography. -

Liner Notes, Visit Our Web Site: Recording: March 22, 2012, Philharmonie in Berlin, Germany

21802.booklet.16.aas 5/23/18 1:44 PM Page 2 CHRISTIAN WOLFF station Südwestfunk for Donaueschinger Musiktage 1998, and first performed on October 16, 1998 by the SWF Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Jürg Wyttenbach, 2 Orchestra Pieces with Robyn Schulkowsky as solo percussionist. mong the many developments that have transformed the Western Wolff had the idea that the second part could have the character of a sort classical orchestra over the last 100 years or so, two major of percussion concerto for Schulkowsky, a longstanding colleague and friend with tendencies may be identified: whom he had already worked closely, and in whose musicality, breadth of interests, experience, and virtuosity he has found great inspiration. He saw the introduction of 1—the expansion of the orchestra to include a wide range of a solo percussion part as a fitting way of paying tribute to the memory of David instruments and sound sources from outside and beyond the Tudor, whose pre-eminent pianistic skill, inventiveness, and creativity had exercised A19th-century classical tradition, in particular the greatly extended use of pitched such a crucial influence on the development of many of his earlier compositions. and unpitched percussion. The first part of John, David, as Wolff describes it, was composed by 2—the discovery and invention of new groupings and relationships within the combining and juxtaposing a number of “songs,” each of which is made up of a orchestra, through the reordering, realignment, and spatial distribution of its specified number of sounds: originally between 1 and 80 (with reference to traditional instrumental resources. -

Krenek Ernest

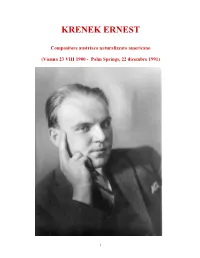

KRENEK ERNEST Compositore austriaco naturalizzato americano (Vienna 23 VIII 1900 - Palm Springs, 22 dicembre 1991) 1 Allievo dal 1916 al 1920 di F. Schreker all'Accademia musicale di Vienna, passò poi alla Hochschule fur Musik di Berlino, dove continuò gli studi con Schreker, ed entrò in proficuo contatto di lavoro con Busoni, A. Schnabel ed altri esponenti del mondo musicale della capitale tedesca. Sposata la figlia di Mahler, Anna (1923) si stabilì in Svizzera ma due anni dopo divorziò e dal 1925 al 1927, su invito di P. Bekker, fu nominato consigliere artistico dell'Opera di Kassel, mettendosi in luce con numerose composizioni teatrali e strumentali ed iniziando un'intensa attività pubblicistica come collaboratore musicale della "Frankfurter Zeitung" e dal 1933 della "Wiener Zeitung”. Ottenuto un successo di portata internazionale con l'opera Jonny spielt auf, dal 1928 si stabilì a Vienna dedicandosi quasi esclusivamente alla composizione, anche qui a contatto con gli ambienti artistici d'avanguardia (Berg, Webern, K. Kraus). Nel 1937 emigrò in America, dove nel 1939 ottenne una cattedra nel Vassar College di Poughkeepsie, presso New York. Dal 1945 ha avuto la cittadinanza americana. Dal 1942 al 1947 ha insegnato nell'Università di Saint Paul, stabilendosi poi a Los Angeles. Dopo la guerra rientrò spesso in Europa, per corsi di composizione, conferenze e concerti. Musicista assai sensibile ai più attuali problemi estetici e di linguaggio, il suo arco creativo rispecchia l'evoluzione spesso contraddittoria delle correnti dell'avanguardia musicale del secolo. L'insegnamento di Schreker lo ha avvicinato nella prima gioventù ad una sorta di espressionismo temperato in senso tardo-romantico, ma ben presto si liberò da quell'influenza per avvicinarsi alle più diverse esperienze musicali. -

Franz A. Birgel Muhlenberg College

Werner Herzog's Debt to Georg Buchner Franz A. Birgel Muhlenberg College The filmmaker Wemcr Herzog has been labeled eve1)1hing from a romantic, visionary idealist and seeker of transcendence to a reactionary. regressive fatalist and t)Tannical megalomaniac. Regardless of where viewers may place him within these e:-..1reme positions of the spectrum, they will presumably all admit that Herzog personifies the true auteur, a director whose unmistakable style and wor1dvie\v are recognizable in every one of his films, not to mention his being a filmmaker whose art and projected self-image merge to become one and the same. He has often asserted that film is the art of i1literates and should not be a subject of scholarly analysis: "People should look straight at a film. That's the only \vay to see one. Film is not the art of scholars, but of illiterates. And film culture is not analvsis, it is agitation of the mind. Movies come from the count!)' fair and circus, not from art and academicism" (Greenberg 174). Herzog wants his ideal viewers to be both mesmerized by his visual images and seduced into seeing reality through his eyes. In spite of his reference to fairgrounds as the source of filmmaking and his repeated claims that his ·work has its source in images, it became immediately transparent already after the release of his first feature film that literature played an important role in the development of his films, a fact which he usually downplays or effaces. Given Herzog's fascination with the extremes and mysteries of the human condition as well as his penchant for depicting outsiders and eccentrics, it comes as no surprise that he found a kindred spirit in Georg Buchner whom he has called "probably the most ingenious writer for the stage that we ever had" (Walsh 11). -

Carpeta QL69-3-2018 FINAL Parte 1.Indb 9 30/05/2019 10:48:12 VICENT MINGUET

LAS REGLAS DE LA MÚSICA Y LAS LEYES DEL ESTADO: LA ENTARTETE MUSIK Y EL TERCER REICH THE RULES OF MUSIC AND THE STATE’S LAWS: ENTARTETE MUSIK AND THE THIRD REICH Vicent Minguet• Debemos cuidarnos de introducir un nuevo estilo de música, ya que nos pondríamos en peligro; pues tal como dice Damón, y yo igualmente estoy convencido de ello, en ningún sitio se cambian las reglas de la música sin que se cambien también las principales leyes del estado. Ahí es donde, según parece, deben establecer su cuerpo de guardia los guardianes. Ahí es, en efecto, donde, al insinuarse, la ilegalidad pasa más fácilmente inadvertida. Platón, República IV, 424. RESUMEN La idea de una Entartete Musik (Música degenerada) se originó en la Alemania del Tercer Reich entre 1937 y 1938 como concepto paralelo al de Entartete Kunst (Arte degenerado), que permitía diferenciar claramente entre un arte alemán “bueno” o puro, y otro “degenerado” que fue prohibido por el Estado. Con el objeto de aclarar los orígenes y las mentalidades que dieron lugar a esta distinción, en el presente artículo examinamos el contexto cultural en que se desenvolvió la maquinaria política, legislativa y burocrática del gobierno nazi. El resultado pone de manifiesto una clara motivación racial: un antisemitismo que en el terreno artístico se remonta al siglo XIX. Palabras Clave: Música degenerada; Arte degenerado; Tercer Reich; Antisemitismo. • Vicent Minguet es músico y musicólogo. Doctor por la Universidad de Valencia con una tesis sobre la significación de la obra de Olivier Messiaen, Master of Arts por la Universidad de Fráncfort y por la Escuela Superior de Música de Basilea. -

Kurt Weill Newsletter Protagonist •T• Zar •T• Santa

KURT WEILL NEWSLETTER Volume 11, Number 1 Spring 1993 IN THI S ISSUE I ssues IN THE GERMAN R ECEPTION OF W EILL 7 Stephen Hinton S PECIAL FEATURE: PROTAGON IST AND Z AR AT SANTA F E 10 Director's Notes by Jonathan Eaton Costume Designs by Robert Perdziola "Der Protagonist: To Be or Not to Be with Der Zar" by Gunther Diehl B OOKS 16 The New Grove Dictionary of Opera Andrew Porter Michael Kater's Different Drummers: Jazz in the Culture of Nazi Germany Susan C. Cook Jilrgen Schebera's Gustav Brecher und die Leipziger Oper 1923-1933 Christopher Hailey PERFORMANCES 19 Britten/Weill Festival in Aldeburgh Patrick O'Connor Seven Deadly Sins at the Los Angeles Philharmonic Paul Young Mahagonny in Karlsruhe Andreas Hauff Knickerbocker Holiday in Evanston. IL bntce d. mcclimg "Nanna's Lied" by the San Francisco Ballet Paul Moor Seven Deadly Sins at the Utah Symphony Bryce Rytting R ECORDINGS 24 Symphonies nos. 1 & 2 on Philips James M. Keller Ofrahs Lieder and other songs on Koch David Hamilton Sieben Stucke aus dem Dreigroschenoper, arr. by Stefan Frenkel on Gallo Pascal Huynh C OLUMNS Letters to the Editor 5 Around the World: A New Beginning in Dessau 6 1993 Grant Awards 4 Above: Georg Kaiser looks down at Weill posing for his picture on the 1928 Leipzig New Publications 15 Opera set for Der Zar /iisst sich pltotographieren, surrounded by the two Angeles: Selected Performances 27 Ilse Koegel 0efl) and Maria Janowska (right). Below: The Czar and His Attendants, costume design for t.he Santa Fe Opera by Robert Perdziola. -

Joseph Beuys and the Reincarnation of German Romanticism

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work Spring 5-2003 Postwar Landscapes: Joseph Beuys and the Reincarnation of German Romanticism Lauren Elizabeth Smith University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Smith, Lauren Elizabeth, "Postwar Landscapes: Joseph Beuys and the Reincarnation of German Romanticism" (2003). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/601 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ----------------~~------~--------------------- Postwar Landscapes: Joseph Beuys and the Reincarnation of German Romanticism Lauren E. Smith College Scholars Senior Thesis University of Tennessee May 1,2003 Dr. Dorothy Habel, Dr. Tim Hiles, and Dr. Peter Hoyng, presiding committee Contents I. Introduction 3 II. Beuys' Germany: The 'Inability to Mourn' 3 III. Showman, Shaman, or Postwar Savoir? 5 IV. Beuys and Romanticism: Similia similibus curantur 9 V. Romanticism in Action: Celtic (Kinloch Rannoch) 12 VI. Celtic+ ---: Germany's symbolic salvation in Basel 22 VII. Conclusion 27 Notes Bibliography Figures Germany, 1952 o Germany, you're torn asunder And not just from within! Abandoned in cold and darkness The one leaves the other alone. And you've got such lovely valleys And plenty of thriving towns; If only you'd trust yourself now, Then all would be just fine. -

William Kentridge Brings 'Wozzeck' Into the Trenches

William Kentridge Brings ‘Wozzeck’ Into the Trenches The artist’s production of Berg’s brutal opera, updated to World War I, has come to the Metropolitan Opera. By Jason Farago (December 26, 2019) ”Credit...Devin Yalkin for The New York Times Three years ago, on a trip to Johannesburg, I had the chance to watch the artist William Kentridge working on a new production of Alban Berg’s knifelike opera “Wozzeck.” With a troupe of South African performers, Mr. Kentridge blocked out scenes from this bleak tale of a soldier driven to madness and murder — whose setting he was updating to the years around World War I, when it was written, through the hand-drawn animations and low-tech costumes that Metropolitan Opera audiences have seen in his stagings of Berg’s “Lulu” and Shostakovich’s “The Nose.” Some of what I saw in Mr. Kentridge’s studio has survived in “Wozzeck,” which opens at the Met on Friday. But he often works on multiple projects at once, and much of the material instead ended up in “The Head and the Load,” a historical pageant about the impact of World War I in Africa, which New York audiences saw last year at the Park Avenue Armory. Mr. Kentridge’s “Wozzeck” premiered at the Salzburg Festival in 2017. Zachary Woolfe of The New York Times called it “his most elegant and powerful operatic treatment yet.” At the Met, the Swedish baritone Peter Mattei will sing the title role for the first time; Elza van den Heever, like Mr. Kentridge from Johannesburg, plays his common-law wife, Marie; and Yannick Nézet- Séguin, the company’s music director, will conduct.