Tocc0298notes.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kurt Weill Newsletter Protagonist •T• Zar •T• Santa

KURT WEILL NEWSLETTER Volume 11, Number 1 Spring 1993 IN THI S ISSUE I ssues IN THE GERMAN R ECEPTION OF W EILL 7 Stephen Hinton S PECIAL FEATURE: PROTAGON IST AND Z AR AT SANTA F E 10 Director's Notes by Jonathan Eaton Costume Designs by Robert Perdziola "Der Protagonist: To Be or Not to Be with Der Zar" by Gunther Diehl B OOKS 16 The New Grove Dictionary of Opera Andrew Porter Michael Kater's Different Drummers: Jazz in the Culture of Nazi Germany Susan C. Cook Jilrgen Schebera's Gustav Brecher und die Leipziger Oper 1923-1933 Christopher Hailey PERFORMANCES 19 Britten/Weill Festival in Aldeburgh Patrick O'Connor Seven Deadly Sins at the Los Angeles Philharmonic Paul Young Mahagonny in Karlsruhe Andreas Hauff Knickerbocker Holiday in Evanston. IL bntce d. mcclimg "Nanna's Lied" by the San Francisco Ballet Paul Moor Seven Deadly Sins at the Utah Symphony Bryce Rytting R ECORDINGS 24 Symphonies nos. 1 & 2 on Philips James M. Keller Ofrahs Lieder and other songs on Koch David Hamilton Sieben Stucke aus dem Dreigroschenoper, arr. by Stefan Frenkel on Gallo Pascal Huynh C OLUMNS Letters to the Editor 5 Around the World: A New Beginning in Dessau 6 1993 Grant Awards 4 Above: Georg Kaiser looks down at Weill posing for his picture on the 1928 Leipzig New Publications 15 Opera set for Der Zar /iisst sich pltotographieren, surrounded by the two Angeles: Selected Performances 27 Ilse Koegel 0efl) and Maria Janowska (right). Below: The Czar and His Attendants, costume design for t.he Santa Fe Opera by Robert Perdziola. -

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Phyllis Curtin - Box 1 Folder# Title: Photographs Folder# F3 Clothes by Worth of Paris (1900) Brooklyn Academy F3 F4 P.C. recording F4 F7 P. C. concert version Rosenkavalier Philadelphia F7 FS P.C. with Russell Stanger· FS F9 P.C. with Robert Shaw F9 FIO P.C. with Ned Rorem Fl0 F11 P.C. with Gerald Moore Fl I F12 P.C. with Andre Kostelanetz (Promenade Concerts) F12 F13 P.C. with Carlylse Floyd F13 F14 P.C. with Family (photo of Cooke photographing Phyllis) FI4 FIS P.C. with Ryan Edwards (Pianist) FIS F16 P.C. with Aaron Copland (televised from P.C. 's home - Dickinson Songs) F16 F17 P.C. with Leonard Bernstein Fl 7 F18 Concert rehearsals Fl8 FIS - Gunther Schuller Fl 8 FIS -Leontyne Price in Vienna FIS F18 -others F18 F19 P.C. with hairdresser Nina Lawson (good backstage photo) FI9 F20 P.C. with Darius Milhaud F20 F21 P.C. with Composers & Conductors F21 F21 -Eugene Ormandy F21 F21 -Benjamin Britten - Premiere War Requiem F2I F22 P.C. at White House (Fords) F22 F23 P.C. teaching (Yale) F23 F25 P.C. in Tel Aviv and U.N. F25 F26 P. C. teaching (Tanglewood) F26 F27 P. C. in Sydney, Australia - Construction of Opera House F27 F2S P.C. in Ipswich in Rehearsal (Castle Hill?) F2S F28 -P.C. in Hamburg (large photo) F2S F30 P.C. in Hamburg (Strauss I00th anniversary) F30 F31 P. C. in Munich - German TV F31 F32 P.C. -

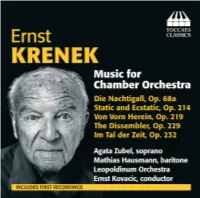

Toccata Classics TOCC 0125 Notes

P ERNEST KRENEK: MUSIC FOR CHAMBER ORCHESTRA by Peter Tregear The Austrian-born composer Ernst Krenek (1900–91) has been described, with good reason, as a compositional ‘companion of the twentieth century’.1 Stretching over seventy years of productive life, his musical legacy encompasses most of the common forms of modern western art music, from string quartets and symphonies to opera and electronic music. Moreover, it engages with many of the key artistic movements of the day – from late Romanticism and Neo- classicism to abstract Expressionism and Post-modernism. The sheer scope of his music seems to reflect something profound about the condition of his turbulent times. The origins of Krenek’s extraordinary artistic disposition are to be found in the equally extraordinary circumstances into which he was born. He came to maturity in Vienna in the dying days of the First World War and the Austro-Hungarian Empire and, with its collapse in 1919, the cultural norms that had nurtured Vienna’s enviable musical reputation all but disappeared. In addition, by this time, new forms of transmission of mass culture, such as the wireless, gramophone and cinema, were transforming the ways and means by which cultural life could be both propagated and received. As an artist trying to come to terms with these changes, Krenek was doubly fortunate. Not only was he generally recognised as one of the most gifted composers of his generation; he was also an insightful thinker about music and its role in society. Right from the moment in 1921 when, in the face of growing tension between himself and his composition teacher Franz Schreker, he set out on a full-time career as a composer, he determined that he would be more than just as a passive reflector of the world around him; he would be both its witness and conscience. -

The Concurrent Prevalence of Modernism and Romanticism As Seen in the Operas Performed Between the World Wars and Exemplified in Ernst Krenek’S Jonny Spielt Auf

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 6-10-2020 The Concurrent Prevalence of Modernism and Romanticism as seen in the Operas Performed between the World Wars and Exemplified in Ernst Krenek’s Jonny Spielt Auf Nicole Fassold Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Fassold, Nicole, "The Concurrent Prevalence of Modernism and Romanticism as seen in the Operas Performed between the World Wars and Exemplified in Ernst Krenek’s Jonny Spielt Auf" (2020). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 5301. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/5301 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE CONCURRENT PREVALENCE OF MODERNISM AND ROMANTICISM AS SEEN IN THE OPERAS PERFORMED BETWEEN THE WORLD WARS AND EXEMPLIFIED IN ERNST KRENEK’S JONNY SPIELT AUF A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The College of Music and Dramatic Arts by Nicole Fassold B.M., Colorado State University, 2015 M.M., University of Delaware, 2017 August 2020 Acknowledgements I would like to express my deepest gratitude to the professors and panel members that have guided me throughout my Doctoral studies as well as to my parents and sister, my family all over the world, my friends, and my incredible husband for their unending support and encouragement. -

John Stewart Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8qj7jg3 No online items John Stewart Papers Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Copyright 2013 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla 92093-0175 [email protected] URL: http://libraries.ucsd.edu/collections/sca/index.html John Stewart Papers MSS 0614 1 Descriptive Summary Languages: English Contributing Institution: Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla 92093-0175 Title: John Stewart Papers Identifier/Call Number: MSS 0614 Physical Description: 5.6 Linear feet(15 archives boxes) Date (inclusive): 1916-1991 Abstract: The papers of John Stewart, author, musician and UCSD Muir College provost (1965-1987) contain the research materials for his book about composer Ernst Krenek titled Ernst Krenek: The Man and His Music (1991), including typescript drafts; notes describing correspondence, essays, and articles about Krenek; chronologies; and a series of reel-to-reel audiorecordings of interviews with Krenek by Stewart. Also included are drafts of writings, teaching materials, and correspondence with colleagues including Ernst Krenek. Biography John Lincoln Stewart was born January 24, 1917 in Alton, Illinois, and grew up in Granville and Dwight, Ontario. He graduated from Dennison College with a double major in English and Music and received his doctorate in English literature at Ohio State University. He served in World War II in the Army Signal Corps. He taught English at UCLA and Dartmouth before joining UCSD, publishing The Burden of Time: The Fugitives and Agrarians, a history of the Nashville literary groups of the 1920s and 1930s. Stewart came to UCSD in 1964 to take the lead in establishing arts departments on campus. -

N E W S L E T T E R Vol

Harvard University Department of MUSICn e w s l e t t e r Vol. 8, No. 2/Summer 2008 The More Things Change...: Music at Harvard, Then & Now Music Building by Anne C. Shreffler North Yard Harvard University Taking advantage of the Cambridge, MA 02138 comparatively quiet sum- mer months, I recently re-read Eliot Forbes’s A 617-495-2791 History of Music at Harvard www.music.fas.harvard.edu to 1972 (Department of Music, Harvard Univer- sity, 1988). Forbes, class of 1941 and a professor in the Music Department INSIDE from 1958 to 1984, known primarily for his magiste- Graduate student Meredith Schweig, Professors Rehding and Shreffler, graduate student 3 Faculty News rial revised and expanded Andrea Bohlman, and Professor Revuluri 4 Tutschku receives tenure; edition of Alexander Wheelock Thayer’s Life of that the musical transaction goes both ways: people Clark appointed Beethoven, writes of the different roles played by can do things with music—perform, compose, and music at Harvard: study it—but music also does things to (and with) 4 RISM adds Yale, Juilliard Music can provide stimulation, often of a deep, us: by providing “stimulation, often of a deep, spiri- manuscripts spiritual nature, to those who perform; music can tual nature...; music can be a life of its own...; music 5 Graduate Student News be a life of its own for those who create it through can be a subject of total absorption.” Finally, Forbes speaks of the special role of music at a liberal arts 6 Library News composition; and music can be a subject of total absorption for those who would study its history university, which must address the needs of those 6 Archiving Ulysses Kay and its roots. -

From Kotoński to Duchnowski. Polish Electroacoustic Music

MIECZYSŁAW KOMINEK (Warszawa) From Kotoński to Duchnowski. Polish electroacoustic music ABSTRACT: Founded in November 1957, the Experimental Studio of Polish Radio (SEPR) was the fifth electronic music studio in Europe and the seventh in the world. It was an extraordinary phenomenon in the reality of the People’s Poland of those times, equally exceptional as the Warsaw Autumn International Festival of Contemporary Music, established around the same time - in 1956. Both these ‘institutions’ would be of fundamental significance for contemporary Polish music, and they would collabo rate closely with one another. But the history of Polish electroacoustic music would to a large extent be the history of the Experimental Studio. The first autonomous work for tape in Poland was Włodzimierz Kotoñski’s Etiuda konkretna (na jedno uderzenie w talerz) [Concrete study (for a single strike of a cymbal)], completed in November 1958. It was performed at the Warsaw Autumn in i960, and from then on electroacoustic music was a fixture at the festival, even a marker of the festival’s ‘modernity’, up to 2002 - the year when the last special ‘con cert of electroacoustic music’ appeared on the programme. In 2004, the SEPR ceased its activities, but thanks to computers, every composer can now have a studio at home. There are also thriving electroacoustic studios at music academies, with the Wroclaw studio to the fore, founded in 1998 by Stanisław Krupowicz, the leading light of which became Cezary Duchnowski. Also established in Wroclaw, in 2005, was the biennial International Festival of Electroacoustic Music ‘Música Electrónica Nova’. KEYWORDS: electroacoustic music, electronic music, concrete music, music for tape, generators, experimental Studio of Polish Radio, “Warsaw Autumn” International Festival of Contemporary Music, live electronic, synthesisers, computer music The beginnings of electroacoustic music can be sought in works scored for, or including, electric instruments. -

TEMPO Periodicals DAS ORCHESTER

98 TEMPO TRADITIONS OF THE CLASSICAL GUITAR by MUSICA Graham Wade. John Calder, £I2-JO. March-April 1980 Ernst Krenek 80th Birthday issue. Claudia BENJAMIN BRITTEN: Pictures from a life 1913- Maurer Zenk, Ernst Krenek—Wandiungen der 1976 compiled by Donald Mitchell and John neuen Musik, pp.n8-i2j. Wolfgang Rihm, Evans. Faber (paperback edition), £4"9J. Bruchstiicke zu: Wandiungen neuer Musik, p. 126. Walter Gieseler, 'Was an der Zeit ist . .', A YOUNG PERSON'S GUIDE TO THE OPERA by pp.127-131. Wolfgang Molkow, Der Sprung Helen Erickson. Macdonald & Jane's, £4*9^ iiber den Schatten, pp. 13 2-13j. John L. Stewart, Frauen in den Opern Ernst Kreneks, A YOUNG PERSON'S GUIDE TO THE BALLET pp.136-138. Gottfried Eberle, Klangkomplex, by Craig Dodd. Macdonald & Jane's, £4-95. Trope, Reihe, pp. 139-147. SOLFEGE, EAR TRAINING, RHYTHM, DIC- MUSICAL QUARTERLY TATION, AND MUSIC THEORY: a Comprehen- Vol.LXVI, No.2 April 1980 sive Course by Marta Arkossy Ghezzo. Uni- Stuart Feder, 'Decoration Day': a Boyhood versity of Alabama Press, £13-0$ Memory of Charles lves, pp. 234-261. Jack Gottlieb, Symbols of Faith in the Music of JOHN TAVERNER: Tudor Composer by David Leonard Bernstein, pp.287-29$. Josephson. University Microfilms Inter- nationa] (Bowker Publishing Company). PERSPECTIVES OF NEW MUSIC Spring - Summer 1979 ZUBIN MEHTA by Martin Bookspan and Ross Claudio Spies, Verscheiden (A Lament for Sey- Yockey. Robert Hale, £7-95 mour Shifrin), pp. 2-9 (composition). Milton Babbitt, Ben Weber (1919-1979), pp.11-13. THE CROSBY YEARS by Ken Barnes. Elm Michela Mollia, 'From Silence towards a New Tree Books. -

Structural Analysis Through Ordered Harmony Transformations in the Early Works of Arnold Schoenberg

Structural Analysis Through Ordered Harmony Transformations in the Early Works of Arnold Schoenberg D.M.A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Blake Ross Henson, B.M., M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2010 Document Committee: Dr. Thomas Wells, Advisor Dr. Gregory Proctor Dr. Jan Radzynski Copyright by Blake Ross Henson 2010 Abstract Arnold Schoenberg’s early period (1894 - 1907) is traditionally considered “Romantic” and discussed alongside late nineteenth century composers such as Hugo Wölf and Alexander Scriabin, despite its consistently challenging the limits of tonality. Because the music in Schoenberg’s second period (1908 - 1922) is generally described as “freely atonal,” a prelude to his dodecaphonic system, this first period is often discussed similarly as “atonal” or “pre-atonal.” As a consequence, a repertoire of early Schoenberg works slip through the analytic cracks for being “too chromatic” for nineteenth century analysts and “too tonal” for theorist of atonal and serial works. Although music in his later period is indeed non-tonal, I believe Schoenberg’s early works to be an extension of chromatic tonality that is colored by the possibility of its becoming, not dependent upon it. This belief stems from the music in question’s many gestures that quite simply sound tonal but may not be functional (that is, a sonority may be aurally understood as a dominant seventh although it may not resolve in a manner proceeding by tonal expectations), as well as the abundance of triads that regularly permeate the music in this period. -

Ernst Křenek's Second Piano Sonata the Embodiment of His Stabilization

Ernst Křenek’s Second Piano Sonata The Embodiment of his Stabilization Period by Andrew Ramos B.M., University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, 2013 M.M., University of Colorado at Boulder, 2015 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Musical Arts College of Music 2018 Abstract Ramos, Andrew (D.M.A., College of Music) Ernst Křenek’s Second Piano Sonata: The Embodiment of his Stabilization Period Thesis directed by Dr. Andrew Cooperstock Ernst Křenek (1900-1991) was an Austrian composer. He resided in various places throughout Europe, until he emigrated to the United States in 1938. In the U.S., he taught and lectured at various universities. Today, he is remembered for his association with The Second Viennese School. Krenek is also known for his completion of Schubert’s Reliquie piano sonata and his editing of movements of Mahler’s 10th symphony. Krenek’s views on music changed throughout his life. His long lifespan exposed him to a variety of musical perspectives. He grappled with ideas such as music’s function or “appropriate” aesthetics; at times he contradicted his own previously held beliefs. Krenek believed “systems come and systems go; since none is inherent in the material, composers select whatever system is needed to solve the problems presented by their expressive aims.”1 In the 1920s, Krenek had three stylistic shifts. From 1916 to 1921, he studied with Franz Schreker, a famous opera composer and teacher. Krenek’s music from this period used late- Romantic harmonic language. -

ARSC Journal

HISTORICAL REISSUES SCHUBERT: Die schone Miillerin; Winterreise; Schwanengesang. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Gerald Moore, piano. EMI 127-01764/66, 3 discs. Returning to the first Fischer-Dieskau-Moore Schubert cycle record ings, I have tried to turn back the clock and listen without reference to their long list of later performances. My first impression of Fischer-Dieskau was from the old Fritz Lehmann Saint Matthew Passion recording, in which he sang the Christus. I was enough impressed to become an avid collector of his recordings until they became too numerous for me. My first opportunity to hear him in the flesh was in Edinburgh in 1953, when he and Moore gave a Beethoven recital. Needless to say, I was present at his New York debut, Winterreise sung without interruption and without encores. Few singers of any period have been able to hold an audience so spellbound. It was in this frame of mind that I first heard this recording of Die schone Mullerin. The date of recording is given on the container - 3 and 7 October 1951. At 26 Fischer-Dieskau was already well established as a lieder singer of the first rank. We do not know how much time and study had gone into these songs, but presumably he felt he had arrived at his definitive interpretation. The records reveal a fresh young voice and a thoughtful approach. He presents a gentle apprentice miller, self centered and reserved, vigorous and unsophisticated. I like the jaunti ness of Das Wandern and the way both fischer-Dieskau and Moore make the contrasts among the stanzas without jarring the musical line. -

Così Fan Tutte at Seattle Opera

mozart COSÌ FAN TUTTE B:8.625” T:8.375” S:7.375” C M Y K BELLEVUE SQUARE T:10.875” S:9.875” B:11.125” COME TOGETHER EAP full-page template.indd 1 11/10/17 11:53 AM 309485bar01_SeattleSymphy df PUBLICATION BACK COVER UNIT/SIZE PAGE INSERTION DATE 12.03 DOCUMENT NAME: BRSP17DE_ADV_SEATTLESYMPHONY_AD.INDD PRODUCTION ARTIST: PIERXE LUONG FILE PATH: ...NTOSH HD:USERS:PI17943:BOX SYNC:PIERXES_PROJECTS:ADVERTISING:BRSP17DE_ADV_SEATTLESYMPHONY_AD.INDD DESIGNER: SARASVATI MUNOZ BLEED: 8.625” X 11.125” LASER SCALE: NONE COPY/PROOF READ: STEPHANIE DAVILA TRIM: 8.375” X 10.875” LAST MODIFED: 11-6-2017 5:21 PM ACCOUNT MANAGER: DAVID PRETZOLD LIVE: 7.375” X 9.875” MODIFED BY: PIERXE LUONG PRINT PRODUCTION: MARY AGRESTA GUTTER: NONE DUE TO PUB: NONE PROJECT MANAGER: STEPHANIE MONRAD SCALE: 100% IMAGE CODE: 17HO461_17_75260009_R4_QC.TIF FONTS: FUTURA LT BT (LIGHT), TFARROWMEDIUM (REGULAR) COLORS: CYAN DIE LINE/NOTES MAGENTA YELLOW BLACK PACIFIC DIGITAL IMAGE • 333 Broadway, San Francisco CA 94133 • 415.274.7234 • www.pacdigital.com Filename: 309485bar01_SeattleSymphy.pdf_w Operator:SpoolServer Time:15:13:15 Colors: Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, Black Date:17-11-08 NOTE TO RECIPIENT: This file is processed using a Prinergy Workflow System with an Adobe Postscript Level 3 RIP. The resultant PDF contains traps and overprints. Please ensure that any post-processing used to produce these files supports this functionality. To correctly view these files in Acrobat, please ensure that Output Preview (Separation Preview in earlier versions than 7.x) and Overprint Preview are enabled. If the files are re-processed and these aspects are ignored, the traps and/or overprints may not be interpreted correctly and incorrect reproduction may result.