Toccata Classics TOCC 0125 Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Einem Gottfried

EINEM VON GOTTFRIED Compositore austriaco (Berna 24 I 1918 - Waldviertel 12 VII 1966) Dapprima autodidatta, Gottfried von Einem studiò con Boris Blacher e sviluppò in seguito un equilibrato linguaggio musicale. Nel 1938 iniziò la sua carriera come istruttore di canto all'Opera di Berlino e come assistente al Festival di Bayreuth. Durante il nazionalsocialismo venne più volte arrestato. Dopo la guerra Einem rivestì varie funzioni sia al Festival di Salisburgo, sia alle Festwochen di Vienna. Dal 1963 al 1972 insegnò alla Musikhochschule di Vienna, dal 1964 fu membro della Akademie der Kunste di Berlino e dal 1965 al 1970 presidente dell'Akademie fur Musik austriaca. 1 DANTONS TOD Di Gottfried von Einem (1918-1996) libretto proprio e di Boris Blacher, dal dramma di Georg Büchner (La morte di Danton) Opera in due atti e sei quadri Prima: Salisburgo, Felsenreitschule, 6 agosto 1947 Personaggi: Georges Danton (Bar); Julie, sua moglie (Ms); Camille Desmoulins e Jean Hérault de Séchelles, deputati (T); Lucille, moglie di Camille (S); Maximilien Robespierre (T); Saint-Just (B); Simon, suggeritore (B); due becchini (T); una dama (S); una popolana (A); uomini e donne del popolo In Dantons Tod non si saluta solo un esordio teatrale particolarmente felice, tanto da decretare all’autore fama subitanea, ma anche l’inizio della consuetudine salisburghese (mai più abbandonata) di inserire ogni anno nel Festival un’opera contemporanea in ‘prima’ assoluta. Il soggetto di Büchner venne scelto sull’onda emotiva suscitata dal fallito attentato a Hitler nel 1944; ad approntare la versione ridotta fu Boris Blacher, maestro di Einem e futuro dedicatario dell’opera. -

Tocc0298notes.Pdf

ERNST KRENEK AT THE PIANO: AN INTRODUCTION by Peter Tregear Ernst Krenek was born on 23 August 1900 in Vienna, the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and grew up in a house that overlooked the original gravesites of Beethoven and Schubert. His parents hailed from Čáslav, in what was then Bohemia, but had moved to the city when his father, an officer in the commissary corps of the Imperial Austro-Hungarian Army, had received a posting there. Vienna, the self-styled ‘City of Music’, considered itself to be the well-spring of a musical tradition synonymous with the core values of western classical music, and so it was no matter that neither of Krenek’s parents was a practising musician of any stature: Ernst was exposed to music – and lots of it – from a very young age. Later in life he recalled with wonder the fact that ‘walking along the paths that Beethoven had walked, or shopping in the house in which Mozart had written “Don Giovanni”, or going to a movie across the street from where Schubert was born, belonged to the routine experiences of my childhood’.1 As befitting an officer’s son, Krenek received formal musical instruction from a young age, in particular piano lessons and instruction in music theory. The existence of a well-stocked music hire library in the city enabled him to become, by his mid-teens, acquainted with the entire standard Classical and Romantic piano literature of the day. His formal schooling coincidentally introduced Krenek to the literature of classical antiquity and helped ensure that his appreciation of this music would be closely associated in his own mind with his appreciation of western history and classical culture more generally. -

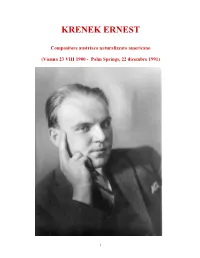

Krenek Ernest

KRENEK ERNEST Compositore austriaco naturalizzato americano (Vienna 23 VIII 1900 - Palm Springs, 22 dicembre 1991) 1 Allievo dal 1916 al 1920 di F. Schreker all'Accademia musicale di Vienna, passò poi alla Hochschule fur Musik di Berlino, dove continuò gli studi con Schreker, ed entrò in proficuo contatto di lavoro con Busoni, A. Schnabel ed altri esponenti del mondo musicale della capitale tedesca. Sposata la figlia di Mahler, Anna (1923) si stabilì in Svizzera ma due anni dopo divorziò e dal 1925 al 1927, su invito di P. Bekker, fu nominato consigliere artistico dell'Opera di Kassel, mettendosi in luce con numerose composizioni teatrali e strumentali ed iniziando un'intensa attività pubblicistica come collaboratore musicale della "Frankfurter Zeitung" e dal 1933 della "Wiener Zeitung”. Ottenuto un successo di portata internazionale con l'opera Jonny spielt auf, dal 1928 si stabilì a Vienna dedicandosi quasi esclusivamente alla composizione, anche qui a contatto con gli ambienti artistici d'avanguardia (Berg, Webern, K. Kraus). Nel 1937 emigrò in America, dove nel 1939 ottenne una cattedra nel Vassar College di Poughkeepsie, presso New York. Dal 1945 ha avuto la cittadinanza americana. Dal 1942 al 1947 ha insegnato nell'Università di Saint Paul, stabilendosi poi a Los Angeles. Dopo la guerra rientrò spesso in Europa, per corsi di composizione, conferenze e concerti. Musicista assai sensibile ai più attuali problemi estetici e di linguaggio, il suo arco creativo rispecchia l'evoluzione spesso contraddittoria delle correnti dell'avanguardia musicale del secolo. L'insegnamento di Schreker lo ha avvicinato nella prima gioventù ad una sorta di espressionismo temperato in senso tardo-romantico, ma ben presto si liberò da quell'influenza per avvicinarsi alle più diverse esperienze musicali. -

Kurt Weill Newsletter Protagonist •T• Zar •T• Santa

KURT WEILL NEWSLETTER Volume 11, Number 1 Spring 1993 IN THI S ISSUE I ssues IN THE GERMAN R ECEPTION OF W EILL 7 Stephen Hinton S PECIAL FEATURE: PROTAGON IST AND Z AR AT SANTA F E 10 Director's Notes by Jonathan Eaton Costume Designs by Robert Perdziola "Der Protagonist: To Be or Not to Be with Der Zar" by Gunther Diehl B OOKS 16 The New Grove Dictionary of Opera Andrew Porter Michael Kater's Different Drummers: Jazz in the Culture of Nazi Germany Susan C. Cook Jilrgen Schebera's Gustav Brecher und die Leipziger Oper 1923-1933 Christopher Hailey PERFORMANCES 19 Britten/Weill Festival in Aldeburgh Patrick O'Connor Seven Deadly Sins at the Los Angeles Philharmonic Paul Young Mahagonny in Karlsruhe Andreas Hauff Knickerbocker Holiday in Evanston. IL bntce d. mcclimg "Nanna's Lied" by the San Francisco Ballet Paul Moor Seven Deadly Sins at the Utah Symphony Bryce Rytting R ECORDINGS 24 Symphonies nos. 1 & 2 on Philips James M. Keller Ofrahs Lieder and other songs on Koch David Hamilton Sieben Stucke aus dem Dreigroschenoper, arr. by Stefan Frenkel on Gallo Pascal Huynh C OLUMNS Letters to the Editor 5 Around the World: A New Beginning in Dessau 6 1993 Grant Awards 4 Above: Georg Kaiser looks down at Weill posing for his picture on the 1928 Leipzig New Publications 15 Opera set for Der Zar /iisst sich pltotographieren, surrounded by the two Angeles: Selected Performances 27 Ilse Koegel 0efl) and Maria Janowska (right). Below: The Czar and His Attendants, costume design for t.he Santa Fe Opera by Robert Perdziola. -

Claudia Maurer Zenck

Claudia Maurer Zenck Publikationsliste A: Bücher Verfolgungsgrund: „Zigeuner“. Unbekannte Musiker und ihr Schicksal im „Dritten Reich“ (= Antifaschistische Literatur und Exilliteratur – Studien und Texte, Bd. 25, hg. v. Verein zur Förderung und Erforschung der antifaschistischen Literatur), Wien: Verlag der Theodor Kramer Gesellschaft, 2016 Mozarts Così fan tutte: dramma giocoso und deutsches Singspiel. Frühe Abschriften und frühe Aufführungen, Schliengen: edition argus, 2007 Vom Takt. Untersuchungen zur Theorie und kompositorischen Praxis im ausgehenden 18. und beginnenden 19. Jahrhundert, Wien / Köln / Weimar: Böhlau, 2001 Ernst Krenek – ein Komponist im Exil, Wien: Lafite, 1980 Versuch über die wahre Art, Debussy zu analysieren (= Berliner musikwissenschaftliche Arbeiten 8), München / Salzburg: Katzbichler, 1974 B: Editionen Ernst Krenek. Frühe Lieder für Gesang und Klavier, 3 Hefte, Wien: Universal Edition, 2015 (mit Einleitung, Textteil, Kritischem Bericht) Ernst Krenek - Briefwechsel mit der Universal Edition (1921-1941), 2 Teile, Köln / Weimar / Wien: Böhlau, 2010 „'...la di Ella inaudita finezza'. Zur Entstehung der Varianti. Briefwechsel Luigi Nono – Rudolf Kolisch 1954–1957/58“, in: Schönberg & Nono. A Birthday Offering to Nuria on May 7, 2002, hg. v. Anna Maria Morazzoni, Florenz: Olschki, 2002, S. 267–315 Ernst Krenek: Die amerikanischen Tagebücher 1937–1942. Dokumente aus dem Exil (Hg. u. Übers.), Wien / Köln / Weimar: Böhlau, 1992 Der hoffnungslose Radikalismus der Mitte. Briefwechsel Ernst Krenek – Friedrich T. Gubler 1928–1939 (Hg.), Wien / Köln: Böhlau, 1989 C: Herausgabe Younghi Pagh-Paan. Auf dem Weg zur musikalischen Symbiose, Mainz: Schott, 2020 (wird im Mai/Juni 2020 erscheinen) (zus. mit Gernot Gruber u. Matthias Schmidt:) Ernst Krenek – nicht nur Komponist (= Ernst Krenek Studien 7), Schliengen: edition argus, 2018 Musik, Bühne und Publikum. -

Download Booklet

Richard Wagner (181 –188) Library The Mastersingers of Nuremberg Photo Music drama in three acts Arts & Libretto by the composer, English translation by Frederick Jameson, Music revised by Norman Feasey and Gordon Kember agner Hans Sachs, cobbler Norman Bailey bass-baritone Lebrecht © Veit Pogner, goldsmith Noel Mangin bass W Kunz Vogelgesang, furrier David Kane tenor Konrad Nachtigal, tinsmith Julian Moyle bass Sixtus Beckmesser, town clerk Derek Hammond-Stroud baritone Fritz Kothner, baker David Bowman bass Balthasar Zorn, pewterer John Brecknock tenor Ulrich Eisslinger, grocer David Morton-Gray tenor Augustin Moser, tailor Mastersingers Dino Pardi tenor Hermann Ortel, soapmaker James Singleton bass CHARD Hans Schwarz, stocking weaver Gerwyn Morgan bass Hans Foltz, coppersmith Eric Stannard bass RI Walther von Stolzing, a young knight from Franconia Alberto Remedios tenor David, Sachs’ apprentice Gregory Dempsey tenor Eva, Pogner’s daughter Margaret Curphey soprano Magdalene, Eva’s nurse Ann Robson mezzo-soprano Nightwatchman Stafford Dean bass Sadler’s Wells Opera Chorus Sadler’s Wells Opera Orchestra Leonard Hancock assistant conductor Reginald Goodall COmpacT DISC ONE Time Page Time Page 1 Prelude 10: �p ��� ��� 11 ‘By silent hearth, one winter’s day’ 9:01 �p 91� Walther, Sachs, Beckmesser, Kothner, Vogelgesang, Nachtigal Act I 12 ‘To make your footsteps safe and sure’ :22 �p 99�� 2 ‘As to thee our Saviour came’ :00 �p ��� ��� Kothner, Walther, Beckmesser Congregation TT 74:34 3 ‘Oh stay! A word! one single word!’ 9:� �p ��� ��� -

Regent Theatre Ulumbarra Theatre, Bendigo

melbourne opera Part One of e Ring of the Nibelung WAGNER’S Regent Theatre Ulumbarra Theatre, Bendigo Principal Sponsor: Henkell Brothers Investment Managers Sponsors: Richard Wagner Society (VIC) • Wagner Society (nsw) Dr Alastair Jackson AM • Lady Potter AC CMRI • Angior Family Foundation Robert Salzer Foundation • Dr Douglas & Mrs Monica Mitchell • Roy Morgan Restart Investment to Sustain and Expand (RISE) Fund melbourneopera.com Classic bistro wine – ethereal, aromatic, textural, sophisticated and so easy to pair with food. They’re wines with poise and charm. Enjoy with friends over a few plates of tapas. debortoli.com.au /DeBortoliWines melbourne opera WAGNER’S COMPOSER & LIBRETTIST RICHARD WAGNER First performed at Munich National Theatre, Munich, Germany on 22nd September 1869. Wotan BASS Eddie Muliaumaseali’i Alberich BARITONE Simon Meadows Loge TENOR James Egglestone Fricka MEZZO-SOPRANO Sarah Sweeting Freia SOPRANO Lee Abrahmsen Froh TENOR Jason Wasley Donner BASS-BARITONE Darcy Carroll Erda MEZZO-SOPRANO Roxane Hislop Mime TENOR Michael Lapina Fasolt BASS Adrian Tamburini Fafner BASS Steven Gallop Woglinde SOPRANO Rebecca Rashleigh Wellgunde SOPRANO Louise Keast Flosshilde MEZZO-SOPRANO Karen Van Spall Conductors Anthony Negus, David Kram FEB 5, 21 Director Suzanne Chaundy Head of Music Raymond Lawrence Set Design Andrew Bailey Video Designer Tobias Edwards Lighting Designer Rob Sowinski Costume Designer Harriet Oxley Set Build & Construction Manager Greg Carroll German Language Diction Coach Carmen Jakobi Company Manager Robbie McPhee Producer Greg Hocking AM MELBOURNE OPERA ORCHESTRA The performance lasts approximately 2 hours 25 minutes with no interval. Principal Sponsor: Henkell Brothers Investment Managers Sponsors: Dr Alastair Jackson AM • Lady Potter AC CMRI • Angior Family Foundation Robert Salzer Foundation • Dr Douglas & Mrs Monica Mitchell • Roy Morgan Restart Investment to Sustain and The role of Loge, performed by James Egglestone, is proudly supported by Expland (RISE) Fund – an Australian the Richard Wagner Society of Victoria. -

6.5 X 11 Double Line.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-87392-5 - Never Sang for Hitler: The Life and Times of Lotte Lehmann, 1888-1976 Michael H. Kater Index More information Index 8 [Acht] Uhr-Blatt, Vienna, 56 Auguste Victoria, ex-queen of Portugal, 137 Abessynians, 273 Auguste Viktoria, Empress, 3, 9 Abravanel, Maurice, 207, 259–61, 287, 298 Austrian Honor Cross First Class, 278 Academy Awards, Hollywood, 232, 236 Austrian Republic, 44, 48, 51, 57, 64–66, 77, Adler, Friedrich, 38 85, 94, 97–99, 166, 307–8 Adolph, Paul, 110–11 Austrian State Theaters, 220 Adventures at the Lido, 234 Austrofascism, 94, 166–69, 308 Agfa company, 185 Aida, 266, 276 Bachur, Max, 15, 18–21, 28, 30–31, 33, Albert Hall, London, 117 42–43 Alceste, 269 Baker, Janet, 251 Alda, Frances, 68 Baker, Josephine, 94 Aldrich, Richard, 69 Baklanoff, Georges, 43 Alexander, king of Yugoslavia, 170 Ballin, Albert, 16, 30, 77, 304 Alice in Wonderland, 193 Balogh, Erno,¨ 147–49, 151, 158, 164, Alien Registration Act, 211 180–81 Allen, Fred, 230 Bampton, Rose, 183, 206, 245 Allen, Judith, 253 Banklin oil refinery, Santa Barbara, 212 Althouse, Paul, 174 Barnard College, Columbia University, New Altmeyer, Jeannine, 261 York, 151 Alvin Theater, New York, 204 Barsewisch, Bernhard von, 1, 13, 35, 285, Alwin, Karl, 102, 106–7, 189, 196 298, 302, 319n172, 343n269 American Committee for Christian German Barsewisch, Elisabeth von, nee´ Gans Edle zu Refugees, 211 Putlitz, 13, 82, 285, 295 American Legion, 68 Bartels, Elise, 11, 14 An die ferne Geliebte, 217 Barthou, Louis, 170 Anderson, Bronco Bill, 198 -

Poetik Und Dramaturgie Der Komischen Operette

9 Romanische Literaturen und Kulturen Albert Gier ‚ Wär es auch nichts als ein Augenblick Poetik und Dramaturgie der komischen Operette ‘ 9 Romanische Literaturen und Kulturen Romanische Literaturen und Kulturen hrsg. von Dina De Rentiies, Albert Gier und Enrique Rodrigues-Moura Band 9 2014 ‚ Wär es auch nichts als ein Augenblick Poetik und Dramaturgie der komischen Operette Albert Gier 2014 Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deut- schen Nationalbibliographie; detaillierte bibliographische Informationen sind im Internet über http://dnb.ddb.de/ abrufbar. Dieses Werk ist als freie Onlineversion über den Hochschulschriften-Server (OPUS; http://www.opus-bayern.de/uni-bamberg/) der Universitätsbibliothek Bamberg erreichbar. Kopien und Ausdrucke dürfen nur zum privaten und sons- tigen eigenen Gebrauch angefertigt werden. Herstellung und Druck: Digital Print Group, Nürnberg Umschlaggestaltung: University of Bamberg Press Titelbild: Johann Strauß, Die Fledermaus, Regie Christof Loy, Bühnenbild und Kostüme Herbert Murauer, Oper Frankfurt (2011). Bild Monika Rittershaus. Abdruck mit freundlicher Genehmigung von Monika Rittershaus (Berlin). © University of Bamberg Press Bamberg 2014 http://www.uni-bamberg.de/ubp/ ISSN: 1867-5042 ISBN: 978-3-86309-258-0 (Druckausgabe) eISBN: 978-3-86309-259-7 (Online-Ausgabe) URN: urn:nbn:de:bvb:473-opus4-106760 Inhalt Einleitung 7 Kapitel I: Eine Gattung wird besichtigt 17 Eigentlichkeit 18; Uneigentliche Eigentlichkeit -

The Concurrent Prevalence of Modernism and Romanticism As Seen in the Operas Performed Between the World Wars and Exemplified in Ernst Krenek’S Jonny Spielt Auf

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 6-10-2020 The Concurrent Prevalence of Modernism and Romanticism as seen in the Operas Performed between the World Wars and Exemplified in Ernst Krenek’s Jonny Spielt Auf Nicole Fassold Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Fassold, Nicole, "The Concurrent Prevalence of Modernism and Romanticism as seen in the Operas Performed between the World Wars and Exemplified in Ernst Krenek’s Jonny Spielt Auf" (2020). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 5301. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/5301 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE CONCURRENT PREVALENCE OF MODERNISM AND ROMANTICISM AS SEEN IN THE OPERAS PERFORMED BETWEEN THE WORLD WARS AND EXEMPLIFIED IN ERNST KRENEK’S JONNY SPIELT AUF A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The College of Music and Dramatic Arts by Nicole Fassold B.M., Colorado State University, 2015 M.M., University of Delaware, 2017 August 2020 Acknowledgements I would like to express my deepest gratitude to the professors and panel members that have guided me throughout my Doctoral studies as well as to my parents and sister, my family all over the world, my friends, and my incredible husband for their unending support and encouragement. -

John Stewart Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8qj7jg3 No online items John Stewart Papers Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Copyright 2013 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla 92093-0175 [email protected] URL: http://libraries.ucsd.edu/collections/sca/index.html John Stewart Papers MSS 0614 1 Descriptive Summary Languages: English Contributing Institution: Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla 92093-0175 Title: John Stewart Papers Identifier/Call Number: MSS 0614 Physical Description: 5.6 Linear feet(15 archives boxes) Date (inclusive): 1916-1991 Abstract: The papers of John Stewart, author, musician and UCSD Muir College provost (1965-1987) contain the research materials for his book about composer Ernst Krenek titled Ernst Krenek: The Man and His Music (1991), including typescript drafts; notes describing correspondence, essays, and articles about Krenek; chronologies; and a series of reel-to-reel audiorecordings of interviews with Krenek by Stewart. Also included are drafts of writings, teaching materials, and correspondence with colleagues including Ernst Krenek. Biography John Lincoln Stewart was born January 24, 1917 in Alton, Illinois, and grew up in Granville and Dwight, Ontario. He graduated from Dennison College with a double major in English and Music and received his doctorate in English literature at Ohio State University. He served in World War II in the Army Signal Corps. He taught English at UCLA and Dartmouth before joining UCSD, publishing The Burden of Time: The Fugitives and Agrarians, a history of the Nashville literary groups of the 1920s and 1930s. Stewart came to UCSD in 1964 to take the lead in establishing arts departments on campus. -

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Polar Music Prize Laureate 2005 Fischer

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Polar Music Prize Laureate 2005 Fischer-Dieskau´s talent for music was manifest at an early age. He took piano lessons and started to study singing in 1941 with Prof. Georg A. Walter. The following year he became a student of Prof. Hermann Weissenborn at the College of Music in Berlin. His first public appearance took place in 1942 at the church hall in Berlin- Zehlendorf, where he sang Schubert´s Winterreise with interruptions for air-raid warnings. After graduating from high school in 1943 he was called up for military service and spent the time until 1947 as a prisoner of war in Italy. There he continued with his singing studies on his own. He resumed his studies with Prof. Weissenborn during the years 1947-48. His real career as a singer began in 1947 when, without prior rehearsal, he substituted for a soloist who had taken ill, in Brahms´ “Ein Deutsches Requiem” in Badenweiler. His official debut as a singer took place in the autumn of 1947 with a song recital in Leipzig, and shortly after that he made a successful appearance at the Titania Palace in Berlin. In the same year he made his first phonograph recording of “Winterreise”. In the autumn of 1948 he was engaged as a lyric baritone at the Städtische Oper in Berlin, where his first appearance, as Posa in Verdi´s opera “Don Carlos” under the baton of Ferenc Fricsay, aroused a great deal of public attention. Then there were guest performances at the opera houses in Vienna and Munich, and from 1951 on also in England, Holland, Switzerland, France and Italy.